Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

March 20, 2017. Bach, Hasse and more. Johann Sebastian Bach was born on March 21st of 1685. We hope to be forgiven for not going any further this year (but do see below).

A very different German composer was also born this week. Johann Adolph Hasse, who wrote Italian operas admired both in Italy and in Germany, was born in Bergedorf, near Hamburg. He was baptized on March 25th of 1699. Hasse started his musical career as a singer, but by the age of 22 wrote his first opera, Antioco. The following year he left for Italy. He traveled through Venice, Bologna, Florence and Rome but eventually settled in Naples. There, he met Alessandro Scarlatti, who befriended Hasse and became his teacher. He also met with Nicola Porpora and maybe took some music lessons from him too. Carlo Broschi, known as Farinelli, Porpora’s pupil, was a brilliant castrato singer; Hasse and Farinelli became good friends and eventually Farinelli would premier several of Hasse’s operas. Hasse lived in Naples for seven year, enjoying a highly successful career. In 1730 he went to Venice where his opera Artaserse was performed during the Carnival. Farinelli sung the title role. When Farinelli was in Spain (he became the Chamber musician to King Philip V in 1737 and stayed in Spain for the next 10 years) he sung, on the King’s request, two arias from Act 2, Per questo dolce amplesso and Pallido il sole, every evening. Here’s Per questo, sung by the soprano Vivica Genaux with the Akademie fur Alte Musik Berlin under direction of René Jacobs, and here – Pallido, in an interpretation closer to Farinelli’s, as it’s sung by the countertenor Andreas Scholl. The Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment is conducted by Roger Norrington.

career as a singer, but by the age of 22 wrote his first opera, Antioco. The following year he left for Italy. He traveled through Venice, Bologna, Florence and Rome but eventually settled in Naples. There, he met Alessandro Scarlatti, who befriended Hasse and became his teacher. He also met with Nicola Porpora and maybe took some music lessons from him too. Carlo Broschi, known as Farinelli, Porpora’s pupil, was a brilliant castrato singer; Hasse and Farinelli became good friends and eventually Farinelli would premier several of Hasse’s operas. Hasse lived in Naples for seven year, enjoying a highly successful career. In 1730 he went to Venice where his opera Artaserse was performed during the Carnival. Farinelli sung the title role. When Farinelli was in Spain (he became the Chamber musician to King Philip V in 1737 and stayed in Spain for the next 10 years) he sung, on the King’s request, two arias from Act 2, Per questo dolce amplesso and Pallido il sole, every evening. Here’s Per questo, sung by the soprano Vivica Genaux with the Akademie fur Alte Musik Berlin under direction of René Jacobs, and here – Pallido, in an interpretation closer to Farinelli’s, as it’s sung by the countertenor Andreas Scholl. The Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment is conducted by Roger Norrington.

In 1730 Hasse married Faustina Bordoni, a famous mezzo-soprano, who made her name in London singing in operas of Handel and Bononcini (there, her rivalry with another diva, the soprano Francesca Cuzzoni, was legendary). That same year Hasse and Faustina moved to Dresden, to the lavish court of Augustus II “the Strong,” the Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, where Hasse was given the position of Kapellmeister. Faustina made her debut at the court the day after the couple arrived in Dresden. A year later Hasse wrote Cleofide, an opera based on Metastasio’s original libretto. It was premiered at the Opernhaus am Zwinger, the royal opera house, one of the largest in Europe. Faustina sung the title role. Johann Sebastian Bach, who was then the Thomaskantor in Leipzig, and his son Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach attended the performance. The next day Bach Sr. gave an organ performance in the Sophienkirche, a historic Gothic church that was damaged in 1945 and destroyed later by the GDR rulers (we wrote about the church in one of our entries on Wilhelm Friedemann Bach). C.P.E said later that Johann Sebastian and Hasse were “well acquainted.” Here is Cleofide’s aria Digli ch'io son Fedele, sung by the wonderful English soprano Emma Kirkby. William Christie conducts Cappella Coloniensis.

