Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

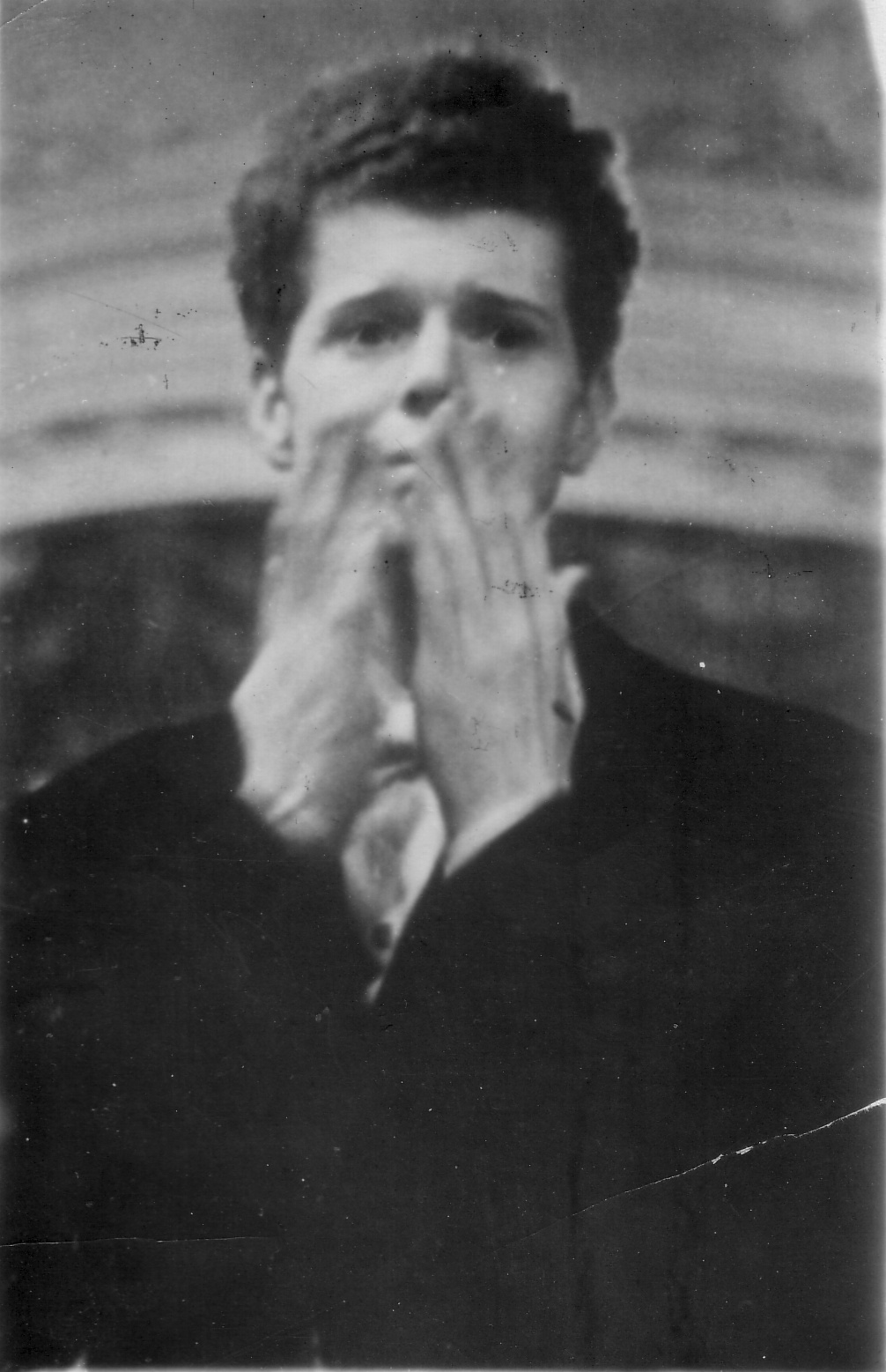

March 11, 2013. Van Cliburn may have been more of a pianist than a musician, and a cultural phenomenon above all, but he affected the lives of millions of people, and that alone has secured him a unique place in the musical Pantheon. His recordings of Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto and Rachmaninov’s Third are among the very finest; and even though his name won’t be mentioned in the same breath as Rubinstein, Richter, Horowitz, Michelangeli or Brendel’s, his death on February 27, 2013 of bone cancer was an event that made the front pages of all the major newspapers and news channels around the world.

