Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

This Week in Classical Music: March 21, 2022. Catching Up: Haydn and more. Last week we celebrated Bach’s anniversary and didn’t have neither time nor space to even acknowledge several prominent composers and musicians; this week there are more, and the first one on our list is Franz Joseph Haydn, who was born on March 31st of 1732 in Rohrau, Austria. We love Haydn, have written about him on many occasions (here) and feel that he’s somewhat underappreciated these days. Haydn wrote 104 symphonies, some of supreme quality, he is considered the father of the string quartet, and we’ll go on a limb and say that some of Haydn’s piano sonatas are better than any ever written by Mozart. You can judge for yourself: here’s his sonata in E-flat Major, Hob. XVI:52, written in 1794, performed by Alfred Brendel. And here is the same sonata but in Glenn Gould’s rather idiosyncratic interpretation. It runs about 5 minutes faster than Brendel’s; you can also hear Gould singing.

several prominent composers and musicians; this week there are more, and the first one on our list is Franz Joseph Haydn, who was born on March 31st of 1732 in Rohrau, Austria. We love Haydn, have written about him on many occasions (here) and feel that he’s somewhat underappreciated these days. Haydn wrote 104 symphonies, some of supreme quality, he is considered the father of the string quartet, and we’ll go on a limb and say that some of Haydn’s piano sonatas are better than any ever written by Mozart. You can judge for yourself: here’s his sonata in E-flat Major, Hob. XVI:52, written in 1794, performed by Alfred Brendel. And here is the same sonata but in Glenn Gould’s rather idiosyncratic interpretation. It runs about 5 minutes faster than Brendel’s; you can also hear Gould singing.

Last week we missed anniversaries of Franz Schreker, who in the first quarter of the 20th century was, together with Richard Strauss, the most popular opera composer in the German-speaking world (Schreker was born on March 23rd of 1878). Another famous German-speaking opera composer, of a very different ear, Johann Adolph Hasse, was baptized on March 25th of 1699 (we don’t know his exact birthday). In the mid-18th century, Hasse’s opera seria were widely admired not only by the public but also by composers like Handel. The great Hungarian composer Béla Bartók was born on March 25th of 1881. And let’s not forget Pierre Boulez – the French composer, theoreticians, teacher, and conductor was born on March 26th of 1925.

This week, in addition to Haydn, we have: Sergei Rachmaninov, born on April 1st of 1873, the Spanish composer of the Renaissance Antonio de Cabezón, born March 30th of 1510 (here is his Pavana Italiana, performed by the organist Sebastiano Bernocchi); Ferruccio Busoni, born on April 1st of 1866 and another Italian of a very different era, Alessandro Stradella, on April 3rd of 1639. (Stradella’s life story was incredible, you may read about it here).

Among the conductors born this week (Willem Mengelberg, Pierre Monteux) there’s one with a particular interest to us, Christian Thielemann, who will turn 73 on April 1st. The reason is that he is rumored to become the Music Director of the Chicago Symphony, as 2023 is when the contract of the current Music Director, Riccardo Muti, expires. Despite Muti’s great popularity, we think replacing Miti with Thielemann would be an improvement, as the latter is superb in the core German-Austrian repertoire. Many political considerations come into play with such an important and visible position, and Thielemann has made a number of controversial statements (here’s an article in the Guardian on the subject). Of course, there are many other candidates in addition to Thielemann; we’ll see how it all plays out. So let’s conclude with Thielemann conducting Haydn. Here’s Thielemann with the Staatskapelle Dresden and the choir in the final section of Franz Joseph Haydn’s oratorio The Creation, Singt dem Herren, alle Stimmen! (Sing the Lord ye voices all).Permalink