Hasse’s career was at its zenith, he was immensely popular both in Germany and in Italy, where he was going practically every year. Hasse was still to meet Frederick the Great and make friends with Metastasio. About this and more, some other time.

Béla Bartók, one of the most influential composers of the first half of the 20th century, was also born this week, on March 25, 1881. And Pierre Boulez, extremely influential in the second half of the 20th century, was born on March 26th of 1925.Permalink

March 13, 2017. Hugo Wolf, a wonderful composer of the German Lied, was born today in 1860. He lived a short life, dying of syphilis in 1903; he mentally deteriorated much earlier: his last song was written in 1898. What a scourge it was, syphilis, before the invention of penicillin! Schubert died of it at the age of 31, and so did Schumann, just 46. It is thought that Beethoven’s deafness was brought on by syphilis. Gaetano Donizetti died suffering terribly, Frederick Delius went blind and became paralyzed, and Niccolò Paganini lost his voice, probably of the mercury treatment, which back then was considered a treatment for the terrible disease. The notion of a great composer suffering from syphilis was so common that Thomas Mann made it central in his great novel, Doktor Faustus, but with a literary twist: he had the protagonist, the composer Adrian Leverkühn, strike a bargain with the Devil, the disease as payment for being a genius. Mann studied Wolf’s biography and used some episodes to describe Leverkühn descending into madness.

syphilis, before the invention of penicillin! Schubert died of it at the age of 31, and so did Schumann, just 46. It is thought that Beethoven’s deafness was brought on by syphilis. Gaetano Donizetti died suffering terribly, Frederick Delius went blind and became paralyzed, and Niccolò Paganini lost his voice, probably of the mercury treatment, which back then was considered a treatment for the terrible disease. The notion of a great composer suffering from syphilis was so common that Thomas Mann made it central in his great novel, Doktor Faustus, but with a literary twist: he had the protagonist, the composer Adrian Leverkühn, strike a bargain with the Devil, the disease as payment for being a genius. Mann studied Wolf’s biography and used some episodes to describe Leverkühn descending into madness.

Wolf was born in Duchy of Styria, then part of the Austrian Empire, now in Slovenia. A child prodigy, he started studying two instruments, the piano and the violin, at the age of four. When he was 11 he was sent to a boarding school at the Benedictine abbey of St. Paul in Lavanttal, Carinthia. There he played the organ, performed in a piano trio and studied operas by the Italian bel canto masters and Gounod. In 1875 he moved to Vienna to study at the conservatory. There he composed his first songs and made many friends, one of whom was Gustav Mahler (they were born just three months apart). While in Vienna, Wolf became an avid opera-goer; in 1875 he heard Tannhäuser and Lohengrin, declaring himself a Wagnerian in the aftermath. He met Wagner in December of that year and showed him several compositions; Wagner was supportive but suggested that Wolf write more substantive pieces. His early compositions were noticed in Viennese musical circles and he found several benefactors, which allowed him to compose without having to seek additional income. That was fortunate as Wolf’s temperament made him ill-suited for teaching. As fate would have it, it was one of his patrons, a wealthy but minor composer Adalbert von Goldschmidt, who took Wolf to a brothel for a “sexual initiation”; it’s there that Wolf most likely contracted syphilis. Financial support being tenuous, Wolf tried to earn money as a professional musician, playing violin in an orchestra. That didn’t work out, so eventually he turned to musical criticism. He became known as a passionate writer who could be very hard on some composers (Anton Rubinstein, the author of the opera Demon, was one of his victims).

