Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

December 26, 2016. Christmas 2016. Merry Christmas to all our listeners! It's become a tradition to play excerpts from Bach’s Christmas Oratorio around this time. The Oratorio was written for the Christmas season of 1734, when Bach was the Cantor of the Thomasschule and the most important musician in Leipzig. The oratorio wasn’t completely original: it incorporated music from several previously written cantatas. The text was supplied by Picander, a poet, librettist and a frequent Bach collaborator. We've already played the complete Part I, which describes the birth of Jesus, the first movement (Sinfornia) of Part II (here) and the wonderful alto aria Schlafe, mein Liebster, genieße der Ruh (Sleep, my beloved, enjoy Your rest), here. The Second part was written for the second day of Christmas, or December 26th and describes the Annunciation to the Shepherds. On the day of the premier, it was actually performed twice: first, in the early morning of the 26th, in Thomaskirche, and in the afternoon – in the Nikolaikirche. The second part incorporates music from two cantatas, BWV 213 Laßt uns sorgen and BWV 214, Tönet, ihr Pauken! You can listen to the complete Part II of Christmas Oratorio here. It runs for about 27 minutes. John Eliot Gardiner conducts the English Baroque Soloists and the Monteverdi Choir. Bernarda Fink is the alto, Christoph Genz is the tenor.

season of 1734, when Bach was the Cantor of the Thomasschule and the most important musician in Leipzig. The oratorio wasn’t completely original: it incorporated music from several previously written cantatas. The text was supplied by Picander, a poet, librettist and a frequent Bach collaborator. We've already played the complete Part I, which describes the birth of Jesus, the first movement (Sinfornia) of Part II (here) and the wonderful alto aria Schlafe, mein Liebster, genieße der Ruh (Sleep, my beloved, enjoy Your rest), here. The Second part was written for the second day of Christmas, or December 26th and describes the Annunciation to the Shepherds. On the day of the premier, it was actually performed twice: first, in the early morning of the 26th, in Thomaskirche, and in the afternoon – in the Nikolaikirche. The second part incorporates music from two cantatas, BWV 213 Laßt uns sorgen and BWV 214, Tönet, ihr Pauken! You can listen to the complete Part II of Christmas Oratorio here. It runs for about 27 minutes. John Eliot Gardiner conducts the English Baroque Soloists and the Monteverdi Choir. Bernarda Fink is the alto, Christoph Genz is the tenor.

The fresco above, Adoration of the child with St. Jerome, is by Pinturicchio. It’s located in the Della Rovere Chapel of the church of Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome. It was created in or around 1484, 150 years before the Oratorio.Permalink

December 19, 2016. Dunstaple, Des Prez and Victoria. As the end of the year approaches, we’d like to commemorate some of the composers, most of them of the Renaissance era, that fall off our regular calendar, as their birthdates remain unknown to us. It’s especially appropriate as Christmas is approaching and most works of that time were liturgical in nature. John Dunstaple was born around 1390. He served in the court of John of Lancaster, a son of King Henry IV and a brother of Henry V. John led the British forces in many battles of the Hundred Year War with France (he was the one to capture Joan of Arc) and for several years was the Governor of Normandy. It’s likely that Dunstaple stayed with John in Normandy. From there his music spread around the continent, which is quite remarkable considering that a major war was raging in France. Dunstaple’s influence was significant, especially affecting musicians of the Burgundian school; the reason was both musical and political, as Burgundy was allied with England in its war against France. Dunstaple’s La Contenance Angloise, (“English manner”) influenced not only the two greatest composers of Burgundy, Guillaume Dufay and Gilles Binchois but even musicians of the generation that followed, like Ockeghem and Busnoys. Here’s Dunstaple’s motet Quam Pulchra Es, performed by the Hilliard Ensemble.

remain unknown to us. It’s especially appropriate as Christmas is approaching and most works of that time were liturgical in nature. John Dunstaple was born around 1390. He served in the court of John of Lancaster, a son of King Henry IV and a brother of Henry V. John led the British forces in many battles of the Hundred Year War with France (he was the one to capture Joan of Arc) and for several years was the Governor of Normandy. It’s likely that Dunstaple stayed with John in Normandy. From there his music spread around the continent, which is quite remarkable considering that a major war was raging in France. Dunstaple’s influence was significant, especially affecting musicians of the Burgundian school; the reason was both musical and political, as Burgundy was allied with England in its war against France. Dunstaple’s La Contenance Angloise, (“English manner”) influenced not only the two greatest composers of Burgundy, Guillaume Dufay and Gilles Binchois but even musicians of the generation that followed, like Ockeghem and Busnoys. Here’s Dunstaple’s motet Quam Pulchra Es, performed by the Hilliard Ensemble.

