Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

November 19, 2012. Last week we celebrated the anniversary of Alexander Borodin but left out two major composers of the 20th century, Aaron Copland and Paul Hindemith. This week is even more prodigious, from Manuel de Falla to Benjamen Britten, Virgil Thomson, and Alfred Schnittke. We’ll start with last week’s birthdays. Aaron Copland was born on November 14, 1900 into a family of recent Russian-Jewish émigrés (his father changed his name from Kaplan), studied in Paris, but became the most "American" of all American composers. His use of hymns and songs, such as the famous rendition of Shakers’ "Simple Gifts" in Appalachian Spring harkens back to the Russian and Czech Nationalist composers, but his musical idiom was very much of the 20th century. Here is At the River, from Old American Songs. It’s performed by the baritone Jonathan Beyer with Jonathan Ware at the piano.

Compared to the lyrical Copland, few composers are more different than the cerebral Paul Hindemith, even though both wrote tonal music and never ventured into the twelve-tone world. Hindemith was born on November 16, 1895 near Frankfurt am Main. He played violin and viola, and started composing at the age of 21. Hindemith’s compositional career blossomed during the time Nazis were in power, and their relationship was complex. Some Nazis despised Hindemith’s music, but other wanted to make him into a model German composer and ambassador of German culture. Hindemith emigrated to Switzerland and then to the US in 1940. In the US he taught at Yale; among his students were Lucas Foss, Normal Dello Joio, and many other. Here is Hindemith’s Viola Sonata Op. 11 No. 4. It is performed by Yura Lee and Timothy Lovelace.

Benjamin Britten was the greatest British composer of the 20th century and probably the first great British composer since Henry Purcell, or Handel, depending on whether the latter is counted as a German composer or an English one (our apologies to the devotees of Elgar, Delius and Vaughan Williams!). He was born on November 22, 1913. When he was 17 he entered the Royal College of Music, where he studied with composers John Ireland and Arthur Benjamin. He started composing around that time. In 1936 he met the tenor Peter Piers who strongly affected Britten’s musical development and also became his lifelong partner. Britten and Pears moved to the US in 1939 (both were conscientious objectors), but returned to Britain in 1942. Britten’s greatest work was in opera: Peter Grimes (1945) made him a star, and altogether he wrote 13 operas, Billy Bud, The Beggar’s Opera and The Turn of the Screw being among the most popular. We don’t have Britten’s operas, but we do have a wonderful song cycle, A Charm of Lullabies, Op. 41 (here). It is sung by the mezzo-soprano Jennifer Johnson with Scott Gilmore at the piano. On a much lighter note, the late Dudley Moore’s parody of Pears singing the supposedly Britten’s rendition of Little Miss Muffet is hilarious and absolutely ingenious (you can find it on YouTube).

first great British composer since Henry Purcell, or Handel, depending on whether the latter is counted as a German composer or an English one (our apologies to the devotees of Elgar, Delius and Vaughan Williams!). He was born on November 22, 1913. When he was 17 he entered the Royal College of Music, where he studied with composers John Ireland and Arthur Benjamin. He started composing around that time. In 1936 he met the tenor Peter Piers who strongly affected Britten’s musical development and also became his lifelong partner. Britten and Pears moved to the US in 1939 (both were conscientious objectors), but returned to Britain in 1942. Britten’s greatest work was in opera: Peter Grimes (1945) made him a star, and altogether he wrote 13 operas, Billy Bud, The Beggar’s Opera and The Turn of the Screw being among the most popular. We don’t have Britten’s operas, but we do have a wonderful song cycle, A Charm of Lullabies, Op. 41 (here). It is sung by the mezzo-soprano Jennifer Johnson with Scott Gilmore at the piano. On a much lighter note, the late Dudley Moore’s parody of Pears singing the supposedly Britten’s rendition of Little Miss Muffet is hilarious and absolutely ingenious (you can find it on YouTube).

We’ll get back to Falla and Schnittke later, in the mean time enjoy the music.

