Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

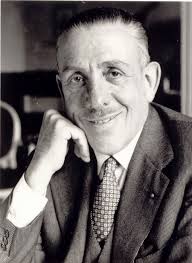

This Week in Classical Music: July 26, 2021. Di Stefano. We missed a big date, Giuseppe Di Stefano’s 100th anniversary, by two days: he was born in a small village of Motta Sant’Anastasia, near Catania in Sicily on July 24th of 1921. His family moved all the way north to Milan when Giuseppe was six. At the age of 20 he began voice studies with Luigi Montesanto, a fine baritone and teacher. The war interrupted his career as Di Stefano was conscripted. The regiment’s doctor, having heard him singing, gave him a medical dispensation, saying that he would better serve Italy as singer than a soldier. The regiment was sent to the Russian front where most of the soldiers, including the doctor, were killed. In 1943 Di Stefano fled to Switzerland, was interned there but then released. In Lausanne he made his first recordings. He returned to Italy in 1946 and soon after made his début at the Teatro Municipale, Reggio nell’Emilia, as Massenet’s Des Grieux. A year later, in 1947, he sang at La Scala. In 1948 he made his Metropolitan debut as the Duke in Rigoletto. He was noticed almost immediately, with a critic comparing the 27-year-old tenor with Beniamino Gigli and praising his warm, sensual timbre. A lyric tenor, in his early career he sang mostly lighter roles. By 1957 he moved to heavier “spinto” and even dramatic tenor roles, such as Don José in Carmen, Canio in Pagliacci, Turiddu in Cavalleria rusticana, and Radames in Aida. With this, his voice lost some of its shine and got rougher; still, it was spectacular. Rudolf Bing, the General Manager of the Metropolitan Opera, who knew his singers, said: “The most spectacular single moment in my observation year had come when I heard his diminuendo on the high C in "Salut! demeure" in Faust: I shall never as long as I live forget the beauty of that sound." You can listen to it here, and while the whole aria is sung beautifully, it’s literally breathtaking at around 5’05”. This was a live recording made in 1950 in San Francisco during the War Memorial Opera House Concerts which were then broadcast on NBC. Gaetano Merola conducts the (substandard) San Francisco Opera Association Orchestra.

near Catania in Sicily on July 24th of 1921. His family moved all the way north to Milan when Giuseppe was six. At the age of 20 he began voice studies with Luigi Montesanto, a fine baritone and teacher. The war interrupted his career as Di Stefano was conscripted. The regiment’s doctor, having heard him singing, gave him a medical dispensation, saying that he would better serve Italy as singer than a soldier. The regiment was sent to the Russian front where most of the soldiers, including the doctor, were killed. In 1943 Di Stefano fled to Switzerland, was interned there but then released. In Lausanne he made his first recordings. He returned to Italy in 1946 and soon after made his début at the Teatro Municipale, Reggio nell’Emilia, as Massenet’s Des Grieux. A year later, in 1947, he sang at La Scala. In 1948 he made his Metropolitan debut as the Duke in Rigoletto. He was noticed almost immediately, with a critic comparing the 27-year-old tenor with Beniamino Gigli and praising his warm, sensual timbre. A lyric tenor, in his early career he sang mostly lighter roles. By 1957 he moved to heavier “spinto” and even dramatic tenor roles, such as Don José in Carmen, Canio in Pagliacci, Turiddu in Cavalleria rusticana, and Radames in Aida. With this, his voice lost some of its shine and got rougher; still, it was spectacular. Rudolf Bing, the General Manager of the Metropolitan Opera, who knew his singers, said: “The most spectacular single moment in my observation year had come when I heard his diminuendo on the high C in "Salut! demeure" in Faust: I shall never as long as I live forget the beauty of that sound." You can listen to it here, and while the whole aria is sung beautifully, it’s literally breathtaking at around 5’05”. This was a live recording made in 1950 in San Francisco during the War Memorial Opera House Concerts which were then broadcast on NBC. Gaetano Merola conducts the (substandard) San Francisco Opera Association Orchestra.

