Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

This Week in Classical Music: June 19, 2023. Mid-18th Century Music, Watts, and two Conductors. Johann Stamitz, a Bohemian composer and the founder of the so-called Mannheim school, which, with its sudden crescendos and diminuendos, became very popular in the middle of the 18th century, was born on June 18th of 1717. The mid-18th century was a bit short on major talent unless you count Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach who was about three years older than Stamitz (we’re not big fans of CPE Bach but we understand that many people are). Johann Sebastian Bach died in 1750, George Frideric Handel – in 1759, but their music had went out of vogue many years earlier. Domenico Scarlatti, born like the previous two in 1685, was living in Madrid and by then mostly engaged in copying and editing his numerous sonatas; in any event, his output wasn’t well known outside of Spain. In 1750 Joseph Haydn was only 18, so of the living composers there were Telemann, who was getting old and not as productive as in his prodigious youth, and minor stars like Johann Friedrich Fasch and Johann Joachim Quantz. The opera was faring better: Rameau still reigned on the music scene in Paris, and Christoph Willibald Gluck, born the same years as CPE Bach, while not yet on the level of Orfeo ed Euridice, was dispatching operas at the rate of a couple a year. The world had yet to wait for Haydn to develop and for Mozart to appear.

school, which, with its sudden crescendos and diminuendos, became very popular in the middle of the 18th century, was born on June 18th of 1717. The mid-18th century was a bit short on major talent unless you count Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach who was about three years older than Stamitz (we’re not big fans of CPE Bach but we understand that many people are). Johann Sebastian Bach died in 1750, George Frideric Handel – in 1759, but their music had went out of vogue many years earlier. Domenico Scarlatti, born like the previous two in 1685, was living in Madrid and by then mostly engaged in copying and editing his numerous sonatas; in any event, his output wasn’t well known outside of Spain. In 1750 Joseph Haydn was only 18, so of the living composers there were Telemann, who was getting old and not as productive as in his prodigious youth, and minor stars like Johann Friedrich Fasch and Johann Joachim Quantz. The opera was faring better: Rameau still reigned on the music scene in Paris, and Christoph Willibald Gluck, born the same years as CPE Bach, while not yet on the level of Orfeo ed Euridice, was dispatching operas at the rate of a couple a year. The world had yet to wait for Haydn to develop and for Mozart to appear.

Let’s hear one of Johann Stamitz’s symphonies, this one in A major, the so-called “Mannheim no. 2”. Taras Demchyshyn conducts what seems to be mostly the Ukrainian Hibiki Strings ensemble of Japan.

The American composer André Watts was born on June 20th of 1946 in Nuremberg. Watts’s mother was Hungarian and his father – an African-American NCO serving in Germany. Watts spent his childhood in different American military posts in Europe. He started his musical lessons studying the violin and later switched to the piano. At around nine, Watts went to the US and enrolled at the Philadelphia Musical Academy. His breakthrough came in 1963 when he played Liszt’s First Piano Concerto with the New York Philharmonic under the direction of Leonard Bernstein. He later studied with Leon Fleisher at the Peabody Conservatory. From an early age, Watts had a prodigious technique, and his musicianship grew with experience (and studies with Fleisher). His repertoire, while mostly Romantic, was broad. For many years he taught at the Jacobs School of Music of Indiana University. Here’s the 1963 recording of Liszt’s Piano Concerto no. 1 with the NYPO and Leonard Bernstein.

Two conductors were born this week, Hermann Scherchen on June 21st of 1891 in Berlin, and James Levine, on June 23rd of 1943 in Cincinnati. Scherchen was one of the more adventuresome German conductors: he promoted the music of Schoenberg, Berg, and Hindemith after WWI, and conducted Mahler’s symphonies when very few did so. After WWII he was active at Darmstadt and championed the music of Dallapiccola, Henze, and other young composers. He was the first to conduct parts of Schoenberg’s Moses and Aaron.