Rachmaninov’s Third are among the very finest; and even though his name won’t be mentioned in the same breath as Rubinstein, Richter, Horowitz, Michelangeli or Brendel’s, his death on February 27, 2013 of bone cancer was an event that made the front pages of all the major newspapers and news channels around the world.

When Cliburn came to Moscow in the spring of 1958, he was an acknowledged talent with a sputtering career. He studied with Rosina Lhévinne at the Juilliard, receiving a diploma in 1954. That year he won the prestigious Leventritt competition, which earned him an appearance at the Carnegie Hall. But the mid-1950s also witnessed the ascent of an extraordinary group of young American pianists: Leon Fleisher, Byron Janis, Daniel Pollack, John Browning, Gary Graffman. And of course Arthur Rubinstein, though in his mid-60s, was still playing exceptionally well (Vladimir Horowitz was on one of his famous hiatus). All in all, a difficult time to start a major career. It was Rosina Lhévinne who suggested that her former pupil enter the first international Tchaikovsky competition. Ms. Lhévinne graduated from the Moscow Conservatory with the Gold Medal, and so did her future husband Josef; both studied with Vasily Safonov. They emigrated from Russia before the First World War and eventually settled in New York. In America, Josef Lhévinne, who by all accounts possessed a prodigious technique, had a small career as a concert pianist, but preferred to teach at the Juilliard. Rosina worked as his assistant, and took over his class after Josef‘s death. It became one of the most celebrated in the history of Juilliard.

As Cliburn later said in one of his interviews, he thought his prospects going to the Tchaikovsky competition were not very good, as he expected a Soviet pianist to win. So did the Soviet musical establishment. In a country where classical music occupied a very special place, both socially and politically, and successful musicians were feted by the State, the first international competition was an event of great magnitude. Its results were not to be taken lightly. The country was represented by several established, first-rate pianists, Lev Vlasenko and Naum Shtarkman among them (Shtarkman was already 30, older than the maximum allowed age, but organizers let him participate nonetheless). Cliburn played well during the first round and was admitted to the second; word about the talented American with Russian musical roots started spreading around Moscow.

He played his second round program, which included Chopin’s Fantasy in F minor, Op. 49 and Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody no. 12, brilliantly. Sviatoslav Richter, a member of the piano jury, gave Cliburn 25 points, the highest mark. (The jury itself was spectacular: Emil Gilels was the Chairman, and among the members were Henrich Neuhaus, Dmitry Kabalevsky, Lev Oborin, and Carlo Zecchi). By the third, and final round, Cliburn was the clear favorite not only of the jury but of the public as well. To appreciate the excitement the Competition generated in Moscow, one has to remember the atmosphere of 1958. It was just five years since Stalin’s death. The Russian society, shut down behind the Curtain and traumatized by the terror of the previous 40 years, was opening up, just a bit, during Khrushchev’s “thaw.” People were yearning for new things, and the gangly, 6-foot-4, smiling and irresistibly charming American, who for an average Muscovite looked like an alien, perfectly personified these desires.

The final round was a triumph. The requisite Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov’s Third were spectacular. When Cliburn finished, the public was on its feet, screaming “winner, winner.” In a highly unusual move, Gilels, the jury chairman, went backstage to congratulate him. Richter called him a genius, adding that he does not use the term lightly. Giving the first prize to an American required Khrushchev’s consent, but the premier, charmed as everybody else, approved. The post-competition concerts in Leningrad and again in Moscow were immensely successful. In the US the win also generated tremendous enthusiasm. Just one year earlier, the US was stunned when the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, thus undermining the idea of American technological superiority, and here was a young Texan, who beat the Russians in the cultural field, probably the only area in which the American psyche was still somewhat unsure of itself. New York welcomed Cliburn with a ticker-tape parade, an event unimaginable these days. Time magazine featured his photo with the caption: “The Texan who conquered Russia.” He made a recording of Tchaikovsky’s First Piano concerto with Kirill Kondrashin for RCA, and it sold more than one million copies, eventually going triple-platinum (apparently, still a record for a recording of a concerto). He went on tour of major American concert halls. But as it turned out the years 1958 and ’59 were the peak of his career. The public, and Sol Hurok, his impresario, wanted him to play the Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov concertos over and over, and Cliburn had to oblige. In his recitals, Cliburn attempted to expand the repertory but was met with criticism. He went back to Moscow in 1960 and 1962; the general public still adored him, but some critics were less than satisfied. The consensus was that while he played some pieces extremely well, (Prokofiev’s Third Piano concerto was one of them) other things worked less successfully, Beethoven in particular. His concert schedule became less active, and by 1978 he dropped off the concert scene.

