Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

July 13, 2015. Chopin’s Nocturnes, part I. With a paucity of memorable anniversaries this week, we’ll turn again to one of our incidental longer articles, this time on Chopin’s Nocturnes. Chopin wrote 21 of them; we’ll discuss ten here, and the rest in the follow-up article. As always, when we can, we illustrate the music with performances by the young artists in our library. Nocturne op. 9, no. 1 is performed by the young Russian pianist Anastasya Terenkova; no. 2 from the same opus – by the Mexican pianist Mariusz Carreño; and no. 3 – by Jingjing Wang (China). The Nocturne op. 15, no. 3 is played by the Serbian-American pianist Ivan Ilić. Nocturnes op. 27 are performed by the British pianist of Nigerian descent Sodi Braide (no. 1) and the Chinese pianist Ang Li (no. 2). Opus 32, no. 2 is played by the South-Korean pianist Angela Youngmi Choi. We had to “borrow” three performances: Maurizio Pollini plays the nocturne op. 15, no. 1, while Arthur Rubinstein performs the second piece from that opus. The nocturne op. 32, no. 1 is by Vladimir Ashkenazy. The 1835 watercolor portrait above is by Maria Wodzińska, who became engaged to Chopin in 1836. The engagement was dissolved a year later on the insistence of Maria’s father because of Chopin’s poor health. ♫

Nocturnes. Chopin wrote 21 of them; we’ll discuss ten here, and the rest in the follow-up article. As always, when we can, we illustrate the music with performances by the young artists in our library. Nocturne op. 9, no. 1 is performed by the young Russian pianist Anastasya Terenkova; no. 2 from the same opus – by the Mexican pianist Mariusz Carreño; and no. 3 – by Jingjing Wang (China). The Nocturne op. 15, no. 3 is played by the Serbian-American pianist Ivan Ilić. Nocturnes op. 27 are performed by the British pianist of Nigerian descent Sodi Braide (no. 1) and the Chinese pianist Ang Li (no. 2). Opus 32, no. 2 is played by the South-Korean pianist Angela Youngmi Choi. We had to “borrow” three performances: Maurizio Pollini plays the nocturne op. 15, no. 1, while Arthur Rubinstein performs the second piece from that opus. The nocturne op. 32, no. 1 is by Vladimir Ashkenazy. The 1835 watercolor portrait above is by Maria Wodzińska, who became engaged to Chopin in 1836. The engagement was dissolved a year later on the insistence of Maria’s father because of Chopin’s poor health. ♫

The French word “nocturne,” and its Italian equivalent “notturno,” mean “pertaining to the night.” The term itself is quite old. Since the Middle Ages it has pertained to divisions in the canonical hours of Matins. As the name of a type of musical composition, it is also older than popularly thought. It was first applied in the 18th century to compositions of a lighter character and in several movements to be performed at night, much in the same manner as the serenade. Examples of this type of piece include works by Haydn and the Serenata Notturno, K.239 by Mozart. The nocturne as a miniature for piano, however, did not appear until the early part of the following century when the Irish composer, John Field, first used the term in this sense and pioneered an entirely new genre of compositions. Field’s nocturnes featured an expressive, song-like melody over an accompaniment of broken chords. Their construction and expression was simple, and it would take a more profound genius to reveal the full potential of Field’s creation.

As a young man, Chopin greatly admired John Field, and was strongly influenced by the Irishman’s piano and composition techniques. Others perceived Field’s influence on Chopin. Friedrich Kalkbrenner even once inquired if Chopin was a pupil of Field. Indeed, the affinity between the two was enough that Field even began to be described as “Chopin-esque” (much to his chagrin as he once described Chopin as a “sickroom talent”).

Following in Field’s footsteps, Chopin wrote his first pair of nocturnes while still in Poland, though they were not published until well after his death. His first published essays in the genre were composed in the early years of the 1830s, surrounding his departure from his native Poland, brief stay in Vienna and ultimate voyage to Paris. As one might expect, these early essays owned much to Field, though already offered glimpses of Chopin’s burgeoning genius. During his lifetime, Chopin published eighteen nocturnes, the last appearing in 1846. Three more appeared after his death: the early E minor Nocturne, alluded to above, in 1855 as op. posth. 72, and two other works in 1870 that were not assigned opus numbers.

