This Week in Classical Music: September 25, 2023.Florent Schmitt. We have to admit that we’re fascinated with the “bad boys” of music.They are invariably “boys,” as there are no “bad girls” in music historiography that we’re aware of.As for the male composers, there are plenty, Richard Wagner being the quintessential one.In the last couple of years, we’ve written about several of them, mostly the Germans in the 20th century, even though they are not the only ones: there were plenty of baddies in the Soviet bloc and, in a very different way, several Italians of the Renaissance.This week it’s Florent Schmitt’s turn, a French composer infamous for shouting “Vive Hitler!” during a concert.(Dmitri Shostakovich was also born this week, and, as talented as he was, he was no angel either, but we’ll return to Shostakovich another time).Schmitt was born on September 28th of 1870 in the town of Meurthe-et-Moselle, Lorraine, the area that was passing from France to Germany and back for centuries – thus the German name.At 17, he entered the conservatory in nearby Nancy, and two years later moved to Paris where he studied composition with Gabriel Fauré and Jules Massenet.While in Paris, Schmitt became friends with Frederick Delius, the English composer of German descent who was then living in Paris.In the 1890s he befriended Ravel and met Debussy.

Schmitt tried to get the prestigious Prix de Rome five times, submitting five different compositions every year from 1896 to 1900, when he finally won it with the cantata Sémiramis.He spent three years in Rome and then traveled extensively, visiting Russia and North Africa, among other places.One of his most popular pieces composed during the period after Rome is the Piano Quintet op. 51 (1902-1908).Schmitt dedicated it to Fauré.Here’s the final movement, Animé, performed by the Stanislas Quartet with Christian Ivaldi at the piano.The ballet La tragédie de Salomé was composed during the same period, in 1907.Igor Stravinsky was taken by it; in Grove’s quote, he wrote to Schmitt: “I am only playing French music – yours, Debussy, Ravel’.And later, “I confess that [Salomé] has given me greater joy than any work I have heard in a long time.”In 1910 Schmitt created a concert version of the ballet.Here’s the second part of it (the New Philharmonia Orchestra is conducted by Antonio de Almeida).It’s not surprising that Stravinsky liked it, as it clearly presages parts of Rite of Spring.Another important piece, Psalm XLVII, was written in 1906.

During WWI Schmitt wrote music for military bands but returned to regular composing once the war was over.He also worked as a music critic for the newspaper Le Temps.Schmitt was a nationalist with pronounced sympathies toward the Nazi regime.The episode we referred to at the beginning of this entry happened in November of 1933.During a concert of the music of Kurt Weill, a Jewish composer who had beenrecently forced into exile by the Nazis, he stood up and shouted “Vive Hitler!”According to a witness, he added: “We already have enough bad musicians to have to welcome German Jews.”That makes him not only a Nazi sympathizer but also an antisemite.During the German occupation of France, Schmitt collaborated with the Vichy government and was a member of the Music section of the France-Germany Committee. He visited Germany and in December of 1941 went to Vienna to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Mozart’s death.After the liberation, Schmitt was investigated as a collaborator, but these proceedings were later dropped, although a year-long ban was imposed on performing and publishing his music.Soon after everything was forgotten and in 1952, just seven years after the end of the war, Schmitt was made the Commander of the Legion of Honor.In 1996, the controversial past of this "one of the most fascinating of France's lesser-known classical composers," as he’s often described, came into prominence again, and his name was removed from a school and a concert hall.