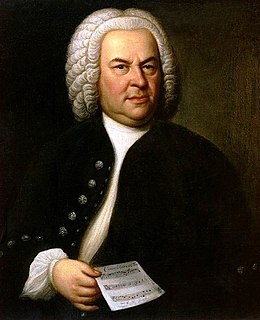

This Week in Classical Music: March 21, 2022. Johann Sebastian Bach. This is one birthday we cannot miss no matter what:Johann Sebastian Bach was born on this day in 1685. Last year we played Bach’s Cantata BWV 1, Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern(How beautifully the morning star shines), composed soon after Bach was made the Thomaskantor in Leipzig in 1723. Number 1 is a quirk of the BWV (Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis) catalogue, which lists Bach’s works by the genre and not in a chronological order: Cantatas come first, with the numbers from 1 to 224, then Motets, which are assigned numbers from 225 to 231, and so on. BWV 1, composed in 1725, was not Bach’s first cantata, it wasn’t even part of the first cycle of cantatas, which were composed in 1723-24. Today we’ll turn to BWV 2, Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh darein (Oh God, look down from heaven), composed for the second Sunday after Trinity and first performed on June 18th of 1724. Even though it has the second BWV number, it was preceded by more than 60 cantatas. Isn’t it time to create a more reasonable catalogue of Bach’s work? Whatever the number, it’s a wonderful piece which is performed here by Concentus Musicus Wien under the direction of Nikolaus Harnoncourt.

we played Bach’s Cantata BWV 1, Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern(How beautifully the morning star shines), composed soon after Bach was made the Thomaskantor in Leipzig in 1723. Number 1 is a quirk of the BWV (Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis) catalogue, which lists Bach’s works by the genre and not in a chronological order: Cantatas come first, with the numbers from 1 to 224, then Motets, which are assigned numbers from 225 to 231, and so on. BWV 1, composed in 1725, was not Bach’s first cantata, it wasn’t even part of the first cycle of cantatas, which were composed in 1723-24. Today we’ll turn to BWV 2, Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh darein (Oh God, look down from heaven), composed for the second Sunday after Trinity and first performed on June 18th of 1724. Even though it has the second BWV number, it was preceded by more than 60 cantatas. Isn’t it time to create a more reasonable catalogue of Bach’s work? Whatever the number, it’s a wonderful piece which is performed here by Concentus Musicus Wien under the direction of Nikolaus Harnoncourt.

We’ll stay with Bach in three more interpretations, all three by pianists who were also born this week. First, Egon Petri, a German of Dutch descent, he was born on March 23rd of 1881 in Hannover. A wonderful musician, he was a student and friend of Ferruccio Busoni, and helped his teacher in editing the 25-volume version of all Bach’s clavier compositions. And like Busoni, Egon Petri wrote several piano arrangements of Bach’s music. Here is one of them, the arrangement of Bach’s chorale prelude Vor deinen Thron tret ich hiermit (I Step Before Thy Throne), BWV 668. Petri recorded it in 1958.

Another brilliant German pianist, Wilhelm Backhaus was three years younger than Petri, he was born on March 26th of 1884 in Leipzig. Backhaus’s career was very long: he went on his first concert tour of England in 1900 and recorded Brahms’ Piano Concerto no. 2 with Karl Böhm in April of 1968, when he was 83, his formidable technique still quite in place. The problem with Backhaus (as with Böhm) is that he was a supporter of the Nazi regime and Adolf Hitler in particular. Because he had moved to Switzerland in 1930 (and became a Swiss citizen some years later) Backhaus escaped the denazification process and the stigma he had fully deserved. In a way he was no better than many Russian musicians who are being “canceled” all over Europe and the US today. Here’s Wilhelm Backhaus playing Bach’s French Suite No. 5 in G major, BWV 816. This recording was also made in 1958.

Lastly, the American pianist Byron Janis was born in McKeesport, Pennsylvania on March 24th of 1928 into a family of Jewish refugees from Russia (their original name was Yankelevich). As a kid, Janis studied with Josef and Rosina Lhévinne in New York and then became Vladimir Horowitz’s first pupil. He debuted with Rachmaninov’s Second Piano concerto at the age of 15 and played his first Carnegie concert at 20. In 1960, two years after Van Cliburn won the first Tchaikovsky competition, Janis toured the Soviet Union to tremendous success. He was also the first American to win a Grand Prix du Disque. Janis’s brilliant career was cut short by severe arthritis in both hands, which hit him in 1973. Here’s Byron Janis playing Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in A Minor, BWV 643. It’s an arrangement of an organ piece by Franz Liszt. The recording was made in 1948.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: March 14, 2022. Telemann. Just two weeks ago we complained that it’s difficult to find good music by Antonio Vivaldi other than the overexposed Four Seasons. Vivaldi wrote more than 500 concertos, some of them brilliant (clearly Johann Sebastian Bach thought so, as he transcribed a number of them) but many quite mediocre. The situation with Telemann is even more difficult. Georg Philipp Telemann, who was born on March 14th of 1681 in Magdeburg, was one of the most prolific composers in the history of Western music. He wrote more than 3000 compositions, including 1700 cantatas, of which 1400 are extant. Of course, much of the music was recycled, but Bach did the same on many occasions. How does one go through 1400 cantatas? How many of them have not been performed in the last 100 years? This problem confounds us every time we write about Telemann, and we addressed it directly a couple years ago. Though Telemann was very influential and highly regarded in the 18th century, his fame faded in the 19th, especially when musicologists like Spitta and Schweitzer started unfairly comparing him to Bach, even though during Telemann’s lifetime, and in the following decades, his music was favorably compared to that of Bach and Handel’s. Here is one of Telemann’s cantata’s, Du aber Daniel, gehe hin (Go thy way, Daniel). It is performed by the ensemble Cantus Cölln under the direction of Konrad Junghänel. We find the whole cantata very beautiful, the soprano aria Brecht, ihr müden Augenlieder especially so (it’s sung by Johanna Koslowsky).

