Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

This Week in Classical Music: August 29, 2022. Bruckner and three conductors. Sometimes we write about a composer and a musician born the same week and can illustrate the music of the former as interpreted by the latter. This week we have three famous conductors, all born on the same day, but it turns out that only one of them ever recorded a symphony by our composer of the week, Anton Bruckner. It’s not very surprising that one of our conductors never played the music of Bruckner: Tullio Serafin, who was born on September 1st of 1878, was one of the greatest opera conductors of the 20th century and had a limited symphonic career. On top of that, the music of Bruckner wasn’t popular in Italy till much later in the 20th century. Serafin, born not far from Venice, studied at the Milan Conservatory and made his conducting debut in Ferrara in 1898. He became the Principal Conductor at the La Scala in 1914. His main repertoire there came from the 19th century, but he also premiered operas by Richard Strauss, Rimsky-Korsakov, Dukas and several other contemporaries. From 1924 to 1934 he worked at the Metropolitan Opera where

former as interpreted by the latter. This week we have three famous conductors, all born on the same day, but it turns out that only one of them ever recorded a symphony by our composer of the week, Anton Bruckner. It’s not very surprising that one of our conductors never played the music of Bruckner: Tullio Serafin, who was born on September 1st of 1878, was one of the greatest opera conductors of the 20th century and had a limited symphonic career. On top of that, the music of Bruckner wasn’t popular in Italy till much later in the 20th century. Serafin, born not far from Venice, studied at the Milan Conservatory and made his conducting debut in Ferrara in 1898. He became the Principal Conductor at the La Scala in 1914. His main repertoire there came from the 19th century, but he also premiered operas by Richard Strauss, Rimsky-Korsakov, Dukas and several other contemporaries. From 1924 to 1934 he worked at the Metropolitan Opera where he staged several first American productions of what’s now considered the staples of the operatic repertoire, for example, Simon Boccanegra and Turandot. In 1934 he returned to Italy and was appointed the artistic director of Teatro Reale in Rome. He remained there for nine years. After WWII he conducted the first season of the reopened La Scala.

he staged several first American productions of what’s now considered the staples of the operatic repertoire, for example, Simon Boccanegra and Turandot. In 1934 he returned to Italy and was appointed the artistic director of Teatro Reale in Rome. He remained there for nine years. After WWII he conducted the first season of the reopened La Scala.

Serafin was famous for coaching several generations of singers, from Rosa Ponselle at the Met to Magda Olivero, whom he encouraged to sing in the bel canto repertoire, at La Scala. He also worked with the three greatest sopranos of the century - Joan Sutherland, while she was at the Covent Garden, Renata Tebaldi, and Maria Callas. With Callas he made several legendary recordings, such as the 1953 Tosca (which also featured Giuseppe Di Stefano and Tito Gobbi), the 1954 Norma, Lucia di Lammermoor, recorded in 1959, and other. Serafin continued conducting into his 80s. In 1962, when he was 84, he was appointed the Artistic adviser of the Rome opera. Serafin died in Rome on February 2nd of 1968 in his 90th year.

It is much more surprising that our second conductor has never recorded a Bruckner symphony: Leonard Slatkin, who was born in 1944, also on September 1st, lead many American and European orchestras in a broad selection of works. On the other hand, he has never recorded a single Beethoven’s symphony either (we’re talking about recordings, Slatkin often conducted Beethoven in concerts, he even led a series of Beethoven festivals with the San Francisco Symphony during the late 1970s and 80s). Slatkin was born in Los Angeles, studied at the Juilliard and other schools, and started conducting in 1966. In the 1980s he made the Saint Louis Symphony into a world class orchestra. For eight years he was the music director of the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington and led the BBC Symphony orchestra for four years. From 2008 to 2018 Slatkin was the Music director of the Detroit Symphony and did much to rebuild the orchestra in the aftermath of the disastrous strike. These days Slatkin continues an active guest-conducting career although at a slower pace.

