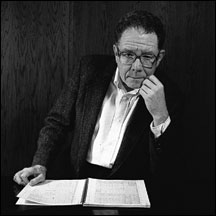

Easley Blackwood

The Composer in Conversation with Bruce Duffie

"The only example there is of that old-fashioned entity known as the composer/pianist." That's how Easley Blackwood describes himself, and it's certainly an apt appraisal.

Born in April of 1933, Blackwood studied with (among others) Olivier Messiaen, Paul Hindemith, and Nadia Boulanger. He spent forty years with the University of Chicago, most as Professor. He is also the pianist with the Chicago Pro Musica - a group otherwise made up entirely of members of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

His compositions began in the typical way for the mid-fifties, but in 1981, he shifted to a tonal style - for which he was praised, ridiculed, and ignored. Fortunately, history will be able to judge his success in both the studious way, and through listening to recordings of his music.

In February of 1993, shortly after the Chicago Symphony gave the world premiere of his Symphony #5, I met with Easley Blackwood at his apartment. Surrounded by scores and other papers, and his kitten, we chatted about a range of ideas.

Easley Blackwood

Bruce Duffie: The first thing I want to do is to check a detail. In a couple of the biographical dictionaries, they mention a 5th symphony from the mid-70s or the late 70s. Is that a mistake?

Easley Blackwood: That's a mistake, yes. There are 4 symphonies. The 4th is from about 1977 I think.

BD: So the 5th is the new one that the Chicago Symphony did just very recently. How did they get an extra symphony in the older books?

EB: I don't know where they found it, but other people have mentioned this to me.

BD: You should write to Slonimsky and a couple of other people and say, "Hey...."

EB: Well, I suppose I should. But I never find time.

BD: I did a show for micro-tonal composer Ezra Sims....

EB: Oh, yeah. I know him.

BD: ...Slonimsky had listed a spurious "String Quartet #2, 1964." So in about 1975, Sims wrote a work for woodwind quartet, but called it "String Quartet #2, 1964," (both laugh) just to make sure that there would be no error in the book!

EB: That's one way of dealing with the problem.

BD: Is it good that your biography and work lists are in readily available reference books?

EB: I don't get any feedback about that. My agent, and the University of course, have material like that and I think that generally, when people need it, it goes through them.

BD: In recent years, you have changed your style of composing. Is this something that happened naturally and gradually, or was this a sudden shift?

EB: Both, I think. It's hard to be sure. The 4th symphony, which is a great big piece for a vastly enlarged orchestra, was a very, very slow proposition to write, and in the middle of that piece, I wrote a violin sonata, as well. Let me try to give a little bit of history. There are several pieces in an idiom that you would call atonal polyrhythmic, including a piece for small chamber ensemble and soprano on a poem of Baudelaire; a trio for piano, violin, and cello; a symphony (#3) for small orchestra; a second violin sonata; a piano concerto. And to a considerable extent, the 4th symphony is in that idiom. In all those pieces, I wasn't interested in simply manipulating random dissonance. I was not interested in serial techniques either. I was trying to give an impression of harmonic motion and texture changes even through an array of sonorities that are not in any identifiable key. I think I began to perceive, perhaps at some unconscious level, after writing for 10 years in this idiom, that it's a dead end. That's not to say that there's anything wrong with it, but after a certain point, it began to lose my interest.

BD: Is it a dead end musically, or just a dead end for your creativity?

EB: I suspect it's a dead end musically. I think that further contribution to that literature is doomed to obscurity.

BD: But it was right that you and others explored it!