In the end, it doesn’t matter all that much. Cliburn left us several wonderful recordings, conquered Russia and changed the history of two countries. Here’s the historical 1958 recording of the Tachikovsky First piano concerto in B-flat minor. Van Clibrun, Kirill Kondrashin, RCA Symphony orchestra.

PermalinkMarch 4, 2013. Vivaldi, Ravel, Gesualdo. Antonio Vivaldi was born in Venice on March 4, 1678. One of the greatest and most influential of the Baroque composers, these days he’s mostly known for the ubiquitous set of violin concertos known as The Four Seasons. The prolific Vivaldi, who was also a virtuoso violinist, did write a large number of concertos (by some counts more than 500) for different instruments, most for violin, but also for cello, viola d’amore, and the winds, oboe, flute, recorder, and other. But Vivaldi also wrote around 50 operas, which in his days were very popular. In the 18th century, Vivaldi’s influence spread all over Italy, France, and Germany (Bach transcribed many of his concertos) but soon after his death in 1741 his popularity started waning. Many of his manuscripts were lost, and by the end of the 19th century his music was rarely performed. It’s interesting that Italian fascism was one of the reasons for the rediscovery of Vivaldi: the search for “national roots” in the 1920s and ‘30s led the composer Alferdo Casella, and also Ezra Pound and his mistress Olga Rudge to his music. In 1939 Casella organized a “Vivaldi Week,” which became a milestone; Vivaldi’s music has remained popular ever since.

some counts more than 500) for different instruments, most for violin, but also for cello, viola d’amore, and the winds, oboe, flute, recorder, and other. But Vivaldi also wrote around 50 operas, which in his days were very popular. In the 18th century, Vivaldi’s influence spread all over Italy, France, and Germany (Bach transcribed many of his concertos) but soon after his death in 1741 his popularity started waning. Many of his manuscripts were lost, and by the end of the 19th century his music was rarely performed. It’s interesting that Italian fascism was one of the reasons for the rediscovery of Vivaldi: the search for “national roots” in the 1920s and ‘30s led the composer Alferdo Casella, and also Ezra Pound and his mistress Olga Rudge to his music. In 1939 Casella organized a “Vivaldi Week,” which became a milestone; Vivaldi’s music has remained popular ever since.

For many years Vivaldi worked as an impresario, staging his own operas and also those by his fellow Venetians, for example Albinoni and Galuppi. In the second half of the 20th century Vivaldi’s operas also saw a revival, even if not to the same degree as his orchestral music. Here’s an aria from Farnace, at one time one of his most popular operas, which was premiered in 1727 at the Teatro Sant'Angelo. The young French countertenor Philippe Jaroussky is in the title role. Ensemble Matheus is conducted by it’s founder Jean-Christophe Spinosi. And here is the first aria from Vivaldi motet Nulla in mundo pax sincera. The soprano is Magda Kalmár, with Ferenc Liszt Chamber Orchestra, Sándor Frigyes conducting.

The ever-popular Maurice Ravel was born on March 7, 1875. Here’s La vallée des cloches ("The Valley of Bells") from his piano suite Miroirs (Reflections). The suite was written between 1904 and 1905 and dedicated to Les Apaches, a group of French artists and musicians. Ravel was one of them, as was the pianist who premiered Miroirs, Ravel’s good friend Ricardo Viñes. You’ll hear it in the performance by the Israeli-born pianist Ruti Abramovitch.

Carlo Gesualdo, the prince of Venosa and Count of Conza, was one of the most unusual composers in the history of music. It’s hard to beat the description given to him by Wikipedia: “an Italian nobleman, lutenist, composer, and murderer.” Gesualdo was born on March 8, 1566 in Venosa, in what is now the southern province of Basilicata, then part of the Kingdom on Naples. In 1586 he married his first cousin, Maria d’Avalos, who was several years older than Carlo and already twice-widowed. Two years later Maria began an affair with Fabrizio Carafa, the Duke of Andria. On October 16, 1590, at the Palazzo San Severo in Naples, Gesualdo caught his wife and the duke in flagrante and stabbed both of them to death. That being a crime of passion, Gesualdo was not prosecuted, even though the story was widely reported. The famous poet Torquato Tasso, Gesualdo’s friend until the murder, wrote several sonnets eulogizing the lovers. This episode didn’t prevent Gesualdo from marrying Leonora d'Este, a niece of Duke of Ferrara, in 1596. Gesualdo composed five books of madrigals, music for the Passion, and some instrumental pieces. His music was highly unorthodox, expressive and chromatic to an unusual extent. Even today its modulations prick up listeners’ ears. You can hear it in his setting of O Vos Omnes, performed by the Cambridge Singers, John Rutter conducting (here) or in the madrigal Moro, lasso, al mio duolo (I die, alas, in my suffering) performed by the Deller consort (here).