In 1888 Wolf dropped musical criticism and moved to Perchtoldsdorf, a suburb of Vienna, to a vacation home of a friend. There he immersed himself in composing. Thus commenced the most productive period of Wolf’s life: in 1888 alone he composed more than 90 songs. The two songs that we’ll hear are from that period. Both are performed by the soprano Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, one of the finest interpreters of Wolf’s songs. Here’s Kennst du das Land (Do you know the land), based on Manon’s song from Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister, and here – Nachtzauber, after a poem by the German poet Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff. Gerald Moore is on the piano in both recordings. Wolf continued composing feverishly till 1891, when his habitual depression set in, probably aggravated by the early onset of syphilis. While he stopped composing, his fame grew, especially in Germany. Even Brahms, whom Wolf severely criticized in some of his articles, and therefore was not a big supporter, acknowledged Wolf’s talent. In the following years, Wolf composed an opera, Der Corregidor, based on The three-cornered Hat by Alarcón. It was staged in 1896 with some initial success but soon was dropped, not to be revived to this day. He started another opera, also after Alarcón. called Manuel Venegas but abandoned it after writing just several scenes. By 1898 his madness was obvious. He insisted that he was the music director of the Vienna Opera (Mahler actually was), attempted suicide, after which he was placed into an asylum for the insane. He died there on February 22nd of 1903.Permalink

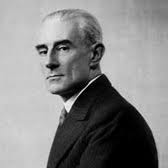

March 6 2017. Ravel and more. The ever popular Maurice Ravel was born on March 7th of 1875. He’s a favorite both with performers (in our library we have about 150 recordings) and with listeners (for the different interpretations of La Valse more so than for any other of Ravel’s compositions). He started as a younger contemporary of Debussy, 13 years his senior, and lived into the era dominated by Stravinsky and Schoenberg. One of Ravel’s first serious pieces was Pavane pour une infante défunte (Pavane for a dead princess), a piano composition written in 1899 while he was still studying at the Paris Conservatory (his composition teacher was Gabriel Fauré). Here it is, played by the American pianist Bill-John Newbrough. In 1910 Ravel created an orchestral version, which can be heard as often as the original piano work. One of the Ravel’s last compositions was a song cycle Don Quichotte à Dulcinée, from 1932-33. It was written on the texts by the writer Paul Morand. Morand, born in 1888, was a good friend of Marcel Proust. Proust was half-Jewish, some of his friend were Jewish but some – anti-Dreyfusards and anti-Semites; unfortunately, Morand belonged to the latter group. In the late 1930s Morand became close to the anti-Semitic Action française, and later, during the War, to the Vichy government. Speaking of Proust, it’s interesting that he admired Debussy (he heard Pelléas et Mélisande several times on his Théâtrophone, an ingenious device that allowed the owner to listen to live opera or theatrical performances over the phone) but practically never mentioned Ravel. One explanation may be that Reynaldo Hahn, a noted composer and one of Proust’s closest friends, was rather critical of Ravel’s work. Here’s Chanson Romanesque from Don Quichotte with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. Karl Engel is on the piano.

Ravel’s compositions). He started as a younger contemporary of Debussy, 13 years his senior, and lived into the era dominated by Stravinsky and Schoenberg. One of Ravel’s first serious pieces was Pavane pour une infante défunte (Pavane for a dead princess), a piano composition written in 1899 while he was still studying at the Paris Conservatory (his composition teacher was Gabriel Fauré). Here it is, played by the American pianist Bill-John Newbrough. In 1910 Ravel created an orchestral version, which can be heard as often as the original piano work. One of the Ravel’s last compositions was a song cycle Don Quichotte à Dulcinée, from 1932-33. It was written on the texts by the writer Paul Morand. Morand, born in 1888, was a good friend of Marcel Proust. Proust was half-Jewish, some of his friend were Jewish but some – anti-Dreyfusards and anti-Semites; unfortunately, Morand belonged to the latter group. In the late 1930s Morand became close to the anti-Semitic Action française, and later, during the War, to the Vichy government. Speaking of Proust, it’s interesting that he admired Debussy (he heard Pelléas et Mélisande several times on his Théâtrophone, an ingenious device that allowed the owner to listen to live opera or theatrical performances over the phone) but practically never mentioned Ravel. One explanation may be that Reynaldo Hahn, a noted composer and one of Proust’s closest friends, was rather critical of Ravel’s work. Here’s Chanson Romanesque from Don Quichotte with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. Karl Engel is on the piano.

