November 20, 2017.Penderecki. Krzysztof Penderecki, one of the best known Polish composers of the 20th century, was born on November 23rd of 1933 in the small town of Dębica in southeastern Poland.The town’s name in Yiddish was Dembitz, and before WWII the majority of the population was Jewish – later, Penderecki would use Jewish music in several compositions.In addition to Polish, Penderecki’s family had Armenian and German roots.The family wasn’t musical, but, as was customary in educated families of the time, Krzysztof took piano lessons.Somebody presented Krzysztof’s father with a violin, and the boy took a liking to the instrument.In 1951 Penderecki moved to Krakow, attending Jagiellonian University first, and then transferring to the Academy of Music.There he studied the violin for one year, but then switched completely to composition.He graduated in 1958 and one year later received three awards for three compositions he submitted to the young composers’ competition, organized by the Polish Composers’ Union.His Strofy (‘Strophes’) received the first prize, and Emanacje (‘Emanations’) and Psalmy Dawida (‘Psalms of David’) shared the second.All compositions were submitted anonymously, and the jury didn’t know that all winning entries were written by the same composer.Since 1956, when Poland opened up after years of Stalinism, cultural life became less controlled.While still a Communist state, culturally Poland was the freest country in the Soviet bloc.New music could be performed, and music of young composers could be heard in the West.One person who became familiar with Penderecki’s work was Heinrich Strobel, principal of the Music Department of the Südwestrundfunk (SWR) Symphony Orchestra of Baden-Baden, one of the leading new Music ensembles.Strobel, a champion of Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen, became a promoter of the works of Krzysztof Penderecki.In 1960, Penderecki’s popularity in the West lead to an interesting episode.He had just completed a piece he initially called 8’37”, for the exact performing duration of the composition, which he later renamed Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima.

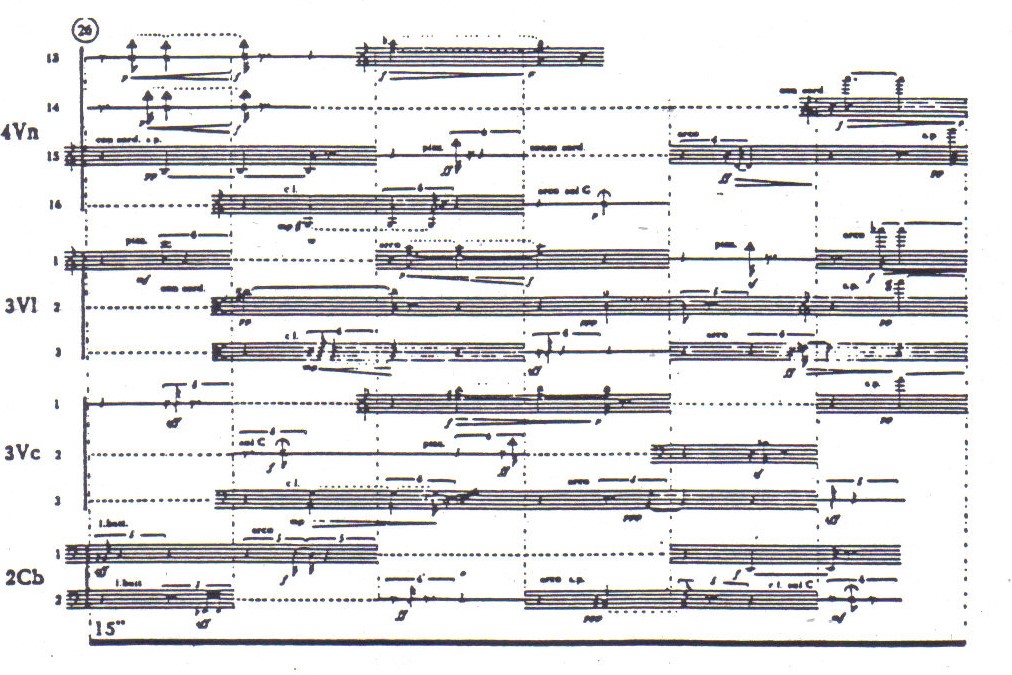

The piece, scored for 52 string instruments, required unorthodox performing technique, like unusual glissandos, playing on the tailpiece, etc.This, in turn, required unconventional notation, which Penderecki invented himself.The notation created many problems, as musicians couldn’t figure out what was required of them; Penderecki had to work with the orchestras to explain his intent (you can see a small excerpt on the right).When several European ensembles decided to perform Trenody, Penderecki sent the score to his German publisher.The package never arrived, apparently it got lost in the mail, and Penderecki had to recreate it from memory.Sometime later the score reappeared and was delivered то the addressee.When the two versions were compared, it turned out that they were identical.This provides wonderful proof of the exactness of Penderecki’s intent, the music of necessity of every note despite the seeming chaos of the twelve-tone composition.But the story doesn’t end there.Later, the reason for the score’s long delay was discovered: the custom officials who examined the unusual notation decided that it couldn’t have been music; they suspected that it was a document containing some encoded secret information, probably of military or political significance.Only after a lengthy examination did they discover that this indeed was a music score and sent it to the publisher.Here’s Trenody in the performance by the National Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Antoni Wit conducting.

Around 1975 Penderecki’s style, which up to then had been very much modernist, underwent a considerable change and became more melodic, in a neo-romantic way.So different is his music written in the second half of his career that we’ll have to address it separately.