We mourn the passing of Van Cliburn, who died on February 27 of bone cancer. We’ll dedicate the next entry to this phenomenal pianist.

PermalinkFebruary 25, 2013. Rossini, Chopin, Smetana. Three composers were born this week, Gioachino Rossini, Frédéric Chopin and Bedřich Smetana, Rossini on February 29, 1792, Chopin on March 1, 1810 (there is some confusion regarding the date: the record in the parish register says February 22, but it was entered a couple months after Chopin’s birth, and the family always celebrated his birthday on March 1), and Smetana on March 2, 1824. We’ve written about Rossini before, and Chopin doesn’t need any introductions: he remains one of the most popular composers both with performers (we have more than 300 recordings of his works) and listeners. So in lieu of commemorations, here’s Rossini’s overture to the opera La Gazza Ladra (The Thieving Magpie). According to Rossini himself, it was written on the day of the performance, on May 31, 1817 in Milan, with Rossini locked in a room, throwing pages of completed music through the window for the copyists. If true, we have to acknowledge the professionalism of the musicians of La Scala orchestra, who were able to perform the Overture later that evening site unseen. In this recording it is performed by the Vienna Philharmonic, Claudio Abbado conducting. As for Chopin, here’s Bolero Op 19 from 1833, one of his less frequently performed pieces. Lara Downes is at the piano.

Bedřich Smetana, the "father of Czech music," was born in a small picturesque town of Litomyšl not far from Prague, in Bohemia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. German was the official language of Bohemia, and Czech music, as such, practically didn’t exist (Josef Mysliveček, 1737 – 1781, was born in Prague but wrote Italian opera seria and classical symphonies and spent most of his productive years in Italy. Anton Reicha, 1770 – 1836, was also born in Prague, but lived mostly in Vienna, eventually settling in Paris and becoming a French citizen). At the age of 15, Bedřich was sent to Pague, to the Academic Grammar school. He didn’t fit in there, disliked the school and skipped many classes; instead he attended concerts, operas and even joined an amateur string quartet for which he composed several pieces. He heard Franz Liszt, then at the height of his pianist career, play recitals, and decided that he should become a professional musician (later he and Liszt became close). When his father learned about Bedřich’s truancy, he removed him from the city and placed him in the care of his uncle. Four years later, 19-year old Smetana won his father's approval of his career choice and once again departed for Prague. He recognized the need for formal musical training and took theory and composition lessons with Josef Proksch, then the head of the Prague Music Institute. In the meantime, he earned some money teaching music to the children of a local nobleman. In 1848, the year revolutions swept over Europe, Smetana took part in the uprising aimed to end the rule of the Hapsburgs and afford more autonomy for the Czech lands. The rebellion was put down, but luckily Smetana avoided imprisonment.

and Czech music, as such, practically didn’t exist (Josef Mysliveček, 1737 – 1781, was born in Prague but wrote Italian opera seria and classical symphonies and spent most of his productive years in Italy. Anton Reicha, 1770 – 1836, was also born in Prague, but lived mostly in Vienna, eventually settling in Paris and becoming a French citizen). At the age of 15, Bedřich was sent to Pague, to the Academic Grammar school. He didn’t fit in there, disliked the school and skipped many classes; instead he attended concerts, operas and even joined an amateur string quartet for which he composed several pieces. He heard Franz Liszt, then at the height of his pianist career, play recitals, and decided that he should become a professional musician (later he and Liszt became close). When his father learned about Bedřich’s truancy, he removed him from the city and placed him in the care of his uncle. Four years later, 19-year old Smetana won his father's approval of his career choice and once again departed for Prague. He recognized the need for formal musical training and took theory and composition lessons with Josef Proksch, then the head of the Prague Music Institute. In the meantime, he earned some money teaching music to the children of a local nobleman. In 1848, the year revolutions swept over Europe, Smetana took part in the uprising aimed to end the rule of the Hapsburgs and afford more autonomy for the Czech lands. The rebellion was put down, but luckily Smetana avoided imprisonment.

