Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

This Week in Classical Music: March 27, 2023. Rachmaninov 150. One day of this week is very special: April 1st marks the 150th anniversary of the great Russian composer, pianist, and conductor, Sergei Rachmaninov (some outlets were celebrating his birthday on the 20th of March, as that was his birthdate according to the old Russian Julian calendar, but this is like observing the Russian Revolution on October 25th, rather than the conventional November 7th). We’re not going to trace Rachmaninov’s life; suffice it to say that it was divided into two irreconcilable parts, one, from his birth till the Russian Revolution, and then, from 1918, emigration and life in the United States. In terms of his creative output, these two parts are incomparable. The vast majority of his compositions were created while Rachmaninov lived in Russia: his piano pieces, such as the Études-Tableaux and the Preludes, the first three Piano concertos, two symphonies and Isle of the Dead, the Second piano sonata (the first one was a juvenile piece), the early operas, most of his songs, the choral works, such as The Bells and the All-Night Vigil – all of these were written in Russia. In America Rachmaninov had to earn his living by playing piano and conducting, with very little time left for composing. All he wrote while in America were (not counting several miscellaneous pieces) a not-very-successful Piano Concerto no. 4, Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Symphony no. 3, Variations on a Theme of Corelli, and Symphonic Dances. We’ve always wondered if one could explain such a tremendous disparity just by Rachmaninov’s need to earn money by performing. We suspect there was more to it, but this is not the place to address this issue.

conductor, Sergei Rachmaninov (some outlets were celebrating his birthday on the 20th of March, as that was his birthdate according to the old Russian Julian calendar, but this is like observing the Russian Revolution on October 25th, rather than the conventional November 7th). We’re not going to trace Rachmaninov’s life; suffice it to say that it was divided into two irreconcilable parts, one, from his birth till the Russian Revolution, and then, from 1918, emigration and life in the United States. In terms of his creative output, these two parts are incomparable. The vast majority of his compositions were created while Rachmaninov lived in Russia: his piano pieces, such as the Études-Tableaux and the Preludes, the first three Piano concertos, two symphonies and Isle of the Dead, the Second piano sonata (the first one was a juvenile piece), the early operas, most of his songs, the choral works, such as The Bells and the All-Night Vigil – all of these were written in Russia. In America Rachmaninov had to earn his living by playing piano and conducting, with very little time left for composing. All he wrote while in America were (not counting several miscellaneous pieces) a not-very-successful Piano Concerto no. 4, Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Symphony no. 3, Variations on a Theme of Corelli, and Symphonic Dances. We’ve always wondered if one could explain such a tremendous disparity just by Rachmaninov’s need to earn money by performing. We suspect there was more to it, but this is not the place to address this issue.

That Rachmaninov was one of the greatest pianists of the 20th century is accepted by practically everybody. But what about his compositions? He’s one of the most popular composers ever, if one judges by the number of his pieces being performed and broadcasted, the Piano concertos nos. 2 and 3 and Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini in particular. But was he a great composer? Here opinions differ. Clearly, he wasn’t an innovator, but not all great composers were: we recently talked about Bach, whose music was considered outdated by many of his contemporaries. Eric Blom, a famous music critic and the editor of the 5th edition of Grove's Dictionary of Music, was one of the skeptics. He wrote that the composer “did not have the individuality of Taneyev or Medtner. Technically he was highly gifted, but also severely limited. His music is ... monotonous in texture ... The enormous popular success some few of Rakhmaninov's works had in his lifetime is not likely to last, and musicians never regarded it with much favour.” This seems to be both wrong and unfair, and Harold Schonberg, the chief music critic of the New York Times, responded (in his book on great composers) in kind: “It is one of the most outrageously snobbish and even stupid statements ever to be found in a work that is supposed to be an objective reference.” We have to confess that sometimes, listening to somewhat shallow, formulaic passages that appear quite often in many of Rachmaninov’s pieces, we have our doubts. But that’s not the way to judge any creative artist: it should be done by what he did best, and Rachmaninov did write brilliant music. That’s what will keep him in the pantheon of composers of the first half of the 20th century.

