Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

This Week in Classical Music: May 23, 2022. Four Composers and Teresa Stratas. Jean Françaix, William Bolcom, Isaac Albéniz and Erich Wolfgang Korngold were all born this week – a Frenchman, an American, a Spaniard and an Austrian who emigrated to the US. There is a similarity between Françaix (born on May 23rd of 1912) and Bolcom (b. 5/26/1938), not necessarily in the style of their music but rather in the wonderful sense of humor and lightness (it may not be quite a coincidence, as Bolcom had studied with two French composer, Darius Milhaud at Mills College in California and with Milhaud and Olivier Messiaen at the Paris Conservatory). Here’s Françaix’s Trio for Oboe, Bassoon, and Piano and here – one of Bolcom’s Twelve New Etudes, Hymne a l'amour. The Trio is played by Julien Hardy (Bassoon), Frédéric Tardy (Oboe), Simon Zauoi (Piano). The pianist in the Bolcom is Marc-André Hamelin.

week – a Frenchman, an American, a Spaniard and an Austrian who emigrated to the US. There is a similarity between Françaix (born on May 23rd of 1912) and Bolcom (b. 5/26/1938), not necessarily in the style of their music but rather in the wonderful sense of humor and lightness (it may not be quite a coincidence, as Bolcom had studied with two French composer, Darius Milhaud at Mills College in California and with Milhaud and Olivier Messiaen at the Paris Conservatory). Here’s Françaix’s Trio for Oboe, Bassoon, and Piano and here – one of Bolcom’s Twelve New Etudes, Hymne a l'amour. The Trio is played by Julien Hardy (Bassoon), Frédéric Tardy (Oboe), Simon Zauoi (Piano). The pianist in the Bolcom is Marc-André Hamelin.

The biography of Erich Wolfgang Korngold is very unusual. Born on May 29th of 1897 in Vienna, he was a child prodigy, composing a piano sonata at the age of 11 (it was published and performed), a ballet Der Schneemann that same year and a large-form orchestral piece he called Sinfonietta (it runs for about 42 minutes) when he was 15. Korngold was Jewish and emigrated to the US in 1934, where he became one of the most influential movie composers of the time. We would have thought that Korngold had to change his compositional style to accommodate films, but this is not quite true: listen, for example, to the first movement of Sinfonietta and you’ll hear the echoes of the Korngold of The Adventures of Robin Hood.

Teresa Stratas, the wonderful Canadian soprano of Greek descent, was born on May 26th of 1938 in Toronto. Stratas was famous for many contemporary roles, singing in the operas of Gian Carlo Menotti, Francis Poulenc, Kurt Weill, John Corigliano, and especially, the role of Lulu in the Berg eponymous opera’s first complete performance and recording (in 1979, with Pierre Boulez conducting). But Stratas didn’t limit herself to the 20th century repertoire, her range was actually very broad. She was wonderful as Zerlina in Don Giovanni, Despina in Così fan tutte, and sung two roles, Cherubino and Susanna in The Marriage of Figaro by Mozart. She performed in several Puccini’s operas, in Tchaikovsky’s Queen of Spades, Strauss operas and also Verdi’s. Here, from 1968, is her wonderful Susanna in the aria Deh vieni, non tarda, from Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro. This is a live recording with Zubin Mehta conducting the RAI Orchestra.Permalink

