Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

November 9, 2015. Couperin and more. François Couperin, Alexander Borodin, Paul Hindemith and Aaron Copland were all born this week: Couperin on November 10th of 1668; Borodin on November 12th of 1833; Hindemith on November 16th of 1995; and five years later, on November 14th of 1900 – Copland. It’s a profoundly diverse group and very little links them together, except that all of them are part of the classical music canon. Even Hindemith and Copland, who belonged to the same generation, couldn’t be farther apart. We’ve written about all of them before (you may search our unwieldy archive to find the older entries), so this time we’ll simply celebrate the diversity and juxtapose several characteristic pieces.

The earliest genuinely original work by Paul Hindemith was a series of pieces he called Kammermusik. The first one was written in 1922, the last (eighth) – in 1928. Here’s Kammermusik No. 1, for 12 instruments, Op. 24 no. 1. Bold, very energetic, it’s scored for an unusual combination of flute, clarinet, bassoon, trumpet, harmonium, piano, string quintet and percussion. Members of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra are conducted by Riccardo Chailly.

Alexander Borodin, a chemist and an occasional composer of unusual talent, is famous for his opera Prince Igor. Borodin also wrote a small number of chamber pieces and some piano music. Here’s his Petite Suite. It was published in 1885 but written in a course of several previous years. The Suite is performed by Tatyana Nikolayeva. Nikolayeva was a good friend of Dmitry Shostakovich and made a famous recording of his 24 Preludes and Fugues. Renowned in the Soviet Union, she was not very well known in the West. She started traveling abroad after the Perestroika, but on November 13th of 1993 suffered a stroke during a concert in San Francisco; she was playing Shostakovich’s 24 Preludes and Fugues. Nikolayeva couldn’t finish the performance and died nine days later.

Aaron Copland, one of the most important and influential American composers of the 20th century, may be closer to Borodin than any other composer in our group. Borodin, even though a strong proponent of “absolute music,” was a Russian national composer through and through. His melodies, though they rarely quote folk tunes, are recognizably “Russian.” And so is Copland: his music is quintessentially American, often “populist” and deceptively simple. A Brooklyn Jew of Lithuanian origin, he used folk tunes and old Shaker songs (he also borrowed from jazz and Mexican music). We have a large selection of Copland’s music in our library, so please search or browse and you’ll find some wonderful pieces.Permalink

November 2, 2015. Handel’s Water Music and Music for the Royal Fireworks. We’re publishing an essay by Joseph DuBose about what is probably the most popular orchestral music in all of George Frideric Handel’s output. We illustrate it with the 1972 recordings made by Neville Marriner with his Academy of St Martin in the Fields. ♫

George Frideric Handel’s output. We illustrate it with the 1972 recordings made by Neville Marriner with his Academy of St Martin in the Fields. ♫

On July 17, 1717, King George I conducted a lavish affair upon the Thames River. As one rumor goes, it was an effort to outdo his own son, Prince George II, who was enjoying the limelight of British social circles. At eight o’clock that night, the King and his entourage boarded a royal barge at Whitehall Place and sailed up the Thames to Chelsea. An accompanying barge, provided by the City of London, held some fifty instrumentalists who performed music by Handel for the King’s entertainment. A great number of Londoners came out to witness the incredible spectacle—so many, in fact, that the Daily Courant newspaper reported there was “so great a Number of Boats, that the whole River in a manner was cover'd.”

Another rumor surrounding the event suggests that Handel’s music for the event was composed as a means to regain the King’s good graces. Before inheriting the British throne, George, as the Elector of Hanover, had employed Handel as Kapellmeister beginning in 1710. Yet, two years later, Handel decided to relocate to England where he received a yearly salary from Queen Anne. Handel’s abrupt departure from Germany purportedly caused some animosity between him and his employer. Once George ascended the British throne, Handel found himself suddenly in the position of needing to regain the King's favor. Supposedly, Handel was apprehensive in approaching King George, but saw the King's party as the perfect opportunity. On the other hand, an equally plausible explanation is both men knew that George would soon be King of Great Britain, and that he gave Handel his permission to venture on ahead of him to London. Regardless, the king was so impressed with the music that he ordered it repeated three times by the time he returned to Whitehall from Chelsea, suggesting that the musicians played continuously from 8 p.m. until well after midnight (with the exception of a break while King George I went ashore at Chelsea).

