This Week in Classical Music: July 8, 2024. Mahler, Eisler.Last week, we wanted to write about Hanns Eisler who was born on July 7th but were sidelined by the 100th anniversary of the great cellist János Starker.July 7th was also the anniversary of Gustav Mahler, and we couldn’t miss it.Mahler was born in 1860; his last completed symphony, no. 9, was written between 1908 and 1909 (he died in 1911, at age 50).The last (fourth), movement of the symphony, Adagio, is one of the greatest pieces of music ever written, bar none.The movement preceding it, Rondo-Burleske, is denoted by Mahler as Allegro assai (Very cheerful) and Sehr trotzig (Very defiant).It’s complex, contrapuntal, and borderline insane, and not cheerful at all.It’s difficult for a conductor to interpret and for an orchestra to play.At the same time, if well done, it leads perfectly into the deathly serenity of the last movement.Here is Claudio Abbado with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra in a live 2010 performance.You can compare it with the interpretation by Pierre Boulez and Chicago, here.

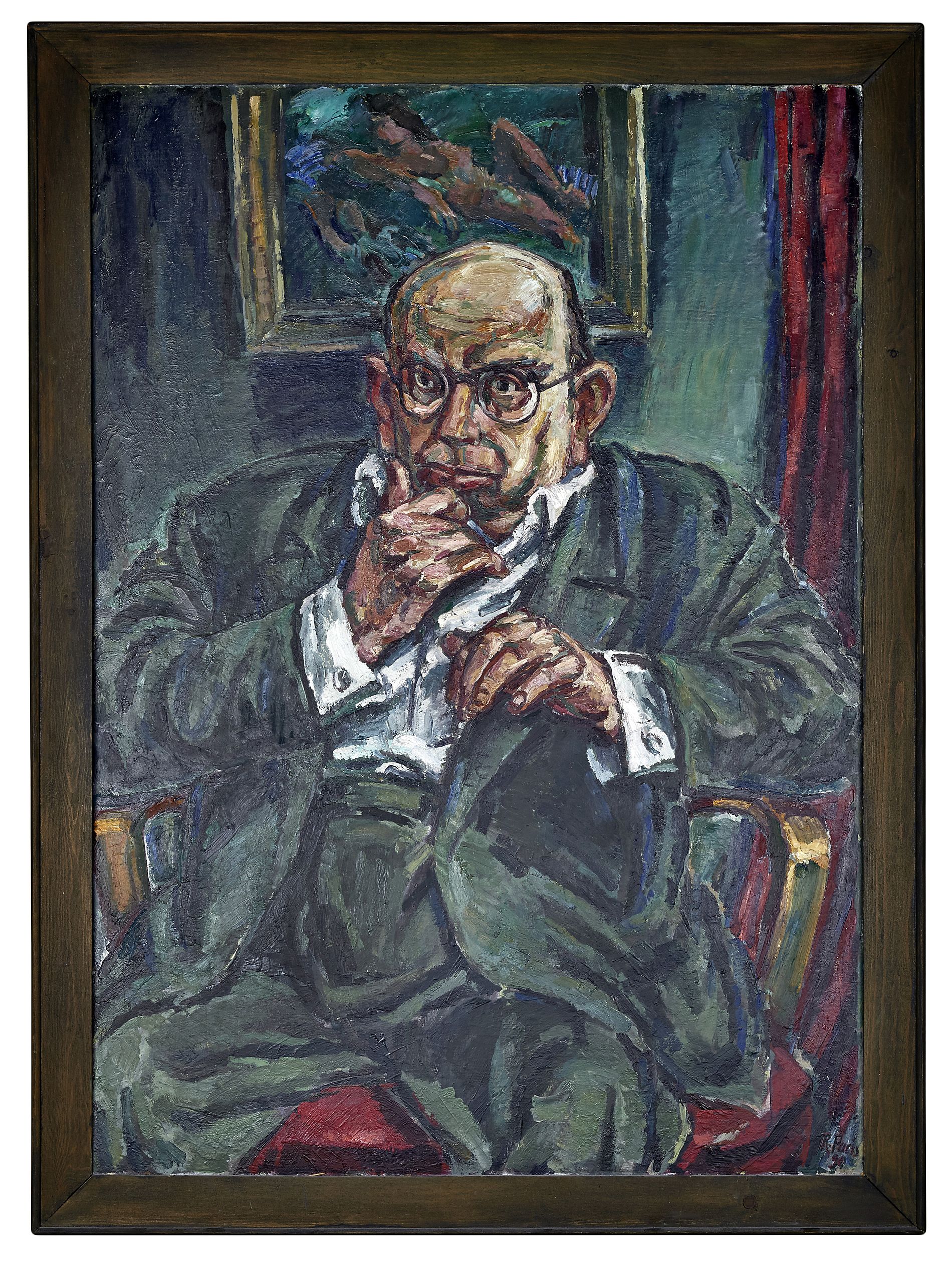

Now back to Hanns Eisler.Eisler was born in Leipzig, Germany, on July 7th of 1898; his father was Jewish, his mother Lutheran.The family was very political: Hanns’s brother was a prominent communist journalist, while his sister, Elfriede Eisler-Fischer, was a co-founder of the Austrian Communist party.In 1901 the family moved to Vienna.Hanns himself became active in politics at the age of 14, joining a Socialist youth group.During the Great War, Eisler served in the Austrian army.As a boy, he studied the piano on and off and composed some music (he did it even during the war).In 1918 the war was lost, the Austro-Hungarian empire disappeared; Eisler returned to the impoverished Vienna, now the capital of a tiny Austria, looking to continue his musical studies.He was accepted by Arnold Schoenberg, who taught him composition free of charge (Anton Webern sometimes was the substitute teacher).Inculcated in atonality and serialism, Eisler wrote several pieces that sounded very much like his teacher’s, especially the ones written for voice.Here, for example, is Palmström for Voice, Flute, Clarinet, Violin, Viola and Cello, which Schoenberg asked Eisler to write for a performance that also featured Pierrot lunaire (Junko Ohtsu- Bormann is the soprano).Eisler’s piano pieces of the period were light and fresh, as, for example, is the short Andante con moto, op. 3, no.1 (Siegfried Stöckigt is the pianist).