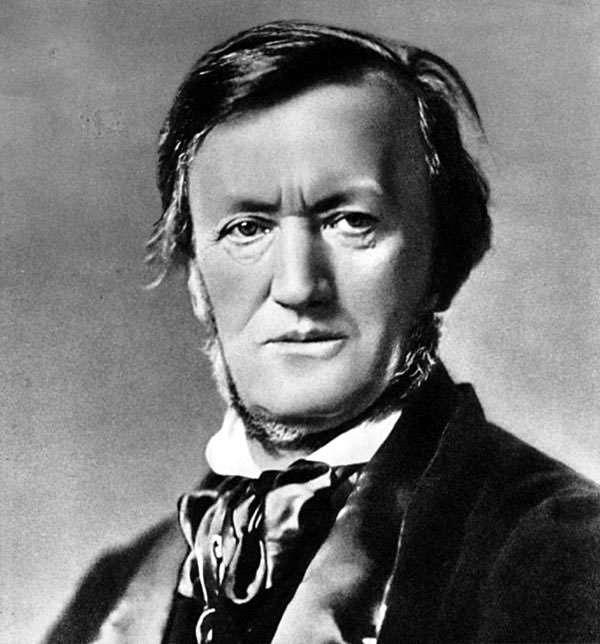

This Week in Classical Music: May 16, 2022. Wagner, Berganza and Nilssen. Richard Wagner was born this week, on May 22nd of 1813, but we’d like to start with the passing of the wonderful Spanish mezzo-soprano Teresa Berganza three days ago at the age of 89. Berganza was born in Madrid on March 16th of 1933. She made her operatic debut as Dorabella (it would become one of her signature roles) in Mozart's Così fan tutte in 1957 at the Aix-en-Provence and that same year made a La Scala debut. Early in her career her voice was lighter, perfectly suited for Rossini’s bel canto operas: her Cenetrentola was unsurpassed. Rosina in Rossini's Il barbiere di Siviglia was another famous role of hers. Later in her career her voice darkened and Berganza took on the role

wonderful Spanish mezzo-soprano Teresa Berganza three days ago at the age of 89. Berganza was born in Madrid on March 16th of 1933. She made her operatic debut as Dorabella (it would become one of her signature roles) in Mozart's Così fan tutte in 1957 at the Aix-en-Provence and that same year made a La Scala debut. Early in her career her voice was lighter, perfectly suited for Rossini’s bel canto operas: her Cenetrentola was unsurpassed. Rosina in Rossini's Il barbiere di Siviglia was another famous role of hers. Later in her career her voice darkened and Berganza took on the role of Carmen, in which she also excelled. Berganza sang at all major opera houses around the world and was one of the most beloved singers of the second half of the 20th century. Here’s the final scene (about 6 minutes) from La Cenerentola in the live 1967 recording from Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires. We had to cut the unending ovation; the agility of Berganza’s voice in this recording is remarkable.

of Carmen, in which she also excelled. Berganza sang at all major opera houses around the world and was one of the most beloved singers of the second half of the 20th century. Here’s the final scene (about 6 minutes) from La Cenerentola in the live 1967 recording from Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires. We had to cut the unending ovation; the agility of Berganza’s voice in this recording is remarkable.

Berganza never sung in Wagner’s operas – her voice was not suited for his roles, even though Wagner wrote several of them for mezzo, for example, Waltraute, a Valkyrie and Brünnhilde’s sister in Götterdämmerung, or the goddess Frika, Wotan’s wife in Die Walküre. On the other hand, the great Swedish Birgit Nilsson was one of the best interpreters of Wagner roles in the 20th century. Nilsson was born in a tiny village of Västra Karup on May 17th of 1918. Her operatic career started in Stockholm in 1946; early in her career she sung many roles in the Italian repertoire (Aida, Tosca), operas of Mozart, Richard Strauss and Tchaikovsky. She first appeared in a Wagner role in the Stockholm Opera’s 1954-55 season and then sung Brünnhilde in the complete Ring cycle. In 1957 she performed at Bayreuth for the first time; that was the beginning of a long association with the festival which lasted till 1970. In 1959 she made her Metropolitan debut as Isolde and went on to sing in 200 performances and 16 roles. Let us quote from Grove Music: “Nilsson was generally considered the finest Wagnerian soprano of her day. Her voice was even throughout its range, pure in sound and perfect in intonation with a free ringing top; its size was phenomenal.”

beginning of a long association with the festival which lasted till 1970. In 1959 she made her Metropolitan debut as Isolde and went on to sing in 200 performances and 16 roles. Let us quote from Grove Music: “Nilsson was generally considered the finest Wagnerian soprano of her day. Her voice was even throughout its range, pure in sound and perfect in intonation with a free ringing top; its size was phenomenal.”

