Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

November 10, 2014. Couperin, Borodin, Hindemith. François Couperin, one of the greatest French Baroque composers, was born on this day in 1668. He came from a large family of musicians, some of them very talented (you can read more about the Couperins in our earlier post). He was incomparable as a composer for the harpsichord (clavecin, as it is called in French). Couperin wrote four Books for the harpsichord, each containing several “orders,” 27 orders altogether. One of the pieces in Order 6 (Book 2) is called Les Barricades Mistérieuses (The mysterious barricades); it was written in 1717. Nobody knows for sure why Couperin used this unusual title, although many suggestions have been made, from rather risqué to outlandish. In any event, here it is, performed by Scott Ross. (A talented American harpsichordist who spent most of his life in Canada and France, Ross had a tragically short life: he died in 1989 at the age of 38. Ross recorded all keyboard compositions by Couperin, all 555 sonatas by Domenico Scarlatti, and many other works by the Baroque composers).

in our earlier post). He was incomparable as a composer for the harpsichord (clavecin, as it is called in French). Couperin wrote four Books for the harpsichord, each containing several “orders,” 27 orders altogether. One of the pieces in Order 6 (Book 2) is called Les Barricades Mistérieuses (The mysterious barricades); it was written in 1717. Nobody knows for sure why Couperin used this unusual title, although many suggestions have been made, from rather risqué to outlandish. In any event, here it is, performed by Scott Ross. (A talented American harpsichordist who spent most of his life in Canada and France, Ross had a tragically short life: he died in 1989 at the age of 38. Ross recorded all keyboard compositions by Couperin, all 555 sonatas by Domenico Scarlatti, and many other works by the Baroque composers).

The chemist, doctor and accidental composer of great talent, Alexander Borodin was born on November 12th of 1833. All his life Borodin was mostly interested in sciences, studying in St.-Petersburg and universities abroad and eventually obtaining a teaching position at the prestigious Medical-Surgical Academy. Music was a love, and composing – a pleasant hobby. In 1862, at the home of his colleague, the famous doctor Sergey Botkin, Borodin met Mily Balakirev and then through Balakirev, he made friends with Cesar Cui, Modest Mussorgsky, and the young Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Five years later the music critic Vladimir Stasov would call them the Mighty Five. The 1862 meeting strongly affected Borodin, and almost immediately he started working on his 1st Symphony. Even though he wrote three of them, some chamber music, and most of Prince Igor, a truly great opera (it fell upon Rimsky-Korsakov and Glazunov to finish it after Borodin’s death), he never made composing his main profession. In 1880 Borodin wrote a symphonic poem In the Steppes of Central Asia (the original Russian title was just “Central Asia”). In 1908, a Frenchman by the name of Joseph-Louis Mundwiller shot a documentary called Moscow Clad in Snow (and it really was that year). It’s a fascinating film that shows Moscow at the beginning of the 20th century, much of which doesn’t exist any longer. When the movie was restored, the editors decided that Borodin’s In the Steppes would go well as an accompaniment. Even though there are thousands of miles between Moscow and Central Asia, somehow it worked. Here is In the Steppes of Central Asia as performed by Kurt Sanderling and Dresden Staatskapelle. And here is the movie on YouTube. It’s worth watching even if you’ve have never been to Moscow.