Vivaldi wrote more than 500 concertos, some of them brilliant (clearly Johann Sebastian Bach thought so, as he transcribed a number of them) but many quite mediocre. The situation with Telemann is even more difficult. Georg Philipp Telemann, who was born on March 14th of 1681 in Magdeburg, was one of the most prolific composers in the history of Western music. He wrote more than 3000 compositions, including 1700 cantatas, of which 1400 are extant. Of course, much of the music was recycled, but Bach did the same on many occasions. How does one go through 1400 cantatas? How many of them have not been performed in the last 100 years? This problem confounds us every time we write about Telemann, and we addressed it directly a couple years ago. Though Telemann was very influential and highly regarded in the 18th century, his fame faded in the 19th, especially when musicologists like Spitta and Schweitzer started unfairly comparing him to Bach, even though during Telemann’s lifetime, and in the following decades, his music was favorably compared to that of Bach and Handel’s. Here is one of Telemann’s cantata’s, Du aber Daniel, gehe hin (Go thy way, Daniel). It is performed by the ensemble Cantus Cölln under the direction of Konrad Junghänel. We find the whole cantata very beautiful, the soprano aria Brecht, ihr müden Augenlieder especially so (it’s sung by Johanna Koslowsky).

A brief note on two recent concerts. Daniil Trifonov played last week in Chicago. That he is a pianist of huge talent becomes apparent almost immediately. He played a devilishly difficult, dense Szymanowski’s piano sonata no. 3, which seems to be influenced both by Schoenberg in his late tonal phase and Debussy. In Trifonov’s interpretation it became live, floating and very pianistic. Debussy (Pour le Piano) followed and then Prokofiev’s Sarcasms. Ukraine is on our mind: both the Polish Szymanowski and the Russian Prokofiev were born there. The second half of the concert was taken by Brahm’s enormous and somewhat unwieldy 3rd piano sonata. Brahms was just 20 when he wrote it and clearly it’s not his greatest composition but somehow Trifonov made it interesting to listen to. Trifonov is one of the most remarkable pianists on stage today and the concert was exhilarating. As one could’ve guessed, it has not been reviewed in the Chicago Tribune. The good news is that there were many young people in the audience.