Finally (and very briefly) the conductor who did record a Bruckner: Seiji Ozawa, born on September 1st of 1935. One of the most important conductors of the last 50 years, Ozawa was sometimes criticized, especially at the end of his tenure at the Boston Symphony Orchestra. We have a special feeling for Ozawa, as we heard him conduct the Boston Symphony in the most remarkable Mahler 3rd in 1998 in Vienna’s Musikverein. Here’s the first movement of Bruckner’s Symphony no. 7. Seiji Ozawa conducts the Saito Kinen Orchestra.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: August 22, 2022. Likas Foss and Ivry Gitlis. Last week we inadvertently missed an important anniversary: the 100th birthday of the German-American composer, pianist and conductor Lukas Foss, who was born in Berlin on August 15th of 1922 (he moved to Paris in 1933 and to the US in 1937). We wrote an entry about him two years ago, so today we’ll just play some of his music. Here’s a charming Lulu’s song, from Foss’s 1953 comic opera The Jumping Frog Of Calveras County. Judith Kellock is the soprano, the composer is on the piano. And here, from 1959-60, is the first part, We’re Late, of Foss’s Time Cycle for soprano and orchestra. Adele Addison is the soprano, Leonard Bernstein leads the Columbia Symphony Orchestra. (A note about Adele Addison: she was born in New York in 1925 and is still with us, at the age of 97. Addison was educated at Princeton and later continued her studies at the Juilliard. She sang several opera roles but was better known as a recitalist and concert singer, especially in the contemporary repertoire and Baroque music. She was at her peak in 1950s and 60s, when she often sung with the New York Philharmonic under the direction of Leonard Bernstein. She later taught at the Manhattan School of Music – Dawn Upshaw was one of her students. Though not especially relevant, but Adele Addison, like Leontyne Price, Shirley Verrett, Grace Bumbry, Jessye Norman, and Maria Ewing, is black.)

composer, pianist and conductor Lukas Foss, who was born in Berlin on August 15th of 1922 (he moved to Paris in 1933 and to the US in 1937). We wrote an entry about him two years ago, so today we’ll just play some of his music. Here’s a charming Lulu’s song, from Foss’s 1953 comic opera The Jumping Frog Of Calveras County. Judith Kellock is the soprano, the composer is on the piano. And here, from 1959-60, is the first part, We’re Late, of Foss’s Time Cycle for soprano and orchestra. Adele Addison is the soprano, Leonard Bernstein leads the Columbia Symphony Orchestra. (A note about Adele Addison: she was born in New York in 1925 and is still with us, at the age of 97. Addison was educated at Princeton and later continued her studies at the Juilliard. She sang several opera roles but was better known as a recitalist and concert singer, especially in the contemporary repertoire and Baroque music. She was at her peak in 1950s and 60s, when she often sung with the New York Philharmonic under the direction of Leonard Bernstein. She later taught at the Manhattan School of Music – Dawn Upshaw was one of her students. Though not especially relevant, but Adele Addison, like Leontyne Price, Shirley Verrett, Grace Bumbry, Jessye Norman, and Maria Ewing, is black.)