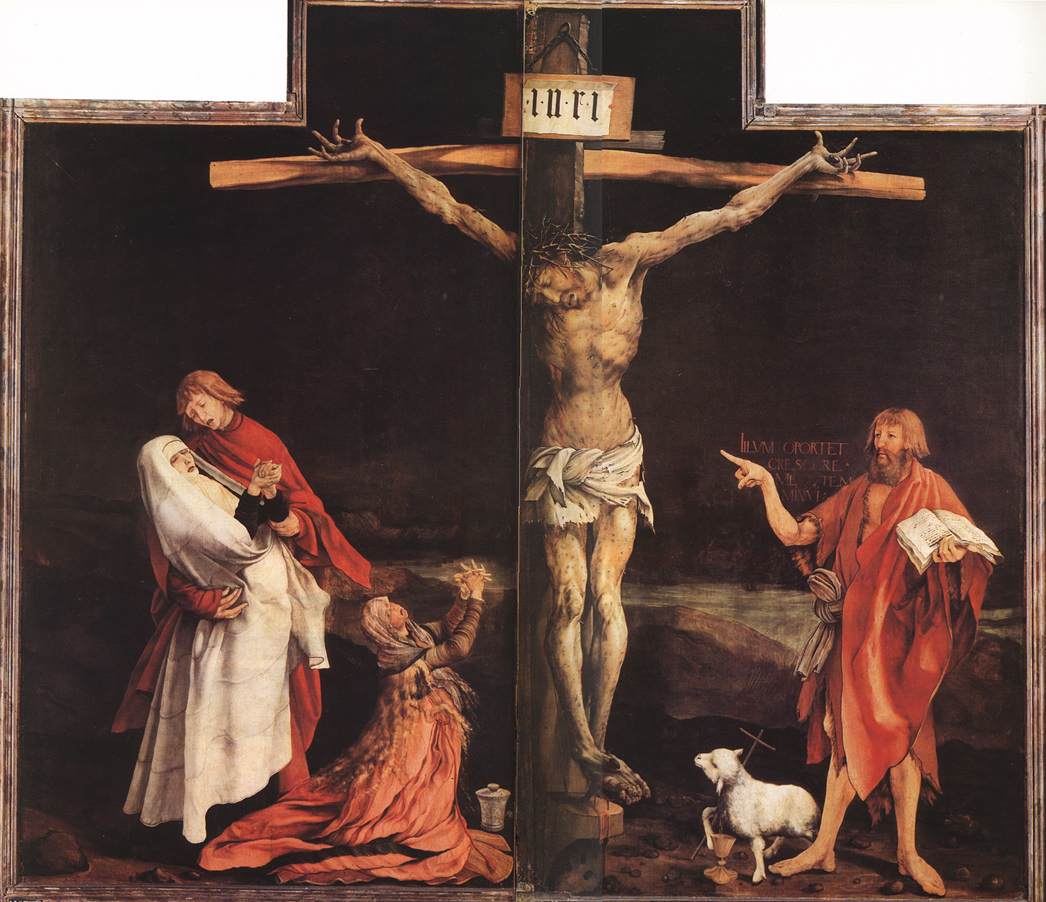

One of the most important German composers of the 20th century, Paul Hindemith was born on November 16th, 1895. We need to dedicate an entry to him alone, but right now we’ll present one of his most famous compositions, the symphony Mathis der Maler (Matthias the Painter). “Mathis” in the title is Matthias Grünewald, a German Renaissance painter who lived from 1470 to 1528. His greatest work was the so-called Isenheim Altarpiece, which consists of a large central panel depicting the Crucifixion and several side panels with the Annunciation, several saints, the visit of Saint Anthony to Saint Paul the Hermit and other biblical and apocryphal stories. The side panels can be opened and closed, creating different views of the altar. The altarpiece is an absolute pinnacle of German art; the power of it is as overwhelming today as it was 500 years ago. Located in a museum in the Alsatian city of Colmar it is very much worth the trip, as the Michelin guide would put it, even though Colmar itself is not a very interesting place (but of course if you’re there, you’ve already made it to Strasbourg). If the trip to Alsace isn’t in your plans, then you can go to the Web Gallery of Art and view it there. Mathis der Maler consists of three movements, each corresponding to a separate panel: Angelic Concert, Entombment, and The Temptation of Saint Anthony. Here it is, in the performance by the London Symphony Orchestra, Jascha Horenstein conducting.