Like his waltzes and mazurkas, Chopin’s treatment of the nocturne progressed far beyond the conventional expectations of the form. With the dances, Chopin transformed them into compelling concert miniatures; with the nocturne, he raised it to a level of artistry far beyond the Fieldian prototype and wrung from it emotions of peaceful serenity and poignant melancholy. Chopin maintained the defining elements of the genre established by Field: a vocal-like melody, often finely ornamented, allotted to the right hand, an accompaniment of broken chords in the left, and frequent use of the pedal. To this model Chopin added the influences of Italian and French operatic arias, a freedom and complexity of rhythm taken from Classical models, and a keen use of counterpoint. (Continue reading here).

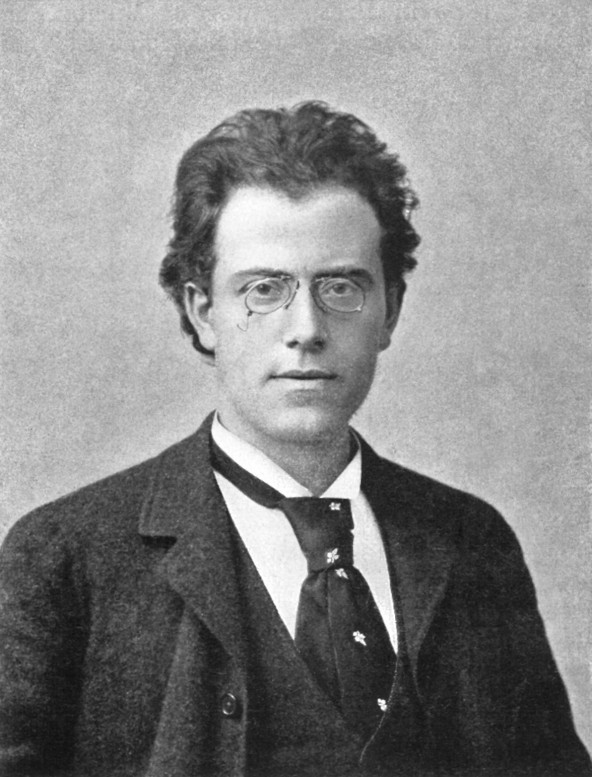

PermalinkJuly 6, 2015. Gustav Mahler. A friend traveling around Central Europe writes from Melk, famous for its castle: “We’re sitting in a café on the main square, surrounded by the locals. The sun is shining, a wind band is playing, everybody seems to be enjoying themselves. It could be the early 1900s, or 1939, right after the Anschluss – things don’t change much in Austria.” He then adds, “Mauthausen is right over the hills, but would anybody care?” He’s going to visit Maiernigg next. Even though Mahler’s name hasn’t been mentioned, this short description is full of allusion to the composer’s life: his childhood fascination with military bands, his birth in one of the provinces of a great empire, his habit of composing in a remote cabin by a lake, and, also, for good measure, Austrian historical anti-Semitism. Gustav Mahler was born on July 7th of 1860 in a small town of Kaliště (then Kalischt), near Jihlava (Iglau) in Bohemia, at that time a part of Austria-Hungary, into an assimilated Jewish family. We followed his life around the time he composed his First (here) and Second (here) symphonies. By 1893, the year Mahler started working on his Third Symphony, he had assumed the position of the Chief conductor at Hamburg State theater, having left the more prestigious Royal Hungarian Opera. Mahler would’ve stayed in Budapest longer (he mounted several very successful opera productions, and his Don Giovanni was hailed by Brahms himself) but an ongoing conflict with management made his departure inevitable (anti-Semitism also played a role). In Hamburg his relationship with the director Bernhard Pohl (or Pollini, as he preferred to be known) was much more amicable. During his maiden season Mahler conducted several highly acclaimed productions of Wagner operas: Siegfried, Tannhäuser and Tristan (somewhat surprisingly, he also staged Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin). At that time he established a pattern, which he would follow for the rest of his life: conducting during the season and composing in the summer. He built himself a small one-room cabin in Steinbach, on lake Attersee in the Salzkammergut. There he composed the Second and Third symphonies (the cabin was just for composing – Mahler lived in an inn in the village). In 1894 the young Bruno Walter joined Mahler at the State Theater and soon became a friend and an acolyte. The Third Symphony was completed in 1896. By then Mahler was tired of Hamburg and ready to move on. He started a campaign for a position at the Vienna Hofoper, the main opera theater in all of the empire. In the Vienna of the day a Jew couldn’t be appointed to a significant post at the imperial theater; Mahler, never a practicing Jew, removed that barrier by converting to Roman Catholicism. That happened in February of 1897. Two months later he was appointed a Kapellmeister, and in September of that year – the music director of the opera.