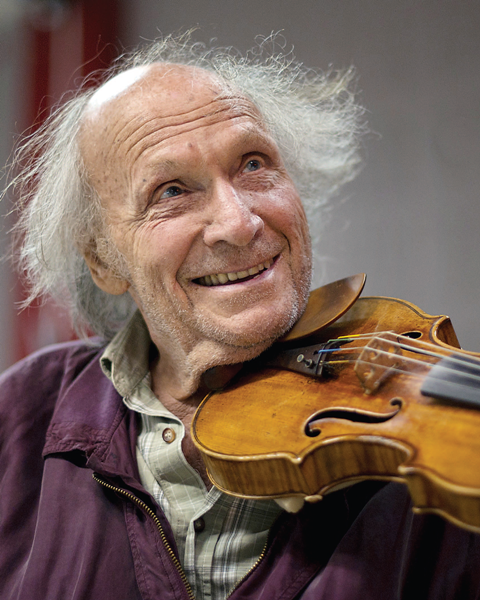

We also have another centenary: the Israeli violinist Ivry Gitlis was born on August 22nd of 1922 in Haifa. His parents had emigrated from Kamianets-Podilskyi in western Ukraine the previous year. Ivry took up the violin at the age of five, and at the age of eight played to Bronisław Huberman, the famous Polish violinist who was visiting Palestine (several years later, in 1936, Huberman founded Israel’s first symphony orchestra, the Palestine Symphony Orchestra, now called Israel Philharmonic). Huberman was impressed and organized a fundraiser to send Ivry to France for further studies. In Paris Gitlis went to the Conservatoire where his teachers were George Enescu and Jacques Thibaud. During WWII Gitlis moved to the UK (which probably saved his life) and performed many concerts for the troops. In the 1950s he traveled to the US, where he met Jascha Heifetz and, under the management of Sol Hurok, established himself as one of the premier violinists. Later in the 1950s he returned to France.

in Haifa. His parents had emigrated from Kamianets-Podilskyi in western Ukraine the previous year. Ivry took up the violin at the age of five, and at the age of eight played to Bronisław Huberman, the famous Polish violinist who was visiting Palestine (several years later, in 1936, Huberman founded Israel’s first symphony orchestra, the Palestine Symphony Orchestra, now called Israel Philharmonic). Huberman was impressed and organized a fundraiser to send Ivry to France for further studies. In Paris Gitlis went to the Conservatoire where his teachers were George Enescu and Jacques Thibaud. During WWII Gitlis moved to the UK (which probably saved his life) and performed many concerts for the troops. In the 1950s he traveled to the US, where he met Jascha Heifetz and, under the management of Sol Hurok, established himself as one of the premier violinists. Later in the 1950s he returned to France.

Even though Gitlis played a wide contemporary repertoire (and had many pieces written for him), he was rather old-fashioned when playing the Romantics. You can hear it in this interpretation of César Franck’s Violin sonata which he played in 1998 with none other than Martha Argerich (this is a live recording). Gitlis was then 78. He died in Paris on December 24th of 2020 at the age of 98.

Several composers were born this week, Ernst Krenek, Leonard Bernstein and Karlheinz Stockhausen among them. Claude Debussy, who was born on this day in 1862, 160 years ago has a special place in our heart. Check out our library, it has about 250 recordings of Debussy’s works, so if you wish to celebrate him today, browse it and find something to your liking. It’s very much worth it.Permalink

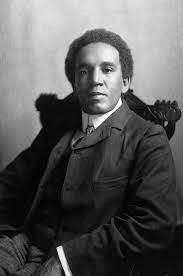

This Week in Classical Music: August 15, 2022. Coleridge-Taylor and Lili Boulanger. Two composers, whose music has probably been performed more often in the last two years than during all the years since it has been written, were born this week: Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, a composer of Afro-British origins, and Lili Boulanger, a French female composer. Coleridge-Taylor was born in London on August 15th of 1875. His mother was English, his father – a descendant of freed American slaves who settled in Sierra Leone. His father returned to Africa before Samuel was born, and his mother named him Samuel Coleridge Taylor after the Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. They lived with his mother’s father in a family that loved and played music, and it was recognized early on that Samuel was musically talented. Later, he was helped by Edward Elgar, who recommended him to the “Three Choirs Festival,” a music festival which rotates among three cathedrals, Worcester, Gloucester, and Hereford and takes its name from the choirs of these cathedrals (the festival is still going strong today). In 1898-1900 Coleridge-Taylor composed three cantatas under the name of The Song of Hiawatha. They became very popular, especially the first part, Hiawatha's Wedding Feast. In 1904 Coleridge-Taylor went on a tour of the United State and was received in the White House by Theodore Roosevelt. He toured the US and Canada in 1906 and the US again in 1910, visiting New York, Boston, Detroit, St-Louis, and other major cities. For many years Coleridge-Taylor was the conductor of the Handel Society of London. He died September 1st of 1912 of pneumonia, at just 37 years old. Here’s Coleridge-Taylor’s Hiawatha's Wedding Feast. Malcolm Sargent conducts the Royal Choral Society and the Philharmonia Orchestra. While it’s not clear to us why Coleridge-Taylor is sometimes called "the African Mahler" we sure are glad that his piece is not considered a cultural appropriation.