While Smetana’s earliest compositions were written in 1840, his most accomplished music dates from the 1860s. In 1861, the Habsburg administrations, in an attempt to address the rising nationalism, laid out plans for the Provisional Theater dedicated to Czech opera. Smetana saw it as a chance to create a new genre, following the example of the Russian composer Mikhail Glinka. For that he had to learn the Czech language: the first language of the majority of educated Czechs of the time, and Smetana’s, was German. He composed the first opera, The Brandenburgers in Bohemia, in 1862-63, and based the story in 13th century Prague. It was premiered at the Provisional Theatre in 1866. What then followed was Smetana’s most successful opera, The Bartered Bride. It premiered also 1866, and also at the Provisional Theatre. By then Smetana was appointed the principal conductor of the Theatre. Smetana wrote seven more operas, a large number of piano compositions, some wonderful songs, and several orchestral pieces. Of these Má vlast, a set of six symphonic poems, is the best known. The cycle was written between 1874 and 1879. Here is the second poem, Vltava, sometimes labeled by the German name of the river, Die Moldau, in the performance by the Vienna Philharmonic, Herbert von Karajan conducting (courtesy of YouTube.). According to the composer, the music describes the flow of this beautiful river from its spring in the hills of northern Bohemia, through Prague and other towns, and to the point where it joins the Elbe.

In his late years Smetana suffered from deafness (he losthis hearing completely in 1874) and generally poor health, which didn’t stop him from composing some of his best music. At the end of his life, his mental health deteriorated as well. Smetana died in Prague on May 12, 1884 in a lunatic asylum. His funeral became a national event.

PermalinkFebruary 18, 2013. Boccherini and Handel. For centuries, Italy, and Rome in particular, has attracted the best of composers of the time. Starting with the Renaissance, when Flemish and Spanish musicians practically created Italian music before the Italians got to it, during the Baroque era, and even in the 19th and 20th centuries (take for example the French Prix de Rome), composers from different countries flocked to Rome and Naples. But of course it was not a one-way street, and some Italian composers went to foreign countries: Jean-Baptiste Lully – to France, Domenico Scarlatti – to Spain. And so did Luigi Boccherini. Boccherini was born in Lucca on February 19, 1743. As a young boy he was sent to study in Rome. When he was fourteen, his father took him to Vienna, where they worked in the band of the imperial Burgtheater. In 1761 Boccherini went to Madrid and stayed in Spain for the rest of his life (he died in 1805). One of the best pieces he wrote was the Cello concerto in B flat Major, the ninth of his cello concertos. Boccherini was a talented cellist himself, and composed 12 concertos for this instrument. You can listen to it here (courtesy of YouTube) in the performance by the 22-year old Jacqueline du Pré, with Daniel Barenboim conducting the English Chamber Orchestra (the recoding was made in April of 1967; Barenboim and du Pré married in June of that year in Jerusalem, right after the end of the Six-Day War).

got to it, during the Baroque era, and even in the 19th and 20th centuries (take for example the French Prix de Rome), composers from different countries flocked to Rome and Naples. But of course it was not a one-way street, and some Italian composers went to foreign countries: Jean-Baptiste Lully – to France, Domenico Scarlatti – to Spain. And so did Luigi Boccherini. Boccherini was born in Lucca on February 19, 1743. As a young boy he was sent to study in Rome. When he was fourteen, his father took him to Vienna, where they worked in the band of the imperial Burgtheater. In 1761 Boccherini went to Madrid and stayed in Spain for the rest of his life (he died in 1805). One of the best pieces he wrote was the Cello concerto in B flat Major, the ninth of his cello concertos. Boccherini was a talented cellist himself, and composed 12 concertos for this instrument. You can listen to it here (courtesy of YouTube) in the performance by the 22-year old Jacqueline du Pré, with Daniel Barenboim conducting the English Chamber Orchestra (the recoding was made in April of 1967; Barenboim and du Pré married in June of that year in Jerusalem, right after the end of the Six-Day War).