Here’s the incredible Immolation Scene, from 1965 and remastered in 2012. Birgit Nilsson is Brünnhilde, Wiener Philharmoniker is conducted by Georg Solti. You can hear that the quote from Grove is not an exaggeration but a literal description of every aspect of Nisson’s voice. We also think that in this recording both the orchestra playing and conducting are excellent.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: May 9, 2022. Monteverdi. Claudio Monteverdi was born 455 years ago; he was baptized in Cremona on May 15th of 1567. Monteverdi is one of the most important composers in the history of European music: a “father of the opera,” his music also spanned two different eras, the late Renaiss ance and early Baroque; he created masterpieces in both styles. We’ve written about him on many occasions (for example, here and here), so today we’ll present two madrigals from Monteverdi’s very first Book of Madrigals, which were composed in 1582-3, while Monteverdi was still a teenager, and published in Venice in 1584. Here are his Ch’ami la vita mia nel tuo bel nome (Madrigal 1) and A che tormi il ben mio (Madrigal 3), performed by the ensemble Le Nuove Musiche under the direction of Koetsveld Krijn. Not bad for a 15-year-old, wouldn’t you say?

ance and early Baroque; he created masterpieces in both styles. We’ve written about him on many occasions (for example, here and here), so today we’ll present two madrigals from Monteverdi’s very first Book of Madrigals, which were composed in 1582-3, while Monteverdi was still a teenager, and published in Venice in 1584. Here are his Ch’ami la vita mia nel tuo bel nome (Madrigal 1) and A che tormi il ben mio (Madrigal 3), performed by the ensemble Le Nuove Musiche under the direction of Koetsveld Krijn. Not bad for a 15-year-old, wouldn’t you say?

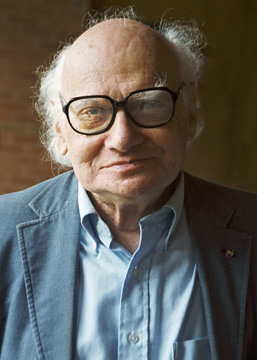

We’ve mentioned Milton Babbitt’s name several times in the past but have never written about him directly and never presented his music. The reason is that Babbitt’s music is rather difficult, even when the harmonies are translucent, as there’s no tonal base to much of his music: it’s written in a 12-tone, serial style. Babbitt was born into a Jewish family on May 10th of 1916 in Philadelphia and brought up in Jackson, Mississippi. His first instrument was the violin, later he studied the clarinet and saxophone. At the age of 15 he entered the University of Pennsylvania intending to become a mathematician but soon transferred to New York University to study music. In New York, Babbitt got interested in philosophy and the music of modern composers, the Americans Varèse and Stravinsky and then composers of the Second Viennese school. After graduating from NYU Babbitt studied with Roger Sessions and then enrolled in the post-graduate studies in Princeton, where he not only studied music but became a member of the Department of Mathematics. Mathematics came in handy when Babbitt decided to write a PhD thesis in musicology, analyzing Schoenberg’s compositional methods (the name of the paper, The Function of Set Structure in the Twelve-Tone System, was as technical as its substance). Nobody at Princeton’s music department could understand it and the thesis was rejected. It was resubmitted on Babbitt’s behalf twenty years later and accepted. The Dean of the Graduate School of Music explained that Babbitt’s “dissertation was so far ahead of its time it couldn’t be properly evaluated...” There were other controversies in Babbitt’s life: in 1958 he wrote an article suggesting that serious music requires an educated audience. The magazine, High Fidelity, published it under the provocative title “Who Cares if You Listen,” given to it by the editor, not Babbitt, which was not at all what the composer had in mind. As he said later, “I care very deeply if you listen. From a purely practical point of view, if nobody listens and nobody cares, you’re not going to be writing music for very long. But I care how you listen.”