Walter Legge, the famous record producer, put Di Stefano and Maria Callas together to record many popular Italian operas. One of them, the 1953 recording of Tosca, with Titto Gobbi as Scarpia, is considered one of the best opera recordings ever made. Here’s a 12-minute excerpt from Act I, starting with “Mario! Mario! Quale occhi" from that legendary recording. Di Stefano and Callas are accompanied by the Orchestra del Teatro alla Scala under the direction of Victor de Sabata.

Di Stefano was a bon-vivant, he smoked and partied, had many lovers (he had an affair with his singing partner, Maria Callas), and sometimes – too often, as far as Rudolf Bing was concerned – failed to show up for rehearsals: Bing banned him from the Met for three years. All of that probably affected his career, which at its height was brief: his voice was already in decline in the late 1950s; Di Stefano himself blamed allergies. He rarely performed after a disastrous Otello in Pasadena in 1966. Di Stefano had a house in Kenia. On December 3rd of 2004 he was robbed and beaten there; perpetrators were never found. He never fully recovered from his injuries. Giuseppe Di Stefano died in his home in Lecco on Lake Como, on March 3rd of 2008 at the age of 86.

Riccardo Muti, a wonderful Italian conductor and the Music Director of the Chicago Symphony, will turn 80 on July 28th. He deserves a full entry, which is forthcoming.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: July 19, 2021. Francis Poulenc. We’re publishing an entry by a guest contributor, Aleah Fitzwater in which she writes about one of her favorite composers, Francis Poulenc. A flute teacher, Aleah especially likes Poulenc’s Flute Sonata. Here it is, in an excellent performance by Emmanuel Pahud, flute, and Éric Le Sage, piano.

Francis Poulenc. A flute teacher, Aleah especially likes Poulenc’s Flute Sonata. Here it is, in an excellent performance by Emmanuel Pahud, flute, and Éric Le Sage, piano.

The Perplexing Francis Poulenc.

Francis Poulenc was born on January 7th of 1899 in Paris. One of France’s most popular composers, he was mainly self-taught. Many listeners feel that as a melodist, he was Faure’s greatest successor. In his music Poulenc was inspired by Stravinsky and Satie, and later by Auric and Milhaud.

Style. Poulenc’s style evolved considerably during his career, from very simplistic, direct pieces early on to much more complex compositions written after World War II. According to Seattlechambermusic.org, Poulenc struggled with both manic and depressive states. This may have led to his unique and eclectic collection of sounds and styles.

Perhaps his struggles with his identity and mental health are also part of the reason why he destroyed most of his earliest compositions. I can’t help but wonder what they may have sounded like. Many of Poulenc’s pieces took on a dark and haunting theme, such as a piece for solo piano, titled Processional pour la crémation d'un mandarin, one of the pieces that he destroyed.

An Early Start. Poulenc started writing when he was just 15 years old, in 1914. As we mentioned, none of the composition written in the following three years survive. His first popular piece was written when he was only 18 years old.

Studying with Ricardo Viñes. Ricardo Viñes was a pianist from Spain, with whom Poulenc studied. A well-regarded musician, Viñes gave premieres for many of this era’s composers, such as Ravel, Debussy and Satie; he was also their close friend. It is surprising to me that Poulenc studied with Vines, as he later joined a group that was at odds with Ravel’s style.

During Poulenc’s time with Vines, he was introduced to many composers, among them Satie and Auric. Vines helped Poulenc network and hone his art as a performing pianist.

Les Six. Les Six was a group of six French musicians. And yep! Their name pays homage to the nationalistic Russian group titled ‘The Five.’ This group (Les Six) was formed by Satie himself in the year 1919. The members of Les Six include Georges Auric, Louis Durey, Darius Milhaud, Arthur Honegger, Poulenc himself, and the only woman, Germaine Tailleferre.