Krzysztof Penderecki, 2017

November 20, 2017. Penderecki. Krzysztof Penderecki, one of the best known Polish composers of the 20th century, was born on November 23rd of 1933 in the small town of Dębica in southeastern Poland. The town’s name in Yiddish was Dembitz, and before WWII the majority of the population was Jewish – later, Penderecki would use Jewish music in several compositions. In addition to Polish, Penderecki’s family had Armenian and German roots. The family wasn’t musical, but, as was customary in educated families of the time, Krzysztof took piano lessons. Somebody presented Krzysztof’s father with a violin, and the boy took a liking to the instrument. In 1951 Penderecki moved to Krakow, attending Jagiellonian University first, and then transferring to the Academy of Music. There he studied the violin for one year, but then switched completely to composition. He graduated in 1958 and one year later received three awards for three compositions he submitted to the young composers’ competition, organized by the Polish Composers’ Union. His Strofy (‘Strophes’) received the first prize, and Emanacje (‘Emanations’) and Psalmy Dawida (‘Psalms of David’) shared the second. All compositions were submitted anonymously, and the jury didn’t know that all winning entries were written by the same composer. Since 1956, when Poland opened up after years of Stalinism, cultural life became less controlled. While still a Communist state, culturally Poland was the freest country in the Soviet bloc. New music could be performed, and music of young composers could be heard in the West. One person who became familiar with Penderecki’s work was Heinrich Strobel, principal of the Music Department of the Südwestrundfunk (SWR) Symphony Orchestra of Baden-Baden, one of the leading new Music ensembles. Strobel, a champion of Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen, became a promoter of the works of Krzysztof Penderecki. In 1960, Penderecki’s popularity in the West lead to an interesting episode. He had just completed a piece he initially called 8’37”, for the exact performing duration of the composition, which he later renamed Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima.

Penderecki’s family had Armenian and German roots. The family wasn’t musical, but, as was customary in educated families of the time, Krzysztof took piano lessons. Somebody presented Krzysztof’s father with a violin, and the boy took a liking to the instrument. In 1951 Penderecki moved to Krakow, attending Jagiellonian University first, and then transferring to the Academy of Music. There he studied the violin for one year, but then switched completely to composition. He graduated in 1958 and one year later received three awards for three compositions he submitted to the young composers’ competition, organized by the Polish Composers’ Union. His Strofy (‘Strophes’) received the first prize, and Emanacje (‘Emanations’) and Psalmy Dawida (‘Psalms of David’) shared the second. All compositions were submitted anonymously, and the jury didn’t know that all winning entries were written by the same composer. Since 1956, when Poland opened up after years of Stalinism, cultural life became less controlled. While still a Communist state, culturally Poland was the freest country in the Soviet bloc. New music could be performed, and music of young composers could be heard in the West. One person who became familiar with Penderecki’s work was Heinrich Strobel, principal of the Music Department of the Südwestrundfunk (SWR) Symphony Orchestra of Baden-Baden, one of the leading new Music ensembles. Strobel, a champion of Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen, became a promoter of the works of Krzysztof Penderecki. In 1960, Penderecki’s popularity in the West lead to an interesting episode. He had just completed a piece he initially called 8’37”, for the exact performing duration of the composition, which he later renamed Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima.

The piece, scored for 52 string instruments, required unorthodox performing technique, like unusual glissandos, playing on the tailpiece, etc. This, in turn, required unconventional notation, which Penderecki invented himself. The notation created many problems, as musicians couldn’t figure out what was required of them; Penderecki had to work with the orchestras to explain his intent (you can see a small excerpt on the right). When several European ensembles decided to perform Trenody, Penderecki sent the score to his German publisher. The package never arrived, apparently it got lost in the mail, and Penderecki had to recreate it from memory. Sometime later the score reappeared and was delivered то the addressee. When the two versions were compared, it turned out that they were identical. This provides wonderful proof of the exactness of Penderecki’s intent, the music of necessity of every note despite the seeming chaos of the twelve-tone composition. But the story doesn’t end there. Later, the reason for the score’s long delay was discovered: the custom officials who examined the unusual notation decided that it couldn’t have been music; they suspected that it was a document containing some encoded secret information, probably of military or political significance. Only after a lengthy examination did they discover that this indeed was a music score and sent it to the publisher. Here’s Trenody in the performance by the National Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Antoni Wit conducting.

himself. The notation created many problems, as musicians couldn’t figure out what was required of them; Penderecki had to work with the orchestras to explain his intent (you can see a small excerpt on the right). When several European ensembles decided to perform Trenody, Penderecki sent the score to his German publisher. The package never arrived, apparently it got lost in the mail, and Penderecki had to recreate it from memory. Sometime later the score reappeared and was delivered то the addressee. When the two versions were compared, it turned out that they were identical. This provides wonderful proof of the exactness of Penderecki’s intent, the music of necessity of every note despite the seeming chaos of the twelve-tone composition. But the story doesn’t end there. Later, the reason for the score’s long delay was discovered: the custom officials who examined the unusual notation decided that it couldn’t have been music; they suspected that it was a document containing some encoded secret information, probably of military or political significance. Only after a lengthy examination did they discover that this indeed was a music score and sent it to the publisher. Here’s Trenody in the performance by the National Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Antoni Wit conducting.

Around 1975 Penderecki’s style, which up to then had been very much modernist, underwent a considerable change and became more melodic, in a neo-romantic way. So different is his music written in the second half of his career that we’ll have to address it separately.