It could be the early 1900s, or 1939, right after the Anschluss – things don’t change much in Austria.” He then adds, “Mauthausen is right over the hills, but would anybody care?” He’s going to visit Maiernigg next. Even though Mahler’s name hasn’t been mentioned, this short description is full of allusion to the composer’s life: his childhood fascination with military bands, his birth in one of the provinces of a great empire, his habit of composing in a remote cabin by a lake, and, also, for good measure, Austrian historical anti-Semitism. Gustav Mahler was born on July 7th of 1860 in a small town of Kaliště (then Kalischt), near Jihlava (Iglau) in Bohemia, at that time a part of Austria-Hungary, into an assimilated Jewish family. We followed his life around the time he composed his First (here) and Second (here) symphonies. By 1893, the year Mahler started working on his Third Symphony, he had assumed the position of the Chief conductor at Hamburg State theater, having left the more prestigious Royal Hungarian Opera. Mahler would’ve stayed in Budapest longer (he mounted several very successful opera productions, and his Don Giovanni was hailed by Brahms himself) but an ongoing conflict with management made his departure inevitable (anti-Semitism also played a role). In Hamburg his relationship with the director Bernhard Pohl (or Pollini, as he preferred to be known) was much more amicable. During his maiden season Mahler conducted several highly acclaimed productions of Wagner operas: Siegfried, Tannhäuser and Tristan (somewhat surprisingly, he also staged Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin). At that time he established a pattern, which he would follow for the rest of his life: conducting during the season and composing in the summer. He built himself a small one-room cabin in Steinbach, on lake Attersee in the Salzkammergut. There he composed the Second and Third symphonies (the cabin was just for composing – Mahler lived in an inn in the village). In 1894 the young Bruno Walter joined Mahler at the State Theater and soon became a friend and an acolyte. The Third Symphony was completed in 1896. By then Mahler was tired of Hamburg and ready to move on. He started a campaign for a position at the Vienna Hofoper, the main opera theater in all of the empire. In the Vienna of the day a Jew couldn’t be appointed to a significant post at the imperial theater; Mahler, never a practicing Jew, removed that barrier by converting to Roman Catholicism. That happened in February of 1897. Two months later he was appointed a Kapellmeister, and in September of that year – the music director of the opera.

The Third Symphony consists of six movements, which, according to Mahler himself, comprise two uneven parts: the first part consists of the long first movement, and the second one – of the remaining five. The 1st movement (here) runs for more than 30 minutes, practically a symphony in itself. (Depending on the performance, the complete symphony usually runs between one hour and 30 minutes to an hour and 40 minutes). Mahler gave it an informal title "Pan Awakes, Summer Marches In." This is where we can hear the military-band music that so affected the young composer. Some of it is almost unbearably vulgar (Mahler marked certain passages as “Grob!” – “coarse” or “gross” in German) and some is heavenly, in association with Pan. The 2nd movement, "What the Flowers in the Meadow Tell Me," as Mahler called it (here), is a short (about nine minutes) lyrical intermezzo in Tempo di Menuetto. The 3rd movement, an about 16 minute-long Scherzando (here), Mahler called "What the Animals in the Forest Tell Me." The 4th movement, Misterioso (or "What Man Tells Me," hear) introduces a contralto singing from Nietzsche's “Midnight Song” from Also sprach Zarathustra. The Children’s choir joins in the 5th movement Cheerful in tempo, or, as Mahler called it "What the Angels Tell Me", is based on one of the songs from Mahler’s Des Knaben Wunderhorn (here). The majestic 6th movement (here) is one of the greatest symphonic pieces ever written. Langsam – Ruhevoll – Empfunden (Slowly, tranquil, deeply felt), Mahler subtitled it "What Love Tells Me." The late Claudio Abbado is inspiring as he leads the Lucerne Festival Orchestra. Anna Larsson is the contralto.

