March 11, 2013.Van Cliburn may have been more of a pianist than a musician, and a cultural phenomenon above all, but he affected the lives of millions of people, and that alone has secured him a unique place in the musical Pantheon.His recordings of Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto and Rachmaninov’s Third are among the very finest; and even though his name won’t be mentioned in the same breath as Rubinstein, Richter, Horowitz, Michelangeli or Brendel’s, his death on February 27, 2013 of bone cancer was an event that made the front pages of all the major newspapers and news channels around the world.

When Cliburn came to Moscow in the spring of 1958, he was an acknowledged talent with a sputtering career.He studied with Rosina Lhévinne at the Juilliard, receiving a diploma in 1954.That year he won the prestigious Leventritt competition, which earned him an appearance at the Carnegie Hall.But the mid-1950s also witnessed the ascent of an extraordinary group of young American pianists: Leon Fleisher, Byron Janis, Daniel Pollack, John Browning, Gary Graffman.And of course Arthur Rubinstein, though in his mid-60s, was still playing exceptionally well (Vladimir Horowitz was on one of his famous hiatus).All in all, a difficult time to start a major career.It was Rosina Lhévinne who suggested that her former pupil enter the first international Tchaikovsky competition.Ms. Lhévinne graduated from the Moscow Conservatory with the Gold Medal, and so did her future husband Josef; both studied with Vasily Safonov.They emigrated from Russia before the First World War and eventually settled in New York.In America, Josef Lhévinne, who by all accounts possessed a prodigious technique, had a small career as a concert pianist, but preferred to teach at the Juilliard.Rosina worked as his assistant, and took over his class after Josef‘s death.It became one of the most celebrated in the history of Juilliard.

As Cliburn later said in one of his interviews, he thought his prospects going to the Tchaikovsky competition were not very good, as he expected a Soviet pianist to win.So did the Soviet musical establishment.In a country where classical music occupied a very special place, both socially and politically, and successful musicians were feted by the State, the first international competition was an event of great magnitude.Its results were not to be taken lightly.The country was represented by several established, first-rate pianists, Lev Vlasenko and Naum Shtarkman among them (Shtarkman was already 30, older than the maximum allowed age, but organizers let him participate nonetheless).Cliburn played well during the first round and was admitted to the second; word about the talented American with Russian musical roots started spreading around Moscow.

