September 17, 2012. We have some unfinished business from the two previous weeks. With the explosion of anniversaries we had very little time to write about Arnold Schoenberg and Antonin Dvořák. With Schoenberg we traced his career to the point when he abandoned tonality in pieces such as Pierrot Lunaire, Op. 21, written in 1912. Though very radical in its completeness, Schoenberg’s atonal music was not truly revolutionary: even Wagner extensively used shifting tonalities in his operas, sometimes to such extent that the major tonal center would seem to completely disappear (many of you may have heard it last week on public television during the rebroadcast of the wonderful Ring Cycle from the Metropolitan Opera). Some works of Debussy had the same quality, but of course not to the degree as used by Schoenberg. As unusual as it sounds, the atonal music still maintains the traditional tonal relationships, except that they are dispersed in small droplets within the composition. Schoenberg didn't stop there: he evolved his style to eliminate all traces of tonality, making all 12 tones of the scale equal throughout a piece of music. This style became known as dodecaphone, or the twelve tone technique. Schoenberg "invented" it around 1921. By then he had already established a group of followers and pupils who became known as the Second Viennese School. The key participants in this group were the tremendously talented Alban Berg and Anton Webern. Among other noted members were Hanns Eisler and Viktor Ullmann. All of them continued composing in the twelve tone style, which became extremely influential by the middle of the century. Composers such as Milton Babbitt in the US, the Frenchman Pierre Boulez, the Italians Luciano Berio and Luigi Dallapiccola, and the Austrian-American Ernst Krenek were major proponents of the system. Even Stravinsky experimented with it.