George Frideric Handel was born February 23, 1685 in Halle, now Germany and back then – Duchy of Mageburg in Brandenburg-Prussia. He settled in England in 1712, becoming a British subject and, eventually, a national composer, but before that he, like so many, traveled to Italy. The year was 1706, Handel was only 21 but already an author of two operas. He arrived in Florence first, but then moved to Rome, where he stayed for four years. He wrote two more operas, Rodrigo and Aggripina. Both were staged outside of Rome, the former in Florence, the latter in Venice: at the time Pope Clement XI banned all opera performances in favor of sacred music. Handel also wrote cantatas and several oratorios. Here’s an excerpt from one of them, the oratorio La resurrezione, written in 1708. It’s performed by the Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra, Ton Coopman conducting (courtesy of youTube).

PermalinkFebruary 11, 2013. Arcangelo Corelli. The Italian composer and violinist was born on February 17, 1653 in a small town of Fusignano, not far from Ravenna. He studied music in the nearby Faenza, better known for its ceramics than music, and then moved to Bologna, which indeed was an important cultural center of the time. Bologna had a famous school of violin playing, and Corelli studied with several noted violinists. It is said that around that time he probably made several trips abroad: to France, where he might have met Jean-Baptiste Lully, and to Germany. He later moved to Rome, where he found several influential patrons, Cardianl Ottoboni and Queen Christina of Sweden being the major ones. He had pupils, some of whom became quite famous as composers, for example Francesco Geminiani and Pietro Locatelli, and many violinists. Corelli’s greatest contribution was in the development of Concerti Grossi. In a concerto grosso the musical interplay happens between a small group of soloists and the full (usually string) orchestra. Corelli’s concerti grossi constitute his famous Opus 6, the first eight compositions of which are designated as “church concertos,” and the following four – as concerti da camera, or chamber concerts. They were not published till 1714, after Corellis’s death, but Georg Muffat, who stayed in Italy in the 1680s, reported to have heard Corelli’s concerti grossi in 1682. One of the best known examples of concerti grossi was written about 60 years later by Handel, also as his opus 6. Corelli’s concerti became very popular throughout Europe, and are often played these days by authentic instruments ensembles. Corelli influenced many composers, Giuseppe Torelli and Antonio Vivaldi more than other. Johann Sebastian Bach studied his work and, copyright not being an issue in the seventeen century, based some of his music on Corelli’s.

and then moved to Bologna, which indeed was an important cultural center of the time. Bologna had a famous school of violin playing, and Corelli studied with several noted violinists. It is said that around that time he probably made several trips abroad: to France, where he might have met Jean-Baptiste Lully, and to Germany. He later moved to Rome, where he found several influential patrons, Cardianl Ottoboni and Queen Christina of Sweden being the major ones. He had pupils, some of whom became quite famous as composers, for example Francesco Geminiani and Pietro Locatelli, and many violinists. Corelli’s greatest contribution was in the development of Concerti Grossi. In a concerto grosso the musical interplay happens between a small group of soloists and the full (usually string) orchestra. Corelli’s concerti grossi constitute his famous Opus 6, the first eight compositions of which are designated as “church concertos,” and the following four – as concerti da camera, or chamber concerts. They were not published till 1714, after Corellis’s death, but Georg Muffat, who stayed in Italy in the 1680s, reported to have heard Corelli’s concerti grossi in 1682. One of the best known examples of concerti grossi was written about 60 years later by Handel, also as his opus 6. Corelli’s concerti became very popular throughout Europe, and are often played these days by authentic instruments ensembles. Corelli influenced many composers, Giuseppe Torelli and Antonio Vivaldi more than other. Johann Sebastian Bach studied his work and, copyright not being an issue in the seventeen century, based some of his music on Corelli’s.

One of the most popular of Corelli’s concerti grossi is number eight, commonly known as “Christmas Concerto.” You can listen to it here, in a decidedly unauthentic but still pleasing performance by the Berlin Philharmonic, Herbert von Karajan conducting (courtesy of YouTube).Permalink