In New York, Babbitt got interested in philosophy and the music of modern composers, the Americans Varèse and Stravinsky and then composers of the Second Viennese school. After graduating from NYU Babbitt studied with Roger Sessions and then enrolled in the post-graduate studies in Princeton, where he not only studied music but became a member of the Department of Mathematics. Mathematics came in handy when Babbitt decided to write a PhD thesis in musicology, analyzing Schoenberg’s compositional methods (the name of the paper, The Function of Set Structure in the Twelve-Tone System, was as technical as its substance). Nobody at Princeton’s music department could understand it and the thesis was rejected. It was resubmitted on Babbitt’s behalf twenty years later and accepted. The Dean of the Graduate School of Music explained that Babbitt’s “dissertation was so far ahead of its time it couldn’t be properly evaluated...” There were other controversies in Babbitt’s life: in 1958 he wrote an article suggesting that serious music requires an educated audience. The magazine, High Fidelity, published it under the provocative title “Who Cares if You Listen,” given to it by the editor, not Babbitt, which was not at all what the composer had in mind. As he said later, “I care very deeply if you listen. From a purely practical point of view, if nobody listens and nobody cares, you’re not going to be writing music for very long. But I care how you listen.”

Here are Three Compositions for the piano, composed in 1947-48. It’s the earliest mature piano pieces by Babbitt. They are performed by the American pianist Robert Taub and, according to the notes, were recorded at the Church of The Holy Trinity, New York, April of 1985 in the presence of the composer.Permalink

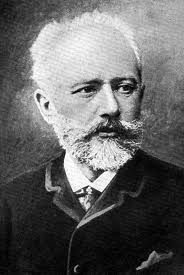

This Week in Classical Music: May 2, 2022. Tchaikovsky (and War in Ukraine). Pyotr Tchaikovskywas born on May 7th of 1840. He’s acknowledged as the greatest Russian composer of all time (or, realistically, of the last two centuries that classical music has existed in Russia in its present form), but on March 9th of 2022 the Cardiff Philharmonic Orchestra cancelled its all-Tchaikovsky concert as “inappropriate at this time” (due to war in Ukraine) and replaced it with the music of Dvořák, John Williams, and Elgar. Many things come to mind. To make it absolutely clear, we’d like to state (again) that we believe the Russian aggression against Ukraine to be criminal and inhumane and hope that Russian President Putin will end up in the Hague. But to cancel a Tchaikovsky concert? First of all, the idea of “canceling” is clearly of our time, when people and speech are routinely cancelled by our media, networks and social institutions. Secondly, what does Tchaikovsky has to do with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine? Was he anti-Ukrainian, as Wagner was anti-Semitic? No. Was he xenophobic, an ardent Russian nationalist? Absolutely not. Just the opposite, Tchaikovsky was one of the most progressive, Westernized composers of his era. He traveled broadly, spending years in Italy and other countries, premiered his music in Europe, conducted the New York Music Society's orchestra. He was also gay, an anathema in modern-day’s Russia. Why would anybody associate him with the evil of Mr. Putin’s Russia? One can like Tchaikovsky’s music more or, as the late NY Time music critic Harold Schonberg, you could like it less, but to cancel him is absurd. Interestingly, the offending piece in the original program, according to the Cardiff Phil, was the “nationalistic” 1812 Overture. This is absurd on many levels: this music was “culturally appropriated” in the United States as practically the official anthem of the 4th of July, and it was written to celebrate the victory against the aggressor, not an aggression!

of all time (or, realistically, of the last two centuries that classical music has existed in Russia in its present form), but on March 9th of 2022 the Cardiff Philharmonic Orchestra cancelled its all-Tchaikovsky concert as “inappropriate at this time” (due to war in Ukraine) and replaced it with the music of Dvořák, John Williams, and Elgar. Many things come to mind. To make it absolutely clear, we’d like to state (again) that we believe the Russian aggression against Ukraine to be criminal and inhumane and hope that Russian President Putin will end up in the Hague. But to cancel a Tchaikovsky concert? First of all, the idea of “canceling” is clearly of our time, when people and speech are routinely cancelled by our media, networks and social institutions. Secondly, what does Tchaikovsky has to do with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine? Was he anti-Ukrainian, as Wagner was anti-Semitic? No. Was he xenophobic, an ardent Russian nationalist? Absolutely not. Just the opposite, Tchaikovsky was one of the most progressive, Westernized composers of his era. He traveled broadly, spending years in Italy and other countries, premiered his music in Europe, conducted the New York Music Society's orchestra. He was also gay, an anathema in modern-day’s Russia. Why would anybody associate him with the evil of Mr. Putin’s Russia? One can like Tchaikovsky’s music more or, as the late NY Time music critic Harold Schonberg, you could like it less, but to cancel him is absurd. Interestingly, the offending piece in the original program, according to the Cardiff Phil, was the “nationalistic” 1812 Overture. This is absurd on many levels: this music was “culturally appropriated” in the United States as practically the official anthem of the 4th of July, and it was written to celebrate the victory against the aggressor, not an aggression!