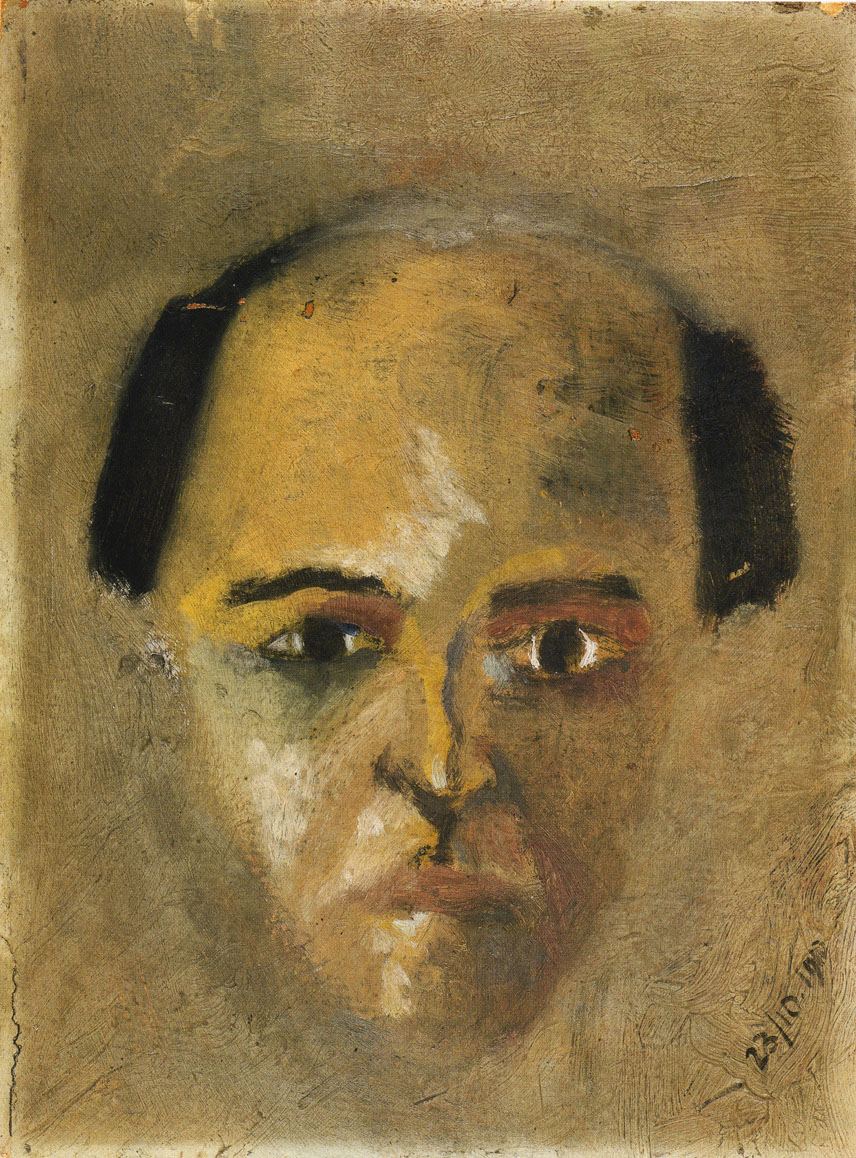

In 1924 Schoenberg moved to Berlin, accepting the position of Director of the Master Class in Composition at the Prussian Academy of Arts. He held this position till 1933, when Adolf Hitler was elected Chancellor of Germany. Fearing for his safety, Schoenberg moved to the United States and eventually settled in Los Angeles. He taught at UCLA and the University of Southern California (John Cage and Lou Harrison were among his students). He also continued composing; among the music written during this period are two concertos, one for the violin and another for the piano, and (the unfinished) opera Moses und Aron. We'll hear the first movement of the Piano concerto, performed by Mitsuko Uchida and the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, Jeffrey Tate conducting (here, courtesy of YouTube). Schoenberg was also a serious amateur painter. The picture above is a self-portrait, painted in 1910.

It's hard to imagine a composer more different than Schoenberg, but here we are, celebrating Antonin Dvořák. His anniversary was two weeks ago, but at that time we were too busy with Bruckner. It's interesting that on a superficial but factual level, one can find a lot of similarities between Schoenberg and Dvořák. A generation apart (Dvořák was born in 1841, Schoenberg in 1874) both were children of the Austrian Empire: Dvořák was born near Prague, the capital of Bohemia (now the Czech Republic), which back then was an important part of the empire, Schoenberg in Vienna. Both spent some time in the US: Schoenberg, the last 18 years of his life, Dvořák - three very productive years at the end of his. Musically, both were influenced by Brahms, which, while unnoticeable in Schoenberg's later compositions, is very clear in all of Dvořák's oeuvre. And during different periods of their respective careers, both were supported by Gustav Mahler. But as far as their compositions are concerned, while Schoenberg was a revolutionary, Dvořák was everything but. Which of course doesn't mean that he didn't write some wonderful music: his "New World" symphony, the cello concerto, the opera "Rusalka," some songs, quartets, and piano music are first class. Here is his Piano Quintet in A major, Op. 81. It's performed by Tessa Lark andYoon-Jung Yang, violins, Yiyin Li, viola, Sébastien Gingras, cello and Helen Huang, piano.

Schoenberg and Dvořák 2012

September 17, 2012. We have some unfinished business from the two previous weeks. With the explosion of anniversaries we had very little time to write about Arnold Schoenberg and Antonin Dvořák. With Schoenberg we traced his career to the point when he abandoned tonality in pieces such as Pierrot Lunaire, Op. 21, written in 1912. Though very radical in its completeness, Schoenberg’s atonal music was not truly revolutionary: even Wagner extensively used shifting tonalities in his operas, sometimes to such extent that the major tonal center would seem to completely disappear (many of you may have heard it last week on public television during the rebroadcast of the wonderful Ring Cycle from the Metropolitan Opera). Some works of Debussy had the same quality, but of course not to the degree as used by Schoenberg. As unusual as it sounds, the atonal music still maintains the traditional tonal relationships, except that they are dispersed in small droplets within the composition. Schoenberg didn't stop there: he evolved his style to eliminate all traces of tonality, making all 12 tones of the scale equal throughout a piece of music. This style became known as dodecaphone, or the twelve tone technique. Schoenberg "invented" it around 1921. By then he had already established a group of followers and pupils who became known as the Second Viennese School. The key participants in this group were the tremendously talented Alban Berg and Anton Webern. Among other noted members were Hanns Eisler and Viktor Ullmann. All of them continued composing in the twelve tone style, which became extremely influential by the middle of the century. Composers such as Milton Babbitt in the US, the Frenchman Pierre Boulez, the Italians Luciano Berio and Luigi Dallapiccola, and the Austrian-American Ernst Krenek were major proponents of the system. Even Stravinsky experimented with it.