Though Handel’s music for the event was such a great success, there exists no reliable documentation that the music known today as Water Music was, in fact, the exact music performed on that occasion. While it is known that several of the numbers were quite popular in London, none of the music was initially published. Three movements—two minuets and the overture—appeared in 1720 and 1725, respectively. John Walsh published an eleven movement edition in 1733, and later followed up with an expanded nineteen movement arrangement for harpsichord. The first complete edition did not appear until 1788 and was published after extensive research by Samuel Arnold. This edition has become the authoritative Water Music, and was the basis for Friedrich Chrysander’s Gesellschaft edition published in 1886. Yet, despite an authoritative edition, some doubt remains even today around the exact ordering of the movements. Generally, however, Handel’s Water Music is arranged into three separate suites, HWV 348-50, based on the character and instrumentation of the movements. The first suite, by the far longest, contains nine movements in the keys of F major and D minor, and features horns with an orchestra of oboes, bassoon, and strings. The middle suite, in D major, adds trumpets; while the third, in G major, is more delicately scored with flutes. (Continue reading here)Permalink

October 26, 2015. Scarlatti and Paganini. Domenico Scarlatti, a son of the famous opera composer Alessandro Scarlatti, was born on this day in 1685, the same year as Johann Sebastian Bach and George Frideric Handel. Domenico, the sixth of ten children of Alessandro, was born in Naples: a year earlier his father became Maestro di Cappella to the Spanish viceroy of Naples. He probably studied music with his father; later – with Bernardo Pasquini, a noted opera composer and harpsichordist. Alessandro knew Pasquini well: together with Arcangelo Corelli they were members of the famous Accademia degli Arcadi in Rome, a literary academy and, at that time, a leading cultural institution. In 1705 Alessandro wrote a long letter to Ferdinando de’ Medici, the Grand Duke of Florence, touting Domenico’s talents. They were acknowledged but no position was offered. Instead Alessandro sent his son to Venice were he stayed for several years. In 1708 Domenico traveled to Rome on the invitation of Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni. There he was persuaded to enter into a keyboard competition with Handel. They were judged to be equal at the clavichord but Handel was acknowledged a superior organist. The competition didn’t prevent them from becoming good friends. Scarlatti admired Handel’s talents; it’s also said that he crossed himself any time Handel’s name was mentioned: Scarlatti, like many of his contemporaries, thought that Handel was so exceptionally good not without the involvement of black magic. This was also a widespread opinion about Paganini, our other birthday composer, who, according to legend, sold his soul to the devil.

Naples. He probably studied music with his father; later – with Bernardo Pasquini, a noted opera composer and harpsichordist. Alessandro knew Pasquini well: together with Arcangelo Corelli they were members of the famous Accademia degli Arcadi in Rome, a literary academy and, at that time, a leading cultural institution. In 1705 Alessandro wrote a long letter to Ferdinando de’ Medici, the Grand Duke of Florence, touting Domenico’s talents. They were acknowledged but no position was offered. Instead Alessandro sent his son to Venice were he stayed for several years. In 1708 Domenico traveled to Rome on the invitation of Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni. There he was persuaded to enter into a keyboard competition with Handel. They were judged to be equal at the clavichord but Handel was acknowledged a superior organist. The competition didn’t prevent them from becoming good friends. Scarlatti admired Handel’s talents; it’s also said that he crossed himself any time Handel’s name was mentioned: Scarlatti, like many of his contemporaries, thought that Handel was so exceptionally good not without the involvement of black magic. This was also a widespread opinion about Paganini, our other birthday composer, who, according to legend, sold his soul to the devil.

