Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

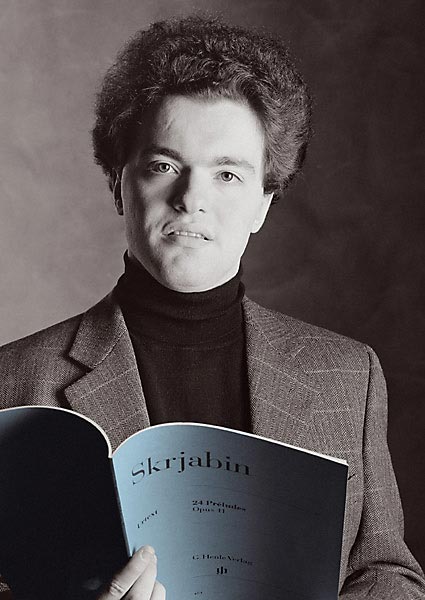

This Week in Classical Music: October 11, 2021. Evgeny Kissin. Evgeny Kissin, one of the greatest pianists of his generation, turned 50 yesterday. Kissin has been dazzling the public for almost 38 years, since the time when, at the age of 12, he gave a performance at the Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatory (performing at the Great Hall is the Russian equivalent of performing at the Stern Auditorium of the Carnegie Hall: an honor and acknowledgement of the performer’s talent). Kissin was born in Moscow on October 10th of 1971. At the age of six he went to the Gnessin music school, where his teacher was Anna Cantor. Cantor, who died on July 27th of this year, remained his only teacher. Kissin and Cantor were uniquely close; she traveled with him and lived her last years in his home in Prague. Recognized as a child prodigy in the Soviet Union, Kissin started his international career at the age of 14. In 1987 he first played in what was then West Berlin; a year later, to great acclaim, he played Tchaikovsky’s First piano concerto under the direction of Herbert von Karajan. In 1990 Kissin played his debut American concert in New York, performing both of Chopin’s piano concertos with the New York Philharmonic and Zubin Mehta. A week later he gave a recital at the Carnegie Hall. In 1997 he made history by playing the first ever piano recital at the Proms in the Royal Albert Hall. Kissin has played with all major orchestras, all major conductors; he also played chamber music with many leading musicians of the day. His concerts are always sold out.

almost 38 years, since the time when, at the age of 12, he gave a performance at the Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatory (performing at the Great Hall is the Russian equivalent of performing at the Stern Auditorium of the Carnegie Hall: an honor and acknowledgement of the performer’s talent). Kissin was born in Moscow on October 10th of 1971. At the age of six he went to the Gnessin music school, where his teacher was Anna Cantor. Cantor, who died on July 27th of this year, remained his only teacher. Kissin and Cantor were uniquely close; she traveled with him and lived her last years in his home in Prague. Recognized as a child prodigy in the Soviet Union, Kissin started his international career at the age of 14. In 1987 he first played in what was then West Berlin; a year later, to great acclaim, he played Tchaikovsky’s First piano concerto under the direction of Herbert von Karajan. In 1990 Kissin played his debut American concert in New York, performing both of Chopin’s piano concertos with the New York Philharmonic and Zubin Mehta. A week later he gave a recital at the Carnegie Hall. In 1997 he made history by playing the first ever piano recital at the Proms in the Royal Albert Hall. Kissin has played with all major orchestras, all major conductors; he also played chamber music with many leading musicians of the day. His concerts are always sold out.

Kissin’s playing combines phenomenal technique with interpretive depth. There is no affectation in his performances. His repertoire is broad, but he’s best know for his Romantics, from Chopin, Schubert and Schumann to Rachmaninov. Kissin also writes poetry and prose and does so in Russian and, surprisingly,, in Yiddish. After leaving Russia, Kissin, who has Russian, British and Israeli citizenships, has lived in New York, London, and Paris. He nowlives in Prague with his wife and three children from her previous marriage.

Kissin has a broad discography and is well represented on all streaming services. Here’s something of a rarity, Schubert’s Piano Sonata no. 17 in D major D. 850. This live recording was made in Verbier in 2014.Permalink

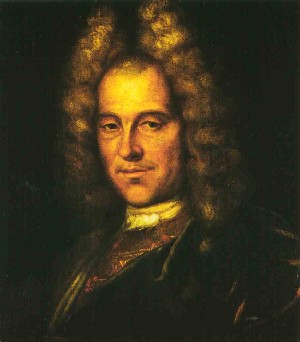

This Week in Classical Music: October 4, 2021. Johann Joseph Fux. The great German composer of the early baroque, Heinrich Schütz was born this week in Köstritz, a town in Thuringia, on October 8th of 1585 (we’ve written about him here and here). Also, Giuseppe Verdi was born on October 9th of 1813 and Camille Saint-Saëns, on the same day in 1835. Both are very popular (Verdi being a much bigger talent), and we’ve featured them many times. One composer who somehow escaped our attention is another German, Johann Joseph Fux. While Schütz was enormously influential as composer, Fux is more famous for his theoretical opus Gradus ad Parnassum (Steps to Mount Parnassus). It shouldn’t be confused with Carl Czerny’s Gradus ad Parnassum, a collection of study piano pieces familiar to most pianists. Fux’s Gradus is completely a different thing, and we’ll get to it in a minute.