during all the years since it has been written, were born this week: Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, a composer of Afro-British origins, and Lili Boulanger, a French female composer. Coleridge-Taylor was born in London on August 15th of 1875. His mother was English, his father – a descendant of freed American slaves who settled in Sierra Leone. His father returned to Africa before Samuel was born, and his mother named him Samuel Coleridge Taylor after the Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. They lived with his mother’s father in a family that loved and played music, and it was recognized early on that Samuel was musically talented. Later, he was helped by Edward Elgar, who recommended him to the “Three Choirs Festival,” a music festival which rotates among three cathedrals, Worcester, Gloucester, and Hereford and takes its name from the choirs of these cathedrals (the festival is still going strong today). In 1898-1900 Coleridge-Taylor composed three cantatas under the name of The Song of Hiawatha. They became very popular, especially the first part, Hiawatha's Wedding Feast. In 1904 Coleridge-Taylor went on a tour of the United State and was received in the White House by Theodore Roosevelt. He toured the US and Canada in 1906 and the US again in 1910, visiting New York, Boston, Detroit, St-Louis, and other major cities. For many years Coleridge-Taylor was the conductor of the Handel Society of London. He died September 1st of 1912 of pneumonia, at just 37 years old. Here’s Coleridge-Taylor’s Hiawatha's Wedding Feast. Malcolm Sargent conducts the Royal Choral Society and the Philharmonia Orchestra. While it’s not clear to us why Coleridge-Taylor is sometimes called "the African Mahler" we sure are glad that his piece is not considered a cultural appropriation.

Lili Boulanger’s life was even shorter than Coleridge-Taylor’s: she died of tuberculosis at the age of 24. Boulanger, like Coleridge-Taylor, was also born (on August 21st of 1893) into a musical family, but of a much higher social status: her father, Ernest Boulanger, was a noted pianist, composer and conductor who counted Ambroise Thomas, Charles Gounod and Gabriel Fauré among his friends. Lili’s mother was born in St.-Petersburg, probably an illegitimate daughter of a Russian aristocrat; she studied singing in the St.-Petersburg Conservatory, moved to Paris at the age of 20, and soon became Ernest’s wife (he was then 62, she was 21). When Lili was two years old, Fauré discovered that she had perfect pitch. Also at the age of two, Lili got ill with pneumonia, which compromised her immune system for the rest of her short life. She attended some classes at the Paris Conservatoire (her frail health didn’t allow her to attend them all), and in 1913 won the coveted Prix de Rome for composition with the cantata Faust et Hélène, the first woman to do so (her father won it in 1835 but her talented sister Nadia who would become one of the most influential music teachers of the 20th century, failed to do so, coming in second; Nadia did win several First prizes, though). Lili went to Rome but return to Paris soon after as WWI broke out. She went back in 1916 for several months; in Rome she started working on a five-act opera La princesse Maleine and several other pieces but again returned to Paris, this time because her health was deteriorating. Her last piece, Pie Jesu for soprano, string quartet, harp and organ, was dedicated to her sister Nadia. Lile died on March 15, 1918 (Claude Debussy died ten days later). Here’s Pie Jesu, performed by the soprano Isabelle Sabrié, Eric Lebrun (organ), Francis Pierre (harp), and the strings.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: August 8, 2022. Seven composers. Yes, that many, all interesting, none of them great, at least in our opinion, and three of them French. Cécile Chaminade, one of the few women composers of the 19th century, and André Jolivet were born on August 8th and both in Paris, Chaminade in 1857, Jolivet in 1905. Reynaldo Hahn, a songwriter and Proust’s friend,was born on August 9th of 1874 in Caracas but spent his adult life in France. You can read about all three here.

in France. You can read about all three here.