Parallel to being involved with music, Eisler continued to be actively engaged in politics, and that, in turn, strongly affected his composition style.Eisler became a devoted Marxist and joined several radical leftist organizations, first in Austria and then, after moving to Germany in 1925, in Berlin where he applied for membership in the German Communist Party.He became disaffected with the “bourgeois” 12-tonal music and quarreled with Schoenberg who could not accept his student’s political views.Affected by ideology, Eisler switched to composing marches and solidarity songs, including Kominternlied, the unofficial hymn of the Comintern, the Soviet Union-led Communist International.Many of his songs became very popular with the European Left.They contained fighting words, and we should remember that that was the time when the Communists were literally fighting the Nazis on the streets of Germany.

In 1930 Eisler met the playwright Bertolt Brecht, one of the stars of the Left.They became lifelong friends and their cooperation led to several influential theatrical productions.We’ll finish the story of Hans Eisler during the Nazi period, his emigration and, later, his unexpected return to Germany, next week.

Mahler, Eisler, 2024

This Week in Classical Music: July 8, 2024. Mahler, Eisler. Last week, we wanted to write about Hanns Eisler who was born on July 7th but were sidelined by the 100th anniversary of the great cellist János Starker. July 7th was also the anniversary of Gustav Mahler, and we couldn’t miss it. Mahler was born in 1860; his last completed symphony, no. 9, was written between 1908 and 1909 (he died in 1911, at age 50). The last (fourth), movement of the symphony, Adagio, is one of the greatest pieces of music ever written, bar none. The movement preceding it, Rondo-Burleske, is denoted by Mahler as Allegro assai (Very cheerful) and Sehr trotzig (Very defiant). It’s complex, contrapuntal, and borderline insane, and not cheerful at all. It’s difficult for a conductor to interpret and for an orchestra to play. At the same time, if well done, it leads perfectly into the deathly serenity of the last movement. Here is Claudio Abbado with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra in a live 2010 performance. You can compare it with the interpretation by Pierre Boulez and Chicago, here.