James Levine was probably the most talented conductor to ever lead the Metropolitan Opera. His place in the musical history of the US would’ve been very different were it not for a sex scandal that broke out in 2017. We’ll dedicate an entry to him shortly.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: June 12, 2023. Maher’s 9th at the CSO. Jakub Hrůša, a Czech conductor, came to Chicago to perform one work, Mahler’s Ninth, his last completed symphony. Any performance of this work by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra is an event, and so was the concert this past Thursday. The CSO doesn’t play the Ninth often: the last performance at the Symphony Center was five years ago, under the direction of Esa-Pekka Salonen, a wonderful Finnish conductor and the current San Francisco Symphony music director. But we vividly remember it being played in December of 1995 when Pierre Boulez led the orchestra in a profound reading. Boulez and the CSO then recorded it at Medinah Temple and received a Grammy for it. Those were the times when Grammys were worth something. By the way, Riccardo Muti, the outgoing Music Director, has never conducted this symphony, or, as far as we know, any other of Mahler’s, except for his youthful no. 1.

Any performance of this work by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra is an event, and so was the concert this past Thursday. The CSO doesn’t play the Ninth often: the last performance at the Symphony Center was five years ago, under the direction of Esa-Pekka Salonen, a wonderful Finnish conductor and the current San Francisco Symphony music director. But we vividly remember it being played in December of 1995 when Pierre Boulez led the orchestra in a profound reading. Boulez and the CSO then recorded it at Medinah Temple and received a Grammy for it. Those were the times when Grammys were worth something. By the way, Riccardo Muti, the outgoing Music Director, has never conducted this symphony, or, as far as we know, any other of Mahler’s, except for his youthful no. 1.

Jakub Hrůša is 41 years old and somewhat of a late-rising star. After conducting several orchestras in his native Czech Republic for several years, in 2016 he was made the chief conductor of the Bamberg Symphony, one of Germany’s better orchestras. The following year he was appointed as one of two principal guest conductors of the Philharmonia Orchestra, London. In 2021 he was made the principal guest conductor of the Orchestra of the Accademia di Santa Cecilia in Rome. Hrůša’s big break came in 2022, when he was appointed the music director designate of the Royal Opera House (the Covent Garden), with the formal appointment as Music Director coming in 2025.

orchestras in his native Czech Republic for several years, in 2016 he was made the chief conductor of the Bamberg Symphony, one of Germany’s better orchestras. The following year he was appointed as one of two principal guest conductors of the Philharmonia Orchestra, London. In 2021 he was made the principal guest conductor of the Orchestra of the Accademia di Santa Cecilia in Rome. Hrůša’s big break came in 2022, when he was appointed the music director designate of the Royal Opera House (the Covent Garden), with the formal appointment as Music Director coming in 2025.

But what about the performance in Chicago? We want to preface our brief assessment with this: we think that no performance by a major orchestra can be bad these days (this was not the case 40 years ago). What we mean is that Mahler’s music contains so much material, both at any given moment and in temporal relation to each other, that even if certain episodes are not done very well, there’s still an enormous amount of substance to overwhelm the listener. For example, under Hrůša’s baton, the opening bars and the first “breathing theme” of the first movement (Andante Comodo) sounded a bit disjointed – maybe nerves and the fact that it was the first of three performances, but it didn’t matter much as things settled down quickly and proceeded wonderfully. The second movement, a series of rustic dances, and the third, Rondo-Burleske, were nervy, sardonic, and at times violent, altogether very well played. We have some qualms with the magnificent final Adagio marked Sehr langsam und noch zurückhaltend (very slowly and reserved). Everything was in place, but somehow not revelatory. This was good, but “good” is not exactly what one expects from this music: Boulez’s finale broke one’s heart. Maybe it’s his younger age and Hrůša will eventually go deeper. The public rewarded the conductor and the musicians with prolonged and enthusiastic applause. The gracious Hrůša went around the orchestra, thanking all the principal players, and then patted the score, indicating the most important element of the proceedings. We thought that to be a very proper gesture: even though the orchestra’s playing was excellent and Hrůša’s interpretation fine, it was Mahler’s genius that made the evening so memorable.