Josquin des Prez, one of the greatest Franco-Flemish composers, was born around 1450, probably in the County of Hainaut, which occupied the land on the border between modern-day Belgium and France but back then was part of the Duchy of Burgundy (it was inherited by the dukes at the end of the 14th century). The Duchy was one of the most developed European realms, both economically and artistically. Philip the Good, the duke who ruled from 1419 to 1467, was famous as a patron of painters, Jan van Eyck and Roger van der Weyden among them. Guillaume Dufay, the most renowned composer of his time, worked in duke’s employ. Very little is known about Josquin’s youth. It’s assumed that around 1477 he traveled to Aix-en-Provence and was a singer in the chapel of René, Duke of Anjou. Around 1480 he worked in Milan, probably in the service of Cardinal Ascanio Sforza. And it was probably Sforza who introduced Josquin to the Papal court in Rome. From 1489 to 1495 Josquin sang in the papal choir; a wall of the Sistine Chapel bears a graffito with his name. All the while he was also composing: we know that some of his motets are dated to those years. He probably moved to Milan around 1498 to work for the Sforzas again, and after Milan fell to the French he moved to France. In 1503 he was hired by Ercole, the Duke of Ferrara. It was here that he composed the popular Miserere, a motet for five voices in plainchant, which was probably inspired by the life and execution of Girolamo Savonarola (you can listen to it here, performed by the ensemble De Labyrintho, Walter Testolin conducting). In 1504 Josquin left Ferrara and returned to Condé-sur-l'Escaut, not far from where he was born. He lived there till his death in 1521.

We started at the very beginning of the music of the Renaissance and here is a piece that was written toward the end of it, the exquisite Taedet Animam Meam (My soul is weary of my life) by one of the greatest composers of the High Renessaince, Tomás Luis de Victoria. Victoria was born in 1548 in Spain, near the city of Ávila, spent 20 years in Rome but then returned to Spain. Taedet is one of his last compositions, written in 1605.Permalink

December 12, 2016. Beethoven. This week we celebrate Ludwig van Beethoven’s 236th birthday. He was baptized on December 17th of 1770, so it’s often assumed that he was born the day before, on December 16th. We alternate the celebration by either focusing on the piano sonatas written during a certain period, or on his symphonies. Last year it was symphonies nos. 3 and 4, and today we’ll present the next one, probably his most celebrated, symphony no. 5. It was written between 1804 and 1808 and premiered in Vienna on December 22nd of 1808 with Beethoven conducting (it’s worth reading about the amazing concert at which the Symphony was presented: events like that do not happen often, if ever). The Fifth is one of the most recorded compositions in history so to select one is impossible. We wanted to go for a Furtwangler recording, but their audio quality isn’t great. Everybody knows the Karajans (there are several and practically all are wonderful), so we decided on a superb recording made in 1975 by the late Carlos Kleiber with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra. Enjoy it here. ♫

day before, on December 16th. We alternate the celebration by either focusing on the piano sonatas written during a certain period, or on his symphonies. Last year it was symphonies nos. 3 and 4, and today we’ll present the next one, probably his most celebrated, symphony no. 5. It was written between 1804 and 1808 and premiered in Vienna on December 22nd of 1808 with Beethoven conducting (it’s worth reading about the amazing concert at which the Symphony was presented: events like that do not happen often, if ever). The Fifth is one of the most recorded compositions in history so to select one is impossible. We wanted to go for a Furtwangler recording, but their audio quality isn’t great. Everybody knows the Karajans (there are several and practically all are wonderful), so we decided on a superb recording made in 1975 by the late Carlos Kleiber with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra. Enjoy it here. ♫

Symphony no. 5. As familiar and beloved as the Eroica, Seventh, or Choral Symphonies may be, none approach the immortal status of Beethoven’s own Symphony No. 5. Not only is it the one work most associated with its composer’s name, it is the work most synonymous with the word “symphony” itself. The hammer blows of its opening notes, so well-known even outside of classical music, are instantly recognizable. Even to merely distinguish the symphony by its key – “the C minor” – conjures the same association as saying “Beethoven’s Fifth.”