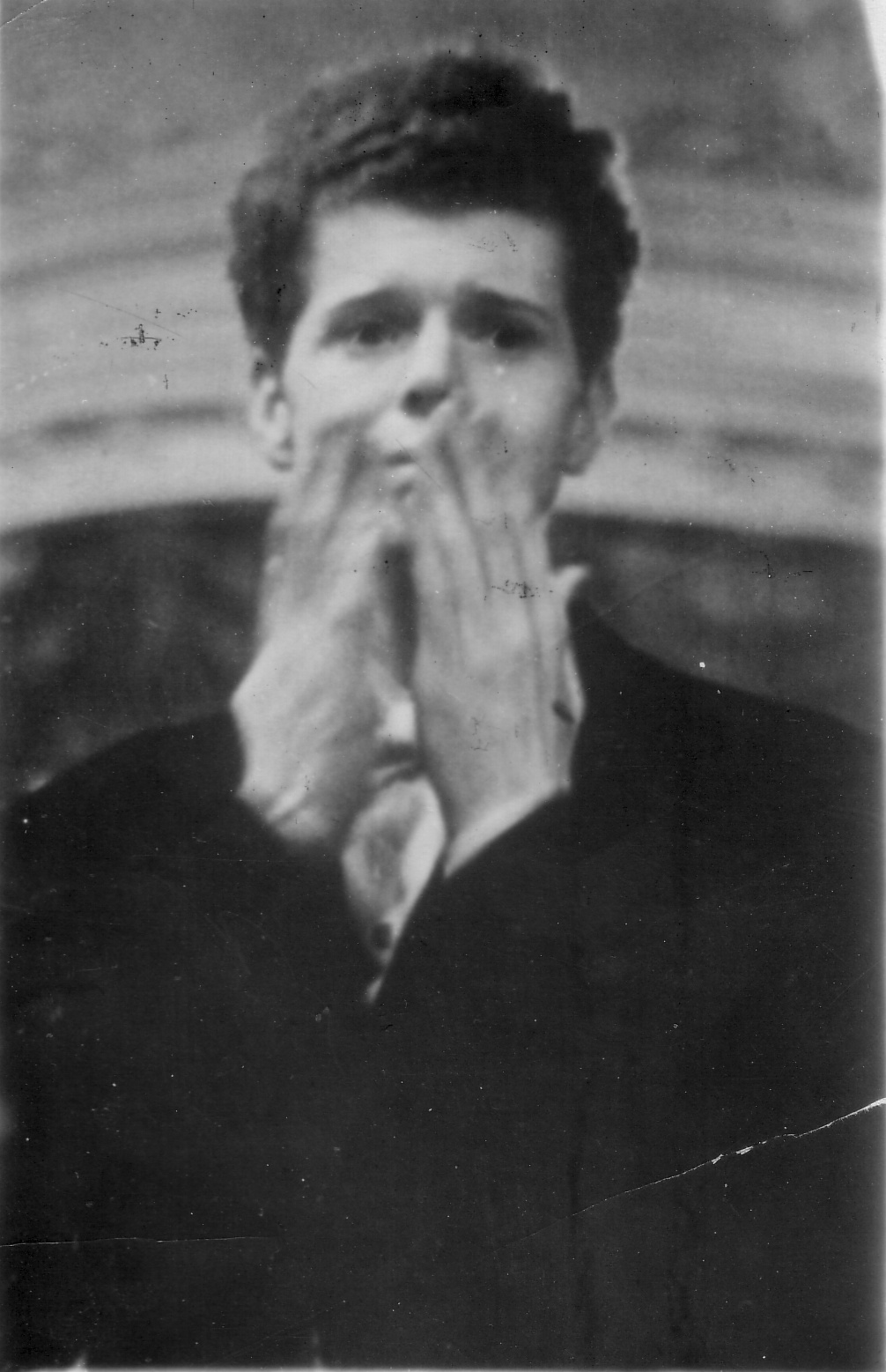

He played his second round program, which included Chopin’s Fantasy in F minor, Op. 49 and Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody no. 12, brilliantly.Sviatoslav Richter, a member of the piano jury, gave Cliburn 25 points, the highest mark.(The jury itself was spectacular: Emil Gilels was the Chairman, and among the members were Henrich Neuhaus, Dmitry Kabalevsky, Lev Oborin, and Carlo Zecchi).By the third, and final round, Cliburn was the clear favorite not only of the jury but of the public as well.To appreciate the excitement the Competition generated in Moscow, one has to remember the atmosphere of 1958.It was just five years since Stalin’s death.The Russian society, shut down behind the Curtain and traumatized by the terror of the previous 40 years, was opening up, just a bit, during Khrushchev’s “thaw.”People were yearning for new things, and the gangly, 6-foot-4, smiling and irresistibly charming American, who for an average Muscovite looked like an alien, perfectly personified these desires.

The final round was a triumph.The requisite Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov’s Third were spectacular.When Cliburn finished, the public was on its feet, screaming “winner, winner.” In a highly unusual move, Gilels, the jury chairman, went backstage to congratulate him.Richter called him a genius, adding that he does not use the term lightly.Giving the first prize to an American required Khrushchev’s consent, but the premier, charmed as everybody else, approved.The post-competition concerts in Leningrad and again in Moscow were immensely successful.In the US the win also generated tremendous enthusiasm.Just one year earlier, the US was stunned when the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, thus undermining the idea of American technological superiority, and here was a young Texan, who beat the Russians in the cultural field, probably the only area in which the American psyche was still somewhat unsure of itself.New York welcomed Cliburn with a ticker-tape parade, an event unimaginable these days.Time magazine featured his photo with the caption: “The Texan who conquered Russia.”He made a recording of Tchaikovsky’s First Piano concerto with Kirill Kondrashin for RCA, and it sold more than one million copies, eventually going triple-platinum (apparently, still a record for a recording of a concerto).He went on tour of major American concert halls.But as it turned out the years 1958 and ’59 were the peak of his career.The public, and Sol Hurok, his impresario, wanted him to play the Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov concertos over and over, and Cliburn had to oblige.In his recitals, Cliburn attempted to expand the repertory but was met with criticism.He went back to Moscow in 1960 and 1962; the general public still adored him, but some critics were less than satisfied.The consensus was that while he played some pieces extremely well, (Prokofiev’s Third Piano concerto was one of them) other things worked less successfully, Beethoven in particular.His concert schedule became less active, and by 1978 he dropped off the concert scene.

In the end, it doesn’t matter all that much.Cliburn left us several wonderful recordings, conquered Russia and changed the history of two countries.Here’s the historical 1958 recording of the Tachikovsky First piano concerto in B-flat minor.Van Clibrun, Kirill Kondrashin, RCA Symphony orchestra.

Van Cliburn, appreciation

March 11, 2013. Van Cliburn may have been more of a pianist than a musician, and a cultural phenomenon above all, but he affected the lives of millions of people, and that alone has secured him a unique place in the musical Pantheon. His recordings of Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto and Rachmaninov’s Third are among the very finest; and even though his name won’t be mentioned in the same breath as Rubinstein, Richter, Horowitz, Michelangeli or Brendel’s, his death on February 27, 2013 of bone cancer was an event that made the front pages of all the major newspapers and news channels around the world.