Poulenc joined this group of composers and helped to collaborate on the 1920 album (fittingly named) L’Album des Six. Shortly after this, five of the six members (including Poulenc) worked together to create the collection titled Les Maries de la Tour Eiffel. In this collection, Poulenc wrote a polka, as well as the piece La Baigneuse de Trouville. The collaboration itself was an opera, which was rumored to have caused almost as much of a stir as The Rite of Spring did. The plotline is nothing short of odd. Some key points include a lion (who eats people), and a witchy child murderer. But hey, at least it sounds nice? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7zc2FirtReE (continue reading here). Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: July 12, 2021. Heinrich Isaac. Gerald Finzi, a British composer, Eugène Ysaÿe, a Belgian composer and virtuoso violinist, and Giovanni Bononcini, an Italian and Handel’s rival, were all born this week (on July 14th of 1901, July 16th of 1858 and July 18th of 1670 respectively). But we’d like to write about Heinrich Isaac, as we haven’t done so before. Isaac, a contemporary of Josquin des Prez and Jacob Obrecht, was born around 1450 in southern Flanders, probably in the Duchy of Brabant. As usually is the case with the composers of the era, little is known about his youth. He’s first mentioned in 1484 as a composer at the court of Duke Sigismund of Austria in Innsbruck. In 1485 he was already in Florence, singing (and probably composing) at the magnificent Baptistry, at the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, and the Basilica della Santissima Annunziata. Soon after, he entered the employ of Lorenzo de’ Medici the Magnificent, the de facto ruler of Florence during that time. Lorenzo didn’t have a formal chapel of singers, but Isaac was expected to set to music the poems by Lorenzo’s favorite authors and, as Professor Strohm writes, “to contribute generally to the musical life of the Medici household and the city.” Isaac stayed in Florence till 1496; after Lorenzo died in 1492, he came under the patronage of Lorenzo’s son Pietro de’Medici. Even though the Medicis were banished from Florence in 1494, the association with the family was quite beneficial to Isaac: when Lorenzo’s other son, Giovanni, was installed the Pope Leo X in 1513, he became Isaac’s patron in Rome. In the meantime, in 1496 he found employment in Vienna, at the chapel of Maximilian I, the future Holy Roman Emperor from the Habsburg family. By 1502 Isaac was back in Italy, first in Florence and then at the Este court of Ferrara, where he had hoped to find a job. To quote Strohm: “Josquin des Prez was chosen instead, although the court agent Gian d’Artiganova reported (2 September 1502) favourably about Isaac who ‘would compose whenever asked’ and not as he pleased like Josquin.” Isaac returned to Tyrol to join Maximilian’s court and served there till 1514. In 1515 Maximilian allowed Isaac to live in Florence while receiving a salary. He stayed there, composing for Maximilian, the Pope and the church of Santissima Annunziata. Isaac died in Florence on March 26th of 1517.

Italian and Handel’s rival, were all born this week (on July 14th of 1901, July 16th of 1858 and July 18th of 1670 respectively). But we’d like to write about Heinrich Isaac, as we haven’t done so before. Isaac, a contemporary of Josquin des Prez and Jacob Obrecht, was born around 1450 in southern Flanders, probably in the Duchy of Brabant. As usually is the case with the composers of the era, little is known about his youth. He’s first mentioned in 1484 as a composer at the court of Duke Sigismund of Austria in Innsbruck. In 1485 he was already in Florence, singing (and probably composing) at the magnificent Baptistry, at the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, and the Basilica della Santissima Annunziata. Soon after, he entered the employ of Lorenzo de’ Medici the Magnificent, the de facto ruler of Florence during that time. Lorenzo didn’t have a formal chapel of singers, but Isaac was expected to set to music the poems by Lorenzo’s favorite authors and, as Professor Strohm writes, “to contribute generally to the musical life of the Medici household and the city.” Isaac stayed in Florence till 1496; after Lorenzo died in 1492, he came under the patronage of Lorenzo’s son Pietro de’Medici. Even though the Medicis were banished from Florence in 1494, the association with the family was quite beneficial to Isaac: when Lorenzo’s other son, Giovanni, was installed the Pope Leo X in 1513, he became Isaac’s patron in Rome. In the meantime, in 1496 he found employment in Vienna, at the chapel of Maximilian I, the future Holy Roman Emperor from the Habsburg family. By 1502 Isaac was back in Italy, first in Florence and then at the Este court of Ferrara, where he had hoped to find a job. To quote Strohm: “Josquin des Prez was chosen instead, although the court agent Gian d’Artiganova reported (2 September 1502) favourably about Isaac who ‘would compose whenever asked’ and not as he pleased like Josquin.” Isaac returned to Tyrol to join Maximilian’s court and served there till 1514. In 1515 Maximilian allowed Isaac to live in Florence while receiving a salary. He stayed there, composing for Maximilian, the Pope and the church of Santissima Annunziata. Isaac died in Florence on March 26th of 1517.