Let’s listen to some music. First, Sviatoslav Richter plays two of Rachmaninov’s Etudes-Tableaux op.33: no. 5 and no. 6, but from 1911. And here Richter again, in Prelude no. 10, from op. 32, composed a year earlier, in 1910. And finally, a sample of Rachmaninov’s late symphonic work: from 1940, his Symphonic Dances. Vladimir Ashkenazy leads the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra.Permalink

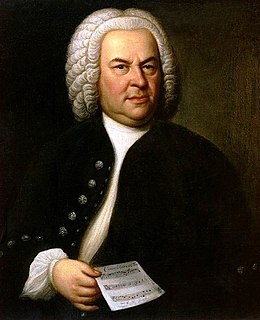

This Week in Classical Music: March 20, 2023. Bach and Four Pianists. Johann Sebastian Bach was born on March 21st of 1685 in Eisenach. Four pianists were also born this week; we’ll present them briefly and then have them play several of Bach’s works. A word on dating Bach’s compositions: even though we know a lot about his life, the dating of his output is very approximate, so sometimes it’s not clear where Bach was when he wrote some of the pieces. Different sources often provide different dates and estimate ranges.

present them briefly and then have them play several of Bach’s works. A word on dating Bach’s compositions: even though we know a lot about his life, the dating of his output is very approximate, so sometimes it’s not clear where Bach was when he wrote some of the pieces. Different sources often provide different dates and estimate ranges.

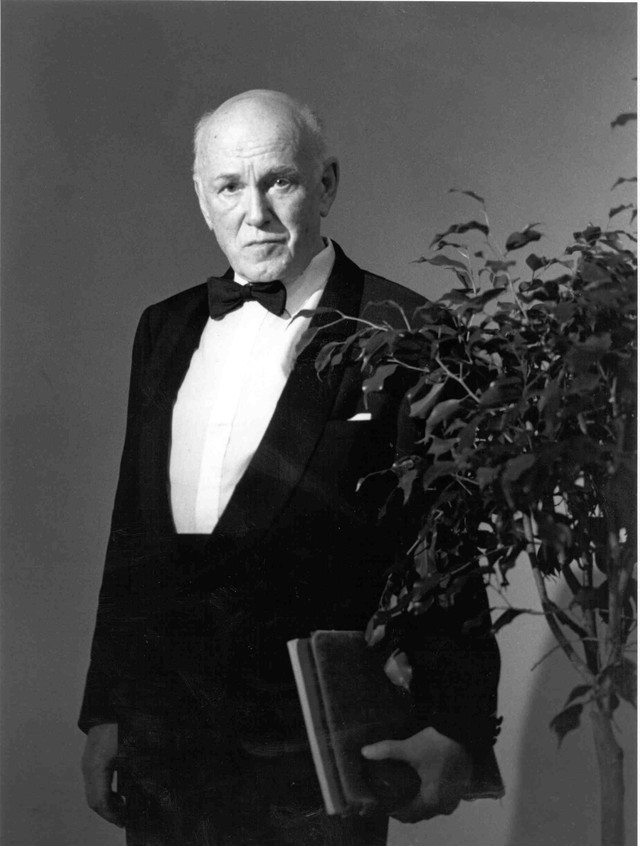

Our pianists are: Sviatoslav Richter, born on March 20th of 1915 in Zhytomyr, then in the Russian Empire, now a city in independent Ukraine. Richter is acknowledged by many as one of the greatest pianists of the 20th century. His repertoire was enormous, he said that he could play eighty different programs, not counting chamber pieces. He continued adding to it even in his 70s.

pieces. He continued adding to it even in his 70s.

Egon Petri, a German pianist of Dutch descent, was born on March 23rd of 1881 in Hanover. He was the favorite pupil and associate of Ferruccio Busoni. Petri had an illustrious international career and in 1923 became the first foreign pianist to perform in the Soviet Union. Like his teacher, much of Petri’s repertoire was concentrated on Bach, and like him, he became a famous pedagogue.

The American pianist Byron Janis will turn 95 on March 24th. He was born in McKeesport, PA into a Jewish family (the original family name was Yankelevitch). As a child, he studied with Josef and Rosina Lhévinne in New York. Vladimir Horowitz was in the audience when Janis, age 16, played Rachmaninov’s 2nd Piano Concerto and immediately took him as his first pupil. In 1960 Janis had a tremendously successful tour of the Soviet Union, just two years after Van Cliburn’s win of the First Tchaikovsky competition. Janis’s career was cut short in 1973 when he developed arthritis in both hands.