When Mozart said that "Bach is the father, we are the children,” he didn’t mean Johann Sebastian Bach, he meant his second son, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. It may be surprising to us, but during Mozart’s time, C.P.E. Bach’s reputation was held in higher esteem than his father’s. Carl Philipp Emanuel, whose second name came from his godfather, Georg Philipp Telemann, was born on March 8th of 1714 in Weimar, where his father served as the organist and Konzertmeister at the court of dukes of Saxe-Weimar. From 1738 and for the following 30 years, Emanuel, as he was known to his contemporaries, served in Berlin at the court of Crown Prince Frederick of Prussia, who in 1740 was crowned as King Frederick II (the Great). Emanuel was allowed to leave in 1768 to succeed his godfather Telemann as music director in Hamburg. In 1769 Emanuel wrote The Israelites in the Desert, an oratorio considered to be his masterpiece. Five years later he wrote another oratorio, Die Auferstehung und Himmelfahrt Jesu (The Resurrection and Ascension of Jesus). The libretto was by one Karl Wilhelm Ramler written in 1760, and that same year the prolific Telemann used it for an oratorio of his own. C.P.E. Bach’s oratorio is not well known, at least not as well as his Israelites, which is a pity, as it is a marvelous piece. Here are the first seven episodes of Part I, from the Introduction to the wonderful soprano aria “Wie bang hat dich mein Lied beweint!” (How anxiously my song mourned for you). The ensemble Rheinische Kantorei is directed by Hermann Max, Martina Lins is the soprano.

Don Carlo Gesualdo, the Czech composer Josef Mysliveček, who lived at approximately the same time as C.P.E. Bach, Samuel Barber and Arthur Honegger were also born this week. We’ll have to write about them another time.Permalink

February 27, 2017. Chopin, Rossini and more. This is one of those overabundant weeks: several composers of great talent, each deserving a separate entry. Frédéric Chopin was born on March 1st of 1810 in a small village of Żelazowa Wola, about 30 miles west of Warsaw, the Polish capital. We celebrate him, probably the greatest piano composer of all time, every year. This time, we’ll play one of his pieces in different interpretations. We’ve done something similar but with just one pianist, when we dedicated an entry to three different interpretations of Chopin’s Polonaise in F-sharp minor, Op. 44 made by Arthur Rubinstein at different stages of his career. Today we’ll play one of the Ballades, No.3 in A-flat Major, which was written in 1841. By then Chopin had been living in Paris for 10 years: he left Poland in 1831 in the aftermath of the November Uprising, a Polish revolt against Russia, which was brutally suppressed by the czarist army. In 1841 Chopin was at the peak of his creative power and still healthy: just one year later the symptoms of the disease that killed him at the age of 39 would start showing up. Ballade no. 3 is in the repertory of every concertizing pianist, so the selection of interpreters is almost infinite. We’ll narrow it down to just three: first, a historical recording made by Sergei Rachmaninov, most likely in the 1930s (here). You’ll notice the freedom of tempos, which would probably be deemed inappropriate today. Even though the recording quality is not very good, the nuanced performance is lovely. The one made by Maurizio Pollini is very different, much tighter and precise, but still warm; the overall lines are wonderful. The performance by Ivan Moravec, made in 1966 (here), is probably the most idiosyncratic and the most lyrical. It’s slower by a minute than Pollini’s. If you go to our library, you’ll also find several recordings made by “our” pianists: Sophia Agranovich, Gianluca Di Donato and Mario Carreño among them.