traced his career to the point when he abandoned tonality in pieces such as Pierrot Lunaire, Op. 21, written in 1912. Though very radical in its completeness, Schoenberg’s atonal music was not truly revolutionary: even Wagner extensively used shifting tonalities in his operas, sometimes to such extent that the major tonal center would seem to completely disappear (many of you may have heard it last week on public television during the rebroadcast of the wonderful Ring Cycle from the Metropolitan Opera). Some works of Debussy had the same quality, but of course not to the degree as used by Schoenberg. As unusual as it sounds, the atonal music still maintains the traditional tonal relationships, except that they are dispersed in small droplets within the composition. Schoenberg didn't stop there: he evolved his style to eliminate all traces of tonality, making all 12 tones of the scale equal throughout a piece of music. This style became known as dodecaphone, or the twelve tone technique. Schoenberg "invented" it around 1921. By then he had already established a group of followers and pupils who became known as the Second Viennese School. The key participants in this group were the tremendously talented Alban Berg and Anton Webern. Among other noted members were Hanns Eisler and Viktor Ullmann. All of them continued composing in the twelve tone style, which became extremely influential by the middle of the century. Composers such as Milton Babbitt in the US, the Frenchman Pierre Boulez, the Italians Luciano Berio and Luigi Dallapiccola, and the Austrian-American Ernst Krenek were major proponents of the system. Even Stravinsky experimented with it.

In 1924 Schoenberg moved to Berlin, accepting the position of Director of the Master Class in Composition at the Prussian Academy of Arts. He held this position till 1933, when Adolf Hitler was elected Chancellor of Germany. Fearing for his safety, Schoenberg moved to the United States and eventually settled in Los Angeles. He taught at UCLA and the University of Southern California (John Cage and Lou Harrison were among his students). He also continued composing; among the music written during this period are two concertos, one for the violin and another for the piano, and (the unfinished) opera Moses und Aron. We'll hear the first movement of the Piano concerto, performed by Mitsuko Uchida and the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, Jeffrey Tate conducting (here, courtesy of YouTube). Schoenberg was also a serious amateur painter. The picture above is a self-portrait, painted in 1910.

It's hard to imagine a composer more different than Schoenberg, but here we are, celebrating Antonin Dvořák. His anniversary was two weeks ago, but at that time we were too busy with Bruckner. It's interesting that on a superficial but factual level, one can find a lot of similarities between Schoenberg and Dvořák. A generation apart (Dvořák was born in 1841, Schoenberg in 1874) both were children of the Austrian Empire: Dvořák was born near Prague, the capital of Bohemia (now the Czech Republic), which back then was an important part of the empire, Schoenberg in Vienna. Both spent some time in the US: Schoenberg, the last 18 years of his life, Dvořák - three very productive years at the end of his. Musically, both were influenced by Brahms, which, while unnoticeable in Schoenberg's later compositions, is very clear in all of Dvořák's oeuvre. And during different periods of their respective careers, both were supported by Gustav Mahler. But as far as their compositions are concerned, while Schoenberg was a revolutionary, Dvořák was everything but. Which of course doesn't mean that he didn't write some wonderful music: his "New World" symphony, the cello concerto, the opera "Rusalka," some songs, quartets, and piano music are first class. Here is his Piano Quintet in A major, Op. 81. It's performed by Tessa Lark and Yoon-Jung Yang, violins, Yiyin Li, viola, Sébastien Gingras, cello and Helen Huang, piano.