This Week in Classical Music: February 27, 2023.A mystery composer.Whom do you write about when you have Frédéric Chopin,Antonio Vivaldi, Gioachino Rossini, Bedřich Smetana, and Kurt Weill among the composers born this week, plus the pianist Issay Dobrowen, the violinist Gidon Kremer, the soprano Mirella Freni, and the conductor Bernard Haitink?The obvious answer is, you write about Sergei Bortkiewicz.Yes, we’re being facetious, but we’ve written about Chopin, Vivaldi, and Rossini many times (we haven’t had a chance to write about Dobrowen yet, a very interesting figure).Bortkiewicz, on the other hand, is a composer we knew only by name until recently when we heard his Symphony no. 1 and thought it was something from the late 19th century, maybe a very early Rachmaninov – but no, it turned out to be a piece composed in 1940.While conservatism is not the most admirable feature, Bortkiewicz is not alone in that regard: the above-mentioned Rachmaninov was also not the most adventuresome composer.Neither was Rimsky-Korsakov, not even Tchaikovsky, which didn’t preclude both of them from writing very interesting (and popular) music.Richard Strauss, for all his talent, was a follower of the Romantic tradition.Even Johann Sebastian Bach in his later years was well behind the prevailing trends of his time.Listen, for example, to two pieces written at about the same time: 1741-1742, Johann Sebastian’s wonderful, if somewhat archaic, Cantata Bekennen will ich seinen Namen BWV 200 (here), and then C.P.E.’s Symphony in G major, Wq. 173, written in the then “modern” style (here).They belong to different eras, even if the cantata is much better.We admire and love the pioneers like Mahler, Schoenberg, and Stravinsky, but as important as they are, there is a lot of space in the musical universe for the less daring composers.We’re not comparing the talent of Sergei Bortkiewicz with that of the “conservatives” mentioned above, but some of his music is pleasant and his life story is interesting.

Sergei Bortkiewicz was born in Kharkiv on February 28th of 1877.Back then Kharkiv was part of the Russian Empire; now it is a city in Ukraine being constantly attacked by Putin’s Russian army.He studied music first in his hometown, then in St.-Petersburg, where one of his teachers was Anatoly Lyadov.In 1900 he entered the Leipzig Conservatory, where he studied piano and composition for two years.From 1904 to 1914 he lived in Berlin.While there he wrote a very successful Piano Concerto no. 1.At the outbreak of WWI, he, as a Russian citizen and therefore an enemy, was deported from Germany.Bortkiewicz settled temporarily in St.-Petersburg and then moved back to Kharkiv.After the October Revolution, amid the chaos of the Civil War, he emigrated to Constantinople and then, in 1922, to Vienna, where he lived for the rest of his life (he died there in 1952).In 1930 he wrote his Piano Concerto no. 2 for the left hand; it was one of the pieces commissioned by Paul Wittgenstein, the pianist who lost his right hand during the Great War.Altogether Bortkiewicz composed three piano concertos, two symphonies, an opera and several other symphonic and chamber pieces, all in the late-Romantic Russian style.It was as if the music of the 20th century hadn’t existed.

Here's Bortkiewicz Piano Concerto no. 1.It’s performed by Ukrainian musicians: Olga Shadrina is at the piano; Mykola Sukach is conducting the Odessa Philharmonic Orchestra.