A couple of extraneous points. The Orchestra Hall was full, which is great, considering that Hrůša isn’t that well known in Chicago. As expected, no reviews were published in the major newspapers. Larry Johnson published a nice one in his Chicago Classical Review. And, despite some quibbles, we would be happy if Jakub Hrůša became Muti’s successor.Permalink

The great German Romantic composer Robert Schumann was born on June 8th of 1810, Richard Strauss – on June 11th of 1864. Several other names among the composers born this week: Tomaso Albinoni, once thought of as an equal to Corelli and Vivaldi, on Jun 8th of 1671. Carl Nielsen, Denmark’s by far most famous composer, on June 9th of 1865. The Soviet-Armenian Aram Khachaturian, whose ballets Spartacus and Gayane are still regularly staged in Russia, was born in Tiflis, now Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, on June 6th of 1903 (in those years Tiflis boasted a large Armenian community). Erwin Schulhoff, the Jewish composer, was born in Prague into a German-speaking family on June 18th of 1894. His fate was tragic: his 1941 desperate attempt to escape to the Soviet Union failed; he was

The great German Romantic composer Robert Schumann was born on June 8th of 1810, Richard Strauss – on June 11th of 1864. Several other names among the composers born this week: Tomaso Albinoni, once thought of as an equal to Corelli and Vivaldi, on Jun 8th of 1671. Carl Nielsen, Denmark’s by far most famous composer, on June 9th of 1865. The Soviet-Armenian Aram Khachaturian, whose ballets Spartacus and Gayane are still regularly staged in Russia, was born in Tiflis, now Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, on June 6th of 1903 (in those years Tiflis boasted a large Armenian community). Erwin Schulhoff, the Jewish composer, was born in Prague into a German-speaking family on June 18th of 1894. His fate was tragic: his 1941 desperate attempt to escape to the Soviet Union failed; he was arrested, imprisoned in Bavaria, and died there of tuberculosis in 1942. Schulhoff went through many phases in his life and composed in many styles; his musical progression is quite unique: he started composing atonal pieces, then moved to the Dada, then Romantic, and then, finally (and incredibly) the Social Realism. A couple of years ago we promised to dedicate an entry to him but we’re still not there yet. In the meantime, here is Schulhoff’s Piano Concerto no. 2 (concerto with a chamber orchestra). The pianist is Dominic Cheli; RVC Ensemble is conducted by James Conlon.

arrested, imprisoned in Bavaria, and died there of tuberculosis in 1942. Schulhoff went through many phases in his life and composed in many styles; his musical progression is quite unique: he started composing atonal pieces, then moved to the Dada, then Romantic, and then, finally (and incredibly) the Social Realism. A couple of years ago we promised to dedicate an entry to him but we’re still not there yet. In the meantime, here is Schulhoff’s Piano Concerto no. 2 (concerto with a chamber orchestra). The pianist is Dominic Cheli; RVC Ensemble is conducted by James Conlon.

This Week in Classical Music: June 5, 2023. Schumann and much more. First thing, today is Martha Argerich’s 82nd birthday. Happy Birthday, Martha!

Then there are two conductors, Klaus Tennstedt and George Szell. Szell, born on June 7th of 1897, is considered one of the greatest conductors of the 20th century. We published an entry about him a couple of years ago. Klaus Tennstedt was born on June 6th of 1926 in Merseburg, in the eastern part of Germany which, after WWII, became the GDR. He studied at the Leipzig Conservatory and, in 1958, became the director of the Dresden opera. Tennstedt emigrated from East Germany in 1971. First, he settled in Sweden, where he conducted the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra but a year later moved to West Germany. Tennstedt guest-conducted all major US orchestras and many in Europe, including the Berlin Philharmonic and the Concertgebouw. He was closely associated with two London orchestras, the London Symphony, and London Philharmonic. He became the principal conductor of the latter in 1987. Tennstedt’s interpretations of the music of Mahler were highly acclaimed. Here is the majestic Finale of Mahler’s Symphony no. 3 with the London Philharmonic.