Beethoven began work on what would become the Fifth Symphony in 1805, shortly after completing the Eroica. As was mentioned in the discussion of the Symphony No. 4, a possible combination of artistic judgment – that so stern a composition as the projected C minor Symphony should not follow one as equally grand and serious – and his engagement to the Countess Theresa Brunswick prompted Beethoven to temporarily set aside the C minor and compose instead the ebullient Symphony in B-flat major. The C minor Symphony was then taken back up in 1807 and completed in 1808. Thus, the composition of the work spans much of Beethoven’s doomed engagement to the Countess – its first sketches predating the engagement, and its completion occurring during the troublesome period in which the lovers were separated, which led eventually to Beethoven himself breaking off the engagement in 1810. The completion of the C minor Symphony also coincided with the composition of its successor, the Pastoral. Both works were jointly dedicated to Prince Lobkowitz and Count Rasumovsky, premiered together in 1808, and published the following year.

The premiere took place on December 22, 1808 in Vienna during a colossal program directed by the composer himself that included the Pastoral Symphony, selections from the Mass in C, the Fourth Piano Concerto, and the Choral Fantasy. Curiously, on that program, the Pastoral Symphony was performed first and given as No. 5, while the C minor was performed during the concert’s latter half and designated as No. 6. The numbers were not reversed until the publication of the score and parts the following year. Despite a program filled with such remarkable compositions, the premiere of the Fifth Symphony was rather lackluster. The sheer length of the concert exhausted the audience, and the orchestra was ill-prepared for the Herculean task. However, it was not long before the Symphony met with success. E. T. A. Hoffman penned an enthusiastic and lavish review of the work in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung. It premiered in England in 1816, in Paris in 1828, and was performed in the inaugural concert of the New York Philharmonic in 1842. By then, it was a staple of the orchestra repertoire, even outpacing Beethoven’s other symphonies in number of performances. (Continue reading here).

Permalink

December 5, 2016. Berlioz, Les Troyens. Several wonderful composers were born this week: Francesco Geminiani, on this day in 1687 in Lucca, a somewhat minor but still interesting Baroque composer and violinist; Henryk Górecki, on December 6th of 1933 – a leading Polish modernist (and, surprisingly, commercially successful) composer; Bernardo Pasquini, December 7th of 1637 in Tuscany, an important opera and keyboard composer of the Alessandro Scarlatti and Antonio Corelli generation. And then, also on December 7th but of 1863, another Italian – Pietro Mascagni of the Cavalleria Rusticana fame. The following day, December 8th, is the birthday of the Finnish national composer, Jean Sibelius; he was born in 1865. Also on the same day but in 1890, a leading Czech composer of the early 20th century was born – Bohuslav Martinu, who used a neoclassical idiom and, sometimes, jazz, as in his whimsical La Revue de Cuisine. Also on the same day was born a wonderful Soviet composer Mieczysław (Moisey) Weinberg. Weinberg was born in Warsaw, fled to the Soviet Union at the outbreak of WWII (his family stayed behind and perished during the Holocaust), and eventually became “the third great Soviet composer,” after Shostakovich and Prokofiev, except that he remained practically unknown to the public: his work was banned during the Stalin time, in 1953 he was arrested during the anti-Jewish campaign and survived only because Stalin died several months later. Even though Weinberg was “rehabilitated” by the Soviets, performances of his music were rare. During the last 10 years, his opera The Passenger gained prominence after being staged in several major theaters, including the Lyric Opera. Also this week (and what a week!), two more birthdays on the 10th of December: César Franck, born in 1822, and one of the greatest composers of the 20th century, Olivier Messiaen, in 1908.