November 16th, 1895. We need to dedicate an entry to him alone, but right now we’ll present one of his most famous compositions, the symphony Mathis der Maler (Matthias the Painter). “Mathis” in the title is Matthias Grünewald, a German Renaissance painter who lived from 1470 to 1528. His greatest work was the so-called Isenheim Altarpiece, which consists of a large central panel depicting the Crucifixion and several side panels with the Annunciation, several saints, the visit of Saint Anthony to Saint Paul the Hermit and other biblical and apocryphal stories. The side panels can be opened and closed, creating different views of the altar. The altarpiece is an absolute pinnacle of German art; the power of it is as overwhelming today as it was 500 years ago. Located in a museum in the Alsatian city of Colmar it is very much worth the trip, as the Michelin guide would put it, even though Colmar itself is not a very interesting place (but of course if you’re there, you’ve already made it to Strasbourg). If the trip to Alsace isn’t in your plans, then you can go to the Web Gallery of Art and view it there. Mathis der Maler consists of three movements, each corresponding to a separate panel: Angelic Concert, Entombment, and The Temptation of Saint Anthony. Here it is, in the performance by the London Symphony Orchestra, Jascha Horenstein conducting.

PermalinkNovember 3, 2014. Années de Pèlerinage, Deuxième Année: Italie. Even though today is the birthday of Vincenzo Bellini (he was born in 1801 in Catania, Sicily, and we’ve written about him extensively in the past, here and here), we’ll continue the traversal of Franz Liszt’s Années de Pèlerinage. This time it’s the second year of the pilgrimage, and we’re in Italy. As always, we’ll illustrate every piece with performances by pianists young and renowned: the Canadian Jason Cutmore plays Sposalizio and Canzonetta del Salvator Rosa, the great Alfred Brendel plays Penseroso, Lazar Berman plays the first two of the three Sonetto del Petrarca, Sonetto.47 and Sonetto 104, and the legendary Russian pianist Vladimir Sofronitsky – Sonetto 123, in a 1952 recording. Finally, the young Swiss pianist Beatrice Berrut plays what Liszt called “Fantasia Quasi Sonata” Après une Lecture de Dante. Here’s the article by Joseph DuBose.

Deuxième Année opens with Liszt’s musical portrayal of Raphael’s The Marriage of the Virgin in “Sposalizio” (here). The innocence and reverence of the subject matter is displayed in the simple pentatonic melody of the opening measures, stated without any further adornment, and answered by an expectant motif tucked within the inner tones of contrasting chords. Repeated incessantly, the pentatonic theme drives the first section of the piece, through wide-ranging harmonies, to a fortissimo conclusion in E major. A brief passage, combining the fragments of the theme with the answering motif, then leads the listener into the piece’s second main theme. A pious wedding march in G major, this new theme, given in a rich, chordal texture, is accompanied by the pentatonic theme. At first, its appearance is only occasional. However, following a modulation back into the tonic key of E major and the recommencement of the wedding march, the pentatonic theme becomes a permanent fixture of the accompaniment. Against the wedding march, it creates a glistening accompaniment of almost Impressionistic colors, and an continuous flow of energy that climaxes in the expectant motif of the beginning. From thence, the music recedes, with the pentatonic theme still heard above echoes of the wedding march, into the final, quiet tonic chords. (Continue).

PermalinkOctober 27, 2014. Paganini and Berio. Today is the birthday of Niccolò Paganini, who was born in Genoa in 1782. As a composer he’s best known for his 24 caprices for violin solo and several violin concertos. So here, to celebrate, are two caprices, played by two of the greatest violinists of the 20th century, David Oistrach (caprice no. 17, recorded in 1946) and Jascha Heifetz (Caprice no. 13, in a somewhat unnecessary arrangement for the violin and piano, with Brooks Smith, recorded in 1956).

