Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

This Week in Classical Music: October 8, 2023. Verdi, War. Today is the 210th anniversary of Giuseppe Verdi’s birth, but we’re not in the mood to celebrate it: it seems inappropriate with the war raging in Israel and Gaza after the Hamas barbaric terrorist attack. There are many trite sayings about the power of music to heal, to make peace, but they all seem shallow in comparison to the news of civilians being killed in cold blood or the horror of the Israeli kids being abducted by Hamas into Gaza. If anything, throughout history music has been used to make war, from military bands leading troops into battle to Nazis using it in concentration camps. (And no, the Ride of the Valkyries wasn’t used in Vietnam by the US helicopter pilots, it was Francis Ford Coppola’s brilliant invention).

war raging in Israel and Gaza after the Hamas barbaric terrorist attack. There are many trite sayings about the power of music to heal, to make peace, but they all seem shallow in comparison to the news of civilians being killed in cold blood or the horror of the Israeli kids being abducted by Hamas into Gaza. If anything, throughout history music has been used to make war, from military bands leading troops into battle to Nazis using it in concentration camps. (And no, the Ride of the Valkyries wasn’t used in Vietnam by the US helicopter pilots, it was Francis Ford Coppola’s brilliant invention).

We thought of maybe using parts of Verdi’s Requiem or the famous chorus of the Hebrew Slaves, Va', pensiero (Fly, my thoughts), from his opera Nabucco, but that didn’t feel right either. So we’ll leave it at that.

Two great pianists were also born this week, Evgeny Kissin, who’ll turn 52 tomorrow, and Gary Graffman, who will celebrate his 95th birthday on the 14th of October. Both are Jewish; Kissin was born in Russia (then the Soviet Union), Graffman’s parents came from Russia. Hamas, if they could, would like to kill all Jews, no matter where they live. And they would definitely not spare musicians.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: October 2, 2023. Giulio Caccini. During the last couple of months, we’ve published several entries on two subjects: one, the musical transition from the Renaissance to the Baroque and early opera, and another, about some unsavory but talented characters in music. The protagonist of today’s entry falls into both categories. Giulio Caccini was born in Rome on October 8th, 1551. One episode that puts him into the “unsavory” category happened in 1576 when Caccini was in Florence employed by the court of Grand Duke Francesco I de’ Medici. Francesco had a brother, Pietro, who was married to the beautiful Eleonora (Leonora) di Garzia di Toledo. Pietro was known to be gloomy and violent, the marriage was unhappy, and Leonora had several affairs. Caccini, attempting to curry favors from the Duke’s family, spied on Leonora and then denounced her and her lover, Bernardino Antinori, to Pietro. Pietro brought Leonora to Villa Medici at Cafaggiolo, where he strangled her with a dog leash. Leonora was 23. Bernardino Antinori was imprisoned and also killed. The whole story is even more sordid and involves other characters and victims, but though fascinating, it goes even further into Italian history and away from music. One note: if the name of Antinori sounds familiar to wine lovers, it’s not by chance – Bernardino’s family has been making wines since 1385. These days Antinori produce some of the best Chiantis and Super-Tuscans in Italy.

Renaissance to the Baroque and early opera, and another, about some unsavory but talented characters in music. The protagonist of today’s entry falls into both categories. Giulio Caccini was born in Rome on October 8th, 1551. One episode that puts him into the “unsavory” category happened in 1576 when Caccini was in Florence employed by the court of Grand Duke Francesco I de’ Medici. Francesco had a brother, Pietro, who was married to the beautiful Eleonora (Leonora) di Garzia di Toledo. Pietro was known to be gloomy and violent, the marriage was unhappy, and Leonora had several affairs. Caccini, attempting to curry favors from the Duke’s family, spied on Leonora and then denounced her and her lover, Bernardino Antinori, to Pietro. Pietro brought Leonora to Villa Medici at Cafaggiolo, where he strangled her with a dog leash. Leonora was 23. Bernardino Antinori was imprisoned and also killed. The whole story is even more sordid and involves other characters and victims, but though fascinating, it goes even further into Italian history and away from music. One note: if the name of Antinori sounds familiar to wine lovers, it’s not by chance – Bernardino’s family has been making wines since 1385. These days Antinori produce some of the best Chiantis and Super-Tuscans in Italy.

