Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

This Week in Classical Music: April 21, 2025. Prokofiev and Maderna. Two influential composers were born this week, Sergei Prokofiev and Bruno Maderna. Only 29 years separate them (Prokofiev was born on April 23rd of 1891, Maderna – on April 21st of 1920), about the same age difference that separated Haydn from Mozart, but it’s difficult to think of more different composers. Prokofiev, even if hugely talented, was conservative in his writings; Maderna, on the other hand, was one of the most adventuresome modernist composers of his time. We’ve written about Prokofiev many times, for example here, here, here, and here: you wouldn’t be wrong to surmise that we like Prokofiev a lot. We haven’t missed Maderna (here), but we’d like to add a bit to our previous post. Sometime around 1946, Maderna composed a Requiem. The score was lost and then rediscovered in 2009. Requiem is Maderna’s early piece, mostly tonal in style. Here are two first parts of it titled Requiem (introduction) and Kyrie eleison (Lord have mercy). This recording is from the world premier performance made in 2013 by the Robert-Schumann-Philharmonie and the MDR-Rundfunkchor Leipzig chorus under the direction of Frank Beermann. Maderna wrote many concertos for different instruments, but it seems the oboe was his favorite: he wrote three oboe concertos. Here’s Maderna’s First Oboe Concerto, from 1962-63. The great Heinz Holliger is the soloist; Cologne Radio Symphony Orchestra is led by Gary Bertini.

them (Prokofiev was born on April 23rd of 1891, Maderna – on April 21st of 1920), about the same age difference that separated Haydn from Mozart, but it’s difficult to think of more different composers. Prokofiev, even if hugely talented, was conservative in his writings; Maderna, on the other hand, was one of the most adventuresome modernist composers of his time. We’ve written about Prokofiev many times, for example here, here, here, and here: you wouldn’t be wrong to surmise that we like Prokofiev a lot. We haven’t missed Maderna (here), but we’d like to add a bit to our previous post. Sometime around 1946, Maderna composed a Requiem. The score was lost and then rediscovered in 2009. Requiem is Maderna’s early piece, mostly tonal in style. Here are two first parts of it titled Requiem (introduction) and Kyrie eleison (Lord have mercy). This recording is from the world premier performance made in 2013 by the Robert-Schumann-Philharmonie and the MDR-Rundfunkchor Leipzig chorus under the direction of Frank Beermann. Maderna wrote many concertos for different instruments, but it seems the oboe was his favorite: he wrote three oboe concertos. Here’s Maderna’s First Oboe Concerto, from 1962-63. The great Heinz Holliger is the soloist; Cologne Radio Symphony Orchestra is led by Gary Bertini.

Yehudi Menuhin, one of the greatest violinists of the 20th century, was also born this week, on April 22nd of 1916 in New York. And of course, we’ve written about him before (here, for example). Menuhin’s musicianship was impeccable from the earliest days of his career till the end of it. The same could not be said about his technique. We heard him live in the late 1980s, and it was too late: by then, his technique was shaky, and it overshadowed the overall impression. But when you listen to some of his older recordings, they are wonderful. Here’s one of them, the 1966 live recording of Bach’s Violin and Keyboard Sonata No. 4 in C minor BWV 1017, which Menuhin made with Glenn Gould. Idiosyncratic (no doubt that Gould had something to do with this) but absolutely worth listening to.Permalink