Last week we wrote about Liszt’s first book of Années de pèlerinage and didn’t have time to mark the 89th birthday of the Italian composer Luciano Berio, who was born on October 24th of 1925. Berio was one of the most interesting composers of the second half of the 20th century. Born into a musical family (both his father and grandfather were organists and composers) he started studying music at an early age. During the war he was conscripted by Mussolini’s Republic of Salò, but injured himself in training and spent most of the time in a hospital. When the war was over, he went to Milan to study piano and composition but his injured hand cut short his piano aspirations. His early compositions were written in the neo-classical style of the Stravinsky type, but he soon became interested in the avant-garde music and especially in serialism. In 1952 he went to the US to study with Luigi Dallapiccola in Tangelwood. Dallapiccola, also an Italian, was the major proponent of serialism, being influenced by Webern and Berg.

Berio then attended several of the International summer courses in Darmstadt, at that time the epicenter for new music in Europe. Darmstadt was the place for young composers and music theoreticians to listen to music, lecture, argue, and share ideas. Among the participants were Stockhausen, Boulez, Ligeti, Milton Babbit, Hanz Werner Henze and many others. Theodor Adorno, the leading philosopher and musicologist, was one of the active participants. In the 1960s Berio spent a lot of time in the US, teaching at Tanglewood and Juilliard. Interested in electronic music, he went to Paris and became a co-director of IRCAM (Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique), a place associated with the name of Pierre Boulez and one of the leading centers of research in new music in general and electro-acoustical music in particular. After returning to Italy in the 1980s, Berio created a similar center in Florence, called Tempo Reale. Though he was a sought-after teacher and traveled constantly, he bought some land and buildings in the village of Radicondoli, not far from Siena. That became his base, especially after his third marriage to Talia Pecker, an Israeli musicologist. Berio continued to actively travel, conduct and compose till the end. He died in Rome on May 27, 2003.

Berio possessed a wonderful intellectually curiosity which went well beyond music. In the 1950s he collaborated with Umberto Eco, a philosopher, novelist and literary critic. Together they produce several radio programs on language and sound - for example, words that are formed by sounds that describe their meaning (like “cuckoo,” for example, or “roar”; the fancy name for it is “onomatopoeia”). Eco also got Berio interested in semiotics, the study of symbols and signs. Later in his life Berio collaborated with the writer Italo Calvino and the architect Renzo Piano.

Berio worked in many different styles, from pieces for solo instruments to orchestral works for operas. He wrote a series of works for different instruments calls Sequenza. The first Sequenza, for flute, was written in 1956, the last Sequenza XIV, for cello, in 2002. From 1950 to 1964 Berio was married to Cathy Berberian, an American mezzo-soprano (they met in Milan, while studying at the conservatory). Sequenza III, for voice, written in 1965, and dedicated to her. And here she is, singing this piece. Berio’s Sinfonia was commissioned by the New York Philharmonic and premiered in 1968. Here’s the first movement, performed by the Orchestre National de France under direction of Pierre Boulez, with and the Swingle Singers, 1969.Permalink

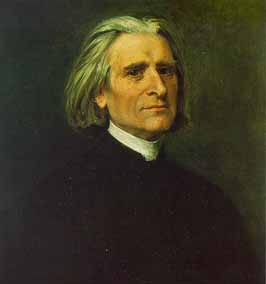

October 20, 2014. Franz Liszt. We’re marking the 113th birthday anniversary of the great Hungarian composer. Liszt was born on October 22nd of 1811 in a small village of Doborján (after the First World War that part of western Hungary was given to Austria; the town is now called Raiding). He grew up to become the greatest pianist of his time (and some believe of all time) and one of the most important composers of the 19th century. To celebrate, we‘re publishing an article by Joseph DuBose on the first of the three Années de pèlerinage piano suites, Première année: Suisse. We illustrate each piece (there are nine altogether in Première année) with performances by two young English pianists, Ashley Wass and Sodi Braide, both recorded in concerts, and two great Lisztians, the Cuban-American Jorge Bolet (1914 – 1990) and the Russian pianist Lazar Berman (1930 – 2005). The article follows. ♫