What adds insult to injury is the replacement of Tchaikovsky’s music with that of John Williams, his Cowboy Overture in particular. For those who are unfamiliar with this “masterpiece,” we recommend sampling it on YouTube (we’d rather not reproduce it here). It’s movie-music at its most mediocre. Not all of Tchaikovsky’s music is great, he really wrote some crummy pieces, but any one of them is on a different, and much higher, plane than this.

To celebrate Tchaikovsky’s birthday, here’s his Violin Concertо, performed by the German violinist Julia Fischer, accompanied by the Russian National Orchestra under the direction of Russian-Jewish-American conductor Yakov Kreizberg. A side note: the Russian National Orchestra was created by the pianist and conductor Mikhail Pletnev in 1990. Less than a month ago, Svetlana Rips, the director of the orchestra was fired by the Russian Ministry of Culture and replaced by a Putin loyalist. It’s rumored that Pletnev may lose his position as well.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: April 25, 2022. Catching up (and War in Ukraine). The previous two weeks we’ve ignored many anniversaries while talking about two Italians, the conductor Victor de Sabata and the amazing Renaissance composer and theoretician Nicola Vicentino. We missed the birthday of.jpg) the great Russian-Soviet composer Sergei Prokofiev, who was born on April 23rd of 1891 in a small village of Sontsivka. Sontsivka is located in the Donetsk oblast’, Ukraine – yes, the Russian Prokofiev was born in Ukraine, which then, like many other countries, was part of the Russian Empire. And this is where the war is raging today: the village is about 10 miles from the front line. Russia invaded Ukraine, unprovoked, on February 24th of this year and is waging a barbaric war against its neighbor, killing thousands of civilians, and committing unspeakable crimes. There is a Prokofiev Museum in Sontsivka, and if the Russian force advance, there is a good chance it will be gone, as Russian forces annihilate everything on their path. Yesterday the people of Russia and Ukraine celebrated the Orthodox Easter. We don’t know how the Russians could stand to go to their churches, as their spiritual leader, Patriarch Kirill, fully supports Putin’s war, has prayed for the Russian Arm Forces, and called them “heroes” while these “heroes” are using artillery against Ukrainian churches and the civilians who hide there.

the great Russian-Soviet composer Sergei Prokofiev, who was born on April 23rd of 1891 in a small village of Sontsivka. Sontsivka is located in the Donetsk oblast’, Ukraine – yes, the Russian Prokofiev was born in Ukraine, which then, like many other countries, was part of the Russian Empire. And this is where the war is raging today: the village is about 10 miles from the front line. Russia invaded Ukraine, unprovoked, on February 24th of this year and is waging a barbaric war against its neighbor, killing thousands of civilians, and committing unspeakable crimes. There is a Prokofiev Museum in Sontsivka, and if the Russian force advance, there is a good chance it will be gone, as Russian forces annihilate everything on their path. Yesterday the people of Russia and Ukraine celebrated the Orthodox Easter. We don’t know how the Russians could stand to go to their churches, as their spiritual leader, Patriarch Kirill, fully supports Putin’s war, has prayed for the Russian Arm Forces, and called them “heroes” while these “heroes” are using artillery against Ukrainian churches and the civilians who hide there.