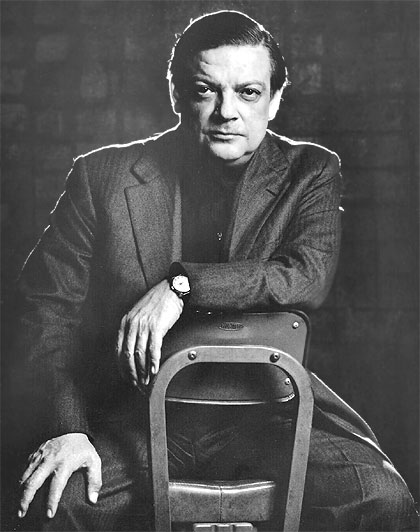

This Week in Classical Music: April 14, 2025. Four Pianists. It has been a long time since we’ve written about the instrumentalists: the city of Naples and composers of note have taken up all of our time. Fortunately, this week presents us with the opportunity to address this problem, as four pianists have their birthdays this week. Two of them were born in the Soviet Union (neither still lives there), and both became famous after winning a Tchaikovsky competition. One is Grigory Sokolov, the other -- Mikhail Pletnev. Sokolov was born to a Jewish father and Russian mother on April 18th of 1950 in Leningrad, now St. Petersburg (we note the nationalities because of the persistent and official policies of antisemitism in the Soviet Union). Sokolov was 16 when, in 1966, he was awarded the first prize among pianists at the Third Tchaikovsky competition. It was quite unexpected (Misha Dichter was the public’s favorite that year), and nobody took Sokolov’s win seriously. Who could imagine then that this youngster would turn into one of the most profound pianists of his generation? For a while, Sokolov’s career didn’t go anywhere, even though he was allowed to play concerts internationally. Sometime around 1988, he left Russia (he’s a Spanish citizen and lives in Italy), and it wasn’t until the 2000s that his career really took off. Since 2006, he has performed only solo concerts; he plays mostly in continental Europe, where he’s famous. Sokolov eschews concerts in the UK and the US because of the visa requirements, which he deems Soviet-like. He rarely makes studio recordings but allows his live concerts to be recorded. Here is one of them, a live recording made in Haydnsaal of the Esterházy Palace in Eisenstadt, Austria, on August 10, 2018. Grigory Sokolov plays Schubert’s Impromptu no. 1 in F minor, from Four Impromptus, Op. 142, D. 935.

all of our time. Fortunately, this week presents us with the opportunity to address this problem, as four pianists have their birthdays this week. Two of them were born in the Soviet Union (neither still lives there), and both became famous after winning a Tchaikovsky competition. One is Grigory Sokolov, the other -- Mikhail Pletnev. Sokolov was born to a Jewish father and Russian mother on April 18th of 1950 in Leningrad, now St. Petersburg (we note the nationalities because of the persistent and official policies of antisemitism in the Soviet Union). Sokolov was 16 when, in 1966, he was awarded the first prize among pianists at the Third Tchaikovsky competition. It was quite unexpected (Misha Dichter was the public’s favorite that year), and nobody took Sokolov’s win seriously. Who could imagine then that this youngster would turn into one of the most profound pianists of his generation? For a while, Sokolov’s career didn’t go anywhere, even though he was allowed to play concerts internationally. Sometime around 1988, he left Russia (he’s a Spanish citizen and lives in Italy), and it wasn’t until the 2000s that his career really took off. Since 2006, he has performed only solo concerts; he plays mostly in continental Europe, where he’s famous. Sokolov eschews concerts in the UK and the US because of the visa requirements, which he deems Soviet-like. He rarely makes studio recordings but allows his live concerts to be recorded. Here is one of them, a live recording made in Haydnsaal of the Esterházy Palace in Eisenstadt, Austria, on August 10, 2018. Grigory Sokolov plays Schubert’s Impromptu no. 1 in F minor, from Four Impromptus, Op. 142, D. 935.