The Russian composer Alexander Glazunov was born on August 10th of 1865. He wrote a wonderful Violin concerto and a very popular ballet, Raymonda. He also wrote eight complete symphonies (he never finished his ninth), two piano concertos and much more. Outside of Russia very little of this music is performed or broadcast. But Glazonov was very important as a public cultural figure and a supporter of classical music in Russia and the early Soviet Union. He became the Director of the St-Petersburg’s Conservatory in 1905 and served in that position until 1928, one of the few administrators who wasn’t fired after the revolution of 1917, most likely because Glazunov was friends with Anatoly Lunacharsky, Soviet Union’s first minister of education and culture. In 1928 Glazunov was invited to Vienna to a composer’s competition, organized to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Schubert’s death. He was allowed to go (again thanks to Lunacharsky) and decided not to return to Russia. He eventually settled in Paris and died in 1936. Here’s a typical Glazunov’s piece, a symphonic poem Sten’ka Razin, which extensively uses the theme from the Song of the Volga Boatmen (actually, barge haulers, who pulled barges by a rope). In Russian this song is called Эй, ухнем, usually and inaccurately translated as Yo, heave-ho!. The song was made famously by the great Russian bass Feodor Shalyapin. The American bass Paul Robeson also had it in his repertoire and in 1941 Glenn Miller arranged the song for his orchestra – it became a hit. Here is Chaliapin’s recording with an unnamed orchestra from 1923 – the quality isn’t high, but Chaliapin’s voice comes through.

Heinrich Ignaz Biber, an Austrian-Bohemian composer, was born on August 12th of 1644. Read about him (and more on Jolivet) here. On the same day but 52 years later, in 1696, the English composer Maurice Greene was born in London. He’s the author of some of the most popular pieces of English church music, the anthems Hearken Unto Me, Ye Holy Children (here) and Lord, let me know mine end (here).

We have to admit that sometimes we do not understand the music of Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji, our seventh composer, especially his longer works. Sorabji, whose father was a Parsi from Bombay, was born on August 14th of 1892. We last wrote an entry about him nine years ago (here) and were reticent to come back to the topic. That said, his Piano Sonata no. 1, from 1919, is quite accessible, lasts only 22 minutes and has a reasonably developed form. Here it is, brilliantly performed by Marc-André Hamelin in a 1990 recording.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: August 8, 2022. Seven composers. Yes, that many, all interesting, none of them great, at least in our opinion, and three of them French. Cécile Chaminade, one of the few women composers of the 19th century, and André Jolivet were born on August 8th and both in Paris, Chaminade in 1857, Jolivet in 1905. Reynaldo Hahn, a songwriter and Proust’s friend,was born on August 9th of 1874 in Caracas but spent his adult life in France. You can read about all three here.

in France. You can read about all three here.

The Russian composer Alexander Glazunov was born on August 10th of 1865. He wrote a wonderful Violin concerto and a very popular ballet, Raymonda. He also wrote eight complete symphonies (he never finished his ninth), two piano concertos and much more. Outside of Russia very little of this music is performed or broadcast. But Glazonov was very important as a public cultural figure and a supporter of classical music in Russia and the early Soviet Union. He became the Director of the St-Petersburg’s Conservatory in 1905 and served in that position until 1928, one of the few administrators who wasn’t fired after the revolution of 1917, most likely because Glazunov was friends with Anatoly Lunacharsky, Soviet Union’s first minister of education and culture. In 1928 Glazunov was invited to Vienna to a composer’s competition, organized to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Schubert’s death. He was allowed to go (again thanks to Lunacharsky) and decided not to return to Russia. He eventually settled in Paris and died in 1936. Here’s a typical Glazunov’s piece, a symphonic poem Sten’ka Razin, which extensively uses the theme from the Song of the Volga Boatmen (actually, barge haulers, who pulled barges by a rope). In Russian this song is called Эй, ухнем, usually and inaccurately translated as Yo, heave-ho!. The song was made famously by the great Russian bass Feodor Shalyapin. The American bass Paul Robeson also had it in his repertoire and in 1941 Glenn Miller arranged the song for his orchestra – it became a hit. Here is Chaliapin’s recording with an unnamed orchestra from 1923 – the quality isn’t high, but Chaliapin’s voice comes through.