Sarcasm may not be the most appropriate reaction to what is happening in Ukraine, but Prokofiev was generally a very optimistic person, and there is not much in his music that would relate to the horrors we are witnessing today; his short piano Sarcasms may be the closest in spirit. Daniil Trifonov plays the third movement, Allegro precipitato (here). If not, then maybe Suggestion diabolique (Prokofiev was 17 when he wrote it). The pianist is Andrei Gavrilov (here).

Another name we failed to mention last week: John Eliot Gardiner. This British conductor was born on April 20th of 1943. He’s one of the most renowned interpreters of the music of Bach; his Bach Cantata Pilgrimage was a tremendous undertaking: he performed all Bach’s sacred cantatas (there are 198 extant) during a one-year period, traveling from one city to another in Europe and America. Good Friday was just 10 days ago. Here are the last 12 minutes of Bach’s St. John Passion, which was first performed on Good Friday of 1724 in the St. Nicholas Church in Leipzig. We’ll start with the Chorale O hilf, Christe, Gottes Sohn (Oh help us, Christ, God’s Son). The Evangelist’s Recitative Then Joseph of Arimathia follows, and then the final Chorus Ruht wohl, ihr heiligen Gebeine, (Rest in peace, your sacred limbs) and Chorale Ach Herr, lass dein lieb Engelein (Ah Lord, let your dear angels). TheEnglish Baroque Soloists and Monteverdi Choir are led by Sir John Eliot Gardiner.Permalink

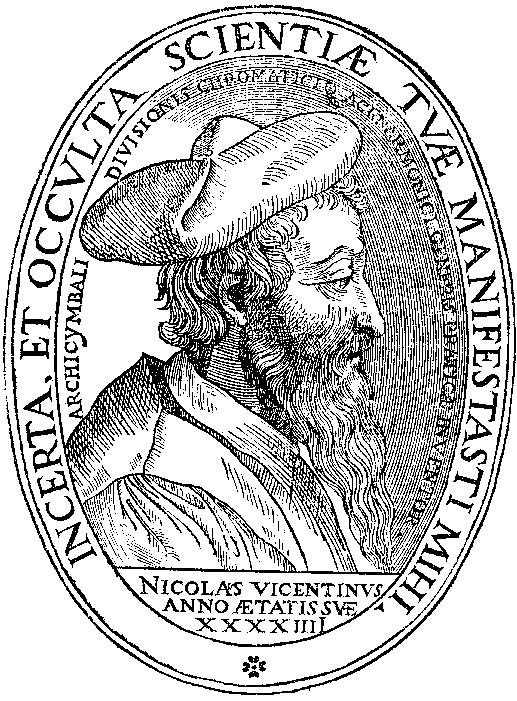

This Week in Classical Music: April 18, 2022. Microtonal Renaissance: Nicola Vicentino. Sometime ago we presented an entry about Easley Blackwood, an American composer who wrote microtonal music, music for electronic instruments tuned to more than 12 half-tones to an octave – 13, for example, or 14. Blackwood actually tried 12 more tunings, dividing the octave up to 24 equal intervals. The results were interesting and the attempt pretty courageous, as not that many composers have tried to work in this field. Well, it turns out that Blackwood had a predecessor. Four centuries earlier there lived an audacious composer who also attempted to go beyond the usual 12 half-tone octave we are so used to hearing. His name is Nicola Vicentino. Vicentino was born, as his name suggests, in the city of Vicenza in 1511. He probably studied with Adrian Willaert in nearby Venice. Sometime between 1530 and 1540 he went to Ferrara, Italy’s major musical center. Clearly, he made a career there, as he became the music tutor to the family of the Duke Ercole II and some of his music was performed at the court. In 1546 a book of his madrigals was published in Venice. Sometime later he followed Cardinal Ippolito II d’Este, the second son of Duke Alfonso I d'Este, Ercole’s brother, and the infamous Lucrezia Borgia, to Rome. There, in 1551, a famous debate took place between Vicentino and the Portuguese musician Vicente Lusitano. The debate centered on different interpretations of historical tuning systems with references to the ancient Greek music. It’s too esoteric for us to follow but the idea that such a musical debate could generate interest comparable to that of a Grammy pop-album winner of today is remarkable in itself. Vicentino lost the debate, which was formally judged by several professional musicians, but that didn’t stop him from writing an influential musical treatise and practically experimenting with his ideas. One thing he did was to invent a new musical instrument he called arcicembalo. It was based on a standard harpsichord with two manual keyboards. All black keys were divided in two and there were additional black keys between B and C and between E and F. The arcicembalo could be tuned differently; one way would divide the octave into 31 equal intervals. Vicentino wrote music for his new instrument, and for a similarly tuned arciorgano. He also wrote vocal music using quarter-tones (you can listen to some samples below). Following Ippolito II, Vicentino returned to Ferrara; in 1563 he left the service of the cardinal and assumed the post of maestro di cappella in his hometown at the Vicenza Cathedral. His later life isn’t clear: it seems that he spent some time in Milan, applied for a position in Bavaria but didn’t receive it and died during a plague in Milan in 1576. One of Vicentino’s arcicembalos with 31 notes to the octave is extant, it’s now on display in the Bologna International music museum.