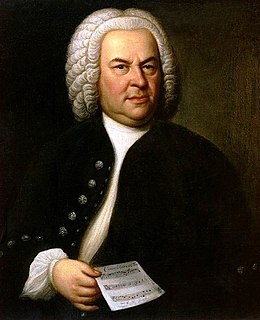

Isaac was tremendously prolific, composing masses, 36 of which survive, motets and songs. He was one of the few composers to work in the German language lands, and thus influenced musical development in those countries. Here is Virgo Prudentissima, composed by Isaac for the court of Maximilan I. It’s performed by the ensemble Stile Antico, a British group which is rather unique in that it performs without a conductor. And here is another motet, Innsbruck, Ich Muß Dich Lassen (Innsbruck, I must leave thee); as the one above it was written for Maximilian I. The motet is based on a popular song, also composed by Isaac; it was also used by Johann Sebastian Bach at least twice, in his Cantata BWV 97 In allen meinen Taten and Cantata BWV 117 Sei Lob und Ehr dem höchsten Gut. Innsbruck is performed by the ensemble Hofkapelle under the direction of Michael Procter.

We don't know what Heinrich Isaac looked like -- no portraits of his are extant. The picture above, painted by Albrecht Dürer in 1519, is of the Emperor Maximilian I, Isaac's generous patron.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: July 5, 2021. Mahler and Gedda. Gustav Mahler’s birthday is on July 7th. He was born in 1860 in Bohemia (then part of the Austria-Hungary, now the Czech Republic), into a poor German-speaking Jewish family. We’ve written about Mahler many times; his music was slow in acceptance, to a large extent because of its complexity and new nature, but also, in the 1930s and 1940s, for political and ethnic reasons. Mahler became extremely popular in the second half of the 20th century, but it seems that now, again, his music is fading somewhat. We think of it as a litmus test, this time more cultural than political. The changes are especially obvious in radio programming: there was a time when WFMT, a premier classical music station, would broadcasts his symphonies on a regular basis, and especially onhis birthday. Now you will only hear Mahler when WFMT runs special programs, such as old recorded concerts of the symphony orchestras or programs like Henry Fogel’s “Collectors’ Corner.” We don’t know the exact reasons for this – it’s difficult to imagine that WFMT just decided that people stopped loving Mahler’s music. We can only surmise that Mahler’s symphonies are too long and don’t allow for many commercial interruptions, that they are too complex (WFMT, like many other stations, has been trending toward simpler music for years), and that WFMT need more airtime for women composers. Of course, there may also be personal biases at play or other reasons we’re not aware of. But in the end, the results are obvious: Mahler’s music, if not directly banned, is relegated. This is unfortunate and, we hope, will be reversed in the future. In the meantime, here is the fourth movement, Adagio. Sehr langsam und noch zurückhaltend, from Mahler’s Symphony no. 9. Pierre Boulez conducts the Chicago Symphony.

Republic), into a poor German-speaking Jewish family. We’ve written about Mahler many times; his music was slow in acceptance, to a large extent because of its complexity and new nature, but also, in the 1930s and 1940s, for political and ethnic reasons. Mahler became extremely popular in the second half of the 20th century, but it seems that now, again, his music is fading somewhat. We think of it as a litmus test, this time more cultural than political. The changes are especially obvious in radio programming: there was a time when WFMT, a premier classical music station, would broadcasts his symphonies on a regular basis, and especially onhis birthday. Now you will only hear Mahler when WFMT runs special programs, such as old recorded concerts of the symphony orchestras or programs like Henry Fogel’s “Collectors’ Corner.” We don’t know the exact reasons for this – it’s difficult to imagine that WFMT just decided that people stopped loving Mahler’s music. We can only surmise that Mahler’s symphonies are too long and don’t allow for many commercial interruptions, that they are too complex (WFMT, like many other stations, has been trending toward simpler music for years), and that WFMT need more airtime for women composers. Of course, there may also be personal biases at play or other reasons we’re not aware of. But in the end, the results are obvious: Mahler’s music, if not directly banned, is relegated. This is unfortunate and, we hope, will be reversed in the future. In the meantime, here is the fourth movement, Adagio. Sehr langsam und noch zurückhaltend, from Mahler’s Symphony no. 9. Pierre Boulez conducts the Chicago Symphony.