Mikhail Pletnev’s career was very different. He was born in the northern city of Arkhangelsk on April 14th of 1957. He won the Sixth Tchaikovsky Competition in 1974 when he was 21. His piano career flourished immediately after, as he went on tours of Europe and America. He played solo recitals and concerts with Claudio Abbado, Bernard Haitink, Zubin Mehta and other prominent conductors. Pletnev himself started conducting in 1980 while still studying at the Moscow Conservatory. In 1988 he met Mikhail Gorbachev, then the General Secretary of the Communist Party, in Washington, DC; two years later, Gorbachev helped him found the first non-state-owned orchestra, the Russian National Orchestra (RNO). Pletnev made it into one of the best orchestras in Russia. In 2022, after Russia invaded Ukraine, Pletnev made several anti-war comments, after which Putin’s officials pushed him out of his own orchestra. In the aftermath, Pletnev created a new ensemble, the Rachmaninoff International Orchestra; 18 musicians from the RNO joined it. Like Sokolov, Pletnev left Russia in the 1990s: he has been living in Switzerland since 1996. Here’s a recording, made live, like the one we heard from Sokolov. This one was made in Warsaw in August of 2017. Pletnev plays Rachmaninov’s Prelude in G-sharp minor op. 32, no. 12.

Two other pianists born this week are Murray Perahia, one of our all-time favorites; he was born on April 19th of 1947 and the great Artur Schnabel, born April 17th of 1882. We’ve written about Schnabel but not Perahia, which we hope to do in the future. Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: April 7, 2025. Musical Writings and Missed Dates. It happens to us often: we miss an important date, attempt to catch up, and in the process, miss other anniversaries. That’s what happened last week: as we celebrated Pierre Boulez, something we should’ve done two weeks ago, we missed several important birthdays: Franz Josef Haydn’s, Sergei Rachmaninov’s and Alessandro Stradella’s. Haydn, born on March 31st of 1732, is one of our favorite composers, but we feel that he was recently pushed to the periphery of the musical world, quite undeservedly, as we think he firmly belongs in the very center of it. We love his piano sonatas and think that some of them are at least as good as Mozart’s, if not better. He practically invented the genre of the string quartet, and his symphonies (which, to a large extent, were also his invention) are great. It seems he became a better symphonist as he got older: some of his best ones belong to the last cycle of symphonies called “London,” from number 93 to 104. Haydn finished it in 1795, when he was 63, an advanced age for the 18th century. Here is Haydn’s Symphony No. 103, Drumroll. Herbert von Karajan conducts the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra.

Alessandro Stradella was one of the finest Italian composers of the second half of the 17th century. He also led a very turbulent and colorful life, which could’ve served as a basis for a TV series, so full it was of seductions and murders. That, and his talent, deserves a separate entry, which we promise to write. A bit of mystery surrounds his birthday. Grove Music says that Stradella was born on April 3rd of 1639 in Nepi, near Viterbo. Britannica says it was 1642, without providing any specifics. And Wikipedia believes that he was born in Bologna, on June 3rd of 1643. Both Wiki and Grove state that he was born into a noble family, but they differ in their origins. Without knowing any better, we’ll go with Grove.

without providing any specifics. And Wikipedia believes that he was born in Bologna, on June 3rd of 1643. Both Wiki and Grove state that he was born into a noble family, but they differ in their origins. Without knowing any better, we’ll go with Grove.

Today is the birthday of Charles Burney, a minor composer and an influential writer on music, who was born in Shrewsbury, a town in the West Midlands region of England, in 1724. His father was a musician and dancer, and Charles studied music as a boy. At the age of 20, he became an apprentice to the composer Thomas Arne, now remembered mostly for his song Rule, Britannia. Arne connected Burney with Handel, in whose orchestras Burney played several times. In 1746, Burney met Fulke Greville, a rich aristocrat who made Burney his musical companion. Burney spent three years in Greville’s retinue but then left to marry one Esther Steep. They lived in London, where Burney became part of the cultural community, which included the painter Joshua Reynolds (who painted Burney’s portrait, above), Samuel Johnson, a poet and playwright famous for his Dictionary, and Edmund Burke, a statesman and politician. For many years, Burney contemplated writing a book on the history of music. While in London, Burney played the organ, taught music to fashionable people, and composed incidental music for popular plays. In 1751, after falling ill, he and his family moved to King’s Lynne, where they stayed for nine years and where Burney worked as an organist. When he returned to London, his influential friends helped him to reestablish his career in the theater (he collaborated with the great actor and producer David Garrick) and as a teacher.