Other episodes are not as gruesome but still attest to Caccini’s character. Two more talented composers worked at the court at the same time, Emilio de' Cavalieri and Jacopo Peri. In 1600, the wedding of Henry IV of France and Maria de' Medici was a very important event. Cavalieri, who oversaw all major festivities of the house of Medici, was expected to direct this one as well. The conniving Caccini had him denied the position, and while Cavalieri did write some of the music, it was Caccini who managed the staging (we described this event here). The disappointed Cavalieri left Florence never to return. As for Peri, the stories are more comical. Upon learning that Peri was writing an opera, Euridice, for the wedding of Maria de' Medici to Henry IV, he rushed to compose his own version using the same libretto and had it published before the first performance of Peri’s work. That wasn’t all; Caccini’s daughter Francesca, a talented singer, was to participate in the performance of Peri’s Euridice. Even though Peri wrote the music for the whole opera, Caccini rewrote the parts performed by Francesca and several other singers under his command, all that just to spite Peri and promote himself. Francesca Caccini, by the way, turned into an excellent composer in her own right. Her opera, La liberazione di Ruggiero dall’isola d’Alcina (The Liberation of Ruggiero from the Island of Alcina) was just staged by the Chicago Haymarket Opera Company (yesterday was the last performance).

composers worked at the court at the same time, Emilio de' Cavalieri and Jacopo Peri. In 1600, the wedding of Henry IV of France and Maria de' Medici was a very important event. Cavalieri, who oversaw all major festivities of the house of Medici, was expected to direct this one as well. The conniving Caccini had him denied the position, and while Cavalieri did write some of the music, it was Caccini who managed the staging (we described this event here). The disappointed Cavalieri left Florence never to return. As for Peri, the stories are more comical. Upon learning that Peri was writing an opera, Euridice, for the wedding of Maria de' Medici to Henry IV, he rushed to compose his own version using the same libretto and had it published before the first performance of Peri’s work. That wasn’t all; Caccini’s daughter Francesca, a talented singer, was to participate in the performance of Peri’s Euridice. Even though Peri wrote the music for the whole opera, Caccini rewrote the parts performed by Francesca and several other singers under his command, all that just to spite Peri and promote himself. Francesca Caccini, by the way, turned into an excellent composer in her own right. Her opera, La liberazione di Ruggiero dall’isola d’Alcina (The Liberation of Ruggiero from the Island of Alcina) was just staged by the Chicago Haymarket Opera Company (yesterday was the last performance).

Even though Caccini wrote three operas, he’s better remembered for his collection of songs called Le nuove musiche (the New Music), published in 1602. Here are two songs from this collection, Amor, io parte and Alme luci beate, but the whole collection is wonderful. In this 1983 recording, the soprano is Montserrat Figueras, the wife of Jordi Savall, who accompanies her on the Viola da Gamba (Figueras died in 2011). Hopkinson Smith is playing the lute.Permalink