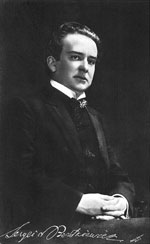

Bortkiewicz, 2023

This Week in Classical Music: February 27, 2023. A mystery composer. Whom do you write about when you have Frédéric Chopin, Antonio Vivaldi, Gioachino Rossini, Bedřich Smetana, and Kurt Weill among the composers born this week, plus the pianist Issay Dobrowen, the violinist Gidon Kremer, the soprano Mirella Freni, and the conductor Bernard Haitink? The obvious answer is, you write about Sergei Bortkiewicz. Yes, we’re being facetious, but we’ve written about Chopin, Vivaldi, and Rossini many times (we haven’t had a chance to write about Dobrowen yet, a very interesting figure). Bortkiewicz, on the other hand, is a composer we knew only by name until recently when we heard his Symphony no. 1 and thought it was something from the late 19th century, maybe a very early Rachmaninov – but no, it turned out to be a piece composed in 1940. While conservatism is not the most admirable feature, Bortkiewicz is not alone in that regard: the above-mentioned Rachmaninov was also not the most adventuresome composer. Neither was Rimsky-Korsakov, not even Tchaikovsky, which didn’t preclude both of them from writing very interesting (and popular) music. Richard Strauss, for all his talent, was a follower of the Romantic tradition. Even Johann Sebastian Bach in his later years was well behind the prevailing trends of his time. Listen, for example, to two pieces written at about the same time: 1741-1742, Johann Sebastian’s wonderful, if somewhat archaic, Cantata Bekennen will ich seinen Namen BWV 200 (here), and then C.P.E.’s Symphony in G major, Wq. 173, written in the then “modern” style (here). They belong to different eras, even if the cantata is much better. We admire and love the pioneers like Mahler, Schoenberg, and Stravinsky, but as important as they are, there is a lot of space in the musical universe for the less daring composers. We’re not comparing the talent of Sergei Bortkiewicz with that of the “conservatives” mentioned above, but some of his music is pleasant and his life story is interesting.

and Kurt Weill among the composers born this week, plus the pianist Issay Dobrowen, the violinist Gidon Kremer, the soprano Mirella Freni, and the conductor Bernard Haitink? The obvious answer is, you write about Sergei Bortkiewicz. Yes, we’re being facetious, but we’ve written about Chopin, Vivaldi, and Rossini many times (we haven’t had a chance to write about Dobrowen yet, a very interesting figure). Bortkiewicz, on the other hand, is a composer we knew only by name until recently when we heard his Symphony no. 1 and thought it was something from the late 19th century, maybe a very early Rachmaninov – but no, it turned out to be a piece composed in 1940. While conservatism is not the most admirable feature, Bortkiewicz is not alone in that regard: the above-mentioned Rachmaninov was also not the most adventuresome composer. Neither was Rimsky-Korsakov, not even Tchaikovsky, which didn’t preclude both of them from writing very interesting (and popular) music. Richard Strauss, for all his talent, was a follower of the Romantic tradition. Even Johann Sebastian Bach in his later years was well behind the prevailing trends of his time. Listen, for example, to two pieces written at about the same time: 1741-1742, Johann Sebastian’s wonderful, if somewhat archaic, Cantata Bekennen will ich seinen Namen BWV 200 (here), and then C.P.E.’s Symphony in G major, Wq. 173, written in the then “modern” style (here). They belong to different eras, even if the cantata is much better. We admire and love the pioneers like Mahler, Schoenberg, and Stravinsky, but as important as they are, there is a lot of space in the musical universe for the less daring composers. We’re not comparing the talent of Sergei Bortkiewicz with that of the “conservatives” mentioned above, but some of his music is pleasant and his life story is interesting.

Sergei Bortkiewicz was born in Kharkiv on February 28th of 1877. Back then Kharkiv was part of the Russian Empire; now it is a city in Ukraine being constantly attacked by Putin’s Russian army. He studied music first in his hometown, then in St.-Petersburg, where one of his teachers was Anatoly Lyadov. In 1900 he entered the Leipzig Conservatory, where he studied piano and composition for two years. From 1904 to 1914 he lived in Berlin. While there he wrote a very successful Piano Concerto no. 1. At the outbreak of WWI, he, as a Russian citizen and therefore an enemy, was deported from Germany. Bortkiewicz settled temporarily in St.-Petersburg and then moved back to Kharkiv. After the October Revolution, amid the chaos of the Civil War, he emigrated to Constantinople and then, in 1922, to Vienna, where he lived for the rest of his life (he died there in 1952). In 1930 he wrote his Piano Concerto no. 2 for the left hand; it was one of the pieces commissioned by Paul Wittgenstein, the pianist who lost his right hand during the Great War. Altogether Bortkiewicz composed three piano concertos, two symphonies, an opera and several other symphonic and chamber pieces, all in the late-Romantic Russian style. It was as if the music of the 20th century hadn’t existed.

Here's Bortkiewicz Piano Concerto no. 1. It’s performed by Ukrainian musicians: Olga Shadrina is at the piano; Mykola Sukach is conducting the Odessa Philharmonic Orchestra.