In 1770, Burney traveled to France and Italy, where he met the young Mozart and, upon return, published a book, The Present State of Music in France and Italy. Then, in 1772, he went to Germany and the Netherlands and wrote a book about the music of those countries. This was the beginning of Burney's literary career, his claim to fame, which we’ll explore further next week. Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: March 31, 2025. Pierre Boulez. Last week we were preoccupied with Naples and missed a very important date: March 26th was the 100th anniversary of Pierre Boulez’s birth. It is hard to overestimate Boulez’s importance in the development of moder music in the second half of the 20th century (we can only think of Karlheinz Stockhausen and maybe Bruno Maderna being on the same level). Grove Music writes: “Resolute imagination, force of will, and ruthless combativeness secured him, as a young man, a position at the head of the Parisian musical avant garde.” But it was not just the Parisian avant-garde that he conquered, it was the whole musical word that he reigned for at least 30 years, from the early 1950s to the early 1980s.

of Pierre Boulez’s birth. It is hard to overestimate Boulez’s importance in the development of moder music in the second half of the 20th century (we can only think of Karlheinz Stockhausen and maybe Bruno Maderna being on the same level). Grove Music writes: “Resolute imagination, force of will, and ruthless combativeness secured him, as a young man, a position at the head of the Parisian musical avant garde.” But it was not just the Parisian avant-garde that he conquered, it was the whole musical word that he reigned for at least 30 years, from the early 1950s to the early 1980s.

Also this year is the 70th anniversary of the premier of one of Boulez’s most important works, Le Marteau sans maître (The Hammer without a Master). It premiered in June of 1955 in Baden-Baden and the work was met with interest by the listeners and praised by the critics and fellow composers. Even Stravinsky, who wrote very little in the serail mode, was enthusiastic. The piece, despite its difficulty, was then played around the world; Boulez brought it to the US in 1957. Le Marteau sans maître epitomized Boulez’s experimentation with the serialism, which he expanded to include not just the series of pitches, but also the duration, tone color and intensity of each sound. Seventy years later, and you cannot hear this seminal composition being played live. Something happened to classical music. Seventy years is a long period, it’s the time, for example, between the completions of Beethoven’s Ninth and Mahler’s Second symphonies (1824-1894), with the whole Romantic period in between. Both composers were celebrated in 1894, while Boulez almost disappeared from the musical scene. And who are the composers of his stature working today?

Boulez was born in a small town of Montbrison, about 100 km west of Lyon. In his youth his interests were split between the piano and mathematics. Upon leaving Catholic school in 1941 he spent a year in Lyon studying higher math. In 1942 he moved to Paris. Pierre’s father wanted him to attend the Ecole Polytechnique, but instead he went to theParis Conservatory where he studied harmony with Olivier Messiaen. The Paris Conservatory was a very conservative place in those days. Even Messiaen, himself a modern composer of huge talent, didn’t teach Mahler and Bruckner. Later on, Boulez would mention in an interview that at that time in his mind “there were two twins: Mahler, Bruckner.” In the same interview he said that “German music stopped at Wagner,” so the Second Viennese School wasn’t taught at all. Boulez learned about atonal music from René Leibowitz, a student of Arnold Schoenberg. He had already felt the need to expand his music language and immediately adopted the new techniques. A year later, in 1945, the young Boulez wrote his first atonal piece of music, a set of twelve Notations for piano. He also wrote two piano sonatas, the second one, large in scale, published in 1950. His music was performed by the pianists Yvette Grimaud and Yvonne Loriod (at that time, Messiaen’s wife), but it was the circulation of the scores among musicians that brought Boulez fame among avant-garde musicians. In 1952 Loriod performed the sonata in Darmstadt to great acclaim. Thus started Boulez’s association with a group of tremendously talented and adventuresome composers and theoreticians that became known as the Darmstadt School. Darmstadt Summer Courses for New Music were held from the early 1950s to 1970. Every other year young musicians gathered in the city to present and discuss their music. Formal courses were taught both in composition and interpretation. Even the abridged list of the attendees looks very impressive: in addition to Boulez, there was Bruno Maderna, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Luigi Nono, Luciano Berio, György Ligeti, John Cage – composers who shaped the music of the second half of the 20th century. Philosophers and critics such as Theodor Adorno, presented their ideas. It was around that time that Boulez came up with his famous aphorism: “Any musician who has not felt … the necessity of the dodecaphonic language is OF NO USE.” In 1952 he wrote a seminal piece, “Le Marteau sans maître” (The hammer without a master) for voice and six instruments. Still difficult, even after half a century of music development, it could be heard here. Pierre Boulez conducts a small ensemble consisting of the flute, the guitar and several percussion instruments. Jeanne Deroubaix is the contralto. The period between 1950s and 1970s was the most productive for Boulez as a composer. In the following years he continued to write but dedicated much time to reworking some of the compositions of the earlier period.