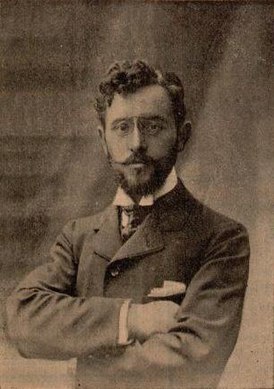

This Week in Classical Music: September 25, 2023. Florent Schmitt. We have to admit that we’re fascinated with the “bad boys” of music. They are invariably “boys,” as there are no “bad girls” in music historiography that we’re aware of. As for the male composers, there are plenty, Richard Wagner being the quintessential one. In the last couple of years, we’ve written about several of them, mostly the Germans in the 20th century, even though they are not the only ones: there were plenty of baddies in the Soviet bloc and, in a very different way, several Italians of the Renaissance. This week it’s Florent Schmitt’s turn, a French composer infamous for shouting “Vive Hitler!” during a concert. (Dmitri Shostakovich was also born this week, and, as talented as he was, he was no angel either, but we’ll return to Shostakovich another time). Schmitt was born on September 28th of 1870 in the town of Meurthe-et-Moselle, Lorraine, the area that was passing from France to Germany and back for centuries – thus the German name. At 17, he entered the conservatory in nearby Nancy, and two years later moved to Paris where he studied composition with Gabriel Fauré and Jules Massenet. While in Paris, Schmitt became friends with Frederick Delius, the English composer of German descent who was then living in Paris. In the 1890s he befriended Ravel and met Debussy.

girls” in music historiography that we’re aware of. As for the male composers, there are plenty, Richard Wagner being the quintessential one. In the last couple of years, we’ve written about several of them, mostly the Germans in the 20th century, even though they are not the only ones: there were plenty of baddies in the Soviet bloc and, in a very different way, several Italians of the Renaissance. This week it’s Florent Schmitt’s turn, a French composer infamous for shouting “Vive Hitler!” during a concert. (Dmitri Shostakovich was also born this week, and, as talented as he was, he was no angel either, but we’ll return to Shostakovich another time). Schmitt was born on September 28th of 1870 in the town of Meurthe-et-Moselle, Lorraine, the area that was passing from France to Germany and back for centuries – thus the German name. At 17, he entered the conservatory in nearby Nancy, and two years later moved to Paris where he studied composition with Gabriel Fauré and Jules Massenet. While in Paris, Schmitt became friends with Frederick Delius, the English composer of German descent who was then living in Paris. In the 1890s he befriended Ravel and met Debussy.

Schmitt tried to get the prestigious Prix de Rome five times, submitting five different compositions every year from 1896 to 1900, when he finally won it with the cantata Sémiramis. He spent three years in Rome and then traveled extensively, visiting Russia and North Africa, among other places. One of his most popular pieces composed during the period after Rome is the Piano Quintet op. 51 (1902-1908). Schmitt dedicated it to Fauré. Here’s the final movement, Animé, performed by the Stanislas Quartet with Christian Ivaldi at the piano. The ballet La tragédie de Salomé was composed during the same period, in 1907. Igor Stravinsky was taken by it; in Grove’s quote, he wrote to Schmitt: “I am only playing French music – yours, Debussy, Ravel’. And later, “I confess that [Salomé] has given me greater joy than any work I have heard in a long time.” In 1910 Schmitt created a concert version of the ballet. Here’s the second part of it (the New Philharmonia Orchestra is conducted by Antonio de Almeida). It’s not surprising that Stravinsky liked it, as it clearly presages parts of Rite of Spring. Another important piece, Psalm XLVII, was written in 1906.

During WWI Schmitt wrote music for military bands but returned to regular composing once the war was over. He also worked as a music critic for the newspaper Le Temps. Schmitt was a nationalist with pronounced sympathies toward the Nazi regime. The episode we referred to at the beginning of this entry happened in November of 1933. During a concert of the music of Kurt Weill, a Jewish composer who had beenrecently forced into exile by the Nazis, he stood up and shouted “Vive Hitler!” According to a witness, he added: “We already have enough bad musicians to have to welcome German Jews.” That makes him not only a Nazi sympathizer but also an antisemite. During the German occupation of France, Schmitt collaborated with the Vichy government and was a member of the Music section of the France-Germany Committee. He visited Germany and in December of 1941 went to Vienna to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Mozart’s death. After the liberation, Schmitt was investigated as a collaborator, but these proceedings were later dropped, although a year-long ban was imposed on performing and publishing his music. Soon after everything was forgotten and in 1952, just seven years after the end of the war, Schmitt was made the Commander of the Legion of Honor. In 1996, the controversial past of this "one of the most fascinating of France's lesser-known classical composers," as he’s often described, came into prominence again, and his name was removed from a school and a concert hall.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: September 18, 2023. Several conductors. We missed a lot of anniversaries while exploring the music of the transitional period between the Renaissance and early Baroque. Today we’ll get back to a group of conductors. First, Karl Böhm, one of the most successful of them. Böhm was born on August 28th of 1894 in Graz, Austria. His career took off in the 1920s, with some help from Bruno Walter; in 1927 Böhm was appointed the chief musical director in Darmstadt, and in 1931 he took the same position at the prestigious Hamburg Opera. In 1933 the Nazis came to power in Germany and Böhm took over the Dresden Semper Opera, after Fritz Busch, the previous director, went into exile. Böhm was a friend of Richard Strauss and conducted several premiers of his operas. In 1938 Böhm appeared at the Salzburg Festival, and in 1943 took over the famous Vienna opera. For many years Böhm was a Nazi sympathizer, though never a member of the NSDAP; after the war, he went through a two-year denazification period, and then his career took off again. He continued his engagements with Vienna and Dresden, conducted in South America, and made a very successful New York debut in 1957. He frequently led the Metropolitan, premiering operas by Berg and Strauss and successfully conducting many of Wagner’s operas (Birgit Nilsson debuted under Böhm’s baton). Böhm’s final engagements were in London, at Covent Garden and with the London Symphony. He died on August 14th of 1981, two weeks shy of his 87th birthday.