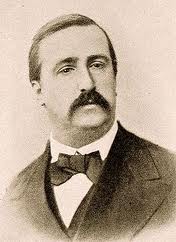

PermalinkNovember 12, 2012. Borodin and more. Alexander Borodin, a Russian composer and famous chemist, was born on this day in St-Petersburg in 1833. He was an illegitimate son of a Georgian prince Luka Gedevanishvili, who had him registered as a son of one of his serfs, Porfiry Borodin. Thus, Alexander Lukich Gedevanishvili was transformed into Alexander Porfirievich Borodin. Alexander received a good education, and took some music lessons (that he was gifted became clear very early on – when he was nine he composed several small pieces), but at the age of 10 he fell in love with chemistry. At 17 he entered the prestigious Medico-Surgical Academy and upon graduating pursued a career of surgeon and chemist, taking additional studies in Heidelberg and in Italy. In 1862, Borodin became a professor of chemistry at the same Academy and taught chemistry there for the rest of his life. His research in chemistry was significant and he became one of the most respected scientists in Russia; the famous Mendeleev, the inventor of the periodic table, was his good friend and colleague. All along, music was a love and a hobby to Borodin, second in priority. The same year he became a professor at the Academy, Borodin met the composer Mily Balakirev and stared taking composition lessons with him. His First Symphony, written in 1867, is not performed often, but the Second one (“Bogatyr”), became very popular. In 1879 he wrote the String Quartet no. 1, two years later, the Second String quartet. Borodin worked on his main composition, the opera Prince Igor, for 18 years. It still wasn’t finished at the time of his premature death on February 27, 1887, at the age of 53. Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Alexander Glazunov completed the opera and the orchestration based on the materials left after Borodin’s death. The opera was first performed in 1890 at the Mariinsky Theater in St-Petersburg to great acclaim. It remains his masterpiece and one of the best known and loved Russian operas.

son of one of his serfs, Porfiry Borodin. Thus, Alexander Lukich Gedevanishvili was transformed into Alexander Porfirievich Borodin. Alexander received a good education, and took some music lessons (that he was gifted became clear very early on – when he was nine he composed several small pieces), but at the age of 10 he fell in love with chemistry. At 17 he entered the prestigious Medico-Surgical Academy and upon graduating pursued a career of surgeon and chemist, taking additional studies in Heidelberg and in Italy. In 1862, Borodin became a professor of chemistry at the same Academy and taught chemistry there for the rest of his life. His research in chemistry was significant and he became one of the most respected scientists in Russia; the famous Mendeleev, the inventor of the periodic table, was his good friend and colleague. All along, music was a love and a hobby to Borodin, second in priority. The same year he became a professor at the Academy, Borodin met the composer Mily Balakirev and stared taking composition lessons with him. His First Symphony, written in 1867, is not performed often, but the Second one (“Bogatyr”), became very popular. In 1879 he wrote the String Quartet no. 1, two years later, the Second String quartet. Borodin worked on his main composition, the opera Prince Igor, for 18 years. It still wasn’t finished at the time of his premature death on February 27, 1887, at the age of 53. Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Alexander Glazunov completed the opera and the orchestration based on the materials left after Borodin’s death. The opera was first performed in 1890 at the Mariinsky Theater in St-Petersburg to great acclaim. It remains his masterpiece and one of the best known and loved Russian operas.

Borodin’s name was given to one of the most unique ensembles, the Borodin Quartet. It is probably the oldest continuously performing quartet in modern history. The quartet was formed in 1944 by the students of Moscow Conservatory. Mstislav Rostorpovich was the first cellist, but very soon he withdrew and Valentin Berlinsky took his place. Rudolf Barshai was the original viola player; he later founded the Moscow Chamber Orchestra. The quartet first performed publicly in 1946 under the name of the Moscow Philharmonic Quartet. It became known as the Borodin Quartet in 1955, Borodin of course being the founder of the Russian quartet tradition. For many years the Quartet worked very closely with the composer Dmitry Shostakovich, whom they first met in 1946; all of Shostakovich’s quartets were in their repertory. Also, they often performed with the great pianist Sviatoslav Richter. Valentin Berlinsky, the cellist, performed continuously from 1944 to 2007, for an amazing 62 years; he died just one year later at the age of 83.

We’ll hear the 3rd movement of Borodin’s quartet no. 2, Notturno, performed by the Borodin Quartet and recorded in 1965 (here, courtesy of YouTube).

Two prominent 20th century composers were also born this week: Aaron Copland, on November 14, 1900, and Paul Hindemith on November 16, 1895. We’ll present them at a later date.