born on March 1st of 1810 in a small village of Żelazowa Wola, about 30 miles west of Warsaw, the Polish capital. We celebrate him, probably the greatest piano composer of all time, every year. This time, we’ll play one of his pieces in different interpretations. We’ve done something similar but with just one pianist, when we dedicated an entry to three different interpretations of Chopin’s Polonaise in F-sharp minor, Op. 44 made by Arthur Rubinstein at different stages of his career. Today we’ll play one of the Ballades, No.3 in A-flat Major, which was written in 1841. By then Chopin had been living in Paris for 10 years: he left Poland in 1831 in the aftermath of the November Uprising, a Polish revolt against Russia, which was brutally suppressed by the czarist army. In 1841 Chopin was at the peak of his creative power and still healthy: just one year later the symptoms of the disease that killed him at the age of 39 would start showing up. Ballade no. 3 is in the repertory of every concertizing pianist, so the selection of interpreters is almost infinite. We’ll narrow it down to just three: first, a historical recording made by Sergei Rachmaninov, most likely in the 1930s (here). You’ll notice the freedom of tempos, which would probably be deemed inappropriate today. Even though the recording quality is not very good, the nuanced performance is lovely. The one made by Maurizio Pollini is very different, much tighter and precise, but still warm; the overall lines are wonderful. The performance by Ivan Moravec, made in 1966 (here), is probably the most idiosyncratic and the most lyrical. It’s slower by a minute than Pollini’s. If you go to our library, you’ll also find several recordings made by “our” pianists: Sophia Agranovich, Gianluca Di Donato and Mario Carreño among them.

Gioachino Rossini, who stood at the origins of the bel canto opera, was born on February 29th of 1792. A melodic genius, he was known to work incredibly fast. He composed 62 operas, but, even though he lived for 76 years, all of them were written within a period of just 20 years: his last opera, Guillaume Tell (William Tell) was composed in 1829, when Rossini was 37. It’s said that he was late composing the overture for La gazza larda (The thieving magpie), so, to ensure that it was done in time, the producer locked Rossini in a room. As he wrote the pages of the score, he was throwing them out of a window; on the other side copyists were picking them up and creating the orchestral parts for musicians to rehearse at the very last moment. Here is the result, as interpreted by the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra under the direction of Claudio Abbado.

Bedřich Smetana was also born this week, on March 2nd of 1824. A talented composer, he created the Czech national school, very much like the Great Five did in Russia around the same time. He’s probably best known for a set of symphonic poems Má vlast and the opera The Bartered Bride. In 1854 he wrote Piano Trio in G minor, following the death of his older daughter at the age of four of scarlet fever (his second daughter died earlier that same tragic year of tuberculosis). Here it is in the performance by the Lincoln Trio. This year, the violinist Desirée Ruhstrat, the cellist David Cunliffe, and Marta Aznavoorian, piano, were nominated for a Grammy in the Best Chamber Music/Small Ensemble Performance category. Our congratulations to the wonderful ensemble.

Antonio Vivaldi was also born this week (on March 3rd of 1678), we’ll get back to him another time.Permalink

February 20, 2017. Handel. George Frideric Handel, one of the greatest composers of the Baroque, was born in Halle on February 23rd of 1685. We’ve written about him many times (here and here, for example), so on this occasion we’ll look into a period of his life following his departure from Italy. Handel lived there for about seven years, from 1703 to 1710. His operas, (especially Agrippina, which was staged during the Carnival in Venice at the end of 1709) and his oratorios and cantatas were so successful that by the end of his stay, while just 25 years old, he was already world famous. Among his admirers were Prince Ernst Georg of Hanover, and the Duke of Manchester, the English ambassador, both of whom invited Handel to their countries. Handel chose Germany and traveled to Hanover, where he was appointed Kapellmeister. We should remind ourselves of an unusual twist in the British royal lineage: by 1710 the Elector of Hanover, Georg Ludwig, was the acknowledged successor to the English throne and, upon Queen Anne’s death would become King George I of England. His son, Prince elector Georg II August, would become King George II. So, Handel was living at the court with intimate ties to Britain. Handel was given a big salary and a special travel allowance, which he used to travel to London in the autumn of 1710. London was always a musical city; one recent development at the time was the popularity of Italian operas, especially when sung by Italian castratos. Giovanni Bononcini was the acknowledged master of opera – that is till Handel’s arrival. As soon as he got to London, Handel set to work on a new opera; to speed up the process he reused some of the material he had written earlier in Italy. The opera was called Rinaldo, and the title role was sung by Nicolo Grimaldo, a castrato known as Nicolini. Nicolini, who became famous for performing major parts in operas by Alessandro Scarlatti, Porpora, Vinci and Bononcini, became one of Handel’s favorite singers. These days the role of Rinaldo is usually sung by mezzo-sopranos or countertenors; Cecilia Bartoli is one of the best interpreters (here she is in the famous aria Lascia ch'io pianga).