And let’s not forget about Gaetano Berenstadt, a favorite alto-castrato of George Frideric Handel. He was born in Florence on June 6th of 1687. His parents were German, serving at the court of the Duke of Tuscany. Berenstadt first appeared in London in 1717, singing in the operas by Handel, Scarlatti and Ariosti. He then moved to Germany and back to Italy, returning to London in 1722 to join Handel’s Royal Academy of Music. He sang in several of Handel’s operas, including Giulio Cesare, Flavio, and Ottone. Berenstadt returned to Italy for good in 1726; he sang in Rome and Florence for another six years. In bad health for the last few years, he died in Florence at the age of 47.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: May 29, 2023. Warmly, but without much enthusiasm. Erich Wolfgang Korngold was born on this day in 1897. A child prodigy, he had a fascinating, and in many ways difficult life that spanned several epochs. He was born in Brünn, Austria-Hungary, now Brno, the Czech Republic, at the end of the Empire’s culturally brilliant era, which was open enough to allow the assimilated Jews to flourish. A child prodigy, he was a darling of Vienna, where the family moved when Erich was four. His father, Julius Korngold, was the most prominent music critic of the time, working for the newspaper Neue Freie Presse, the New York Times of Vienna. Erich’s first piano sonata was composed at the age of 11; another piano and a violin sonata followed shortly after, then a Sinfonietta and a couple of short operas. World War I ended with the disappearance of Austria-Hungary, and Vienna, the capital of a world power and a cultural center of the world turned into a provincial Middle-European city. Korngold, by then in his early 20s, turned to the opera. Die Tote Stadt (The Dead City), composed in 1920 when Korngold was 23, was a tremendous success and staged all over Germany, then Europe, even reaching the Met two years later. In the meantime, Korngold turned to writing and arranging operettas. They were very popular and brought in quite a bit of money. His father, whose idol was Gustav Mahler and who didn’t care much for operettas, wasn’t pleased, considering this a waste of his son’s talent. In retrospect, the technique of writing lighter music with lots of words thrown in became an asset when Erich earned money in Hollywood writing music scores some years later.

many ways difficult life that spanned several epochs. He was born in Brünn, Austria-Hungary, now Brno, the Czech Republic, at the end of the Empire’s culturally brilliant era, which was open enough to allow the assimilated Jews to flourish. A child prodigy, he was a darling of Vienna, where the family moved when Erich was four. His father, Julius Korngold, was the most prominent music critic of the time, working for the newspaper Neue Freie Presse, the New York Times of Vienna. Erich’s first piano sonata was composed at the age of 11; another piano and a violin sonata followed shortly after, then a Sinfonietta and a couple of short operas. World War I ended with the disappearance of Austria-Hungary, and Vienna, the capital of a world power and a cultural center of the world turned into a provincial Middle-European city. Korngold, by then in his early 20s, turned to the opera. Die Tote Stadt (The Dead City), composed in 1920 when Korngold was 23, was a tremendous success and staged all over Germany, then Europe, even reaching the Met two years later. In the meantime, Korngold turned to writing and arranging operettas. They were very popular and brought in quite a bit of money. His father, whose idol was Gustav Mahler and who didn’t care much for operettas, wasn’t pleased, considering this a waste of his son’s talent. In retrospect, the technique of writing lighter music with lots of words thrown in became an asset when Erich earned money in Hollywood writing music scores some years later.