Nicolai Gedda, born on July 11th of 1925 in Stockholm, was one of the best operatic tenors of the mid-20th century. Gedda had a rather unusual biography. He was born out of wedlock; his mother was a 17-year-old Swedish waitress, his father – an unemployed half-Russian, half-Swede. He was raised by his aunt on his father’s side, who was born in Riga, and her husband, Mikhail Ustinoff, a Russian Cossack (and a relative of the famous actor Peter Ustinov). Gedda’s biological parents lived in the same house, but he thought they were his aunt and uncle. Gedda grew up bilingual, speaking Swedish and Russian; he would later turn into a veritable polyglot, learning (and performing operas in) French, German, Italian, English, and Czech, in addition to his native Swedish and Russian. He studied singing in Stockholm with Carl Martin Oehman, a Swedish tenor and singing teacher, who “discovered” Jussi Björling. Gedda made his debut in the Royal Swedish Opera in 1951. Two years later he was already singing in La Scala (Don Ottavio in Mozart’s Don Giovanni). Through his meeting with Walter Legge, who was extremely impressed by Gedda’s singing, he got a recording contract with HMV (His Master’s Voice). In 1954, Gedda moved to Paris, where he sung at the Opéra and in many concerts and festivals. His Covent Garden debut followed the next year and, in 1957, he debuted at the Met, where he sung for 22 seasons. Gedda’s repertoire was remarkably broad: he sung Italian and Russian operas, the Frenchmen Gounod, Berlioz and Biset, he was great in Mozart and operas by the Soviet composers: Shostakovich’s Lady MacBeth of Mtsensk and Prokofiev’s War and Peace. He sung the role of Lohengrin and was a great proponent of the German Lied and Russian Orthodox songs. Gedda sung beautifully well into his 70s. Here is Nicolai Gedda brilliantly singing the aria Salut! Demeure chaste et pure from Gounod’s Faust in the 1978 recording. Andre Cluytens is conducting the Paris Opera orchestra.Permalink

tenors of the mid-20th century. Gedda had a rather unusual biography. He was born out of wedlock; his mother was a 17-year-old Swedish waitress, his father – an unemployed half-Russian, half-Swede. He was raised by his aunt on his father’s side, who was born in Riga, and her husband, Mikhail Ustinoff, a Russian Cossack (and a relative of the famous actor Peter Ustinov). Gedda’s biological parents lived in the same house, but he thought they were his aunt and uncle. Gedda grew up bilingual, speaking Swedish and Russian; he would later turn into a veritable polyglot, learning (and performing operas in) French, German, Italian, English, and Czech, in addition to his native Swedish and Russian. He studied singing in Stockholm with Carl Martin Oehman, a Swedish tenor and singing teacher, who “discovered” Jussi Björling. Gedda made his debut in the Royal Swedish Opera in 1951. Two years later he was already singing in La Scala (Don Ottavio in Mozart’s Don Giovanni). Through his meeting with Walter Legge, who was extremely impressed by Gedda’s singing, he got a recording contract with HMV (His Master’s Voice). In 1954, Gedda moved to Paris, where he sung at the Opéra and in many concerts and festivals. His Covent Garden debut followed the next year and, in 1957, he debuted at the Met, where he sung for 22 seasons. Gedda’s repertoire was remarkably broad: he sung Italian and Russian operas, the Frenchmen Gounod, Berlioz and Biset, he was great in Mozart and operas by the Soviet composers: Shostakovich’s Lady MacBeth of Mtsensk and Prokofiev’s War and Peace. He sung the role of Lohengrin and was a great proponent of the German Lied and Russian Orthodox songs. Gedda sung beautifully well into his 70s. Here is Nicolai Gedda brilliantly singing the aria Salut! Demeure chaste et pure from Gounod’s Faust in the 1978 recording. Andre Cluytens is conducting the Paris Opera orchestra.Permalink

- Which solo instrument?

- When was it written?