Heinrich Ignaz Biber, an Austrian-Bohemian composer, was born on August 12th of 1644. Read about him (and more on Jolivet) here. On the same day but 52 years later, in 1696, the English composer Maurice Greene was born in London. He’s the author of some of the most popular pieces of English church music, the anthems Hearken Unto Me, Ye Holy Children (here) and Lord, let me know mine end (here).

We have to admit that sometimes we do not understand the music of Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji, our seventh composer, especially his longer works. Sorabji, whose father was a Parsi from Bombay, was born on August 14th of 1892. We last wrote an entry about him nine years ago (here) and were reticent to come back to the topic. That said, his Piano Sonata no. 1, from 1919, is quite accessible, lasts only 22 minutes and has a reasonably developed form. Here it is, brilliantly performed by Marc-André Hamelin in a 1990 recording.Permalink

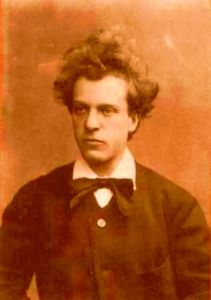

This Week in Classical Music: August 1, 2022. Hans Rott, Leonel Power. Today is the birthday of the Austrian composer Hans Rott; he was born in Braunhirschengrund, a suburb of Vienna, in 1858. A composer of obvious talent who lived a short and tragic life, he in a way anticipated Mahler. Both Bruckner and Mahler recognized him as a major talent. We wrote an entry about Rott, you can read it here. It seems that we’re not the only ones fascinated by Rott: his Symphony no. 1, the only one he completed, and some of his other works are being recorded on a regular basis. In the past two years a two-volume CD set was issued by the Capriccio label; it features the Gürzenich Orchestra Cologne, one of the two major Cologne orchestras, under the direction of Christopher Ward and contains practically all of Rott’s symphonic music.

Vienna, in 1858. A composer of obvious talent who lived a short and tragic life, he in a way anticipated Mahler. Both Bruckner and Mahler recognized him as a major talent. We wrote an entry about Rott, you can read it here. It seems that we’re not the only ones fascinated by Rott: his Symphony no. 1, the only one he completed, and some of his other works are being recorded on a regular basis. In the past two years a two-volume CD set was issued by the Capriccio label; it features the Gürzenich Orchestra Cologne, one of the two major Cologne orchestras, under the direction of Christopher Ward and contains practically all of Rott’s symphonic music.

This week is also a putative anniversary of Guillaume Dufay, who, according to some research was born on August 5th of 1397. We’ve written about this very important composer on a number of occasions (for example, here about his extensive travels around Europe). We’ve also written about his contemporary, another Franco-Flemish composer, Gilles Binchois (Dufay and Binchois were born about 25 miles from each other, the former in Beersel, the latter in Mons, both in modern day Belgium). Antoine Busnois ,who was a generation younger, is usually considered the third of the most consequential Franco-Flemish composers of the mid-15th century. The Franco-Flemish school was one of the two dominant music schools of the time, the other being developed in England (notice the absence of the Italians). Two English composers overshadowed the rest in the flourishing music scene: John Dunstaple and Leonel Power. Up till now we were amiss in not addressing Power’s life and music. Power was older than either Dunstaple or Dufay: he was born sometime between 1370 and 1385. There are few records of his life. Power’s name is first mentioned on a list of clerks of the household chapel of Thomas, Duke of Clarence: he’s listed as an instructor of the choristers (Thomas was a brother of Henry V, the great warrior-king of England immortalized by Shakespeare). In 1423 Power was mentioned as being admitted to the fraternity of Christ Church, Canterbury (the Canterbury cathedral). In 1439 Power became master of the choir at the cathedral. Not much else is known about his life. He died at Canterbury on June 5th of 1445. About 40 pieces of music are attributed to Power, many of them represented in the Old Hall Manuscript, a unique document compiled in the first half of the 15th century. We know of about eight of his masses, although two of them could have been written by Dunstaple: the styles of the two composers were similar, what the French called Contenance angloise, or English manner. Power was one of the first composers to create a unified mass cycle. To demonstrate Power’s music, here are two mass sections: Gloria and Credo. Both are performed by the Hilliard Ensemble.Permalink