In 1933 the Nazis came to power in Germany and banned Korngold’s music in that country (after the Anschluss, it would be banned in Austria too). In 1934, an invitation from Max Reinhardt, the famous German theater director, who was then working in New York theaters and trying his hand at film, brought Korngold to Hollywood. Nobody in the US was much interested in Korngold’s more “serious” music but his career in the movies took off. He wrote music for some of the most popular films of the 1930s, such as Captain Blood, The Adventures of Robin Hood, and many others, singlehandedly creating a new musical genre. He did write some “serious” music as well, but not much of it: the Violin Concerto in 1945 and a large-scale symphony in 1947, which used themes from his 1939 film The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex. These works are romantic, flowery, and pretty, but they sound rather dated – and, not surprisingly, remind one of his film music. We’re afraid that we agree with Julius Korngold that Erich, with all his obvious talents and tremendous promise, didn’t go “deep” enough. But maybe it was just inherently not in his nature: if you listen to his Sinfonietta, composed when Erich was 16, you can already hear the theatricality of Robin Hood.

Marin Marais was born on June 1st of 1653 in Paris. A student of Jean-Baptiste Lully, he became famous after the film Tous les matins du monde, featuring his music, premiered in 1991. We find most of it repetitive and not very imaginative (somehow the repetitious phrases in the music of Padre Antonio Soler work much better).

Mikhail Glinka, also born on June 1st but in 1804, is widely considered the father of Russian classical music and to that extent, is important. And Edward Elgar was born on June 2nd of 1857. He’s one of the most significant English composers of the modern era, but we’ve already confessed to being rather cool to his music, the Cello concerto in the interpretation of Jacqueline du Pré notwithstanding.Permalink

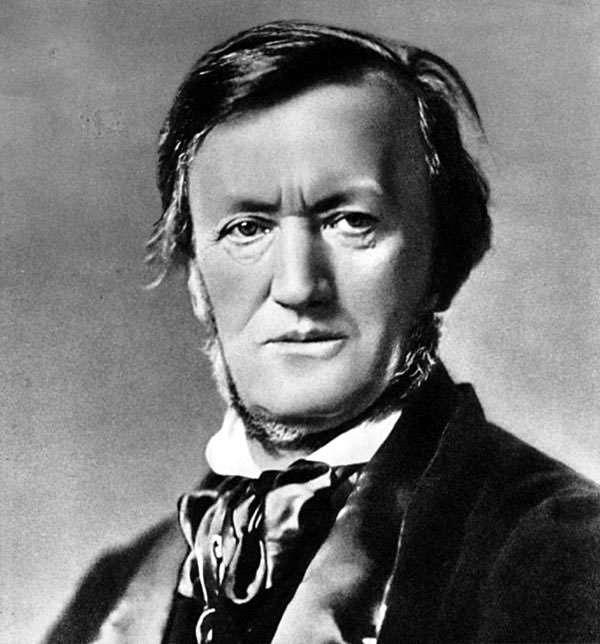

This Week in Classical Music: May 22, 2023. Wagner. These days when one says “Wagner” the first assumption is that the person is talking about the Russian military group fighting in Ukraine on behalf of the Russian government. The image of the great German composer comes in second. It is not clear why the Russian nationalistic paramilitary organization took such a Western name. As one theory goes, the original founder of the organization, one Dmitry Utkin, a neo-Nazi interested in the history of the Third Reich, took the call sign of Wagner, after Richard Wagner, Adolph Hitler’s favorite composer. This is almost too much: Richard Wagner had enough problems of his own doing to be associated with this murderous group.

Ukraine on behalf of the Russian government. The image of the great German composer comes in second. It is not clear why the Russian nationalistic paramilitary organization took such a Western name. As one theory goes, the original founder of the organization, one Dmitry Utkin, a neo-Nazi interested in the history of the Third Reich, took the call sign of Wagner, after Richard Wagner, Adolph Hitler’s favorite composer. This is almost too much: Richard Wagner had enough problems of his own doing to be associated with this murderous group.