EB: Oh yes, that's certainly true. There was a great deal of exploration done in this idiom, not in one exactly like the one that I was using, but in what you'd call atonal polyrythmic texture which starts out shortly after the close of World War II and comes to a big peak with the Darmstadt school, and then gradually begins to fall into a decline somewhere in the middle of the 1960s. By the 70s, it's been, to a large extent, abandoned except by some die-hards, and you find that it was replaced by aleatoric music. Then a little bit later, minimalists come into it. At the same time, when other people were losing interest in it, I was engaged in a big research project about chord progressions within equal tunings where the number of notes is different from 12. What I was particularly interested in was chord progressions that would give a sensation either of modal coherence or else of tonality. That is to say you can actually identify subdominants, dominants, tonics, and keys. In the process of doing that, plus having taught traditional harmony since I came to the University of Chicago in 1958 and writing the microtonal etudes to illustrate these chord progressions, I got, for the first time, firsthand sensation of what it was to write music in tonal idioms. I must say I found that it was rather more amusing than writing in the atonal polyrhythmic idiom that I'd been using.

BD: So is this the purpose of music? To provide amusement for the composer?

EB: Well, I think it is to provide high class entertainment for somebody. That's at least one purpose of it. There are others. I know it's very fashionable these days to indulge in political or social commentary, but if I look at the history of music, I see a vast repertoire where that's not the case at all.

BD: Is the vast repertoire just absolute music?

EB: Just absolute music, or music that was very plainly intended for high class entertainment. I don't think the Mozart Piano Concertos are social or political commentary. I don't think the Beethoven Opus 18 String Quartets are, either.

BD: They're just fun to listen to?

EB: They're just fun to listen to. As I look at music, including those Beethoven quartets that were written during the Napoleonic Wars which go on until 1815, I don't see that, nor in pieces by Schubert written in 1810 or 1812 or 1815. If anything, music was an escape from it. Occasionally, you'd find an opera that had political overtones . . .

BD: . . . Of course, there's a text in those.

EB: There's a text in those but it seems to me if you have an extra-musical message to convey, absolute music is the very worst possible medium because that's the one that's least likely to be understood.

BD: Instead, it has the most possibilities for each individual audience member?

EB: That's right. And it's very vague. A thrilling climax in Mahler is obviously not intended to soothe, and the funeral march movement in Mahler's First is not intended to stimulate the great heights of merriment. This much you can say. But when you get into the subtleties of abstract music, nobody really knows what it means.

BD: When you write a piece of absolute music, are you trying to lead the audience anywhere or are you just providing a forest and letting everyone explore?

EB: I'm trying to put it together in coherent patterns. Without some kind of coherent organization of keys and modulations and form, the piece will become tiresome and incoherent. In any event, after the microtonal etudes, I got an idea that the one that was missing from the set was 12 notes, and I had discovered some chord progressions in 12 notes in the process of looking at some of the other equal tunings, which, oddly enough, were never exploited or used by composers between 1904 and 1915 when they would have been idiomatic. And I thought, well, to write an etude to explore these, obviously, you don't need electronic media. You can just write it for piano. So I wrote a piano piece in that idiom and the piece came out sounding slightly like Scriabin with a little Milhaud perhaps thrown in. Then it occurred to me, "Wait a moment. I can't make do with just one etude. I need a set." So I wrote some more etudes in tonal idiom that sound rather like Russian music in 1905. Then a guitarist approached me and said he'd like a guitar sonata and I had to say, "What kind of an idiom are you interested in? In my judgement, atonal music is not idiomatic on the guitar at all. Would you be interested in a plain, straightforward piece that sounds like something Beethoven might have written in 1820 if he had ever written for the guitar?"

BD: I assume the guitarist jumped at the chance to have you write such a piece.

EB: He said yes. So there came another piece. Shortly after that, a solo violin sonata came out the same way.

BD: So these are all things you were interested in exploring?

EB: Yeah.

BD: Do you feel that musical composition really is exploring?

EB: In a certain sense it is. You're certainly not trying to simply duplicate or paraphrase something that's been done before. I don't see how it's really possible for a composer to do it. Try as you might, you can't help but have your own personal imprint on it. So even a conscious effort to compose in a style of another composer will not entirely succeed, but that doesn't mean that the music you write is going to be devoid of interest or musical worth.

BD: Who decides where the interest is? Is it the composer, is it the historian, is it the audience?