great cellist János Starker. July 7th was also the anniversary of Gustav Mahler, and we couldn’t miss it. Mahler was born in 1860; his last completed symphony, no. 9, was written between 1908 and 1909 (he died in 1911, at age 50). The last (fourth), movement of the symphony, Adagio, is one of the greatest pieces of music ever written, bar none. The movement preceding it, Rondo-Burleske, is denoted by Mahler as Allegro assai (Very cheerful) and Sehr trotzig (Very defiant). It’s complex, contrapuntal, and borderline insane, and not cheerful at all. It’s difficult for a conductor to interpret and for an orchestra to play. At the same time, if well done, it leads perfectly into the deathly serenity of the last movement. Here is Claudio Abbado with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra in a live 2010 performance. You can compare it with the interpretation by Pierre Boulez and Chicago, here.

Now back to Hanns Eisler. Eisler was born in Leipzig, Germany, on July 7th of 1898; his father was Jewish, his mother Lutheran. The family was very political: Hanns’s brother was a prominent communist journalist, while his sister, Elfriede Eisler-Fischer, was a co-founder of the Austrian Communist party. In 1901 the family moved to Vienna. Hanns himself became active in politics at the age of 14, joining a Socialist youth group. During the Great War, Eisler served in the Austrian army. As a boy, he studied the piano on and off and composed some music (he did it even during the war). In 1918 the war was lost, the Austro-Hungarian empire disappeared; Eisler returned to the impoverished Vienna, now the capital of a tiny Austria, looking to continue his musical studies. He was accepted by Arnold Schoenberg, who taught him composition free of charge (Anton Webern sometimes was the substitute teacher). Inculcated in atonality and serialism, Eisler wrote several pieces that sounded very much like his teacher’s, especially the ones written for voice. Here, for example, is Palmström for Voice, Flute, Clarinet, Violin, Viola and Cello, which Schoenberg asked Eisler to write for a performance that also featured Pierrot lunaire (Junko Ohtsu- Bormann is the soprano). Eisler’s piano pieces of the period were light and fresh, as, for example, is the short Andante con moto, op. 3, no.1 (Siegfried Stöckigt is the pianist).

father was Jewish, his mother Lutheran. The family was very political: Hanns’s brother was a prominent communist journalist, while his sister, Elfriede Eisler-Fischer, was a co-founder of the Austrian Communist party. In 1901 the family moved to Vienna. Hanns himself became active in politics at the age of 14, joining a Socialist youth group. During the Great War, Eisler served in the Austrian army. As a boy, he studied the piano on and off and composed some music (he did it even during the war). In 1918 the war was lost, the Austro-Hungarian empire disappeared; Eisler returned to the impoverished Vienna, now the capital of a tiny Austria, looking to continue his musical studies. He was accepted by Arnold Schoenberg, who taught him composition free of charge (Anton Webern sometimes was the substitute teacher). Inculcated in atonality and serialism, Eisler wrote several pieces that sounded very much like his teacher’s, especially the ones written for voice. Here, for example, is Palmström for Voice, Flute, Clarinet, Violin, Viola and Cello, which Schoenberg asked Eisler to write for a performance that also featured Pierrot lunaire (Junko Ohtsu- Bormann is the soprano). Eisler’s piano pieces of the period were light and fresh, as, for example, is the short Andante con moto, op. 3, no.1 (Siegfried Stöckigt is the pianist).

Parallel to being involved with music, Eisler continued to be actively engaged in politics, and that, in turn, strongly affected his composition style. Eisler became a devoted Marxist and joined several radical leftist organizations, first in Austria and then, after moving to Germany in 1925, in Berlin where he applied for membership in the German Communist Party. He became disaffected with the “bourgeois” 12-tonal music and quarreled with Schoenberg who could not accept his student’s political views. Affected by ideology, Eisler switched to composing marches and solidarity songs, including Kominternlied, the unofficial hymn of the Comintern, the Soviet Union-led Communist International. Many of his songs became very popular with the European Left. They contained fighting words, and we should remember that that was the time when the Communists were literally fighting the Nazis on the streets of Germany.

In 1930 Eisler met the playwright Bertolt Brecht, one of the stars of the Left. They became lifelong friends and their cooperation led to several influential theatrical productions. We’ll finish the story of Hans Eisler during the Nazi period, his emigration and, later, his unexpected return to Germany, next week.