Wilhelm Backhaus, one of the most interesting German pianists of the 20th century, was born on March 26th of 1884 in Leipzig. An early protégé of Arthur Nikisch, he studied for a year with Eugene d’Albert but was mostly self-taught. In 1900, Backhaus toured England, and four years later he became a professor of music in Manchester. In 1912-1913 he toured the US, the first of his many highly successful tours of the country. In 1931 he became a Swiss citizen. His technique was legendary, and he maintained it well into his 80s. Backhaus was compromised by his association with the Nazis after their takeover in 1933. We’ll address this chapter of his life later.

So now to some Bach, as performed by our pianists. Here is an early (1948-1952) Sviatoslav Richter recording of Fantasia and Fugue in A minor, BWV 944. Bach wrote it sometime between 1707-1713/1714 when he was most likely in Weimar, where he was an organist and Konzertmeister at the ducal court.

And here is a much later work, Prelude, Fugue and Allegro in E-Flat Major, BWV 998, from 1740-1745, when Back was Thomaskantor in Leipzig. It’s performed by Egon Petri.

Here, 19-year-old Byron Janis plays Prelude and Fugue in A minor, BWV 543 as arranged by Liszt. The dating of this piece is all over the place: Grove Music says “after 1715,” Wikipedia – after 1730.

And finally, Wilhelm Backhaus plays the English Suite No. 6 in D minor, BWV 811 (here), composed sometime between 1720 and 1725. This is a bit problematic because in 1720 Bach was living in Köthen, serving as the Kapellmeister to the Prince of Anhalt-Köthen, while in 1725 he was already in Leipzig. Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: March 13, 2023. Telemann and Two Singers. Georg Philipp Telemann, the prolific friend of Johann Sebastian Bach, was born on March 14th of 1681. We’ve written about the “Telemann problem”: he was so abundant in his output as to make it practically impossible to account for all his compositions and to select – if not the best, then at least the most representative – pieces. Not just a wonderful composer, Telemann was also a very interesting person of apparently boundless energy: in addition to composing, he produced concerts, published music, taught, and wrote theoretical treaties. We’ll dedicate another entry to him, but this time we’ll just play some of his music – as it happens, an Orchestra suite La Bizarre (here). It’s performed by the Akademie Für Alte Musik Berlin.

written about the “Telemann problem”: he was so abundant in his output as to make it practically impossible to account for all his compositions and to select – if not the best, then at least the most representative – pieces. Not just a wonderful composer, Telemann was also a very interesting person of apparently boundless energy: in addition to composing, he produced concerts, published music, taught, and wrote theoretical treaties. We’ll dedicate another entry to him, but this time we’ll just play some of his music – as it happens, an Orchestra suite La Bizarre (here). It’s performed by the Akademie Für Alte Musik Berlin.

Two great singers were also born this week, both mezzo-sopranos and both born on the same day, March 16th: the German mezzo Christa Ludwig, and the Spanish Teresa Berganza, five years later, in 1933. Teresa Berganza died less than a year ago, on May 13th of 2022. We paid a tribute to her that year. Christa Ludwig died a year earlier, on April 24th of 2021 at the age of 93. She was born in Berlin, studied with her mother, and debuted at the age of 18 in Johann Strauss’s Die Fledermaus. In 1954 she sang the role of Cherubino in Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro at the Salzburg festival. In 1959 she made her American debut as Dorabella in Cosi fan Tutti at the Lyric opera in Chicago (Elisabeth Schwarzkopf was Fiordiligi). She would return to Chicago five more times,.jpg) singing Cherubino in Le nozze di Figaro, Fricka in Die Walküre, and roles in Boito’s Mefistofele, Verdi’s La forza del destino, and Richard Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier. She had a rich, very focused voice with no unnecessary vibrato. Her repertoire was large, from Monteverdi to Gluck, Mozart, Wagner, Verdi, and Berg. She was also a great lied singer and a wonderful Mahlerian, performing in his song cycles, such as Kindertotenlieder and Rückert-Lieder, and in Das Lied von der Erde and Symphony no. 3. She worked with the best conductors of her time, from Böhm and Klemperer to Bernstein, Solti, and Karajan.

singing Cherubino in Le nozze di Figaro, Fricka in Die Walküre, and roles in Boito’s Mefistofele, Verdi’s La forza del destino, and Richard Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier. She had a rich, very focused voice with no unnecessary vibrato. Her repertoire was large, from Monteverdi to Gluck, Mozart, Wagner, Verdi, and Berg. She was also a great lied singer and a wonderful Mahlerian, performing in his song cycles, such as Kindertotenlieder and Rückert-Lieder, and in Das Lied von der Erde and Symphony no. 3. She worked with the best conductors of her time, from Böhm and Klemperer to Bernstein, Solti, and Karajan.