In 1970 President Georges Pompidou, bound to create a cultural legacy, asked Boulez, who was spending most of his time outside of France, to create an institute dedicated to research in music. The result was the IRCAM (Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique, or Institute for Research and Coordination Acoustic/Music). It was set in a building next to the Center Pompidou. With the addition two years later of the Ensemble InterContemporain, IRCAM became a major research and performing center for avant-garde music.

Boulez started conducting in 1957. First it was mostly his own music and that of his young colleagues, but eventually he expanded his repertoire to Stravinsky, Debussy, Webern and Messiaen. In the late 50’s he became the guest conductor of the Southwest German Radio Symphony Orchestra and took residence in Baden-Baden, to a large extent in protest to the conservativism of the French musical culture (that was before the IRCAM). A big break came in 1971 when he was, rather unexpectedly, hired by the New York Philharmonic. During the following years he conducted every major orchestra, expanding his repertoire to include most of the classics (though he never conducted either Tchaikovsky or Shostakovich). Boulez became one of the greatest interpreters of Debussy; we also love his Mahler. Here’s a tremendous interpretation of the 4th movement (Adagio. Sehr langsam und noch zurückhaltend) of Mahler’s Symphony no. 9 with the Chicago Symphony at its best.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: March 24, 2025. Naples. Last week we promised to get back to the music-related impressions of our recent travels. We should state upfront that they were somewhat disappointing. Classical music is not being played in Italy as often as one would hope (and expect), either live in concerts or on the radio. Of all the cities we visited, the one with the richest musical tradition was Naples. Naples is a very old city, going back to the Greek settlement in the 6th century BC, but the history of classical music is much shorter, so those two intersect in the Kingdom of Naples in the 15th century when the King’s chapel had more musicians than any other court in Italy. That was also the time when Tinctoris, a famous composer and music theoretician, stayed with the court. Early in the 16th century, the Aragonese Spanish took over Naples and made it a viceroyalty. Carlo Gesualdo, Price of Venosa, stayed at the court and influenced generations of Neapolitan musicians. The talented Giovanni de Macque was one of them. The Royal Chapel and several major churches were important musical centers; then, in the mid-16th century, the first Conservatory was created. Initially, it was a shelter for orphans where music was one of the subjects taught to children. Eventually, music became the most important subject, and conservatories (soon there were four) attracted talented teachers. Alessandro Scarlatti taught there briefly, as, sometime later, did Nicola Porpora and Leonardo Vinci.

somewhat disappointing. Classical music is not being played in Italy as often as one would hope (and expect), either live in concerts or on the radio. Of all the cities we visited, the one with the richest musical tradition was Naples. Naples is a very old city, going back to the Greek settlement in the 6th century BC, but the history of classical music is much shorter, so those two intersect in the Kingdom of Naples in the 15th century when the King’s chapel had more musicians than any other court in Italy. That was also the time when Tinctoris, a famous composer and music theoretician, stayed with the court. Early in the 16th century, the Aragonese Spanish took over Naples and made it a viceroyalty. Carlo Gesualdo, Price of Venosa, stayed at the court and influenced generations of Neapolitan musicians. The talented Giovanni de Macque was one of them. The Royal Chapel and several major churches were important musical centers; then, in the mid-16th century, the first Conservatory was created. Initially, it was a shelter for orphans where music was one of the subjects taught to children. Eventually, music became the most important subject, and conservatories (soon there were four) attracted talented teachers. Alessandro Scarlatti taught there briefly, as, sometime later, did Nicola Porpora and Leonardo Vinci.