and here, for example), so on this occasion we’ll look into a period of his life following his departure from Italy. Handel lived there for about seven years, from 1703 to 1710. His operas, (especially Agrippina, which was staged during the Carnival in Venice at the end of 1709) and his oratorios and cantatas were so successful that by the end of his stay, while just 25 years old, he was already world famous. Among his admirers were Prince Ernst Georg of Hanover, and the Duke of Manchester, the English ambassador, both of whom invited Handel to their countries. Handel chose Germany and traveled to Hanover, where he was appointed Kapellmeister. We should remind ourselves of an unusual twist in the British royal lineage: by 1710 the Elector of Hanover, Georg Ludwig, was the acknowledged successor to the English throne and, upon Queen Anne’s death would become King George I of England. His son, Prince elector Georg II August, would become King George II. So, Handel was living at the court with intimate ties to Britain. Handel was given a big salary and a special travel allowance, which he used to travel to London in the autumn of 1710. London was always a musical city; one recent development at the time was the popularity of Italian operas, especially when sung by Italian castratos. Giovanni Bononcini was the acknowledged master of opera – that is till Handel’s arrival. As soon as he got to London, Handel set to work on a new opera; to speed up the process he reused some of the material he had written earlier in Italy. The opera was called Rinaldo, and the title role was sung by Nicolo Grimaldo, a castrato known as Nicolini. Nicolini, who became famous for performing major parts in operas by Alessandro Scarlatti, Porpora, Vinci and Bononcini, became one of Handel’s favorite singers. These days the role of Rinaldo is usually sung by mezzo-sopranos or countertenors; Cecilia Bartoli is one of the best interpreters (here she is in the famous aria Lascia ch'io pianga).

Rinaldo was a tremendous success but Handle had to return to Hanover, where he stayed for another year and a half. He obtained a leave from the court and moved to London by the end of 1712. There, he wrote two more operas, and even though they were not as successful as Rinaldo, which had continued to be staged practically every season; his popularity didn’t suffer. In the summer of 1714 the Elector of Hanover moved to London; on August 1st Queen Anne suffered a stroke and died, and George was proclaimed the King. Even though his relationship with Handel during the previous two years had gotten frostier (George resented that Handel preferred London to his court in Hanover) it became more cordial after the coronation. Te Deum and Jubilate, which Handel composed in 1714, were performed for the King, after which George doubled Handel’s salary. During the next five years, Handel didn’t write a single opera, concentrating instead on orchestral compositions and chamber pieces. His most successful composition of the period was Water Music, an orchestral suite written for George I to accompany him on his boat trip up the Thames. Water Music consists of three separate suites; here’s the first one, performed by the Academy Of St. Martin in the Fields under the direction of the late Neville Marriner.Permalink