modernist (and, surprisingly, commercially successful) composer; Bernardo Pasquini, December 7th of 1637 in Tuscany, an important opera and keyboard composer of the Alessandro Scarlatti and Antonio Corelli generation. And then, also on December 7th but of 1863, another Italian – Pietro Mascagni of the Cavalleria Rusticana fame. The following day, December 8th, is the birthday of the Finnish national composer, Jean Sibelius; he was born in 1865. Also on the same day but in 1890, a leading Czech composer of the early 20th century was born – Bohuslav Martinu, who used a neoclassical idiom and, sometimes, jazz, as in his whimsical La Revue de Cuisine. Also on the same day was born a wonderful Soviet composer Mieczysław (Moisey) Weinberg. Weinberg was born in Warsaw, fled to the Soviet Union at the outbreak of WWII (his family stayed behind and perished during the Holocaust), and eventually became “the third great Soviet composer,” after Shostakovich and Prokofiev, except that he remained practically unknown to the public: his work was banned during the Stalin time, in 1953 he was arrested during the anti-Jewish campaign and survived only because Stalin died several months later. Even though Weinberg was “rehabilitated” by the Soviets, performances of his music were rare. During the last 10 years, his opera The Passenger gained prominence after being staged in several major theaters, including the Lyric Opera. Also this week (and what a week!), two more birthdays on the 10th of December: César Franck, born in 1822, and one of the greatest composers of the 20th century, Olivier Messiaen, in 1908.

But the composer we really wanted to talk about, notwithstanding the immense talent we just listed above, is Hector Berlioz, born on December 11th of 1803. And the reason is not that he’s one of the greatest composers of all time (which of course he is) but that the Lyric Opera of Chicago is currently staging his monumental opera, Les Troyens. It is long, about 3 hours and 40 minutes of music (plus intermissions that push the performance closer to 5 hours altogether), it is intense – no recitatives, no frilly entr'actes, just continuous orchestral and vocal music. And despite it consisting of two separate parts and five acts, the libretto is surprisingly coherent, unlike some of Wagner’s undertakings. Berlioz wrote the libretto himself, after Virgil’s poem Aeneid. The first part, called The Taking of Troy, which starts in Troy after the apparent departure of the Greeks, describes Cassandra’s futile attempts to warn the Trojans of the looming dangers. The Trojans, relieved that the war is over, do not believe her till it’s too late: the infamous giant horse, which the Greeks left as a “gift,” is full of soldiers. They pillage and murder; Trojan women commit suicide rather than falling into slavery, while the ghost of Hector convinces Aeneas, who’s ready to fight to the end, to leave the fallen city and build a new Troy, which of course is Rome. The second part takes place in Carthage, ruled by Queen Dido. Aeneas and his cohorts, after being lost at sea, find refuge there. The chaste queen, who still mourns her husband, eventually falls in love with Aeneas, and though they lead an idyllic life, it’s clear that Aeneas must leave, as he has a mission – to build the new Troy. The ghost of Hector, this time accompanied by the dead Cassandra and King Priam, remind him of that mission, and, reluctantly, Aeneas gathers his men and sets sail for Italy. Dido is furious that Aeneas abandoned her. She burns all the gifts she received from Aeneas, prophesizes that a general from Carthage will take revenge on Rome (as Hannibal did, to an extent), and then stabs herself to death.

In the Chicago production Susanne Graham was superb as Dido. Here she is in the Morte de Didonne scene. This 2003 Paris recording features Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, John Eliot Gardiner conducting. And here is the famous Chasse royale et orage (The Royal hunt and the storm) purely orchestral ballet scene, performed by the Royal Opera House orchestra, Sir Colin Davis conducting.