Here is her Dorabella in the aria È amore un ladroncello from Mozart’s Così fan tutte. Karl Böhm conducts the Philharmonia Orchestra in this 1962 recording. And here Christa Ludwig is in an exceptional recording of Gustav Mahler’s Rückert-Lieder. Herbert von Karajan conducts the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: March 6, 2023. Honegger. The always popular Maurice Ravel was born this week, on March 7th of 1875. And so were Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, probably the most important composer among Johann Sebastian’s sons (on March 8th of 1714); Carlo Gesualdo, the brooding murderer and composer of huge talent (on the same day in 1566); Josef Mysliveček, a Czech friend of Mozart’s (on March 9th of 1737); and Samuel Barber, one of the most popular American composers of the 20th century (on March 9th of 1910). All of them we’ve written about on many occasions. One composer whom we’ve mentioned often but, quite undeservedly, only in passing, is Arthur Honegger, a Swiss and unusual member of Les Six.

the most important composer among Johann Sebastian’s sons (on March 8th of 1714); Carlo Gesualdo, the brooding murderer and composer of huge talent (on the same day in 1566); Josef Mysliveček, a Czech friend of Mozart’s (on March 9th of 1737); and Samuel Barber, one of the most popular American composers of the 20th century (on March 9th of 1910). All of them we’ve written about on many occasions. One composer whom we’ve mentioned often but, quite undeservedly, only in passing, is Arthur Honegger, a Swiss and unusual member of Les Six.

Honegger was born on March 10th of 1892 in the French port city of Le Havre to Swiss parents (there was an old Swiss colony in the city). As a child, Honegger studied the violin and harmony in Le Havre and then, for two years, in Zurich. At the age of 18, while still living in Zurich, he enrolled in the Paris Conservatory; he commuted there by train twice weekly. In Paris Honegger studied with Charles-Marie Widor, the famous organist and composer, and Vincent d'Indy. In 1913 Honegger settled in Montmartre, where he lived for the rest of his life. While at the Conservatory, he met Germaine Tailleferre, Georges Auric, Darius Milhaud, all future members of Les Six (Milhaud became his closest friend), and Jacques Ibert, with whom he would later collaborate on two pieces. In 1926 Honegger married a fellow pianist Andrée Vaurabourg. Their married life was unusual: Honegger required solitude to compose, so Andrée resided with her mother, while Honegger visited her every day for lunch. They lived apart for the rest of their married life, except for a period following Vaurabourg’s car accident, when Honegger took care of her, and at the end of Honegger’s life. Despite this arrangement, they had a daughter who was born in 1932. Vaurabourg was Honegger’s most trusted musical advisor; an excellent pianist, she was also a prominent teacher: among her students was Pierre Boulez.

During WWII Honegger remained in Paris and taught at the Ecole Normale de Musique. Depressed during the war, he further suffered from heart problems (a heart attack in 1947 almost killed him). He was in poor health for the rest of his life and died in November of 1955, the first of the Les Six. And speaking of Les Six, it was never a unified group, and esthetically, a serious-minded Honegger, mostly interested in large-form compositions like operas and musical dramas, was an odd man out. What kept them all together was stimulating companionship and appreciation of each other’s talent.

A composition that brought Honegger international fame was a 27-movement incidental score to a biblical drama Le roi David. Among his most popular pieces is Pacific 231, inspired by the sounds of a steam locomotive (Honegger was a big train enthusiast, he also loved fast cars and rugby). Here’s his last symphony, no. 5, subtitled “Di tre re” (or Of the three Ds, “re” is note D in the French notation. This note is played at the end of each movement). The Danish National Radio Symphony Orchestra is conducted by Neeme Järvi.Permalink

