This Week in Classical Music: July 8, 2024. Hanns Eisler, part II.We ended the first part of our Eisler story in 1933 when the Nazis took power in Germany.Eisler’s music was immediately banned, as were his friend Brecht’s plays, and both went into exile.Brecht settled in Denmark while Eisler moved from one place to another, temporarily living in Prague, Vienna, Paris, London, Moscow, Spain in 1937, during the Civil War, and other countries.He also visited the US, twice.In 1938 he permanently moved to the US, where he received a position at the New School for Social Research in New York.In 1942 Eisler moved to California, where Brecht had been living since 1941.They continued their cooperation: Brecht wrote the script for Fritz Lang’s movie, Hangmen Also Die!, and Eisler wrote the music, which was nominated for an Oscar.Eisler wrote music for seven other Hollywood films, receiving another Oscar nomination in 1945.He continued writing music for films for the rest of his creative life, 40 of them altogether – that was a major part of his creative output.In 1947 he published a book, Composing for the Films, co-written with another German exile, the philosopher Theodor Adorno.

That same year, 1947, he was brought before the Congress’s Committee on Un-American Activities.One of his accusers was his sister, Ruth Fischer, who by then had turned into a radical anti-Stalinist.She testified before the committee against her brothers, Hanns and Gerhart.She claimed that both of them were Soviet agents.Hanns, while a committed communist who lied on his US visa application, probably wasn’t an agent, whereas Gerhart was not only a Comintern agent but also a spymaster.Hanns was a well-known figure in the Hollywood German community and, as a noted composer active in leftist causes, in Europe as well.A worldwide campaign on his behalf was organized and led by many prominent intellectuals, among them Charlie Chaplin, Thomas Mann, Albert Einstein, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Igor Stravinsky, Aaron Copland and Jean Cocteau (Stravinsky is a surprising name on this list – he wasn’t known for his liberal views).Despite all that, Hanns Eisler was expelled from the US in March of 1948. He returned to Vienna, and, after a couple of trips to East Berlin, he settled in the German Democratic Republic for good.In 1949 he composed a song, Auferstanden aus Ruinen (Risen from the ruins) which became the country’s national anthem.Eisler was elected to the Academy of Arts and, for a while, feted as the most important composer of the Republic.Brecht moved to East Berlin in 1949 and established a theater company, the Berliner Ensemble.Together, Brecht and Eisler worked on 17 plays.While much of his previous output was dedicated to music of protest, in East Germany Eisler felt compelled to write music supporting the regime.No chamber music was written – that was too bourgeois.So the main output was “applied music“ for theater and movies, and songs, many for children and some for official occasions.Not everything was going well for Eisler: he wanted to compose an opera on the Faust theme, Johannes Faustus, and wrote a libretto for it, but the libretto was severely criticized in the press.Eisler got depressed and dropped the idea.Then, in 1956, Brecht died, and that depressed Eisler even more.He was encouraged by the 20th Congress of the Soviet Communist Party and its promise of de-Stalinization, but that didn’t have much effect on the repressive regime of East Germany.A lifelong communist, Eisler became disconnected from the realities of communist Germany.He suffered two heart attacks, the second killing him in September 1962.He was buried next to Brecht in Berlin.

Here, from the last pre-Nazi year, 1932, is Eisler’s Kleine Simphonie.Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin is conducted by Hans Zimmer.