A very different concert series took place several days later when Herbert Blomstedt came to town. Blomstedt is 94 and looks his age; he suffers from arthritis and walks slowly. Blomstedt conducted the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in three concerts, with Mozart’s Piano Concerto no. 17 in the first half and Bruckner’s Fourth Symphony in the second. Martin Helmchen was the soloist in the Mozart, and he played well (we’d love to hear him in a recital); Blomstedt held everything together. But of course, the important part came later. The Fourth Symphony is one of Bruckner’s more popular pieces, it’s the one with the famous Scherzo for the third movement. There were some issues in the brass section (is it still the best in the world?) but those were minor. Blomstedt, with his small gestures, managed to propel the symphony forward, despite its many stops, turns and repetitions. All climaxes were thrilling and overall it was a marvelous performance. The score book rested in front of Blomstedt on the stand, its red cover visible. It was never opened: Blomstedt conducted the whole 70-minute symphony from memory. The man is 94! The ovation was long, Blomstedt brought up different sections of the orchestra, all greeted with great applause. At the end Blomstedt patted the score, indicating that it’s Bruckner who should be applauded. How very true. Once again, there were many young people in the hall. Is there still hope for classical music?Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: March 7, 2022. War in Ukraine. We find it very difficult to write about music amidst the barbaric aggression of Russia against Ukraine. Putin’s unprovoked war against a country of 40 million is a watershed moment in European history: there hasn’t been a war of this scale since the fall of the Nazis. Putin clearly is a war criminal: his forces bombard civilian areas, schools, kindergartens, and we hope that, like Slobodan Milošević of Serbia, he will end up at the International Criminal Court in the Hague. The war is a humanitarian catastrophe, and Western response was swift and unified, with sanctions against Russia and aide to Ukraine. Music administrators around the world also got into the game, firing Valery Gergiev, Anna Netrebko and Denis Matsuyev from main stages and theaters of Europe and America after they refused to sign letters condemning Putin’s invasion. While we find these artists’ support of Putin and his regime reprehensible, we are somewhat ambivalent about what seems like a mob action against them. On the one hand we’re glad to see Gergiev gone (we also happen to think that he is overrated as conductor). But Gergiev has been close to Putin for decades. Why didn’t we see any action when Putin illegally annexed Ukrainian Crimea, with Gergiev’s full-throated support? Putin has committed war crimes before: he was the main enabler of Syria’s dictator Assad, and it was his, Putin’s, warplanes that bombed hospitals in Aleppo. Why wasn’t Gergiev fired back then? Is it because Syrian lives matter less than Ukrainian? As for Netrebko, she did support Putin’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine, but it seems that her main fault is that Putin likes her a lot. Netrebko was not the only one who supported Putin back in 2014: more than five hundred (!) Russian cultural luminaries signed a letter in support of the annexation of Crimea, the famous violist Yuri Bashmet and violinist Vladimir Spivakov among them. Since the current war had started, Spivakov and several other signed a meek letter against it, but not Bashmet. Will all “unrepented” musicians be banned from playing in the West? As we noted above, we don’t have a strong opinion about actions against Putin’s artists but find several things troubling. Is it OK to require political loyalty (or, in this case, disloyalty) statements from artists? Why do we treat artist differently, and in a seemingly arbitrary way? Of course, these questions have been asked before, when ardent Hitler’s supporters and Nazi party members Herbert von Karajan and Karl Böhm were quickly denazified and then accepted in the West while clearly not as culpable Wilhelm Furtwängler was not. All this pales compared to the war catastrophe and Putin’s evil, but the question of artists, politics and ethics are important and we’ll have to deal with them in years to come.

war against a country of 40 million is a watershed moment in European history: there hasn’t been a war of this scale since the fall of the Nazis. Putin clearly is a war criminal: his forces bombard civilian areas, schools, kindergartens, and we hope that, like Slobodan Milošević of Serbia, he will end up at the International Criminal Court in the Hague. The war is a humanitarian catastrophe, and Western response was swift and unified, with sanctions against Russia and aide to Ukraine. Music administrators around the world also got into the game, firing Valery Gergiev, Anna Netrebko and Denis Matsuyev from main stages and theaters of Europe and America after they refused to sign letters condemning Putin’s invasion. While we find these artists’ support of Putin and his regime reprehensible, we are somewhat ambivalent about what seems like a mob action against them. On the one hand we’re glad to see Gergiev gone (we also happen to think that he is overrated as conductor). But Gergiev has been close to Putin for decades. Why didn’t we see any action when Putin illegally annexed Ukrainian Crimea, with Gergiev’s full-throated support? Putin has committed war crimes before: he was the main enabler of Syria’s dictator Assad, and it was his, Putin’s, warplanes that bombed hospitals in Aleppo. Why wasn’t Gergiev fired back then? Is it because Syrian lives matter less than Ukrainian? As for Netrebko, she did support Putin’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine, but it seems that her main fault is that Putin likes her a lot. Netrebko was not the only one who supported Putin back in 2014: more than five hundred (!) Russian cultural luminaries signed a letter in support of the annexation of Crimea, the famous violist Yuri Bashmet and violinist Vladimir Spivakov among them. Since the current war had started, Spivakov and several other signed a meek letter against it, but not Bashmet. Will all “unrepented” musicians be banned from playing in the West? As we noted above, we don’t have a strong opinion about actions against Putin’s artists but find several things troubling. Is it OK to require political loyalty (or, in this case, disloyalty) statements from artists? Why do we treat artist differently, and in a seemingly arbitrary way? Of course, these questions have been asked before, when ardent Hitler’s supporters and Nazi party members Herbert von Karajan and Karl Böhm were quickly denazified and then accepted in the West while clearly not as culpable Wilhelm Furtwängler was not. All this pales compared to the war catastrophe and Putin’s evil, but the question of artists, politics and ethics are important and we’ll have to deal with them in years to come.