PermalinkJune 29, 2015. The Tchaikovsky competition and several birthdays. The XV Tchaikovsky competition is in full swing. This year it was split between two cities, Moscow and St.-Petersburg (the pianists and violinists perform in Moscow, the cellists and singers – in St-Pete). Medici.tv does a great job broadcasting live performances; we highly recommend it. For the pianists, this year is probably more challenging than ever: instead of the regular three rounds, the competition consists of five, if you include the preliminary hearings. The second round is split in two: the performance of a large composition plus a piece by a Russian composer, followed by a Mozart concerto accompanied by a chamber orchestra. Asiya Korepanova, who played Rachmaninov’s Piano Sonata no. 1 so well at the Hess memorial concert last year, was not as successful during the first round (nerves, one has to assume) and didn’t make it to the 2nd round. Lucas Debargue, a 24 year-old Frenchman, is the public’s favorite. His 2nd round Gaspard de la Nuit was extremely good. Another Lukas (this one with a “k,” though), with the last name of Geniušas, a Lithuanian born in Moscow who also happens to be the grandson of Vera Gornostayeva, is also playing very well. (Gornostayeva, the famous Russian pianist and pedagogue, died less than half a year ago, on January 19th of this year). A Russian-German Maria Mazo played Hammerklavier in the 2nd round and did a great job of it, but her Mozart concerto (no. 21) was rather subdued. Still, we thought that she deserves to make it into the 3rd round, but the jury thought otherwise. The violinists are also through to the 3rd round. We have recordings of one of them, Clara-Jumi Kang. Like the pianists, the violinists also had to play a Mozart concerto in the second part of the second round. Clara played the concerto no. 5, and wonderfully so. We’ll write some more about the Tchaikovsky competition soon.

singers – in St-Pete). Medici.tv does a great job broadcasting live performances; we highly recommend it. For the pianists, this year is probably more challenging than ever: instead of the regular three rounds, the competition consists of five, if you include the preliminary hearings. The second round is split in two: the performance of a large composition plus a piece by a Russian composer, followed by a Mozart concerto accompanied by a chamber orchestra. Asiya Korepanova, who played Rachmaninov’s Piano Sonata no. 1 so well at the Hess memorial concert last year, was not as successful during the first round (nerves, one has to assume) and didn’t make it to the 2nd round. Lucas Debargue, a 24 year-old Frenchman, is the public’s favorite. His 2nd round Gaspard de la Nuit was extremely good. Another Lukas (this one with a “k,” though), with the last name of Geniušas, a Lithuanian born in Moscow who also happens to be the grandson of Vera Gornostayeva, is also playing very well. (Gornostayeva, the famous Russian pianist and pedagogue, died less than half a year ago, on January 19th of this year). A Russian-German Maria Mazo played Hammerklavier in the 2nd round and did a great job of it, but her Mozart concerto (no. 21) was rather subdued. Still, we thought that she deserves to make it into the 3rd round, but the jury thought otherwise. The violinists are also through to the 3rd round. We have recordings of one of them, Clara-Jumi Kang. Like the pianists, the violinists also had to play a Mozart concerto in the second part of the second round. Clara played the concerto no. 5, and wonderfully so. We’ll write some more about the Tchaikovsky competition soon.

Christoph Willibald Gluck, a great German opera composer, was born on July 2nd of 1714 in Erasbach, Bavaria. Last year we celebrated his 300th anniversary and played several arias and overtures from Orfeo ed Euridice and Iphigénie en Aulide. Two more of Gluck’s operas are still very popular: Alceste and Iphigénie en Tauride.Alceste was written in 1776, soon after Orfeo. Calzabigi, the librettist, wrote a preface to Alceste, a manifest of sorts, which Gluck signed. In the preface they spelled out some of the principles that Gluck pushed to make opera more natural: no da capo arias, no virtuoso improvisations, fewer recitatives, flowing melodic lines. You can hear it all in "Divinités du Styx,” an aria from Act 1. Jessye Norman is Alceste, The Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra is conducted by Serge Baudo.