Richard Wagner was born on May 22nd of 1813 in Leipzig. That he is a composer of genius goes without saying. That he was a rabid and active antisemite is also very clear. This gets us into a very complicated predicament: what do we do about an evil genius? Do we ignore all the “extraneous” biographical facts and just concentrate on the quality of his music? Or do we, as the Israelis have done, ban his music altogether? We don’t have an answer. A litmus test, suggested by some thinkers, goes like this: if the aspects of the creator’s philosophy, in this case, his antisemitism, have directly affected his works, then we cannot ignore them. If, on the other hand, they did not, then maybe we should concentrate on the work itself and ignore the rest while letting biographers dig into the sordid details. Even given this test we don’t quite know how to qualify Wagner’s work. Wagner’s writings are full of antisemitism, but clearly, they are not what he’s famous for – there were too many antisemites in Germany during his time. His opera Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg has a whiff of antisemitism while most other operas are free of it. We’re not going to solve this problem today, so just to confirm that we’re talking about a flawed genius, let’s listen to the Prelude to Act I of Parsifal, Wagner’s last opera. This is from the 1972 recording made by Sir Georg Solti and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. This amazing recording also features René Kollo, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Christa Ludwig, all at the top of their form. Wagner prohibited any performances of Parsifal outside of Bayreuth, and that’s how it was for the first 20 years after the premiere. Even though Wagner died in 1883, his widow Cosima, Liszt’s daughter and also an antisemite, wouldn’t allow any other staging. Then, in 1903, a court decided that the Metropolitan Opera could perform Parsifal in New York. Cosima banned all singers who participated in that performance from ever appearing in Bayreuth. Only in 1914 was the ban lifted and immediately 50 opera houses presented it all over Europe. Since then, Parsifal has remained on the stage of all major opera theaters around the world.

PermalinkThis Week in Classical Music: May 15, 2023. Monteverdi and Goldmark. One of our all-time favorite composers, Claudio Monteverdi, was born (or at least baptized) in Cremona on this day in 1567. A seminal figure in European music history, he spanned two traditions, the old, Renaissance, and the new, Baroque, and in the process created the new art of opera. We’ve written about him many times, so today we’ll just present one section, Laudate pueri, from his Vespro della Beata Vergine (Vespers for the Blessed Virgin), also known as his 1610 Vespers. Monteverdi composed the Vespers while in Mantua, at the court of the Gonzagas. It was published in Venice and dedicated to Pope Paul V, famous for his friendship and support of Galileo Galilei (but also for nepotism: he made his nephew, Cardinal Scipione Borghese so rich that it allowed Scipione to start what is now known as the Borghese Collection of paintings and sculptures). Back to the music, though: here is Laudate pueri, performed by the British ensemble The Sixteen under the direction of their founder, Harry Christophers.

1567. A seminal figure in European music history, he spanned two traditions, the old, Renaissance, and the new, Baroque, and in the process created the new art of opera. We’ve written about him many times, so today we’ll just present one section, Laudate pueri, from his Vespro della Beata Vergine (Vespers for the Blessed Virgin), also known as his 1610 Vespers. Monteverdi composed the Vespers while in Mantua, at the court of the Gonzagas. It was published in Venice and dedicated to Pope Paul V, famous for his friendship and support of Galileo Galilei (but also for nepotism: he made his nephew, Cardinal Scipione Borghese so rich that it allowed Scipione to start what is now known as the Borghese Collection of paintings and sculptures). Back to the music, though: here is Laudate pueri, performed by the British ensemble The Sixteen under the direction of their founder, Harry Christophers.