In Rome Domenico found a patron – Maria Casimira, the exiled former Queen of Poland; she made Domenico her maestro di cappella. Domenico was following in his father’s steps: Alessandro occupied a similar position at the court of the exiled Queen Christina of Sweden. Domenico lived in Rome till around 1720. After that he took a trip to Lisbon, and soon after settled in Spain, where he spent the rest of his life. Most of Scarlatti’s Italian musical output was concentrated on operas (Domenico created 13 of them), oratorios and cantatas. He wrote most of his keyboard sonatas – compositions that he’s famous for today – while in Spain. So here’s an example of his operatic work, a rarity: a duet "Se l'alma non t'adora" from, as far as we know, Domenico Scarlatti’s first opera L'Ottavia ristituita al trono. It was premiered in 1703 when Domenico was 18. The singers, both Italian, are Patrizia Ciofi, a coloratura soprano, and Anna Bonitatibus, a mezzo with a flourishing international career. The ensemble Il Complesso Barocco is conducted by Alan Curtis. Curtis, a harpsichordist, musicologist and conductor, died on July 15th of this year.

Another Italian, Niccolò Paganini, was born on October 27th of 1782. In the history of music Paganini is more famous as a performer rather than a composer. His best known work was also his first, a set of 24 “caprices” for violin solo. Here’s Salvatore Accardo playing Caprice no. 2 in B minor, a 1978 recording. And here’s the same caprice, recorded in 1972 by Itzhak Perlman. We don’t know if Paganini really had a deal with the devil but this piece is certainly devilishly difficult.Permalink

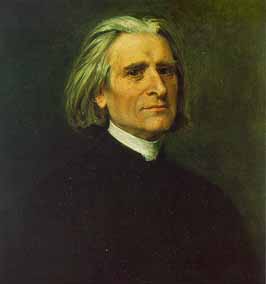

October 19, 2015. Liszt, Ives and Berio. Three very different composers were born this week: two “modernists,” Charles Ives and Luciano Berio, and one great Romantic, Franz Liszt. Liszt, born on October 22nd, 1811, was a tremendous virtuoso. While he was still concertizing (he quit at the age of 35 at the height of his career) he was much more famous as a pianist than a composer. Liszt wrote a number of extremely difficult piano pieces. In his time, he was one of the very few, if not the only one, capable of pulling them off. During the last 20 years or so we’ve been witnessing a revolution in pianism. These days the technique of many young musicians is on a level that was only achieved by very few just a generation ago. Of course technique alone is not enough – one needs to have keen musicianship to become a complete artist, but extraordinary technique can create excitement that’s lacking in more subdued performances. Liszt’s piano pieces are perfectly suited for such feats. Khatia Buniatishvili is one of the young pianists who can dazzle – or infuriate, as the case may be. Some compare her with the young Martha Argerich, and, though they are quite different musically, the drive, energy and the superb technique lend credence to the comparison. Here’s Khatia playing, live, Liszt’s Mephisto Waltz no 1. The recording was made in 2011 at the Verbier Festival. One can find faults in this performance, both technical and musical, but the visceral pleasure is all there.

the height of his career) he was much more famous as a pianist than a composer. Liszt wrote a number of extremely difficult piano pieces. In his time, he was one of the very few, if not the only one, capable of pulling them off. During the last 20 years or so we’ve been witnessing a revolution in pianism. These days the technique of many young musicians is on a level that was only achieved by very few just a generation ago. Of course technique alone is not enough – one needs to have keen musicianship to become a complete artist, but extraordinary technique can create excitement that’s lacking in more subdued performances. Liszt’s piano pieces are perfectly suited for such feats. Khatia Buniatishvili is one of the young pianists who can dazzle – or infuriate, as the case may be. Some compare her with the young Martha Argerich, and, though they are quite different musically, the drive, energy and the superb technique lend credence to the comparison. Here’s Khatia playing, live, Liszt’s Mephisto Waltz no 1. The recording was made in 2011 at the Verbier Festival. One can find faults in this performance, both technical and musical, but the visceral pleasure is all there.