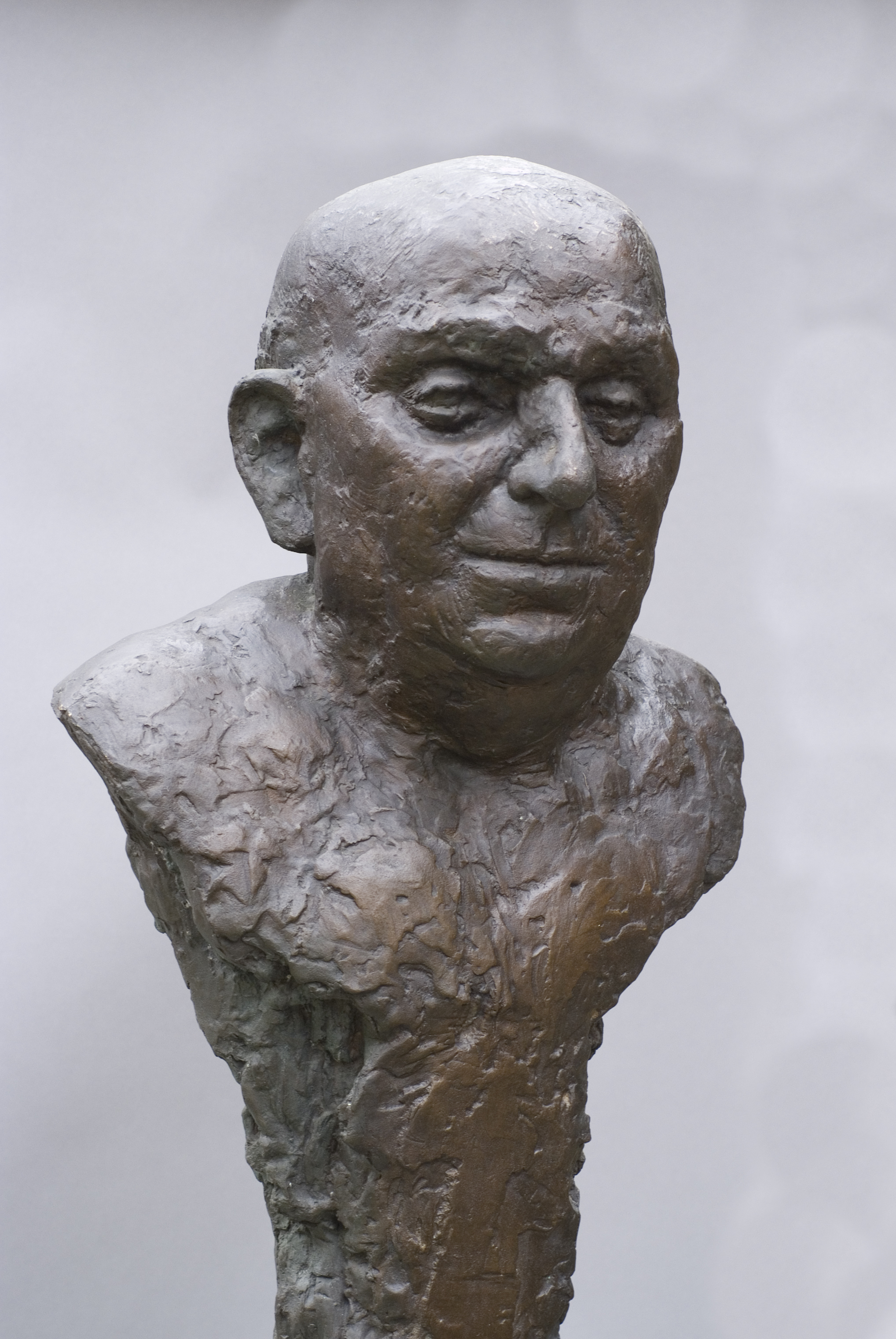

Hanns Eslier, part II, 2024

This Week in Classical Music: July 8, 2024. Hanns Eisler, part II. We ended the first part of our Eisler story in 1933 when the Nazis took power in Germany. Eisler’s music was immediately banned, as were his friend Brecht’s plays, and both went into exile. Brecht settled in Denmark while Eisler moved from one place to another, temporarily living in Prague, Vienna, Paris, London, Moscow, Spain in 1937, during the Civil War, and other countries. He also visited the US, twice. In 1938 he permanently moved to the US, where he received a position at the New School for Social Research in New York. In 1942 Eisler moved to California, where Brecht had been living since 1941. They continued their cooperation: Brecht wrote the script for Fritz Lang’s movie, Hangmen Also Die!, and Eisler wrote the music, which was nominated for an Oscar. Eisler wrote music for seven other Hollywood films, receiving another Oscar nomination in 1945. He continued writing music for films for the rest of his creative life, 40 of them altogether – that was a major part of his creative output. In 1947 he published a book, Composing for the Films, co-written with another German exile, the philosopher Theodor Adorno.

banned, as were his friend Brecht’s plays, and both went into exile. Brecht settled in Denmark while Eisler moved from one place to another, temporarily living in Prague, Vienna, Paris, London, Moscow, Spain in 1937, during the Civil War, and other countries. He also visited the US, twice. In 1938 he permanently moved to the US, where he received a position at the New School for Social Research in New York. In 1942 Eisler moved to California, where Brecht had been living since 1941. They continued their cooperation: Brecht wrote the script for Fritz Lang’s movie, Hangmen Also Die!, and Eisler wrote the music, which was nominated for an Oscar. Eisler wrote music for seven other Hollywood films, receiving another Oscar nomination in 1945. He continued writing music for films for the rest of his creative life, 40 of them altogether – that was a major part of his creative output. In 1947 he published a book, Composing for the Films, co-written with another German exile, the philosopher Theodor Adorno.

That same year, 1947, he was brought before the Congress’s Committee on Un-American Activities. One of his accusers was his sister, Ruth Fischer, who by then had turned into a radical anti-Stalinist. She testified before the committee against her brothers, Hanns and Gerhart. She claimed that both of them were Soviet agents. Hanns, while a committed communist who lied on his US visa application, probably wasn’t an agent, whereas Gerhart was not only a Comintern agent but also a spymaster. Hanns was a well-known figure in the Hollywood German community and, as a noted composer active in leftist causes, in Europe as well. A worldwide campaign on his behalf was organized and led by many prominent intellectuals, among them Charlie Chaplin, Thomas Mann, Albert Einstein, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Igor Stravinsky, Aaron Copland and Jean Cocteau (Stravinsky is a surprising name on this list – he wasn’t known for his liberal views). Despite all that, Hanns Eisler was expelled from the US in March of 1948. He returned to Vienna, and, after a couple of trips to East Berlin, he settled in the German Democratic Republic for good. In 1949 he composed a song, Auferstanden aus Ruinen (Risen from the ruins) which became the country’s national anthem. Eisler was elected to the Academy of Arts and, for a while, feted as the most important composer of the Republic. Brecht moved to East Berlin in 1949 and established a theater company, the Berliner Ensemble. Together, Brecht and Eisler worked on 17 plays. While much of his previous output was dedicated to music of protest, in East Germany Eisler felt compelled to write music supporting the regime. No chamber music was written – that was too bourgeois. So the main output was “applied music“ for theater and movies, and songs, many for children and some for official occasions. Not everything was going well for Eisler: he wanted to compose an opera on the Faust theme, Johannes Faustus, and wrote a libretto for it, but the libretto was severely criticized in the press. Eisler got depressed and dropped the idea. Then, in 1956, Brecht died, and that depressed Eisler even more. He was encouraged by the 20th Congress of the Soviet Communist Party and its promise of de-Stalinization, but that didn’t have much effect on the repressive regime of East Germany. A lifelong communist, Eisler became disconnected from the realities of communist Germany. He suffered two heart attacks, the second killing him in September 1962. He was buried next to Brecht in Berlin.

Here, from the last pre-Nazi year, 1932, is Eisler’s Kleine Simphonie. Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin is conducted by Hans Zimmer.