early Baroque. Today we’ll get back to a group of conductors. First, Karl Böhm, one of the most successful of them. Böhm was born on August 28th of 1894 in Graz, Austria. His career took off in the 1920s, with some help from Bruno Walter; in 1927 Böhm was appointed the chief musical director in Darmstadt, and in 1931 he took the same position at the prestigious Hamburg Opera. In 1933 the Nazis came to power in Germany and Böhm took over the Dresden Semper Opera, after Fritz Busch, the previous director, went into exile. Böhm was a friend of Richard Strauss and conducted several premiers of his operas. In 1938 Böhm appeared at the Salzburg Festival, and in 1943 took over the famous Vienna opera. For many years Böhm was a Nazi sympathizer, though never a member of the NSDAP; after the war, he went through a two-year denazification period, and then his career took off again. He continued his engagements with Vienna and Dresden, conducted in South America, and made a very successful New York debut in 1957. He frequently led the Metropolitan, premiering operas by Berg and Strauss and successfully conducting many of Wagner’s operas (Birgit Nilsson debuted under Böhm’s baton). Böhm’s final engagements were in London, at Covent Garden and with the London Symphony. He died on August 14th of 1981, two weeks shy of his 87th birthday.

Here is Richard Strauss’s Ein Heldenleben (A Hero's Life), a tone poem from 1898. Karl Böhm conducts the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. This recording was made in 1976. Also, quite recently we came across a DW documentary from 2022 called Music in Nazi Germany: The Maestro and the Cellist of Auschwitz (here). It’s very much worth watching. The maestro in question is not Karl Böhm but Wilhelm Furtwängler, eight years older than Böhm and more established. Still, much of what is said in the documentary about Furtwängler applies to Böhm (we think that to an even higher degree). A note: the “kapellmeister” of the Auschwitz women’s orchestra, Alma Rosé, mentioned in the documentary, died there in April of 1944. Alma was the daughter of Arnold Rosé, the concertmaster of the Vienna Philharmonic for 50 years and the leader of the famous Rosé Quartet. Alma’s mother was Gustav Mahler’s sister.