February 13, 2017. Through the ages and countries. This week affords us an unusually broad view of the development of European music, from the late 16th century to today. Michael Praetorius was born in February 5th of 1571 in Creuzburg, Thuringia (other sources state his birthday as February 15th of that year). At the time, Germany’s musical culture was rather underdeveloped. There was a not a single significant German composer, whereas in Italy the late 16th century was considered late Renaissance: Palestrina and Lasso were born half a century before Praetorius, while Giovanni Gabrieli and Carlo Gesualdo were a generation older. Praetorius had a local musical education, and the only early encounter with a significant foreign composer that we are aware of was with John Dowland, who was invited by Duke Heinrich Julius of Brunswick-Wolfenbütte to meet with his court composer. In this sense Praetorius was a singularly German composer. Extremely prolific (he composed twelve hundred chorales) Praetorius exerted much influence over many composers, starting with the young Heinrich Schütz and through him on a generation of German musicians, including Johann Sebastian Bach. Later in life, when he was living and working in the cosmopolitan Dresden, he became more familiar with and influenced by the contemporary Italians; some of Praetorius’s compositions of the time clearly anticipate the arrival of the Baroque. In 1619, two years before his untimely death, Praetorius published a set of choral works called Polyhymnia Caduceatrix et Panegyrica. Here’s a wonderful chorale from that set, Puer natus in Bethlehem. It’s performed by the Gabrieli Consort.

Praetorius was born in February 5th of 1571 in Creuzburg, Thuringia (other sources state his birthday as February 15th of that year). At the time, Germany’s musical culture was rather underdeveloped. There was a not a single significant German composer, whereas in Italy the late 16th century was considered late Renaissance: Palestrina and Lasso were born half a century before Praetorius, while Giovanni Gabrieli and Carlo Gesualdo were a generation older. Praetorius had a local musical education, and the only early encounter with a significant foreign composer that we are aware of was with John Dowland, who was invited by Duke Heinrich Julius of Brunswick-Wolfenbütte to meet with his court composer. In this sense Praetorius was a singularly German composer. Extremely prolific (he composed twelve hundred chorales) Praetorius exerted much influence over many composers, starting with the young Heinrich Schütz and through him on a generation of German musicians, including Johann Sebastian Bach. Later in life, when he was living and working in the cosmopolitan Dresden, he became more familiar with and influenced by the contemporary Italians; some of Praetorius’s compositions of the time clearly anticipate the arrival of the Baroque. In 1619, two years before his untimely death, Praetorius published a set of choral works called Polyhymnia Caduceatrix et Panegyrica. Here’s a wonderful chorale from that set, Puer natus in Bethlehem. It’s performed by the Gabrieli Consort.

Francesco Cavalli was born February 14th of 1602, just some 30 years after Praetorius, but he belonged to a completely different musical world. Renaissance music, with its polyphony was a thing of the past; Claudio Monteverdi composed L’Orfeo, thus establishing the new musical form - opera. Cavalli, who was born in Lombardy, as a teenager moved to Venice where he was a singer at the St. Mark’s Basilica. Monteverdi was the music director there and became Cavalli’s teacher. Cavalli wrote his first opera in 1639 when he was already a mature composer (most of his early compositions were church music). He went on to write 41 operas, many of which survive to this day. Cavalli was instrumental in developing opera as a musical genre: when his started, opera was in its infancy, and by the time he wrote his last opera in 1673, it was a mature (and extremely popular) art. Here’s the aria Piante ombrose from his early opera, L'Amore Innamorato. Nuria Rial is the soprano. Christina Pluhar leads the ensemble L'Arpeggiata.

Another Italian, Arcangelo Corelli was born fifty years later, on February 17th of 1653. He grew up in the musical environment of flourishing Baroque. At the age of 13 Arcangelo moved to Bologna, one of the music centers of Italy, famous for a major school of violin playing. At the age of seventeen, already a fine violinist, Corelli became a member of the Accademia Filarmonica. He moved to Rome around 1675, where he found patrons in Queen Christina and, later, Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni. He performed, composed and taught: many of his pupils, such as Francesco Geminiani and Pietro Locatelli became famous as composers and violinist. Here’s Corelli’s Concerto Grosso, Op. 6 no.4 performed by I Musici.

We’ll skip Luigi Boccherini, a wonderful Italian composer of the classical era and jump straight into the 20th century. György Kurtág was born on February 19th of 1926. Together with his good friend György Ligeti, Kurtág is one of the most interesting contemporary composers. Here’s his Stele, performed by the Berlin Philharmonic under the direction of Claudio Abbado.Permalink