PermalinkNovember 28, 2016. Lully, Part I. Jean-Baptiste Lully was born on this day in 1632 in Florence, Tuscany. His family was of modest means and not musical. Giovanni Battista, as he was called in those days, probably studied music with local friars. Then his life changed overnight. How it happened that Roger de Lorraine, the chevalier de Guise, picked a 14-year old boy to become a tutor in Italian for his niece, we don’t know. What we do know is that the niece was none other than Anne-Marie-Louise d’Orléans, known as the “Grande Mademoiselle,” the eldest daughter of Gaston, the Duke of Orléans, a brother of Louis XIII and, therefore, the niece of King Louis XIV. The Grande Mademoiselle, then 19, was living in the Palais des Tuileries, and it was in the palace that Jean-Baptiste completed his musical education. One wonders whether Lully had any knowledge of Italian music before he was brought to France; it seems likely that he became familiar with it later on, when he was already employed by the court. In addition to music, Jean-Baptiste was taught to dance, and, apparently was very good at that – at least that was the capacity in which he started at the Royal court. The Second Fronde (the Fronde of the Nobles) compromised the position of the Grande Mademoiselle, and in 1653 she was forced to leave Paris. Soon after, Jean-Baptiste returned to the city and was brought to the court as a dancer in a Ballet royal de la nuit, a sumptuous production which called for a large number of performers. (The 14-year old King, who loved to dance, performed as Apollo – it was his debut). The performance went well and Lully was accepted to the corp. As Lully was already dabbling in composition, he was appointed a “composer of instrumental music,” but his duties were to combine dancing and composing, with an emphasis on dancing. Jean-Baptiste was so good at it that he got noticed by the King. Soon he became the King’s favorite – first as a dancer and, later, as a composer. Back then, the traditions of French court music were rather unusual, at least by our standards. For example, several composers were supposed to create a single ballet. The ballets were complex affairs, not just with dances but also with different vocal parts and instrumental interludes. Some composers were considered to be especially good in writing vocal music, while others were famous as instrumentalists (the young Lully was known for his dance music). For example, Ballet de la Nuit, mentioned above, was written by at least three people. It wasn’t till 1656 that Lully would have a chance to create a complete ballet of his own, L'Amour malade; that happened partly because of the influence of the Italian musicians in the entourage of the King’s chief advisor, Cardinal Mazarin, himself an Italian. L'Amour malade, a vast production with mimes, dancers (Lully being one of them) and singers, was a huge success. From that point on, he was considered the greatest ballet composer in France. That would become his main preoccupation for the next several years: he would write ballets for the court and even add ballet scenes to operas of other composers. A rather scandalous story happened when the famous Italian opera composer, Francesco Cavalli, came to town with his fine opera, Ercole amante. Lully decided to add several ballet pieces to it. The entire production became a six-hour affair; the king, the queen and the court danced to the ballet music, which received all the praise, while the rest of the opera was panned. Cavalli left Paris soon after.

music with local friars. Then his life changed overnight. How it happened that Roger de Lorraine, the chevalier de Guise, picked a 14-year old boy to become a tutor in Italian for his niece, we don’t know. What we do know is that the niece was none other than Anne-Marie-Louise d’Orléans, known as the “Grande Mademoiselle,” the eldest daughter of Gaston, the Duke of Orléans, a brother of Louis XIII and, therefore, the niece of King Louis XIV. The Grande Mademoiselle, then 19, was living in the Palais des Tuileries, and it was in the palace that Jean-Baptiste completed his musical education. One wonders whether Lully had any knowledge of Italian music before he was brought to France; it seems likely that he became familiar with it later on, when he was already employed by the court. In addition to music, Jean-Baptiste was taught to dance, and, apparently was very good at that – at least that was the capacity in which he started at the Royal court. The Second Fronde (the Fronde of the Nobles) compromised the position of the Grande Mademoiselle, and in 1653 she was forced to leave Paris. Soon after, Jean-Baptiste returned to the city and was brought to the court as a dancer in a Ballet royal de la nuit, a sumptuous production which called for a large number of performers. (The 14-year old King, who loved to dance, performed as Apollo – it was his debut). The performance went well and Lully was accepted to the corp. As Lully was already dabbling in composition, he was appointed a “composer of instrumental music,” but his duties were to combine dancing and composing, with an emphasis on dancing. Jean-Baptiste was so good at it that he got noticed by the King. Soon he became the King’s favorite – first as a dancer and, later, as a composer. Back then, the traditions of French court music were rather unusual, at least by our standards. For example, several composers were supposed to create a single ballet. The ballets were complex affairs, not just with dances but also with different vocal parts and instrumental interludes. Some composers were considered to be especially good in writing vocal music, while others were famous as instrumentalists (the young Lully was known for his dance music). For example, Ballet de la Nuit, mentioned above, was written by at least three people. It wasn’t till 1656 that Lully would have a chance to create a complete ballet of his own, L'Amour malade; that happened partly because of the influence of the Italian musicians in the entourage of the King’s chief advisor, Cardinal Mazarin, himself an Italian. L'Amour malade, a vast production with mimes, dancers (Lully being one of them) and singers, was a huge success. From that point on, he was considered the greatest ballet composer in France. That would become his main preoccupation for the next several years: he would write ballets for the court and even add ballet scenes to operas of other composers. A rather scandalous story happened when the famous Italian opera composer, Francesco Cavalli, came to town with his fine opera, Ercole amante. Lully decided to add several ballet pieces to it. The entire production became a six-hour affair; the king, the queen and the court danced to the ballet music, which received all the praise, while the rest of the opera was panned. Cavalli left Paris soon after.