Just to list other conductors in our group: István Kertész (b. August 28, 1929); three conductors, born on September 1: Tullio Serafin (in 1878), Leonard Slatkin (in 1944), Seiji Ozawa, (in 1935). Christoph von Dohnányi was born on September 8, 1929, and Christopher Hogwood, on September 10, 1941.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: September 18, 2023. Several conductors. We missed a lot of anniversaries while exploring the music of the transitional period between the Renaissance and early Baroque. Today we’ll get back to a group of conductors. First, Karl Böhm, one of the most successful of them. Böhm was born on August 28th of 1894 in Graz, Austria. His career took off in the 1920s, with some help from Bruno Walter; in 1927 Böhm was appointed the chief musical director in Darmstadt, and in 1931 he took the same position at the prestigious Hamburg Opera. In 1933 the Nazis came to power in Germany and Böhm took over the Dresden Semper Opera, after Fritz Busch, the previous director, went into exile. Böhm was a friend of Richard Strauss and conducted several premiers of his operas. In 1938 Böhm appeared at the Salzburg Festival, and in 1943 took over the famous Vienna opera. For many years Böhm was a Nazi sympathizer, though never a member of the NSDAP; after the war, he went through a two-year denazification period, and then his career took off again. He continued his engagements with Vienna and Dresden, conducted in South America, and made a very successful New York debut in 1957. He frequently led the Metropolitan, premiering operas by Berg and Strauss and successfully conducting many of Wagner’s operas (Birgit Nilsson debuted under Böhm’s baton). Böhm’s final engagements were in London, at Covent Garden and with the London Symphony. He died on August 14th of 1981, two weeks shy of his 87th birthday.

early Baroque. Today we’ll get back to a group of conductors. First, Karl Böhm, one of the most successful of them. Böhm was born on August 28th of 1894 in Graz, Austria. His career took off in the 1920s, with some help from Bruno Walter; in 1927 Böhm was appointed the chief musical director in Darmstadt, and in 1931 he took the same position at the prestigious Hamburg Opera. In 1933 the Nazis came to power in Germany and Böhm took over the Dresden Semper Opera, after Fritz Busch, the previous director, went into exile. Böhm was a friend of Richard Strauss and conducted several premiers of his operas. In 1938 Böhm appeared at the Salzburg Festival, and in 1943 took over the famous Vienna opera. For many years Böhm was a Nazi sympathizer, though never a member of the NSDAP; after the war, he went through a two-year denazification period, and then his career took off again. He continued his engagements with Vienna and Dresden, conducted in South America, and made a very successful New York debut in 1957. He frequently led the Metropolitan, premiering operas by Berg and Strauss and successfully conducting many of Wagner’s operas (Birgit Nilsson debuted under Böhm’s baton). Böhm’s final engagements were in London, at Covent Garden and with the London Symphony. He died on August 14th of 1981, two weeks shy of his 87th birthday.

Here is Richard Strauss’s Ein Heldenleben (A Hero's Life), a tone poem from 1898. Karl Böhm conducts the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. This recording was made in 1976. Also, quite recently we came across a DW documentary from 2022 called Music in Nazi Germany: The Maestro and the Cellist of Auschwitz (here). It’s very much worth watching. The maestro in question is not Karl Böhm but Wilhelm Furtwängler, eight years older than Böhm and more established. Still, much of what is said in the documentary about Furtwängler applies to Böhm (we think that to an even higher degree). A note: the “kapellmeister” of the Auschwitz women’s orchestra, Alma Rosé, mentioned in the documentary, died there in April of 1944. Alma was the daughter of Arnold Rosé, the concertmaster of the Vienna Philharmonic for 50 years and the leader of the famous Rosé Quartet. Alma’s mother was Gustav Mahler’s sister.

leader of the famous Rosé Quartet. Alma’s mother was Gustav Mahler’s sister.