Charles Ives was born on October 20th of 1874. He’s now considered to be very important to the development of American music, the first truly international composer of major talent. During his lifetime, though, he was almost completely ignored. Practically all his adult life Ives worked in the insurance business and was very successful at that; he’s considered the pioneer of estate planning, on which he wrote a treatise. Composing was done in his spare time. His most productive period was from the early 1900s to about 1920 (he didn’t compose much in the second half of his life. He died in 1954). Ives started composing the Concord piano sonata around 1911 and worked on it till 1915. It’s a remarkable piece of music, especially considering the time of the composition. The sonata consists of four movement, each titled after American writers: "Emerson," "Hawthorne,” "The Alcotts" (after Bronson Alcott and Louisa May Alcott), and "Thoreau.” As many of Ives’s piece, it’s long, running about 45 minutes; even 100 years later it’s challenging but very much worth listening to. Here’s the second movement, "Hawthorne,” in the performance by Alexei Lyubimov, a wonderful Russian pianist and a student of Heinrich Neuhaus.

Luciano Berio, one of the most interesting composers of the second half of the 20th century, was born on October 24th of 1925. We wrote about him in some detail last year. To celebrate Berio’s 90th birthday, here’s Sequenza IXa for clarinet, one of the pieces in a set of 14 for solo instruments. It’s performed by Joaquin Valdepeñas.Permalink

October 12, 2015. Johann Sebastian Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos, part II. Today we’ll complete the article on Bach’s great Brandenburg Concertos, covering numbers 3 through 6. You may read the introduction here. As before, we illustrate the concertos with live performances by the Orchestra Mozart of Bologna, Claudio Abbado conducting.

Concerto No. 3 in G major

Believed to be one of the earliest of the Brandenburg Concertos to be written, the Third in G major (here) is scored solely for stings--three each of violins, violas, and cellos--and continuo. Yet, Bach masterfully overcomes the homogenous sound of his chosen ensemble by constantly varying the juxtaposition of the parts. Throughout the entirety of the work no instrument is rarely singled out as a soloist, and it thus sometimes described as "symphonic." Instead, the instruments engage in delightful conversation amongst themselves, whether in sections (as in much of the finale), or more individually, resulting in masterful contrapuntal imitations. Indeed, within the first movement, the ensemble even provides its own ritornello with a unison passage that marks key structural divisions.

masterfully overcomes the homogenous sound of his chosen ensemble by constantly varying the juxtaposition of the parts. Throughout the entirety of the work no instrument is rarely singled out as a soloist, and it thus sometimes described as "symphonic." Instead, the instruments engage in delightful conversation amongst themselves, whether in sections (as in much of the finale), or more individually, resulting in masterful contrapuntal imitations. Indeed, within the first movement, the ensemble even provides its own ritornello with a unison passage that marks key structural divisions.

However, despite its rich and warm sonorities and inviting melodies, the work has long vexed scholars and performers alike. Standing betwixt its two radiant G major movements is a curious, solitary measure in Adagio tempo and consisting of nothing more than a Phrygian half cadence in E minor. Such a cadence frequently concluded a penultimate movement in Baroque times, preparing the way for an ensuing major key finale. And, one might even suspect that a slow movement is perhaps missing from the Concerto if the measure in question did not occur in the middle of a page. Furthermore, scholars have noted that some of Bach's contemporaries, including Corelli, inserted bare cadences in their scores as well. Since this lone measure is hardly an adequate respite, it is quite possible the cadence was meant to frame or conclude a cadenza improvised by one of the performers. Indeed, it is likely the cadence was a form of shorthand that performers of the period would have easily understood, though the certainty of such is perhaps lost, like much of Baroque performance practices were as the 18th century came to close.

With the lack of any certainty in what Bach's expectations were, actual performance practice of the enigmatic Adagio varies. Some, adhering to a strict interpretation, perform the measure as is with no further ornamentation. Others provide varying degrees of embellishment, from simple ornamentations of the two chords by the harpsichord or violin, to lengthy extemporized fantasias that recall themes from the first movement in a manner akin to cadenzas of Classical and Romantic concerti. On the other hand, some go even further and attempt to restore the balance of the standard three-movement concerto form by inserting a slow movement from one of Bach's (usually lesser known) other works. Given the importance of improvisation during the Baroque era, from ornamentation to figured bass realization and even extemporized full-fledged fugues, it is likely that embellishment of the cadence or an improvised cadenza are perhaps the closest solution to Bach's original intentions (continue).Permalink