The Czech composer Leoš Janáček was born on July 3rd, 1854 in a small village in Moravia, then part of the Austria-Hungary. As a boy he studied the piano and the organ, but eventually became interested in composing. In 1879 he enrolled in the Leipzig conservatory and later moved to Vienna to study composition there. Like the Hungarian composers Béla Bartók and Zoltan Kodály a generation later, Janáček was interested in folk music and used peasant tunes in his symphonic and piano pieces. His early compositions were mostly for the piano: he started a piano cycle, On an Overgrown Path, in 1901; it became one of his most popular compositions (you can listen to it in the performance by Ieva Jokubaviciute). Eventually, he turned to operas – that’s what he’s most famous for these days. His first one, Jenufa, was written in 1904 and acquired the status of the “Moravian national opera.” Two more operas followed, Katia Kabanova and The Cunning Little Vixen; they rightly are considered among the most interesting operas of the 20th century. Janáček also wrote a number of significant orchestral pieces and chamber music. Here is his Quartet no. 2 subtitled “Intimate Letters,” performed by Pacifica Quartet.

Two things are interesting about Louis-Claude Daquin, a French composer and virtuoso keyboard player, who was born on July 4th of 1694. One is that he was of Jewish descent: there were very few Jewish composers during that time. And he probably would not have become one had his Italian ancestors not converted to Catholicism. The event took place in the city of Aquino, thus the original name, D’Aquino, (which was later frenchified to Daquin). Of his considerable output, one piece is famous, The Cuckoo, from a suite for the harpsichord. Here it is, performed by the wonderful British harpsichordist George Malcolm.Permalink

June 22, 2015. Schumann’s Dichterliebe, Part II. In the absence of any significant birthdays this week we decided to publish the second part of the article on Robert Schumann’s song cycle Dichterliebe (A Poet's Love). The first part was published here. As a reminder, Dichterliebe, o n texts by Heinrich Heine from his Lyrisches Intermezzo, was written in 1840. That was the year Schumann married Clara Wieck; it also turned into his Liederjahr – the year of songs: he wrote almost 140 of them in a tremendous creative spurt. Dichterliebe is probably the best known. To illustrate the cycle, we used recordings made by Fritz Wunderlich. All but the one were made in Salzburg in 1965. The recording of Die alten, bösen Lieder was made during a concert in Usher Hall, Edinburgh, on August 4th of 1966. Wunderlich tragically died just one month later; he was 35 years old. ♫

n texts by Heinrich Heine from his Lyrisches Intermezzo, was written in 1840. That was the year Schumann married Clara Wieck; it also turned into his Liederjahr – the year of songs: he wrote almost 140 of them in a tremendous creative spurt. Dichterliebe is probably the best known. To illustrate the cycle, we used recordings made by Fritz Wunderlich. All but the one were made in Salzburg in 1965. The recording of Die alten, bösen Lieder was made during a concert in Usher Hall, Edinburgh, on August 4th of 1966. Wunderlich tragically died just one month later; he was 35 years old. ♫

The poet’s state becomes even more pitiful in “Das ist ein Flöten und Geigen” (“There is fluting and fiddling,” here) as he witnesses the joyous festivities of the marriage of his beloved to another man. He gazes upon the merriment, watching her dance (“Da tanzt wohl den Hochzeitreigen / Die Herzallerliebste mein”) to the sound of flutes, fiddles, shawms, and drums. Betwixt the sounds of the instruments, the angels weep for the lonely poet (“Dazwischen schluchzen und stöhnen / Die guten Engelein”). Schumann’s setting portrays the dance of the beloved and her wedding guests. However, its D minor tonality and chromatic harmonies undoubtedly identify that the listener is viewing the scene through the prism of the poet’s broken heart.

Utter despair sets in the following song, “Hör’ ich das Liedchen klingen” (“I hear the dear song sounding,” here). Pained by watching his beloved married to another, the poet now hears the sweet song she once sang, a symbol that her love is forever no longer his. In his desolation, he seeks the solace of nature, wandering deep into the forest to weep. Schumann’s setting is through-composed in the key of G minor. The doleful vocal melody closes first in the key of the subdominant at the conclusion of the first stanza, poignantly affected by a Neapolitan sixth. The second stanza then slowly descends back to the tonic of G minor. Against the vocal melody is an accompaniment of descending arpeggios, which with the song’s slow tempo depict the falling tears of the poet. As with many of Schumann’s song, the climax comes as the vocalist exits. Shadowing the final notes of the melody, the piano begins a heartrending coda which culminates as chromatically ascending harmonies beneath a tonic pedal suddenly break into a descending passage of sixteenth notes through almost three octaves. Here, the listener beholds the poet’s heart bursting with pain (“So will mir die Brust zerspringen / Vor wildem Schmerzendrang”). (Continue reading here)Permalink