Several great composers were born this week, among them Maurice Ravel, Arthur Honegger and Hugo Wolf. We’ll get back to them at a later date.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: February 28, 2022. Chopin and Vivaldi. The great Polish composer Frédéric Chopin was born this week, on March 1st of 1810. His works form the core of the classical piano repertoire and have been performed continuously from the moment they were premiered, often by Chopin himself. Musical tastes change in waves, one composer comes to the fore and then recedes only to come back decades later. These days it feels like the music of Chopin with all its full-blooded romanticism is, if not in nadir, then clearly in descent: the time of Arthur Rubinstein, Vladimir Horowitz or the young Maurizio Pollini has passed. But as it has never left the concert stage (and never will), it still has its champions. One of them is a 26-year-old Canadian pianist Jan Lisiecki. He is of the Polish descent and that may have influenced his musical tastes, as in addition to playing a lot of Chopin he promotes the music of Paderewski. Lisiecki clearly feels an affinity with the country of his ancestors, he performs there often and had his first CD issued by the Polish Fryderyk Chopin Institute. He’s one of the very few pianists these days who can build a whole program around the music of Chopin. Recently, he brought one such program to Chicago. It was quite unusual: he played all twelve Etudes, op. 10, but not straight, as they are usually performed, but mixing them with eleven Nocturnes, six Etudes and six Nocturnes in the first half, and six Etudes and five Nocturnes after the intermission. It was an excellent concert: even if one may quibble with some interpretations, Lisiecki clearly has a vision of how this music should be played, he has great technique, wonderful touch and singing tone. Orchestra Hall, the venue where he performed, was full, an unusual occurrence in these Covid days, and, what’s important is that there were many young people in the audience. Lisiecki seems to have a following, and that he’s tall, slim and good looking, reminding one of the young Van Cliburn, clearly doesn’t hurt. There was another matter about this concert worth mentioning: it hasn’t been reviewed by either one of Chicago’s main newspapers. These days it’s not surprising: Chicago Tribune, the home to Claudia Cassidy, and the newspaper that published John von Rhein’s reviews for 40 years, doesn’t even have a music critic on its staff that could credibly write about classical concerts. Kyle MacMillan, whose reviews the Chicago Tribune publishes from time to time, is a free-lance writer. Chicago Sun Times is no different. This attests to the current sorry state of classical music in our society.

of the classical piano repertoire and have been performed continuously from the moment they were premiered, often by Chopin himself. Musical tastes change in waves, one composer comes to the fore and then recedes only to come back decades later. These days it feels like the music of Chopin with all its full-blooded romanticism is, if not in nadir, then clearly in descent: the time of Arthur Rubinstein, Vladimir Horowitz or the young Maurizio Pollini has passed. But as it has never left the concert stage (and never will), it still has its champions. One of them is a 26-year-old Canadian pianist Jan Lisiecki. He is of the Polish descent and that may have influenced his musical tastes, as in addition to playing a lot of Chopin he promotes the music of Paderewski. Lisiecki clearly feels an affinity with the country of his ancestors, he performs there often and had his first CD issued by the Polish Fryderyk Chopin Institute. He’s one of the very few pianists these days who can build a whole program around the music of Chopin. Recently, he brought one such program to Chicago. It was quite unusual: he played all twelve Etudes, op. 10, but not straight, as they are usually performed, but mixing them with eleven Nocturnes, six Etudes and six Nocturnes in the first half, and six Etudes and five Nocturnes after the intermission. It was an excellent concert: even if one may quibble with some interpretations, Lisiecki clearly has a vision of how this music should be played, he has great technique, wonderful touch and singing tone. Orchestra Hall, the venue where he performed, was full, an unusual occurrence in these Covid days, and, what’s important is that there were many young people in the audience. Lisiecki seems to have a following, and that he’s tall, slim and good looking, reminding one of the young Van Cliburn, clearly doesn’t hurt. There was another matter about this concert worth mentioning: it hasn’t been reviewed by either one of Chicago’s main newspapers. These days it’s not surprising: Chicago Tribune, the home to Claudia Cassidy, and the newspaper that published John von Rhein’s reviews for 40 years, doesn’t even have a music critic on its staff that could credibly write about classical concerts. Kyle MacMillan, whose reviews the Chicago Tribune publishes from time to time, is a free-lance writer. Chicago Sun Times is no different. This attests to the current sorry state of classical music in our society.