microtonal music, music for electronic instruments tuned to more than 12 half-tones to an octave – 13, for example, or 14. Blackwood actually tried 12 more tunings, dividing the octave up to 24 equal intervals. The results were interesting and the attempt pretty courageous, as not that many composers have tried to work in this field. Well, it turns out that Blackwood had a predecessor. Four centuries earlier there lived an audacious composer who also attempted to go beyond the usual 12 half-tone octave we are so used to hearing. His name is Nicola Vicentino. Vicentino was born, as his name suggests, in the city of Vicenza in 1511. He probably studied with Adrian Willaert in nearby Venice. Sometime between 1530 and 1540 he went to Ferrara, Italy’s major musical center. Clearly, he made a career there, as he became the music tutor to the family of the Duke Ercole II and some of his music was performed at the court. In 1546 a book of his madrigals was published in Venice. Sometime later he followed Cardinal Ippolito II d’Este, the second son of Duke Alfonso I d'Este, Ercole’s brother, and the infamous Lucrezia Borgia, to Rome. There, in 1551, a famous debate took place between Vicentino and the Portuguese musician Vicente Lusitano. The debate centered on different interpretations of historical tuning systems with references to the ancient Greek music. It’s too esoteric for us to follow but the idea that such a musical debate could generate interest comparable to that of a Grammy pop-album winner of today is remarkable in itself. Vicentino lost the debate, which was formally judged by several professional musicians, but that didn’t stop him from writing an influential musical treatise and practically experimenting with his ideas. One thing he did was to invent a new musical instrument he called arcicembalo. It was based on a standard harpsichord with two manual keyboards. All black keys were divided in two and there were additional black keys between B and C and between E and F. The arcicembalo could be tuned differently; one way would divide the octave into 31 equal intervals. Vicentino wrote music for his new instrument, and for a similarly tuned arciorgano. He also wrote vocal music using quarter-tones (you can listen to some samples below). Following Ippolito II, Vicentino returned to Ferrara; in 1563 he left the service of the cardinal and assumed the post of maestro di cappella in his hometown at the Vicenza Cathedral. His later life isn’t clear: it seems that he spent some time in Milan, applied for a position in Bavaria but didn’t receive it and died during a plague in Milan in 1576. One of Vicentino’s arcicembalos with 31 notes to the octave is extant, it’s now on display in the Bologna International music museum.

Ensemble Exaudi is one of the few ensembles that attempts to interpret the music of Vicentino. It’s easier, at least in theory, to sing Vicentino’s quarter-tones and one-fifth-tones as you don’t have to have a very special keyboard instrument, but in practice you have to be a virtuoso performer with an excellent ear to follow composer’s directions. Here is Vicentino’s Musica prisca caput. Listen carefully! And here is his Madonna, il poco dolce, another remarkable piece. And finally, another madrigal, Dolce mio ben. It’s invigorating to find new music that is really interesting while so much mediocrity is being promoted by our musical establishment. We look forward to the (hopefully near) future when talented pieces take their deserved place, the place earned by the quality of compositions, not political expediency.Permalink