Raiding). He grew up to become the greatest pianist of his time (and some believe of all time) and one of the most important composers of the 19th century. To celebrate, we‘re publishing an article by Joseph DuBose on the first of the three Années de pèlerinage piano suites, Première année: Suisse. We illustrate each piece (there are nine altogether in Première année) with performances by two young English pianists, Ashley Wass and Sodi Braide, both recorded in concerts, and two great Lisztians, the Cuban-American Jorge Bolet (1914 – 1990) and the Russian pianist Lazar Berman (1930 – 2005). The article follows. ♫

In early June 1835, Franz Liszt traveled from Paris to Switzerland. There, in Geneva, he met his mistress, Marie d’Agoult, who had recently left her husband and family for him. Over the next four years, they lived and journeyed throughout Switzerland and Italy. Inspired by the wondrous scenery of Switzerland and the rich cultural heritage of Italy, Liszt composed during these years a suite of piano pieces entitled Album d’un voyageur, a title which he likely adapted from that of a letter from George Sand: Lettre d’un voyageur. The suite was later published in 1842, after his relationship with d’Agoult had ended and he had returned to the life a touring virtuoso. However, Album would prove to be only the genesis of a much more significant collection of pieces. Between 1848 and 1854, Liszt revised several of its constituent pieces to form the first volume (Première année: Suisse) of his Années de pèlerinage (Years of Pilgrimage)—indeed, only two emerged relatively unaltered. Besides being personal reflections of Liszt’s travels, the pieces that ultimately became part of Première année were imbued with a keen sense of the Romantic literature of his time. The title of Années de pèlerinage itself is a certain reference to Goethe’s famous novel Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahr, but mostly significantly, its sequel Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahr, which in is first French translation was translated as “Years of Wanderings.” Furthermore, each piece was headed by quotations from Schiller, Byron, and Senancour, leading figures of the burgeoning Romantic Movement. The final result, Première Année: Suisse, was published in 1855. (Continue reading here.)Permalink

October 13, 2014. Jacob Obrecht. We’ve never written about Jacob Obrecht, which is quite an omission, as he was one of the most famous composers of his time. Obrecht was born in 1457 or 1458, which makes him an almost exact contemporary of Josquin des Prez. Obrech was born in Ghent, one of most important cities in Flanders, which were then ruled by the Dukes of Burgundy (Josquin, on the other hand, was born in the county of Hainaut, about 100 miles south of Ghent. Hainaut was also ruled by the Burgundians but was a French-speaking county, whereas in Ghent Flemish was spoken). Obrecht’s father was the city trumpeter who also played at the court. It seems that Jacob was close to his father: upon his death he wrote a motet, Mille Quingentis, in his honor (here, performed by The Clerks' Group). It’s likely that Jacob also played the trumpet and that his father introduced him to the court, where he would’ve met Antoine Busnois, the favorite composer of Charles the Bold (some musicologists discern the influence of Bunois in Obrecht’s masses). Obrecht achieved fame early in his life: in the treaties published in mid-1480s, Johannes Tinctoris, a composer and music theorist, mentions him among the most renowned composer of the century; at that time Obrecht wasn’t even 30 years old. In 1484 Obrecht assumed the position of choirmaster at the Cambrai cathedral (famous at its time, the cathedral was destroyed during the French Revolution, the same fate asso many other old churches). He didn’t stay there for long, however: just one year later he was accused of embezzling money from the cathedral and had to leave. He went to Bruges, where he found a similar position. Two years later, in 1487, Duke Ercole d'Este I of Ferrara invited him to his court, and he stayed for almost a year. Obrecht was dismissed from his post in Bruges in 1490 (the reason for which we don’t know) and for the following 14 years he moved from one city in Flanders to another – Antwerp, Bergen, then Bruges again – working in the cathedrals and composing. In 1504 he returned to Ferrara, hired by his enthusiastic patron, Duke Ercole. In Ferrara he replaced Josquin, who left the city probably to escape an outbreak of the plague. Obrecht’s stay in Ferrara wasn’t long. In June of 1505 the Duke died. Obrecht tried, unsuccessfully, to obtain a position in Mantua where the ruler, Francesco II Gonzaga, was married to Isabella d'Este, the daughter of Ercole and whose court was famous as a cultural and music center. Obrecht remained in Ferrara and a couple of months later yet another outbreak of the plague caught up with him; he died on August 1st of 1505. He wasn’t even 50 years old.