Opera played a very important part in the musical life of Naples. The genre was invented in the early 17th century in northern Italy, Venice in particular, and by midcentury Naples had regular performances of operas by Claudio Monteverdi, Francesco Cavalli and others. Till 1737, the main venue was the San Bartolomeo Theater, when the grand San Carlo Theater was inaugurated (San Bartolomeo was eventually converted into a church). The main figure in the history of the Neapolitan opera was, without a doubt, Alessandro Scarlatti, who lived in the city from 1679 to 1721 and composed more than one hundred operas, of which 70 are extant. With the construction of San Carlo, Naples turned into one of the most important opera centers in Italy, with the best companies presenting their shows. Early in the 18th century, a new style was invented in Naples, that of Opera Buffa, or comic opera. The major composers writing in this genre were Vinci, Scarlatti, and the young Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, who was born in 1710 but lived only 26 years. Pergolesi’s La Serva Padrona is regularly staged these days. Many of the operas were written on the libretti of the famous playwright Carlo Goldoni, the best of them by Baldassare Galuppi, Niccolò Piccinni, Giovanni Paisiello and Domenico Cimarosa. Later in the 19th century, Gaetano Donizetti, a Bergamasque by birth, lived in Naples for many years. He was the director of the San Carlo from 1822 to 1838 and presented 17 premiers of his works there, including Lucia di Lammermoor.

Some of the most famous castrati were born or trained in Naples and performed in the operas of Porpora and Scarlatti. Among the best-known are Farinelli, whose real name was Carlo Broschi, and Caffarelli (Gaetano Majorano). Metastasio, one of the greatest opera librettists of all time, had lived in Naples for years.

As vigorous as the musical life of Naples was from the early 17th to the late 19th century, it thinned out by the 20th, at least in its “classical” form. Nonetheless, it left a treasure trove of great music, of which we’ll present a couple of samples. Here’s the achingly beautiful aria Sussurrando il venticello from Alessandro Scarlatti’s Tigrane, which premiered in Teatro San Bartolomeo, Naples, in February of 1715. And here’s the aria Le faccio un inchino from Domenico Cimarosa’s 1792 opera Il matrimonio segreto.

PermalinkThis Week in Classical Music: March 17, 2025. Bach, abbreviated. Our trip is over, but we’re not ready to resume our musical journeys. Of all the places we visited, only one was musically notable – Naples. Next week we’ll write about some composers who lived and worked in the city and made it famous.

notable – Naples. Next week we’ll write about some composers who lived and worked in the city and made it famous.

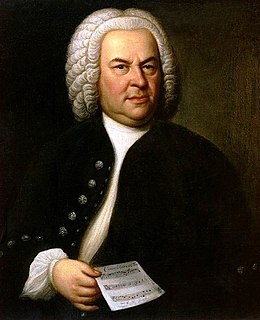

All that said, there is one anniversary that is impossible to miss: Johann Sebastian Bach was born on March 21st of 1685 in Eisenach. What music are we to present to celebrate this event? Out of Bach’s vast and magnificent output, we’ll opt (almost at random) for one clavier piece and an excerpt from one of his grandest creations. The former is French Suite no. 1, performed here by Murray Perahia. The latter, the aria Erbarme dich (Have mercy), from Part 2 of the St. Matthew Passion, is here. The alto is Anne Sofie von Otter, Georg Solti conducts the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.Permalink