PermalinkNovember 5, 2012. François Couperin, or Couperin le Grand, the great French Baroque composer, was born in Paris on November 10, 1668 during the reign of Louis XIV the Sun King. François was born into a family of musicians (his uncle was a famous composer of his day). His talents became apparent from a very early age. His father was his first music teacher, and he inherited the position of the organist of the church of St-Gervais after his father’s death. The church, not far from the Hôtel de Ville, is one of the oldest in Paris, and the organ that Couperins played is still there today. In 1717 he entered the service of Louis XIV as an organist and composer. Even though his major works were written for the harpsichord, he was never given the title of the harpsichordist to the King. At the court, he gave weekly concerts, mostly of his own music: the “suites” for string and wind instruments and the harpsichord.

His talents became apparent from a very early age. His father was his first music teacher, and he inherited the position of the organist of the church of St-Gervais after his father’s death. The church, not far from the Hôtel de Ville, is one of the oldest in Paris, and the organ that Couperins played is still there today. In 1717 he entered the service of Louis XIV as an organist and composer. Even though his major works were written for the harpsichord, he was never given the title of the harpsichordist to the King. At the court, he gave weekly concerts, mostly of his own music: the “suites” for string and wind instruments and the harpsichord.

As we mentioned, Couperin’s major works were written for the harpsichord. In 1717 he published L'art de toucher le clavecin (The Art of Playing the Harpsichord). He wrote it to instruct musicians in harpsichord playing so that they could perform, among other things, his own compositions. Here is the famous Le Tic-Toc-Choc, from Book III of Pièces de clavecin, transcribed to the modern piano. It is performed – insanely fast – by the Hungarian piano virtuosos Geroges Cziffra (a live recording from his recital in Strasbourg 19 June 1960, courtesy of YouTube). Some listeners believe that he plays too fast but we think there’s enough music left to make it very interesting. Altogether Couperin published four books of harpsichord music, 230 pieces altogether. This music influenced Johann Sebastian Bach, and, much later, Richard Strauss, who in 1940 wrote a charming Divertimento for small orchestra (after François Couperin's keyboard works), Op. 86. Le Tic-Toc-Choc is there, of course, as elegant in this chamber arrangement as it is in the original. For Maurice Ravel Couperin was also a major figure, so much so that he wrote a piano suite Le tombeau de Couperin (Couperin's Memorial). It’s performed here by the pianist Alon Goldstein.Permalink

October 29, 2012. Bellini and more. Vincenzo Bellini was born on November 3, 1801 in Catania, Sicily. It’s said that he was a child prodigy: started studying music at the age of two, playing piano at three, and composed his first pieces at the ago of six.

We don’t have many recordings from the Bellini’s operas for the same reason we’re poor on Verdi or Donizetti. But we do have a fantasy by Franz Liszt called Reminiscences of Norma by Bellini. Liszt’s birthday was last week, and we’re glad to have a chance to acknowledge it. Liszt wrote this paraphrase 10 years after the premier of Norma and used, in a very free form, seven themes from the opera. It’s performed here by the Canadian pianist Janice Fehlauer.

PermalinkOctober 22, 2012. Bizet, Liszt, Scarlatti, Paganini. This week yet again we commemorate the anniversaries of several extraordinary composers: Franz Liszt was born on October 22, 1811, Georges Bizet on October 25, 1838, Domenico Scarlatti on October 26, 1685 and Niccolò Paganini on October 27, 1782. Last year we celebrated Liszt’s 200th anniversary with a detailed account of his life. We’ve written about Paganini and Scarlatti on more than one occasion. Now we’ll focus on Georges Bizet.

Bizet would not live to see the success that Carmen would eventually become. After only its thirty-third performance, Bizet died suddenly from heart disease. Before his death, however, he had signed a contract to stage Carmen at the Vienna Court Opera. The Vienna production became the impetus for Carmen’s success. The opera won praise from both Richard Wagner and Johannes Brahms. Within three years, Carmen appeared in Brussels, London, New York and St. Petersburg. After winning the international stage, Carmen triumphantly returned to Paris in 1883.

Here is Carmen Fantasy, a piece by Franz Waxman based on the themes from Carmen. It’s performed by Irmina Trynkos, violin and Giorgi Latsabidze, piano. And here is the final scene from Carmen, sung in Russia by the mezzo Lidiya Zakharenko and the tenor Zurab Andjaparidze. Vladimir Fedoseev conducts the Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra.