EB: Oh, it's a combination of all the above, and you run into big differences of opinion. There is a faction of people who believe in the inevitability of the acceptance of the so-called academic modern idiom who are very annoyed at what I am doing. They are out and out hostile. They are trying to make me stop. They are trying to demoralize me. I think they are basically intellectually dishonest.

BD: Are they afraid of what you're doing?

EB: I don't think they're afraid of it, but it goes contrary to their notion of historical inevitability. They feel that anyone who departs from the Marxian ideal somehow is not only wrong, but reprehensible. But I think they are intellectually dishonest because I can't help but think that if they didn't know when the piece was written, they would have a different response to it. So these people are not so much trying to evaluate the music or enjoy it, or for that matter, criticize it. They are trying to control the direction of music history.

BD: Then regarding your 5th Symphony, which was just done by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, would you object if it had perhaps come out - even fraudulently for a time - as an unpublished work of a known composer?

EB: No, but that wasn't what I was consciously trying to do. What I was trying to do in that piece was come up with an idiom that I think Sibelius or Vaughan Williams might have discovered if they had experimented with modernism in 1915. I find it much more stimulating and amusing to write in an old-fashioned idiom, a tonal idiom, than a non-tonal idiom. It's much the difference between composing poetry and composing prose. When you write in a tonal idiom, you want it to rhyme and scan. You think about how it comes out in 8 bar phrases or 4 bar phrases or how occasionally, there is a deliberate irregularity in the phrase length to produce a surprise. Certain modulations sound absolutely natural. Others produce surprises. Still others produce bigger surprises. Some produce outright shocks. All of these have their proper place within a context, and in the process of looking at how expert composers manipulate these things, it's hard to say whether they were consciously aware of what they were doing. Certainly, when you look at it in this light, you can see how surprises are deliberately created.

BD: Do you feel that music is a continuum - or perhaps several continuums moving along side each other?

EB: There are periods in music history where there's a surprising unanimity of style and there are other periods where there are 2 distinct styles that are co-existing. There's a surprising unanimity among composers in 1795-1800. Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven tried to flatter the common idiom by writing pieces in it. They each wrote 6 quartets trying to write in the common idiom. I also have the impression that there was unanimity between the classical music and the popular music idioms in 1820 or 1825. As Schubert sat in the coffee houses writing his songs, he was listening to popular music that was in the same idiom. It was just missing the formal intricacy.

BD: Then, where did popular music split off from concert music?

EB: I don't know my music history well enough to pinpoint it, but I can say that at present, it has diverged mightily.

BD: Is that a good thing?

EB: No. I don't think that's good. It was much closer in 1940.

BD: Jazz symphonies, and so on?

EB: Well, the jazz that was written in 1930s and in the ‘40s, really had harmonic intricacies in it. They used change of dominance through the circle of fifths, with complicated altered chords over everyone harmonizing interesting melodies that were in yet another different harmonic mode.

BD: People who listened, though, didn't have to understand that - they just heard it.

EB: They just heard it and it was compelling and expressive. At the same time, orchestral music was being written, and there was a big diversity. Radicals and conservatives were operating practically from 1910 until certainly 1960, and apparently conservatives were operating all through the 60s and 70s but being largely ignored.

BD: The Menotti types?

EB: Or the Walter Piston types or Roy Harris types or Vaughan Williams types.

BD: I only bring up Menotti because it just seemed like he would write things that nobody liked - except the public!

EB: Yes, that's true.

BD: And he was always maligned by the critics.

EB: Yes, he was. Well, not all the critics, but take Edward Rothstein as an example. He is certainly of the opinion that if the public likes it, it must be no good. For him, music must be post-Schoenberg, it must be post-Webern. He must see some kind of Hegelian sense of support there and thinks that at long last, when the tyranny of harmony is liberated, music will then live in some kind of a bucolic utopia.

BD: Is he confusing music with politics?

EB: I think he's proceeding from some kind of a Marxian ideal which gives rise to this same false political theory.