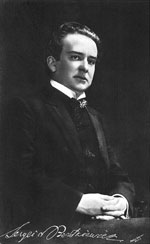

This Week in Classical Music: February 27, 2023. A mystery composer. Whom do you write about when you have Frédéric Chopin, Antonio Vivaldi, Gioachino Rossini, Bedřich Smetana, and Kurt Weill among the composers born this week, plus the pianist Issay Dobrowen, the violinist Gidon Kremer, the soprano Mirella Freni, and the conductor Bernard Haitink? The obvious answer is, you write about Sergei Bortkiewicz. Yes, we’re being facetious, but we’ve written about Chopin, Vivaldi, and Rossini many times (we haven’t had a chance to write about Dobrowen yet, a very interesting figure). Bortkiewicz, on the other hand, is a composer we knew only by name until recently when we heard his Symphony no. 1 and thought it was something from the late 19th century, maybe a very early Rachmaninov – but no, it turned out to be a piece composed in 1940. While conservatism is not the most admirable feature, Bortkiewicz is not alone in that regard: the above-mentioned Rachmaninov was also not the most adventuresome composer. Neither was Rimsky-Korsakov, not even Tchaikovsky, which didn’t preclude both of them from writing very interesting (and popular) music. Richard Strauss, for all his talent, was a follower of the Romantic tradition. Even Johann Sebastian Bach in his later years was well behind the prevailing trends of his time. Listen, for example, to two pieces written at about the same time: 1741-1742, Johann Sebastian’s wonderful, if somewhat archaic, Cantata Bekennen will ich seinen Namen BWV 200 (here), and then C.P.E.’s Symphony in G major, Wq. 173, written in the then “modern” style (here). They belong to different eras, even if the cantata is much better. We admire and love the pioneers like Mahler, Schoenberg, and Stravinsky, but as important as they are, there is a lot of space in the musical universe for the less daring composers. We’re not comparing the talent of Sergei Bortkiewicz with that of the “conservatives” mentioned above, but some of his music is pleasant and his life story is interesting.

and Kurt Weill among the composers born this week, plus the pianist Issay Dobrowen, the violinist Gidon Kremer, the soprano Mirella Freni, and the conductor Bernard Haitink? The obvious answer is, you write about Sergei Bortkiewicz. Yes, we’re being facetious, but we’ve written about Chopin, Vivaldi, and Rossini many times (we haven’t had a chance to write about Dobrowen yet, a very interesting figure). Bortkiewicz, on the other hand, is a composer we knew only by name until recently when we heard his Symphony no. 1 and thought it was something from the late 19th century, maybe a very early Rachmaninov – but no, it turned out to be a piece composed in 1940. While conservatism is not the most admirable feature, Bortkiewicz is not alone in that regard: the above-mentioned Rachmaninov was also not the most adventuresome composer. Neither was Rimsky-Korsakov, not even Tchaikovsky, which didn’t preclude both of them from writing very interesting (and popular) music. Richard Strauss, for all his talent, was a follower of the Romantic tradition. Even Johann Sebastian Bach in his later years was well behind the prevailing trends of his time. Listen, for example, to two pieces written at about the same time: 1741-1742, Johann Sebastian’s wonderful, if somewhat archaic, Cantata Bekennen will ich seinen Namen BWV 200 (here), and then C.P.E.’s Symphony in G major, Wq. 173, written in the then “modern” style (here). They belong to different eras, even if the cantata is much better. We admire and love the pioneers like Mahler, Schoenberg, and Stravinsky, but as important as they are, there is a lot of space in the musical universe for the less daring composers. We’re not comparing the talent of Sergei Bortkiewicz with that of the “conservatives” mentioned above, but some of his music is pleasant and his life story is interesting.

Sergei Bortkiewicz was born in Kharkiv on February 28th of 1877. Back then Kharkiv was part of the Russian Empire; now it is a city in Ukraine being constantly attacked by Putin’s Russian army. He studied music first in his hometown, then in St.-Petersburg, where one of his teachers was Anatoly Lyadov. In 1900 he entered the Leipzig Conservatory, where he studied piano and composition for two years. From 1904 to 1914 he lived in Berlin. While there he wrote a very successful Piano Concerto no. 1. At the outbreak of WWI, he, as a Russian citizen and therefore an enemy, was deported from Germany. Bortkiewicz settled temporarily in St.-Petersburg and then moved back to Kharkiv. After the October Revolution, amid the chaos of the Civil War, he emigrated to Constantinople and then, in 1922, to Vienna, where he lived for the rest of his life (he died there in 1952). In 1930 he wrote his Piano Concerto no. 2 for the left hand; it was one of the pieces commissioned by Paul Wittgenstein, the pianist who lost his right hand during the Great War. Altogether Bortkiewicz composed three piano concertos, two symphonies, an opera and several other symphonic and chamber pieces, all in the late-Romantic Russian style. It was as if the music of the 20th century hadn’t existed.