June 15, 2015. Stravinsky and more. Several composers were born this week: Edvard Grieg, Norway’s national composer (he was born on June 15th of 1843), the Frenchman Charles Gounod (born on June 17th of 1818), Jacques Offenbach, who was born just a year later, on June 20th of 1819 in Cologne to a Jewish cantor but lived most of his life in Paris and received a Légion d’Honneur from the hands of the Emperor Napoleon III; and Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach, the ninth of Johann Sebastian Bach’s children (he was born on June 21st of 1732). To mark these birthdays, we’ll play: Solveig’s song, from Grieg’s original incidental music to Peer Gynt with the Russian soprano Anna Netrebko (here); Gounod’s lovely Serenade, exquisitely performed by Joan Sutherland (with her husband, Richard Bonynge, on the piano, here); a comic aria Les oiseaux dans la charmille from Offenbach’s only opera, The Tales of Hoffmann with another Australian soprano, Emma Matthews (here); and the only non-vocal entry, Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach’s Piano Concerto E Major, with Cyprien Katsaris and Orchestre de Chambre du Festival d`Echternach (here).

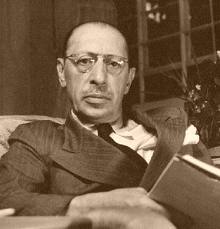

But the most significant composer of them all was, without a doubt, the great Igor Stravinsky. Stravinksy was born on June 17, 1882 in Oranienbaum, outside of Saint Petersburg. During his long life Stravinsky moved from one country to another (after leaving Russia he lived in France, Switzerland and the US); he also didn’t stay still compositionally, often discarding one style, however successful it was for him, and adopting a new musical paradigm. It is hard to imagine that the same composer who wrote The Rite of Spring, with its wild colors and brutal rhythms, would just 15 years later create a ballet as abstract and serene as Apollon musagète, or, for that matter, some years later, another ballet, Agnon, written in the twelve-tone system. Probably the only other person who could reinvent himself as often and with the same immense success was Pablo Picasso. Stravinsky naturally possessed a tremendous technique, which allowed him to imitate or directly quote other composers while maintaining the artistic integrity and originality of the composition. He used this skill with uncanny virtuosity when he wrote the ballet Le Baiser de la Fée (The Fairy's Kiss), an homage to his favorite composer, Tchaikovsky. The ballet was commissioned in 1927 by the famous Russian dancer Ida Rubinstein; Stravinsky completed the ballet in 1928, on the 35th anniversary of Tchaikovsky’s death (it was premiered in November of that year). The libretto was based on Hans Christian Andersen's story The Ice Maiden. Bronislava Nijinska (Vaclav’s sister) was the choreographer. Stravinsky used several of Tchaikovsky’s piano pieces and songs, and recognizably Tchaikovskian sonorities throughout the ballet. A tremendously inventive piece, it marked another step in the development of Stravinsky’s compositional style. In 1934 he wrote a suite based on the music of the ballet; this suite, which Stravinsky called Divertimento, is usually performed in concerts. We’ll hear it in the performance by the Bulgarian National Radio Symphony Orchestra, Mark Kadin conducting.

But the most significant composer of them all was, without a doubt, the great Igor Stravinsky. Stravinksy was born on June 17, 1882 in Oranienbaum, outside of Saint Petersburg. During his long life Stravinsky moved from one country to another (after leaving Russia he lived in France, Switzerland and the US); he also didn’t stay still compositionally, often discarding one style, however successful it was for him, and adopting a new musical paradigm. It is hard to imagine that the same composer who wrote The Rite of Spring, with its wild colors and brutal rhythms, would just 15 years later create a ballet as abstract and serene as Apollon musagète, or, for that matter, some years later, another ballet, Agnon, written in the twelve-tone system. Probably the only other person who could reinvent himself as often and with the same immense success was Pablo Picasso. Stravinsky naturally possessed a tremendous technique, which allowed him to imitate or directly quote other composers while maintaining the artistic integrity and originality of the composition. He used this skill with uncanny virtuosity when he wrote the ballet Le Baiser de la Fée (The Fairy's Kiss), an homage to his favorite composer, Tchaikovsky. The ballet was commissioned in 1927 by the famous Russian dancer Ida Rubinstein; Stravinsky completed the ballet in 1928, on the 35th anniversary of Tchaikovsky’s death (it was premiered in November of that year). The libretto was based on Hans Christian Andersen's story The Ice Maiden. Bronislava Nijinska (Vaclav’s sister) was the choreographer. Stravinsky used several of Tchaikovsky’s piano pieces and songs, and recognizably Tchaikovskian sonorities throughout the ballet. A tremendously inventive piece, it marked another step in the development of Stravinsky’s compositional style. In 1934 he wrote a suite based on the music of the ballet; this suite, which Stravinsky called Divertimento, is usually performed in concerts. We’ll hear it in the performance by the Bulgarian National Radio Symphony Orchestra, Mark Kadin conducting.