Rachmaninov’s Third are among the very finest; and even though his name won’t be mentioned in the same breath as Rubinstein, Richter, Horowitz, Michelangeli or Brendel’s, his death on February 27, 2013 of bone cancer was an event that made the front pages of all the major newspapers and news channels around the world.

When Cliburn came to Moscow in the spring of 1958, he was an acknowledged talent with a sputtering career. He studied with Rosina Lhévinne at the Juilliard, receiving a diploma in 1954. That year he won the prestigious Leventritt competition, which earned him an appearance at the Carnegie Hall. But the mid-1950s also witnessed the ascent of an extraordinary group of young American pianists: Leon Fleisher, Byron Janis, Daniel Pollack, John Browning, Gary Graffman. And of course Arthur Rubinstein, though in his mid-60s, was still playing exceptionally well (Vladimir Horowitz was on one of his famous hiatus). All in all, a difficult time to start a major career. It was Rosina Lhévinne who suggested that her former pupil enter the first international Tchaikovsky competition. Ms. Lhévinne graduated from the Moscow Conservatory with the Gold Medal, and so did her future husband Josef; both studied with Vasily Safonov. They emigrated from Russia before the First World War and eventually settled in New York. In America, Josef Lhévinne, who by all accounts possessed a prodigious technique, had a small career as a concert pianist, but preferred to teach at the Juilliard. Rosina worked as his assistant, and took over his class after Josef‘s death. It became one of the most celebrated in the history of Juilliard.

As Cliburn later said in one of his interviews, he thought his prospects going to the Tchaikovsky competition were not very good, as he expected a Soviet pianist to win. So did the Soviet musical establishment. In a country where classical music occupied a very special place, both socially and politically, and successful musicians were feted by the State, the first international competition was an event of great magnitude. Its results were not to be taken lightly. The country was represented by several established, first-rate pianists, Lev Vlasenko and Naum Shtarkman among them (Shtarkman was already 30, older than the maximum allowed age, but organizers let him participate nonetheless). Cliburn played well during the first round and was admitted to the second; word about the talented American with Russian musical roots started spreading around Moscow.

He played his second round program, which included Chopin’s Fantasy in F minor, Op. 49 and Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody no. 12, brilliantly. Sviatoslav Richter, a member of the piano jury, gave Cliburn 25 points, the highest mark. (The jury itself was spectacular: Emil Gilels was the Chairman, and among the members were Henrich Neuhaus, Dmitry Kabalevsky, Lev Oborin, and Carlo Zecchi). By the third, and final round, Cliburn was the clear favorite not only of the jury but of the public as well. To appreciate the excitement the Competition generated in Moscow, one has to remember the atmosphere of 1958. It was just five years since Stalin’s death. The Russian society, shut down behind the Curtain and traumatized by the terror of the previous 40 years, was opening up, just a bit, during Khrushchev’s “thaw.” People were yearning for new things, and the gangly, 6-foot-4, smiling and irresistibly charming American, who for an average Muscovite looked like an alien, perfectly personified these desires.

The final round was a triumph. The requisite Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov’s Third were spectacular. When Cliburn finished, the public was on its feet, screaming “winner, winner.” In a highly unusual move, Gilels, the jury chairman, went backstage to congratulate him. Richter called him a genius, adding that he does not use the term lightly. Giving the first prize to an American required Khrushchev’s consent, but the premier, charmed as everybody else, approved. The post-competition concerts in Leningrad and again in Moscow were immensely successful. In the US the win also generated tremendous enthusiasm. Just one year earlier, the US was stunned when the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, thus undermining the idea of American technological superiority, and here was a young Texan, who beat the Russians in the cultural field, probably the only area in which the American psyche was still somewhat unsure of itself. New York welcomed Cliburn with a ticker-tape parade, an event unimaginable these days. Time magazine featured his photo with the caption: “The Texan who conquered Russia.” He made a recording of Tchaikovsky’s First Piano concerto with Kirill Kondrashin for RCA, and it sold more than one million copies, eventually going triple-platinum (apparently, still a record for a recording of a concerto). He went on tour of major American concert halls. But as it turned out the years 1958 and ’59 were the peak of his career. The public, and Sol Hurok, his impresario, wanted him to play the Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov concertos over and over, and Cliburn had to oblige. In his recitals, Cliburn attempted to expand the repertory but was met with criticism. He went back to Moscow in 1960 and 1962; the general public still adored him, but some critics were less than satisfied. The consensus was that while he played some pieces extremely well, (Prokofiev’s Third Piano concerto was one of them) other things worked less successfully, Beethoven in particular. His concert schedule became less active, and by 1978 he dropped off the concert scene.

In the end, it doesn’t matter all that much. Cliburn left us several wonderful recordings, conquered Russia and changed the history of two countries. Here’s the historical 1958 recording of the Tachikovsky First piano concerto in B-flat minor. Van Clibrun, Kirill Kondrashin, RCA Symphony orchestra.