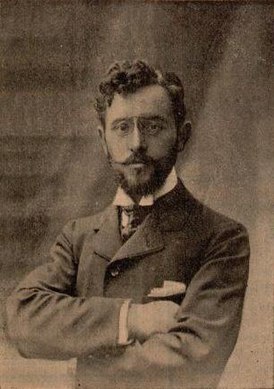

Florent Schmitt, 2023

This Week in Classical Music: September 25, 2023. Florent Schmitt. We have to admit that we’re fascinated with the “bad boys” of music. They are invariably “boys,” as there are no “bad girls” in music historiography that we’re aware of. As for the male composers, there are plenty, Richard Wagner being the quintessential one. In the last couple of years, we’ve written about several of them, mostly the Germans in the 20th century, even though they are not the only ones: there were plenty of baddies in the Soviet bloc and, in a very different way, several Italians of the Renaissance. This week it’s Florent Schmitt’s turn, a French composer infamous for shouting “Vive Hitler!” during a concert. (Dmitri Shostakovich was also born this week, and, as talented as he was, he was no angel either, but we’ll return to Shostakovich another time). Schmitt was born on September 28th of 1870 in the town of Meurthe-et-Moselle, Lorraine, the area that was passing from France to Germany and back for centuries – thus the German name. At 17, he entered the conservatory in nearby Nancy, and two years later moved to Paris where he studied composition with Gabriel Fauré and Jules Massenet. While in Paris, Schmitt became friends with Frederick Delius, the English composer of German descent who was then living in Paris. In the 1890s he befriended Ravel and met Debussy.

girls” in music historiography that we’re aware of. As for the male composers, there are plenty, Richard Wagner being the quintessential one. In the last couple of years, we’ve written about several of them, mostly the Germans in the 20th century, even though they are not the only ones: there were plenty of baddies in the Soviet bloc and, in a very different way, several Italians of the Renaissance. This week it’s Florent Schmitt’s turn, a French composer infamous for shouting “Vive Hitler!” during a concert. (Dmitri Shostakovich was also born this week, and, as talented as he was, he was no angel either, but we’ll return to Shostakovich another time). Schmitt was born on September 28th of 1870 in the town of Meurthe-et-Moselle, Lorraine, the area that was passing from France to Germany and back for centuries – thus the German name. At 17, he entered the conservatory in nearby Nancy, and two years later moved to Paris where he studied composition with Gabriel Fauré and Jules Massenet. While in Paris, Schmitt became friends with Frederick Delius, the English composer of German descent who was then living in Paris. In the 1890s he befriended Ravel and met Debussy.

Schmitt tried to get the prestigious Prix de Rome five times, submitting five different compositions every year from 1896 to 1900, when he finally won it with the cantata Sémiramis. He spent three years in Rome and then traveled extensively, visiting Russia and North Africa, among other places. One of his most popular pieces composed during the period after Rome is the Piano Quintet op. 51 (1902-1908). Schmitt dedicated it to Fauré. Here’s the final movement, Animé, performed by the Stanislas Quartet with Christian Ivaldi at the piano. The ballet La tragédie de Salomé was composed during the same period, in 1907. Igor Stravinsky was taken by it; in Grove’s quote, he wrote to Schmitt: “I am only playing French music – yours, Debussy, Ravel’. And later, “I confess that [Salomé] has given me greater joy than any work I have heard in a long time.” In 1910 Schmitt created a concert version of the ballet. Here’s the second part of it (the New Philharmonia Orchestra is conducted by Antonio de Almeida). It’s not surprising that Stravinsky liked it, as it clearly presages parts of Rite of Spring. Another important piece, Psalm XLVII, was written in 1906.

During WWI Schmitt wrote music for military bands but returned to regular composing once the war was over. He also worked as a music critic for the newspaper Le Temps. Schmitt was a nationalist with pronounced sympathies toward the Nazi regime. The episode we referred to at the beginning of this entry happened in November of 1933. During a concert of the music of Kurt Weill, a Jewish composer who had beenrecently forced into exile by the Nazis, he stood up and shouted “Vive Hitler!” According to a witness, he added: “We already have enough bad musicians to have to welcome German Jews.” That makes him not only a Nazi sympathizer but also an antisemite. During the German occupation of France, Schmitt collaborated with the Vichy government and was a member of the Music section of the France-Germany Committee. He visited Germany and in December of 1941 went to Vienna to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Mozart’s death. After the liberation, Schmitt was investigated as a collaborator, but these proceedings were later dropped, although a year-long ban was imposed on performing and publishing his music. Soon after everything was forgotten and in 1952, just seven years after the end of the war, Schmitt was made the Commander of the Legion of Honor. In 1996, the controversial past of this "one of the most fascinating of France's lesser-known classical composers," as he’s often described, came into prominence again, and his name was removed from a school and a concert hall.