Burgundy (Josquin, on the other hand, was born in the county of Hainaut, about 100 miles south of Ghent. Hainaut was also ruled by the Burgundians but was a French-speaking county, whereas in Ghent Flemish was spoken). Obrecht’s father was the city trumpeter who also played at the court. It seems that Jacob was close to his father: upon his death he wrote a motet, Mille Quingentis, in his honor (here, performed by The Clerks' Group). It’s likely that Jacob also played the trumpet and that his father introduced him to the court, where he would’ve met Antoine Busnois, the favorite composer of Charles the Bold (some musicologists discern the influence of Bunois in Obrecht’s masses). Obrecht achieved fame early in his life: in the treaties published in mid-1480s, Johannes Tinctoris, a composer and music theorist, mentions him among the most renowned composer of the century; at that time Obrecht wasn’t even 30 years old. In 1484 Obrecht assumed the position of choirmaster at the Cambrai cathedral (famous at its time, the cathedral was destroyed during the French Revolution, the same fate asso many other old churches). He didn’t stay there for long, however: just one year later he was accused of embezzling money from the cathedral and had to leave. He went to Bruges, where he found a similar position. Two years later, in 1487, Duke Ercole d'Este I of Ferrara invited him to his court, and he stayed for almost a year. Obrecht was dismissed from his post in Bruges in 1490 (the reason for which we don’t know) and for the following 14 years he moved from one city in Flanders to another – Antwerp, Bergen, then Bruges again – working in the cathedrals and composing. In 1504 he returned to Ferrara, hired by his enthusiastic patron, Duke Ercole. In Ferrara he replaced Josquin, who left the city probably to escape an outbreak of the plague. Obrecht’s stay in Ferrara wasn’t long. In June of 1505 the Duke died. Obrecht tried, unsuccessfully, to obtain a position in Mantua where the ruler, Francesco II Gonzaga, was married to Isabella d'Este, the daughter of Ercole and whose court was famous as a cultural and music center. Obrecht remained in Ferrara and a couple of months later yet another outbreak of the plague caught up with him; he died on August 1st of 1505. He wasn’t even 50 years old.

It is usually assumed that the more famous Josquin had influenced the music of Obrecht. It’s probably not so: much of Josquin’s mature work was written after 1505 (Josquin lived till 1521). The music of Johannes Ockeghem, on the other hand, did affect Obrecht’s compositional style. You can listen to three more pieces by Obrecht. The first one is Kyrie from his Missa Fortuna Desperata. It’s performed by the Anglo-German ensemble The Sound and the Fury (here). The second and the third pieces are the identically named motets, Salve regina. The first one is for four voices (here), and the second, an absolutely magnificent one – for six voices (here). Both are performed by the Oxford Camerata, Jeremy Summerly conducting.

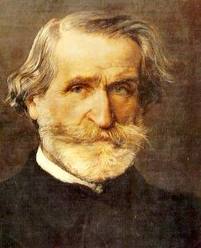

PermalinkOctober 6, 2014. Verdi and Saint-Saëns. Several composers were born this week, Giuseppe Verdi being the most important one. Verdi was born on October 9th of 1813 and last year we celebrated his centenary, writing about his four immensely popular operas, Rigoletto, La Traviata, Il Trovatore, and Aida. Don Carlos, almost as popular, was one of Verdi’s late operas (as were, for example, Aida and Otello). It was commissioned by the Paris Opera in 1866. Five years earlier, in 1861, following Garibaldi’s expeditions, large parts of Italy were united and Victor Immanuel II was crowned the King of Italy. And earlier in1866 Italy fought another war of independence with Austria-Hungary; it stared badly but thanks to the simultaneous (and utterly disastrous) war that Austria was fighting with Prussia, Italy emerged victorious. Venice was joined with the rest of Italy and the Italian state came into being practically in its modern form. Italian nationalism flourished and Verdi was at the epicenter of it. By then he was the most famous opera composer in Europe and the most famous person in Italy. It’s said that letters addressed just “G. Verdi” were delivered to him without fail. At the end of every performance of his operas, the public would stand up and shout “Viva Verdi!” and then continue celebrating him on the streets.