Antonio Vivaldi was born March 4th of 1678 in Venice. We are on a quest to find great pieces by Vivaldi that are not the Four Seasons. Here’s one of our discoveries, the Intorduzioni, the motets for solo voice, choir and orchestra. There are eight of them altogether, and Canta in Prato, RV 636 is one of them. It consists of three parts, about six minutes of music in total. The English soprano Margaret Marshall is the solo. English Chamber Orchestra and John Alldis Choir are conducted by Vittorio Negri (here).Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: February 21, 2022. Handel and more. George Frideric Handel, one of the greatest composers of the Baroque era, was born on February 23rd of 1685. Interestingly, till about the second half of the 20th century, he was known mostly for his several orchestral works and oratorios, Messiah being the most famous. In reality, Handel was the greatest opera composer of the era and had written music in all genres of the time, including instrumental, chamber and vocal. His reputation is still lower outside of the English-speaking world, where it is on par with Bach’s. We’ve written about Handel many times, here, for example two years ago, with his opera Rodelinda being the focus, and here, about his early years in London. Handel was a fascinating figure, worldly and sophisticated; he was also a virtuoso performer on the keyboard and the violin and wrote for both instruments. Here, for example, is the keyboard Suite in D minor HWV436, it comes from the mid-1720s. It’s performed by the German pianist Ragna Schirmer.

Interestingly, till about the second half of the 20th century, he was known mostly for his several orchestral works and oratorios, Messiah being the most famous. In reality, Handel was the greatest opera composer of the era and had written music in all genres of the time, including instrumental, chamber and vocal. His reputation is still lower outside of the English-speaking world, where it is on par with Bach’s. We’ve written about Handel many times, here, for example two years ago, with his opera Rodelinda being the focus, and here, about his early years in London. Handel was a fascinating figure, worldly and sophisticated; he was also a virtuoso performer on the keyboard and the violin and wrote for both instruments. Here, for example, is the keyboard Suite in D minor HWV436, it comes from the mid-1720s. It’s performed by the German pianist Ragna Schirmer.

Five pianists have anniversaries this week, four of them were Russian-born but none spent their life in Russia: Benno Moiseiwitsch, a British pianist, was born in Odessa, then in the Russian Empire into a Jewish family, on February 22nd of 1890; then three day later is the anniversary of another Brit, this time a “real” one but also Jewish, Dame Myra Hess. Nikita Magaloff, of Russian-Georgian descent who spent much of his life in Switzerland, was born in Saint-Petersburg on February 21st of 1912. Lazar Berman, another Russian (also Jewish), was born on the 26th the month in 1930 in Leningrad (now St.-Petersburg) and, finally, yet another Russian-born pianist, Arcadi Volodos (no, this one is not Jewish) was born on February 24th of 1972, also in Leningrad; these days Volodos lives in Spain. None of these pianists were very interested in the music of Handel, the only example we could find of one of them playing his music is an old, scratchy but interesting recording made in 1937 by the famous Hungarian violinist Joseph Szigeti who was accompanied by Nikita Magaloff. It is Handel’s Violin Sonata in D Major, HWV371, composed later in Handel’s life in 1750 (here).

We also celebrate another Soviet-born musician, a violinist. Gidon Kremer will turn 75 on the 27th, he was born on that day in 1947 in Riga, Latvia. Latvia, now independent, was then part of the Soviet Union; Kremer studied at the Moscow Conservatory with David Oistrakh, became a laureate of several major competitions, and then won the Tchaikovsky Competition in 1970. In 1980 Kremer emigrated from the Soviet Union and settled in Germany. In 1997 Kremer founded a chamber orchestra called Kremerata Baltica. Even though Kramer’s repertoire is very broad (he’s a big promoter of contemporary music), as far as we know he hasn’t recorded a single violin sonata of Handel. So instead we’ll hear Kremer playing a violin sonata by Handel’s contemporary, Johann Sebastian Bach. Here’s Bach Violin Sonata No.3 in C major BWV 1005, written in 1720. The recording was made in 1981.Permalink