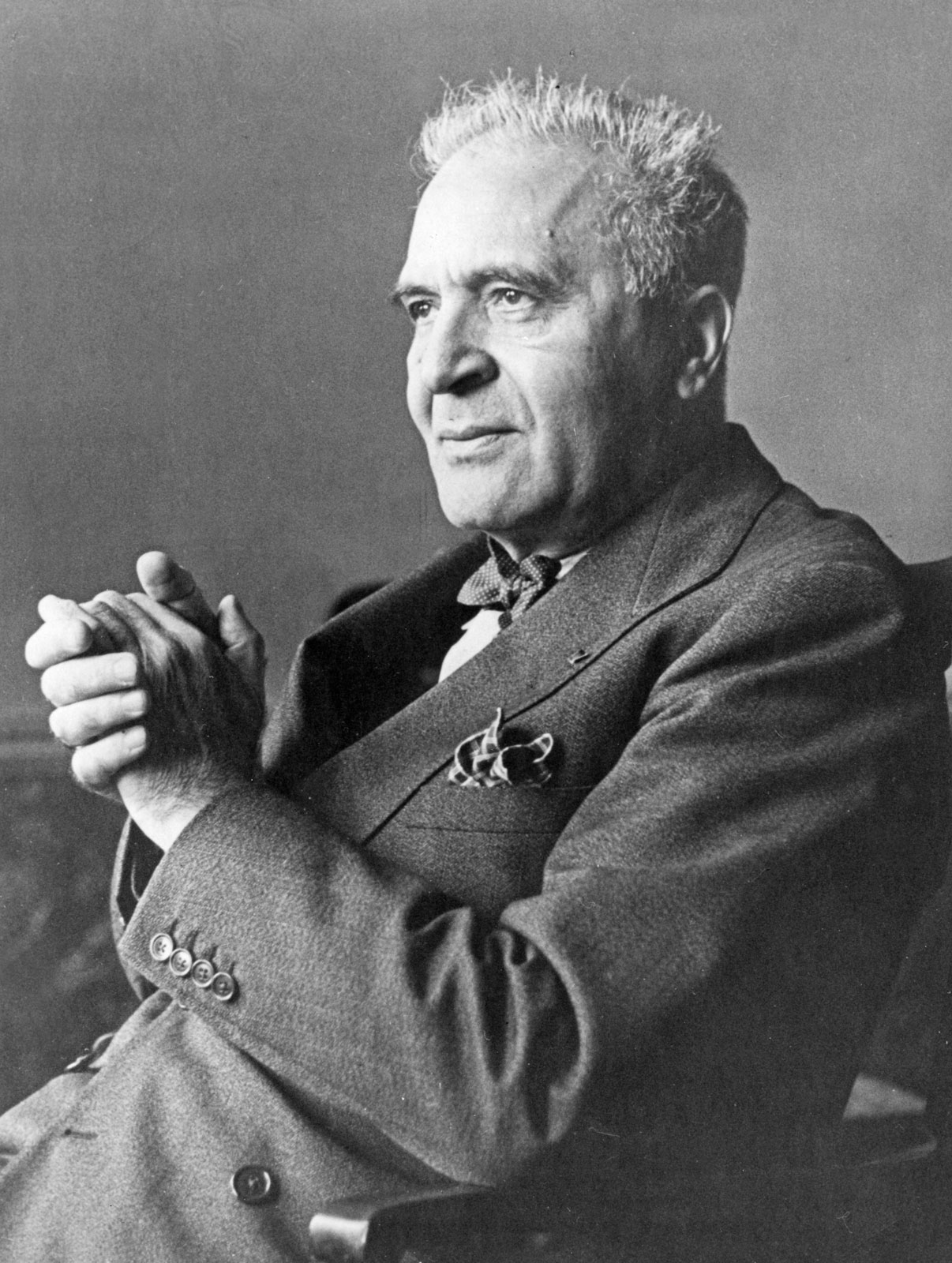

We mentioned Bruno Walter’s name above; he also happens to be one of the conductors we wanted to write about. Walter was born on September 15th of 1876 in Berlin. We celebrated him several years ago here. At least as talented as Böhm, his life couldn’t have been more different. Walter was Jewish, for many years he collaborated closely with Mahler and, in 1912, led the posthumous premier performance of the composer’s Ninth Symphony. He was the music director of the Bavarian State Opera in Munich, where he conducted most of Wagner’s operas. Walter escaped from Germany in 1933 (at the time he was the principal conductor of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra). After working in Europe, he moved to the US in 1939 and settled in Beverly Hills, the area that hosted a large German expat community. In the US, he worked with many orchestras, including the Chicago Symphony, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and the Philadelphia Orchestra. Bruno Walter was 85 when he died in 1962. Here Bruno Walter is playing the piano and conducting the NBC Symphony Orchestra in Mozart’s Piano Concerto no. 20. This is a live recording made on November 3rd of 1939.