This Week in Classical Music: June 28, 2021. A Guest Entry: Bach Partita in E Minor for Solo Flute. Today we’re publishing an entry by a guest, Aleah Fitzwater, a studio flute teacher and music blogger who’s analyzing Bach’s Partita for Solo Flure. You can read more about Aleah at the bottom of this entry. She recommends several recordings of the partita; you can also listen to it here in the performance by James Galway.

and music blogger who’s analyzing Bach’s Partita for Solo Flure. You can read more about Aleah at the bottom of this entry. She recommends several recordings of the partita; you can also listen to it here in the performance by James Galway.

Bach Partita in E Minor for Solo Flute

The Bach Partita in E minor (BWV 1013) is one of those pieces that you could spend years with, and not quite perfect. It is the Moonlight Sonata of flute pieces.

One might expect this piece to be accompanied by basso continuo, but it was just written for a solo instrument. Naturally, the next questions I would answer are as follows:

After diving into a little research, I discovered just how many unanswered questions still follow this piece.

A Piece Shrouded in Mystery

One of the many things that I love about this partita is the uncertainty of it all. Nobody is sure exactly when it was written.

Some historians even propose that BWV 1013 was originally intended for violin, though it is usually performed on flute today. They think it may have been for violin, because the piece has no breath marks. There are long stretches of phrases that would simply sound odd if broken, which leads to many challenges for the flutist. Others argue that the piece was written for flute, but influenced by trends in the violin music of the time (JSOR.org). But without so much as a title from JS Bach, how would we ever know?

Discovery

The piece was first discovered by Karl Straube, a well-known church musician and organist. He was actually the one who named it, not Johann Sebastian Bach. I have to wonder- What would Bach have called it instead? Perhaps the piece was untitled because it was unfinished, which begs the question:

Should it be played with basso continuo after all?

There is only one manuscript from the original time period. It can be estimated that it was written after the 1720’s, because of the style. That being said, historians are also unsure of the transcriptionist who penned this copy.

Movements

Allemande

The arpeggiations of the first movement strongly implies a chordal structure. It gives us the sense that there are multiple flutes (or a harpsichord) beneath the louder melody up top. Though it is somewhat technically challenging, when the Allemande is played correctly, it gives us a laid-back feeling, as if a shepherd were playing in a meadow.

Courante

The Partita’s second movement starts off with a sunny yellow color. The accented feeling from the higher note of each measure gives it a near-sassy attitude.

Sarabande

The tone of this Sarabande is melancholy yet regal. The delicacy at which Jean-Pierre Rampal plays it at is most demanding. This movement is simply too easy to overdo. The player needs an entire reset both physically and emotionally, between the Courante and the Sarabande. The piano sections of this movement sound like the softest crying.

Bourrée Anglais

The Bourrée Anglais, or, English dance, closes this partita with an energetic exclamation mark. This is both the fastest and most technically challenging of the five movements. Light-footed double tonguing and nimble thirds are crucial to pulling off the closing of this piece.

Recordings

I highly recommend this recording by Jean-Pierre Rampal https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_YOMtofcJRg as well as this recording by Pahud https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-LMni-U7Fiw . While there are recordings on wooden flutes that better capture the time period in which it was written, Rampal and Pahud’s recordings contain an impeccable emotional and dynamic sensitivity. In addition, Matvey Demin’s recording of the piece especially shines through in its tasteful ornamentations https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W6vrx5lWzDU

About the Author: Aleah Fitzwater is a studio flute teacher, and music blogger for https://scan-score.com/en/ and https://aleahfitzwater.com/ . In her free time, she enjoys arranging rock songs for flute, and cooking French cuisine. Permalink