PermalinkJune 8, 2015. Schumann’s Dichterliebe. The great German composer Robert Schumann was born on this day in 1810. We write about him every year (for example, here and here in the past couple of years), so this time we’ll do something different: publish an article on the first eight songs of Dichterliebe. Schumann wrote more than 300 songs, but A Poet’s Love cycle contains some of his greatest. There are so many wonderful recordings of Dichterliebe that it was difficult to decide which one to use to illustrate the cycle. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau alone made four different recordings, two of them with remarkable pianists: Alfred Brendel in 1985 and, live, with Vladimir Horowitz, in 1976. Gérard Souzay, a wonderful French baritone, also recorded it several times, once with Afred Cortot (and there’s another recording with Cortot, in which he accompanies Charles Panzéra). Hermann Prey made a tremendous recording, and so did the great German soprano Lotte Lehmann. Out of all of these and many more, we decided on Fritz Wunderlich – the beauty of his crystalline voice, his perfect diction, the natural, unpretentious manner devoid of any affectations make his interpretation, in our opinion, extraordinary. The recording was made live on August 19th of 1965 during the Salzburg Festival. Hubert Giesen was at the piano. ♫

years), so this time we’ll do something different: publish an article on the first eight songs of Dichterliebe. Schumann wrote more than 300 songs, but A Poet’s Love cycle contains some of his greatest. There are so many wonderful recordings of Dichterliebe that it was difficult to decide which one to use to illustrate the cycle. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau alone made four different recordings, two of them with remarkable pianists: Alfred Brendel in 1985 and, live, with Vladimir Horowitz, in 1976. Gérard Souzay, a wonderful French baritone, also recorded it several times, once with Afred Cortot (and there’s another recording with Cortot, in which he accompanies Charles Panzéra). Hermann Prey made a tremendous recording, and so did the great German soprano Lotte Lehmann. Out of all of these and many more, we decided on Fritz Wunderlich – the beauty of his crystalline voice, his perfect diction, the natural, unpretentious manner devoid of any affectations make his interpretation, in our opinion, extraordinary. The recording was made live on August 19th of 1965 during the Salzburg Festival. Hubert Giesen was at the piano. ♫

Schumann’s composed almost exclusively for his own instrument, the piano, during his early years as a composer. The 1830s saw the creation of some of his most well-known compositions, including Papillons, Kinderszenen, and the Fantasie in C. However, in 1840, with virtually no warning, Schumann composed no less than 138 songs. This remarkable creative outpouring has since become known as his “Liederjahr,” or “Year of Song.” Yet, this sudden change, nor the abundance of music written, was purely coincidental. Instead, it makes the culmination of his courtship of Clara Wieck, and their long-awaited and hard-won marriage.

Schumann and Clara first met in March 1828 at a musical evening in the home of Dr. Ernst Carus. Schumann was so impressed with Clara’s skill at the piano that he soon after began piano lessons with her father, Friedrich. During this time he lived in the Wieck’s household, and he and Clara quickly formed a close friendship. With time, their friendship blossomed into a romantic, although clandestine, relationship. On Clara’s 18th birthday, Schumann proposed to her, and she accepted. Friedrich, on the other hand, had less than a favorable opinion of Schumann, and refused to grant permission for Schumann to marry his daughter. This placed a great strain on their relationship, yet they remained devoted to each other by exchanging love letters and meeting in secret. For a moment’s glance of Clara as she left one of her concerts, Schumann would wait for hours in a café. The couple eventually sued Friedrich, and after a lengthy court battle, Clara was finally allowed to marry Schumann without her father’s consent. The wedding took place in 1840. (Continue reading here).Permalink