writing about his four immensely popular operas, Rigoletto, La Traviata, Il Trovatore, and Aida. Don Carlos, almost as popular, was one of Verdi’s late operas (as were, for example, Aida and Otello). It was commissioned by the Paris Opera in 1866. Five years earlier, in 1861, following Garibaldi’s expeditions, large parts of Italy were united and Victor Immanuel II was crowned the King of Italy. And earlier in1866 Italy fought another war of independence with Austria-Hungary; it stared badly but thanks to the simultaneous (and utterly disastrous) war that Austria was fighting with Prussia, Italy emerged victorious. Venice was joined with the rest of Italy and the Italian state came into being practically in its modern form. Italian nationalism flourished and Verdi was at the epicenter of it. By then he was the most famous opera composer in Europe and the most famous person in Italy. It’s said that letters addressed just “G. Verdi” were delivered to him without fail. At the end of every performance of his operas, the public would stand up and shout “Viva Verdi!” and then continue celebrating him on the streets.

The libretto of Don Carlos, which is loosely based on a play by Friedrich Schiller, was written in French. The opera was premiered on March 11, 1867 in the beautiful Salle Le Peletier, which housed the Paris Opera till a fire burned it down in 1873 and the company had to move to the newly built Palais Garnier just a couple blocks away. The story revolves around Don Carlos, Prince of Asturias, whose proposed bride, Elisabeth de Valois, marries the prince’s father, Philip II the King of Spain, instead. As always in Verdi’s opera, there are many additional complications, with Princess Eboli falling in love with Carlos, the heretics being put to death, and the politics of Flanders also playing a role. The opera turned out to be too long, even in Verdi’s own estimation, and he began to paring it down ahead of the premier in Paris. Later the same year Verdi created an Italian version of the Don Carlos (called Don Carlo) for the opera theater in Bologna. This is one of the rare operas that rightfully exist in two different languages. Verdi continued revising Don Carlos and several versions exist in both languages. These days it’s performed more often in Italian, but wonderful French-language recordings exist as well: one, for example, with a phenomenal cast that is headed by Placido Domingo as Carlos, with Katia Ricciarelli as Eizabeth, Lucia Valentini Terrani as Eboli, Leo Nucci as Rodrigue (Rodrigo in the Italian version), Ruggero Raimondi as King Philip II and Nicolai Ghiaurov as the Grand Inquisitor. Luciano Pavarotti as Carlo, Daniela Dessì as Elisabetta and Samuel Ramey as the King, with Riccardo Muti conducting, made a great recording of the Italian version in 1992.

A grand dramatic work, Don Carlos may not be as packed with great arias as, for example, Rigoletto, but it has its share of sublimely beautiful music. Here Samuel Ramey sings Ella giammai m'amò! from Act IV of the famous recording we mentioned above. Riccardo Muti leads the orchestra and the chorus of the Teatro alla Scala, Milan. And here Maria Callas sings Tu che le vanita from Act V in a 1959 concert performance in Hamburg. Send shivers down one’s spine, doesn’t it? Lastly, Carlo Bergonzi as Don Carlo and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau as Rodrigo sing the duet E lui! desso! L'infante!... Dio che nell'alma infondere...from Act II with the London Royal Opera House orchestra under the baton of Georg Solti (here, in a 1965 recording).

Camille Saint-Saëns was also born on the 9th, in 1835 and usually gets a short shift. We promise to write more on him next year. Permalink