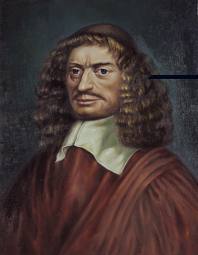

This Week in Classical Music: June 21, 2021. A Wrong Portrait. Some years ago we published an entry about an interesting early-Baroque Italian composer Giacomo Carissimi. We decided to include his portrait, as we often do when we write about a composer or a performer, so we searched the web and came up with the portrait you see to theleft. It was used on many sites, some quite established, for example, France Musique, a French national public music channel. Then some time ago we received an email from one of our listeners, who told us that the portrait is not of Carissimi at all. That was surprising, so we decided to research the matter. Sure enough, almost immediately we came across an old article by the musicologist Gloria Rose called A Portrait Called Carissimi. In this article Rose wrote about the origins of the portrait: it could be found at the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris as the frontispiece to a manuscript containing numerous works by Carissimi. Moreover, this is the only surviving portrait of the composer: while Giuseppe Ottavio Pitoni, a composer and music theorist who lived in Rome in the first half of the 18th century, made references to another portrait of Carissimi, but that one is lost. Somehow Ms. Rose felt uneasy about the portrait on the manuscript, mostly because the inscription below it was scraped off and the name of Giacomo Carissimi written in. She also learned that the painter of the portrait, the Dutchman Wallerant Vaillant, had never been to Italy, while Carissimi never left it. All these doubts pushed Ms. Rose to investigate the portrait further. To make a long story short, in the end she found out that the portrait was not of Carissimi, but of one Alexander Morus (his last name sometimes is spelled as More). Morus, whose father was Scottish, was a Protestant preacher born in 1616 in Castres, France. He died in 1670 in Paris. Morus taught at a Huguenot college in Castres, then moved to Geneva where he became a professor of the Greek language, and later lived in Amsterdam, where he was a professor of theology at Amsterdam University. It was during those years that Vaillant painted his portrait, and this portrait was well known at the time. Why a scribe preparing a manuscript of Carissimi would use a wrong portrait is not clear. Here’s what Ms. Rose writes about this matter: “This scribe must have thought that his manuscript would look more impressive if it contained a portrait of the composer. Equally, he must have known that this portrait was not a portrait of the composer. Carissimi (I605-74) and More (1616-70) would have been near the same age at the time. But it was surely an act of boldness, to say the least, to take the portrait of a French Protestant theologian.”

decided to include his portrait, as we often do when we write about a composer or a performer, so we searched the web and came up with the portrait you see to theleft. It was used on many sites, some quite established, for example, France Musique, a French national public music channel. Then some time ago we received an email from one of our listeners, who told us that the portrait is not of Carissimi at all. That was surprising, so we decided to research the matter. Sure enough, almost immediately we came across an old article by the musicologist Gloria Rose called A Portrait Called Carissimi. In this article Rose wrote about the origins of the portrait: it could be found at the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris as the frontispiece to a manuscript containing numerous works by Carissimi. Moreover, this is the only surviving portrait of the composer: while Giuseppe Ottavio Pitoni, a composer and music theorist who lived in Rome in the first half of the 18th century, made references to another portrait of Carissimi, but that one is lost. Somehow Ms. Rose felt uneasy about the portrait on the manuscript, mostly because the inscription below it was scraped off and the name of Giacomo Carissimi written in. She also learned that the painter of the portrait, the Dutchman Wallerant Vaillant, had never been to Italy, while Carissimi never left it. All these doubts pushed Ms. Rose to investigate the portrait further. To make a long story short, in the end she found out that the portrait was not of Carissimi, but of one Alexander Morus (his last name sometimes is spelled as More). Morus, whose father was Scottish, was a Protestant preacher born in 1616 in Castres, France. He died in 1670 in Paris. Morus taught at a Huguenot college in Castres, then moved to Geneva where he became a professor of the Greek language, and later lived in Amsterdam, where he was a professor of theology at Amsterdam University. It was during those years that Vaillant painted his portrait, and this portrait was well known at the time. Why a scribe preparing a manuscript of Carissimi would use a wrong portrait is not clear. Here’s what Ms. Rose writes about this matter: “This scribe must have thought that his manuscript would look more impressive if it contained a portrait of the composer. Equally, he must have known that this portrait was not a portrait of the composer. Carissimi (I605-74) and More (1616-70) would have been near the same age at the time. But it was surely an act of boldness, to say the least, to take the portrait of a French Protestant theologian.”

A brief note on Gloria Rose. She was born in 1933, received her Ph.D. from Yale and taught at the University of Pittsburgh. Her research dealt with 17th-century Italian music, particularly Carissimi’s chamber cantata. She was married to Robert Donington, a British musicologist and a specialist in early music. Ms. Rose died in 1974, at just 40 years old.Permalink