Just to list other conductors in our group: István Kertész (b. August 28, 1929); three conductors, born on September 1: Tullio Serafin (in 1878), Leonard Slatkin (in 1944), Seiji Ozawa, (in 1935). Christoph von Dohnányi was born on September 8, 1929, and Christopher Hogwood, on September 10, 1941.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: September 11, 2023. Transitions. For the last four weeks, we were preoccupied with two Florentine composers, Emilio de' Cavalieri and Jacopo Peri. In a way, this is unusual, as neither of them was what we would call “great,” as were, for example, Tomás Luis de Victoria, just two years older than Cavalieri, or Giovanni Gabrieli, born sometime between Cavalieri and Peri. But somehow the Florentines became instrumental in furthering one of the great shifts in classical music, from polyphony to monody of the early Baroque. This is a fascinating topic in itself: How could the relatively simplistic works of Cavalieri and Peri replace the grand and sophisticated music of the High Renaissance? How could such stunning works as Victoria’s Funeral Mass or Gabrieli’s In Ecclesiis fall out of favor while the first rather clumsy attempts at opera became all the rage? As far as we can tell, Baroque music, as interesting as it was in its early phases, didn’t reach the level of Palestrina or Orlando di Lasso till the late 17th century and into the 18th, when Handel and Bach composed their masterpieces. This introduces another great example: Johann Sebastian Bach, who, in his later years, was considered old-fashioned, past his time; his great Mass in B minor was completed in 1749, a year before his death, when the music of his son, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, was much more popular. The first public performance of the Mass had to wait for more than 100 years (the history of St. Matthew Passion was similar). In the meantime, composers of the Mannheim school, nearly forgotten now, were working at the court with the best orchestra in Europe and developing, unknowingly, the style that would bring us, several decades later, the symphonies of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. The “not-so-greats” leading the way, leaving the greats behind but paving the way for a new generation of supreme talents…

way, this is unusual, as neither of them was what we would call “great,” as were, for example, Tomás Luis de Victoria, just two years older than Cavalieri, or Giovanni Gabrieli, born sometime between Cavalieri and Peri. But somehow the Florentines became instrumental in furthering one of the great shifts in classical music, from polyphony to monody of the early Baroque. This is a fascinating topic in itself: How could the relatively simplistic works of Cavalieri and Peri replace the grand and sophisticated music of the High Renaissance? How could such stunning works as Victoria’s Funeral Mass or Gabrieli’s In Ecclesiis fall out of favor while the first rather clumsy attempts at opera became all the rage? As far as we can tell, Baroque music, as interesting as it was in its early phases, didn’t reach the level of Palestrina or Orlando di Lasso till the late 17th century and into the 18th, when Handel and Bach composed their masterpieces. This introduces another great example: Johann Sebastian Bach, who, in his later years, was considered old-fashioned, past his time; his great Mass in B minor was completed in 1749, a year before his death, when the music of his son, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, was much more popular. The first public performance of the Mass had to wait for more than 100 years (the history of St. Matthew Passion was similar). In the meantime, composers of the Mannheim school, nearly forgotten now, were working at the court with the best orchestra in Europe and developing, unknowingly, the style that would bring us, several decades later, the symphonies of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. The “not-so-greats” leading the way, leaving the greats behind but paving the way for a new generation of supreme talents…

Yet again we don’t have the time to properly acknowledge the composers born this week (among them are Arnold Schoenberg and Girolamo Frescobaldi, and also Arvo Pärt, Clara Schumann and William Boyce, who, like Beethoven, went deaf but continued, for a while, to compose and play the organ). We wanted to go back a month and commemorate some of the composers born during that time: too many to mention, but two of them, Henry Purcell and Antonin Dvorak, were born last week. And of course, we’ve missed a lot of performers and conductors, among whom were the pianists Aldo Ciccolini and Maria Yudina, Ginette Neveu (violin) and William Primrose (viola), the singers Kathleen Battle and Angela Gheorghiu, and conductors Wolfgang Sawallisch and Karl Böhm. Till next time, then.Permalink