October 5, 2015. Heinrich Schütz. Giuseppe Verdi and Camille Saint-Saëns were born this week: Verdi on October 9th of 1813, and Saint-Saëns on the same day but in 1835. We’ve written about both of them a number of times. There’s another composer whose anniversary is also celebrated this week, and though he’s very important in the history of music, we’ve never had a chance to write about him. The composer’s name is Heinrich Schutz, and he’s one of the most important German Renaissance predecessors of Johann Sebastian Bach. Schütz was born 100 years before Bach, on October 8th of 1585 in Bad Köstritz, Thuringia. When Heinrich was five, his family moved to Weißenfels, where his father inherited an inn and became a burgomaster. Heinrich demonstrated musical talent from a very early age. In 1598, Maurice, the landgrave of Hesse-Kasse, a tiny principality then part of the Holy Roman Empire, stayed overnight in the family inn and heard Heinrich sing. Maurice, who was himself a musician and composer, was so impressed that he invited Heinrich to his court to study music and further his education (while at the court, Heinrich learned several languages, including Latin, Greek and French). Heinrich sung as a choir boy till his voice broke and then went to study law at Marburg. In 1609 he went to Venice to study music with Giovanni Gabrieli. Even though Gabrieli was 28 years older than Schütz, they became close (Gabrieli left him one of his rings when he died). The master died in 1612 and Schütz returned to Kassel. In 1614 the Elector of Saxony asked Schütz to come to Dresden. The famous Michael Praetorius was nominally in charge of music-making at the court but he had other responsibilities, so the elector was interested in Schütz’s service. Schütz moved to Dresden permanently in 1615. In 1619 he received the title of Hofkapellmeister. Soon after he published his first major work, Psalmen Davids (Psalms of David), a collection of 26 settings of psalms influenced, as one can hear, by Gabrieli. Here’s Psalm 128, “Wohl dem, der den Herren fürchte.” Cantus Cölln and Concerto Palatino are conducted by Konrad Junghänel.

important in the history of music, we’ve never had a chance to write about him. The composer’s name is Heinrich Schutz, and he’s one of the most important German Renaissance predecessors of Johann Sebastian Bach. Schütz was born 100 years before Bach, on October 8th of 1585 in Bad Köstritz, Thuringia. When Heinrich was five, his family moved to Weißenfels, where his father inherited an inn and became a burgomaster. Heinrich demonstrated musical talent from a very early age. In 1598, Maurice, the landgrave of Hesse-Kasse, a tiny principality then part of the Holy Roman Empire, stayed overnight in the family inn and heard Heinrich sing. Maurice, who was himself a musician and composer, was so impressed that he invited Heinrich to his court to study music and further his education (while at the court, Heinrich learned several languages, including Latin, Greek and French). Heinrich sung as a choir boy till his voice broke and then went to study law at Marburg. In 1609 he went to Venice to study music with Giovanni Gabrieli. Even though Gabrieli was 28 years older than Schütz, they became close (Gabrieli left him one of his rings when he died). The master died in 1612 and Schütz returned to Kassel. In 1614 the Elector of Saxony asked Schütz to come to Dresden. The famous Michael Praetorius was nominally in charge of music-making at the court but he had other responsibilities, so the elector was interested in Schütz’s service. Schütz moved to Dresden permanently in 1615. In 1619 he received the title of Hofkapellmeister. Soon after he published his first major work, Psalmen Davids (Psalms of David), a collection of 26 settings of psalms influenced, as one can hear, by Gabrieli. Here’s Psalm 128, “Wohl dem, der den Herren fürchte.” Cantus Cölln and Concerto Palatino are conducted by Konrad Junghänel.

Schütz lived in Dresden for the rest of his life, making periodic extended trips: in 1628 he went to Venice where he met Claudio Monteverdi who became a big influence. He also made several trips to Copenhagen, composing for the royal court. Schütz lived a long life: he died on November 6th of 1672 at the age of 87. Schütz composed mostly sacred choral music, although in 1627 he wrote what is considered the first German opera, Dafne. Unfortunately, even though the libretto survived, the score was lost many years ago. In 1636 Schütz wrote music for the funeral service of Count Henry II of Reuss-Gera called Musikalische Exequien. Here’s the last section, Canticum. English Baroque Soloists and Monteverdi Choir are conducted by John Eliot Gardiner.Permalink