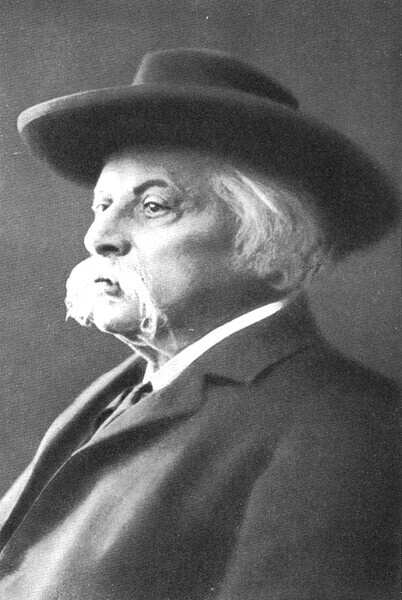

Carl Goldmark is almost forgotten, but in his day, he was one of the most popular composers in the German-speaking world. His opera Die Königin von Saba (The Queen of Sheba) was performed continuously from the day it successfully premiered in 1875 in Vienna’s Hofoper, till 1938, when Austria was taken over by the Nazis in the so-called Anschluss. Goldmark was born on May 18th of 1830 in Keszthely, a Hungarian town in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Goldmark was Jewish (his father was a cantor in the local synagogue); the family came from Galicia, and Goldmark’s first language was Yiddish – he never spoke Hungarian and learned German as a teenager. Goldmark studied the violin in Vienna and later supported himself by playing the instrument in various local orchestras. Around this time, he accepted the German culture as his own, which was the path for many upwardly mobile Jews in Austria and Germany in the second half of the 19th century. Around 1862 he became friends with Johannes Brahms, who had recently moved to Vienna from Hamburg. Goldmark’s first successful composition was a concert overture Sakuntala, based on the Indian epic Mahabharata, which premiered in 1865. Goldmark followed it with another exotic composition, the above-mentioned opera Die Königin von Saba. It was a spectacular success and performances of the opera were mounted internationally. Goldmark became part of the establishment, receiving prizes and honors, and presiding over important musical juries. His 70th and 80th birthdays were celebrated nationally with great pomp. He helped Mahler get his appointment at the Court Opera in 1897; some years later, he did a similar favor to Arnold Schoenberg, who was seeking an appointment to the Imperial Academy of Music and Arts. Goldmark died several months into WWI, grieving the loss of his grandchild who was killed in one of the first actions in Serbia.

performed continuously from the day it successfully premiered in 1875 in Vienna’s Hofoper, till 1938, when Austria was taken over by the Nazis in the so-called Anschluss. Goldmark was born on May 18th of 1830 in Keszthely, a Hungarian town in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Goldmark was Jewish (his father was a cantor in the local synagogue); the family came from Galicia, and Goldmark’s first language was Yiddish – he never spoke Hungarian and learned German as a teenager. Goldmark studied the violin in Vienna and later supported himself by playing the instrument in various local orchestras. Around this time, he accepted the German culture as his own, which was the path for many upwardly mobile Jews in Austria and Germany in the second half of the 19th century. Around 1862 he became friends with Johannes Brahms, who had recently moved to Vienna from Hamburg. Goldmark’s first successful composition was a concert overture Sakuntala, based on the Indian epic Mahabharata, which premiered in 1865. Goldmark followed it with another exotic composition, the above-mentioned opera Die Königin von Saba. It was a spectacular success and performances of the opera were mounted internationally. Goldmark became part of the establishment, receiving prizes and honors, and presiding over important musical juries. His 70th and 80th birthdays were celebrated nationally with great pomp. He helped Mahler get his appointment at the Court Opera in 1897; some years later, he did a similar favor to Arnold Schoenberg, who was seeking an appointment to the Imperial Academy of Music and Arts. Goldmark died several months into WWI, grieving the loss of his grandchild who was killed in one of the first actions in Serbia.

Goldmark’s Violin Concerto no. 1 was composed in 1877. It’s a wonderful composition, rarely performed these days. Here is a marvelous recording made by Nathan Milstein in 1957. Harry Blech conducts the Philharmonia Orchestra. We wonder why it’s not being played more often.Permalink