February 4, 2013. Centuries apart: Palestrina and Berg. We missed Giovanni Pierluigi Palestrina’s official birthday by one day: he was probably born on February 3, 1525, but back then church records were not kept very diligently, so we really cannot be sure: other records indicated that he may have been born a year later, on February 2, 1526. One way or another, this is as good a time as any to celebrate this supreme master of Renaissance polyphony. Palestrina’s name refers to the place where he was born, a small ancient town just outside of Rome (the town was a popular summer resort in ancient Roman times and was famous for the magnificent temple of Fortuna). Palestrina went to Rome as a boy and probably started as a chorister at the basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore. He then worked as the organist at several churches and started composing around that time: his first book of Masses was published in1551. It’s interesting to note that till that time, most of the church music performed in Rome was composed by the Franco-Flemish or Spanish composers, such as Guillaume Dufay, Orlando di Lasso, Josquin des Prez and Cristóbal de Morales. Palestrina’s music so impressed Pope Julius III that he made him maestro di cappella of the papal choir at St Peter's, the Cappella Giulia. Later he served as the choirmaster in other famous churches of Rome such as San Giovanni in Laterano and Santa Maria Maggiore, but eventually returned to St-Peters. Palestrina composed a large number of Masses, probably around 100, many madrigals and motets for several voices, from four to twelve. One of his Masses, Missa Papae Marcelli, is famous for saving, it is said, polyphony as art. In the mid-16th century, in reaction to the Reformation, the Catholic Church became concerned with the intelligibility of services, realizing that during Masses parishioners should understand the sacred words, something considered not important in earlier ages. The many-voiced Masses were often unintelligible and the Pope was about to ban them, when, upon hearing Palestrina’s Missa Papae Marcelli, with its beautiful but well-articulated voicing, the Church officials relented and allowed the polyphonic music to continue. The Mass, as its name indicates, was composed in honor of Pope Marcellus II, who reigned for just three weeks in 1555. Here’s Sanctus and Benedictus, performed by The Tallis Scholars, Directed by Peter Phillips.

really cannot be sure: other records indicated that he may have been born a year later, on February 2, 1526. One way or another, this is as good a time as any to celebrate this supreme master of Renaissance polyphony. Palestrina’s name refers to the place where he was born, a small ancient town just outside of Rome (the town was a popular summer resort in ancient Roman times and was famous for the magnificent temple of Fortuna). Palestrina went to Rome as a boy and probably started as a chorister at the basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore. He then worked as the organist at several churches and started composing around that time: his first book of Masses was published in1551. It’s interesting to note that till that time, most of the church music performed in Rome was composed by the Franco-Flemish or Spanish composers, such as Guillaume Dufay, Orlando di Lasso, Josquin des Prez and Cristóbal de Morales. Palestrina’s music so impressed Pope Julius III that he made him maestro di cappella of the papal choir at St Peter's, the Cappella Giulia. Later he served as the choirmaster in other famous churches of Rome such as San Giovanni in Laterano and Santa Maria Maggiore, but eventually returned to St-Peters. Palestrina composed a large number of Masses, probably around 100, many madrigals and motets for several voices, from four to twelve. One of his Masses, Missa Papae Marcelli, is famous for saving, it is said, polyphony as art. In the mid-16th century, in reaction to the Reformation, the Catholic Church became concerned with the intelligibility of services, realizing that during Masses parishioners should understand the sacred words, something considered not important in earlier ages. The many-voiced Masses were often unintelligible and the Pope was about to ban them, when, upon hearing Palestrina’s Missa Papae Marcelli, with its beautiful but well-articulated voicing, the Church officials relented and allowed the polyphonic music to continue. The Mass, as its name indicates, was composed in honor of Pope Marcellus II, who reigned for just three weeks in 1555. Here’s Sanctus and Benedictus, performed by The Tallis Scholars, Directed by Peter Phillips.

Three century after the death of Palestrina, on February 9, 1885 Alban Berg was born in Vienna. One of the three leading composers of the Second Viennese school, he, with Schoenberg and Webern, pretty much transformed our understanding of classical music. Berg started composing when the prevailing trends were those of the late Romanticism. His first piano Sonata, a very formidable opus 1, is written in this style, even though it already contains harmonies that would later develop into the atonal music of his mature period. In 1924 he wrote his first opera, Wozzeck, which became one of the most important compositions of the 20th century. In 1934 - 35 he wrote most of his second opera, Lulu: the first two acts were completed, but Berg managed to finish only parts of the third act. Berg died, impoverished, of blood poisoning at the age of 50, in 1935. One of the reasons he failed to complete Lulu was the break he took from writing the opera to compose a violin sonata. The sonata was a reaction to the death of Manon Groppius, the daughter of his friends Alma Mahler, the former wife of Gustav, and the architect Walter Gropius. Here it is, performed by the violinist Nana Jashvili with the Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra, Jonas Alexas conducting.

Permalink