Here are several excerpts from an early ballet by Lully called Ballet des Plaisirs. It was composed in 1655; Lully danced several roles in the production. Aradia Baroque Ensemble, a Canadian group, is conducted by Kevin Mallon.Permalink

November 21, 2016. Eight composers in seven days. This is one of the weeks when practically every day allows us to celebrate a talented, if not necessarily great, composer. Monday is Francisco Tarrega’s birthday: he was born on November 21st of 1852 in Villareal, Spain. A virtuoso guitarist and an imaginative, if rather conservative, composer, he was part of the romantic revival of Spanish music at the second half of the 19th century. A friend of Isaac Albéniz and Enrique Granados, he lived most of his life in Barcelona. Here’s one of his most famous compositions, Capricho Árabe, performed by Eric Henderson. And speaking of guitar compositions, some of the most famous were written by another Spanish composer whose birthday falls on Tuesday: Joaquin Rodrigo, the author of Concierto de Aranjuez and Concierto Andaluz was born on November 22nd of 1901. Rodrigo went blind at the age of three after contracting diphtheria. This didn’t stop him from composing (he wrote in Braille music code which was then transcribed into regular music notation), studying and travelling. He went to Paris to study with Paul Dukas and it was in Paris that he composed his most famous piece, Concierto de Aranjuez for the guitar and orchestra. It’s interesting that while Tarrega was a virtuoso guitar player, Rodrigo never learned to play the instrument. Here’s another well-known piece by Rodrigo written for the guitar and orchestra: his Fantasía para un gentilhombre (Fantasia for a Gentleman). Fantasia was written at the request of Andrés Segovia who premiered it in 1958. Segovia is the soloist in this recording, and the conductor, Enrique Jordá, was conducting the premier. The orchestra, though, is different: in the recording it’s “Symphony Of The Air”, while the premier was played by the San Francisco Symphony.

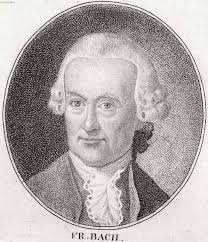

Also on Tuesday we mark the birthday of Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, Johan Sebastian’s oldest son. Friedmann was born on November 22nd of 1710 in Weimar, where his father worked in the employ of Wilhelm Ernst, duke of Saxe-Weimar. A talented composer, he never found satisfying employment throughout his entire life. As a young man, he worked as the organist at Sophienkirche in Dresden, then moved to Halle, taking the appointment at Liebfrauenkirch. While his early years in Halle seemed to be agreeable, eventually Friedemann grew unsatisfied with his position, and so were his superiors. He left Halle without securing employment anywhere else and spent the rest of his life in difficult circumstances. Eventually he was forced to sell his music library, which also contained the sheet music he inherited from his father. Friedemann died on July 1st of 1784 in Berlin, still remembered as a supreme organist and a major composer but leaving his family in poverty. Here’s a lovely Duet for two violas, performed by Ryo Terakado and François Fernandez of the Ricercar Consort.

Friedmann was born on November 22nd of 1710 in Weimar, where his father worked in the employ of Wilhelm Ernst, duke of Saxe-Weimar. A talented composer, he never found satisfying employment throughout his entire life. As a young man, he worked as the organist at Sophienkirche in Dresden, then moved to Halle, taking the appointment at Liebfrauenkirch. While his early years in Halle seemed to be agreeable, eventually Friedemann grew unsatisfied with his position, and so were his superiors. He left Halle without securing employment anywhere else and spent the rest of his life in difficult circumstances. Eventually he was forced to sell his music library, which also contained the sheet music he inherited from his father. Friedemann died on July 1st of 1784 in Berlin, still remembered as a supreme organist and a major composer but leaving his family in poverty. Here’s a lovely Duet for two violas, performed by Ryo Terakado and François Fernandez of the Ricercar Consort.

Also born on the same day, November 22nd, was one of the most important composers of the 20th century, Benjamin Britten. And speaking of important 20th century composers: three more were born this week. Krzysztof Penderecki on November 23rd of 1933, Alfred Schnittke on November 24th of 1934, and Virgil Thomson on November 25th of 1897. And to round things out, we should mention Sergei Taneyev, a prolific composer, a wonderful pianist and a good friend of Tchaikovsky’s (he successfully premiered Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto in Moscow after it flopped in St-Petersburg where Gustav Kross was the soloist). Taneyev was born on November 25th of 1856.Permalink