Here's Bortkiewicz Piano Concerto no. 1. It’s performed by Ukrainian musicians: Olga Shadrina is at the piano; Mykola Sukach is conducting the Odessa Philharmonic Orchestra. Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: February 20, 2023. Caruso. To our surprise, we realized that we’ve never written about Enrico Caruso, probably the greatest tenor of all time. (Come to think of it, we’ve never written about Beniamino Gigli either – we’ll certainly have to do it on his birthday, which comes in a month). Caruso was born in Naples on February 25th of 1873, so we’re celebrating not just any anniversary, but his 150th!

of it, we’ve never written about Beniamino Gigli either – we’ll certainly have to do it on his birthday, which comes in a month). Caruso was born in Naples on February 25th of 1873, so we’re celebrating not just any anniversary, but his 150th!

Caruso’s family was poor and had little formal education. As a boy, he had a nice but small voice, and one of his vocal teachers, upon first hearing him, pronounced that his voice was "too small and sounded like the wind whistling through the windows." Because he had little formal vocal training, his career had a bumpy start. Caruso had strained high notes and sounded more like a baritone than a tenor. His appearance at La Scala during the 1900–01 season in La bohème with Arturo Toscanini was not a success. Knowing how brilliant Caruso’s upper register was once he had fully developed his voice, it’s difficult to imagine his early struggles.

Caruso sang at several premieres: in 1897 in Milan, the title role in Francesco Cilea’s L'arlesiana, and in 1902 at the premiere of Adriana Lecouvreur, also by Cilea. It seems that somewhere around 1902 Caruso gained full control of his voice and from that point on went from one triumph to another, singing in Italy, then at the Convent Garden, and later at the Met. What used to be problematic had by then turned into an advantage: to quote Grove Music Dictionary, “the exceptional appeal of his voice was, in fact, based on the fusion of a baritone’s full, burnished timbre with a tenor’s smooth, silken finish, by turns brilliant and affecting.”

The Met became Caruso’s main stage: he sang 850 performances there and created 38 roles, some legendary, such as Canio in Leoncavallo’s I Pagliacci, Rodolfo in Puccini’s La bohème and Cavaradossi in Tosca, and Radames in Verdi’s Aida. A unique aspect of Caruso’s career was his relationship with the nascent recording industry. In 1903 he signed a contract with the Victor Talking Machine Company and later with the related Gramophone Company. During his time, all recordings were made acoustically, with the tenor singing into a metal horn (the electric recording was invented around 1925, after Caruso’s death). The records contained just 4 ½ minutes of music, which limited the repertoire Caruso could record (often music was edited to fit a record). And of course, these were not high-fidelity records, they distorted the timber of Caruso’s voice and lost some overtones. Still, they proved to be tremendously popular, helping both the industry and the singer. It was said that Caruso made the gramophone, and it made him.

During his career, Caruso partnered with the best singers of his generation, such as Nellie Melba, Amelita Galli-Curci, and Luisa Tetrazzini. He toured, triumphantly, across Europe and South America. Unfortunately, his career was short. In September of 1920, he fell ill with an undetermined internal pain; eventually got better but the December 11th performance of L'elisir d'amore had to be canceled after the first act, as Caruso suffered throat bleeding. It was later determined that he had pleurisy. His lungs were drained, and he started recuperating. Caruso returned to Naples in May of 1921, which probably was a mistake: his care there was inadequate, and he died on August 2nd of 1921.

With all the deficiencies of the old recording, we still can enjoy Caruso’s magnificent voice. Here are several of them. Se quel guerrier io fossi! Celeste Aida, from Act 1 of Verdi’s Aida; Una furtiva lagrima, from Act 2 of Donizetti’s L'elisir d'amore; La donna è mobile from Act 3 of Verdi’s Rigoletto; Ella mi fu Rapita...parmi veder le lagrime, from Act 2 of the same opera; Addio alla madre, from Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana; and Vesti la giubba from Act 1 of I Pagliacci by Leoncavallo.Permalink