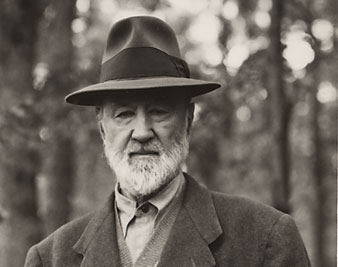

PermalinkOctober 15, 2012. Ives and Flynn. The first internationally acclaimed American composer, Charles Ives was born on October 20, 1974 in Danbury, Connecticut. His father, George, was an Army bandleader, and when Charles was young he listened to the bands practicing in the town square and later played drums in his father’s band. He also learned to play piano and the organ, which apparently he did very well. One might not expect a bandleader to encourage musical experimenting, but that’s just what George Ives did when he taught music to his son. At the age of 14 Charles became a church organist, then moved to New Haven, and eventually entered Yale University. There he wrote his 1st Symphony, although he probably spent as much time playing sports as studying music – he was an excellent athlete. Upon graduating from Yale, Ives joined an insurance company. When it went broke, he and his friend started their own, Ives & Myrick. A successful executive, Ives became well known within the industry and even wrote articles on aspects of the insurance business. Composing music was what he did in his spare time. In 1906 Ives wrote the first of his acknowledged masterpieces, The Unanswered Question, scored for trumpet, four flutes, and string orchestra, a very unusual but highly effective combination of instruments; Ives indicated that the strings should be positioned behind the stage, the flute on the stage, and the trumpet, the one “asking the questions,” in hall itself. In 1908 Ives and his newly wed wife moved to New York; he lived there for the rest of his life. The period from about 1908 to 1927 was very productive: Ives wrote the Concord Sonata, his most popular piano solo composition, several symphonies, including the one titled New England Holidays and the very successful Fourth. He also wrote string quartets, violin sonatas, and songs. Then, abruptly, one day in 1927 he told his wife that he could not compose any longer. From that moment on he didn’t composed another single original tune, though he continued revising his older compositions. He lived another 27 years and died at the age of 80.

bands practicing in the town square and later played drums in his father’s band. He also learned to play piano and the organ, which apparently he did very well. One might not expect a bandleader to encourage musical experimenting, but that’s just what George Ives did when he taught music to his son. At the age of 14 Charles became a church organist, then moved to New Haven, and eventually entered Yale University. There he wrote his 1st Symphony, although he probably spent as much time playing sports as studying music – he was an excellent athlete. Upon graduating from Yale, Ives joined an insurance company. When it went broke, he and his friend started their own, Ives & Myrick. A successful executive, Ives became well known within the industry and even wrote articles on aspects of the insurance business. Composing music was what he did in his spare time. In 1906 Ives wrote the first of his acknowledged masterpieces, The Unanswered Question, scored for trumpet, four flutes, and string orchestra, a very unusual but highly effective combination of instruments; Ives indicated that the strings should be positioned behind the stage, the flute on the stage, and the trumpet, the one “asking the questions,” in hall itself. In 1908 Ives and his newly wed wife moved to New York; he lived there for the rest of his life. The period from about 1908 to 1927 was very productive: Ives wrote the Concord Sonata, his most popular piano solo composition, several symphonies, including the one titled New England Holidays and the very successful Fourth. He also wrote string quartets, violin sonatas, and songs. Then, abruptly, one day in 1927 he told his wife that he could not compose any longer. From that moment on he didn’t composed another single original tune, though he continued revising his older compositions. He lived another 27 years and died at the age of 80.

We have two piano pieces by Ives, Song Without (Good) Words (here) and Some South-Paw Pitching (here), performed by Heather O'Donnell, an American pianist living in Berlin. Heather O’Donnell is a big proponent of contemporary music. To some extent she is a link to our next composer, George Flynn: in 2004 she organized a project, "Responses to Charles Ives," which commissioned seven composers to write piano works. Each composition was supposed to reflect Ives’ influence; one of the contributors was George Flynn with Remembering. Flynn says that in his youth he was greatly influenced by Charles Ives’s Concord piano sonata. Recently, Southport Records issued a CD titled String Fever with three compositions by Flynn. One of them is Together, a 27-minute continuous work for violin and piano. Flynn describes it as developing through a series textures and moods, from quiet to more "aggressive," "jubilant," then moving to "floating serenity" and on. The final sounds of Together return to the opening statement and "can thus serve to restart the piece." This composition was originally written for the violinist Eugene Gratovich, a student of Jascha Heifetz and a big supporter of contemporary music. In this recording Together is performed by the violinist Stefan Hersh with the composer at the piano. You can listen to it here.

Permalink