Thuringia, on October 8th of 1585 (we’ve written about him here and here). Also, Giuseppe Verdi was born on October 9th of 1813 and Camille Saint-Saëns, on the same day in 1835. Both are very popular (Verdi being a much bigger talent), and we’ve featured them many times. One composer who somehow escaped our attention is another German, Johann Joseph Fux. While Schütz was enormously influential as composer, Fux is more famous for his theoretical opus Gradus ad Parnassum (Steps to Mount Parnassus). It shouldn’t be confused with Carl Czerny’s Gradus ad Parnassum, a collection of study piano pieces familiar to most pianists. Fux’s Gradus is completely a different thing, and we’ll get to it in a minute.

Fux was bon in 1660 (the exact date isn’t known) in a village outside of Graz, in Austrian Styria. He probably studied music in Graz, and later served as organist in Ingolstadt, Bavaria. It seems that around that time he visited Italy and was influenced by Arcangelo Corelli and Bernardo Pasquini. Fux moved to Vienna in 1690 and several years later was hired as the court composer to the Emperor Leopold I. Leopold was a music lover, a patron and composer himself: some of his music survives, for example, an ordinary mass titled Missa angeli custodis and the Requiem Mass for his first wife (here on YouTube). Love for music ran in Leopold’s Habsburg family: his father, Ferdinand III, Holy Roman Emperor, was also a music benefactor and composer; 100 years later, Joseph II would become Mozart’s patron. Leopold thought highly of Fux and in 1715 made him the Hofkapellmeister, the leader of Wiener Hofmusikkapelle, an ancient musical institution established in 1498; abolished in 1922, it was the predecessor of the Vienna Boys’ Choir. At the Hofmusikkapelle Fux was assisted by Antonio Caldara, a well-known Italian opera composer. When Leopold I died in 1705, his son Joseph became the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph I, and, upon Joseph’s death, the title went to Leopold’s other son, Charles, who ruled as Charles VI. Both continued to employ Fux, who lived in Vienna the rest of his life, dying in 1741. As the court composer, Fux was required to write masses and other church music; he also composed operas, oratorios and Tafelmusik (Table music), music for feasts and banquets. Here is Fux’s Overture in D major, No. 4, performed by the Freiburger Barockorchester.

Back to Gradus ad Parnassum: Fux wrote it in 1725, in Latin, but soon after it was translated into German, French and English. The first part of the book talks about intervals and their relations to number. But it’s the second half that made it famous: it presents the theoretical discussion of counterpoint, instructions on how to write sacred music and other musical techniques. It’s written in the form of a dialogue, with one person, the teacher, representing Palestrina, and another, the student, Fux himself. A copy of Gradus ad Parnassum was in Johan Sebastian Bach’s personal library. Haydn used it to teach himself counterpoint and later recommended it to his student, Beethoven. Mozart had an annotated copy. The book was used continuously from the day it was published and is still used and cited today. Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: September 27, 2021. Pianists and a Singer. October 1st is a big day for the pianists: Vladimir Horowitz was born on that day in 1903, and Vera Gornostayeva in 1939. Horowitz is world-famous, we’ve written about him on several occasions (for example, here), but still cannot quite come to terms with his art. Somehow, Horowitz managed to combine a sublime touch and bombast, the most incisive interpretation with showmanship, very often in the same recording. There are some pianists, like Arthur Rubinstein, who sound flawless to us, even if during their long careers they had changed the way they played some pieces (which Rubinstein, for one, certainly did). Horowitz is not like that: you listen to him and sometimes cringe: why so fast, why this blur, where’s the music? And the next moment everything is perfect, and you start thinking that maybe the mayhem he created several bars ago had some reason behind it. In any event, here’s Vladimir Horowitz playing Chopin’s Scherzo no. 1. This recording was most likely made in 1951. By the way, Chopin was only 21 when he wrote this Scherzo.

Gornostayeva in 1939. Horowitz is world-famous, we’ve written about him on several occasions (for example, here), but still cannot quite come to terms with his art. Somehow, Horowitz managed to combine a sublime touch and bombast, the most incisive interpretation with showmanship, very often in the same recording. There are some pianists, like Arthur Rubinstein, who sound flawless to us, even if during their long careers they had changed the way they played some pieces (which Rubinstein, for one, certainly did). Horowitz is not like that: you listen to him and sometimes cringe: why so fast, why this blur, where’s the music? And the next moment everything is perfect, and you start thinking that maybe the mayhem he created several bars ago had some reason behind it. In any event, here’s Vladimir Horowitz playing Chopin’s Scherzo no. 1. This recording was most likely made in 1951. By the way, Chopin was only 21 when he wrote this Scherzo.

In the same entry we referred to above, we mentioned Vera Gornostayeva, a fine Russian pianist and teacher. Here she plays, in recital, Chopin’s Waltz in C-Sharp Minor op.64, no.2. It’s very well played, even if there’s no Horowitz’s fire in it. We’re not sure about the date of the recording, it’s probably from the 1970s.

The French composer Paul Dukas was also born on October 1st, in 1865. He’s known for one composition only, his brilliant orchestral piece The Sorcerer's Apprentice. Dukas was born in Paris into a Jewish family. He started composing at the age of 14, went to the Paris Conservatory at 16. To his great disappointment, despite several attempts he failed to win the coveted Prix de Rome. Dukas was very critical of his own compositions and destroyed most of the scores. He was very influential as a music critic; he also extensively wrote about history, philosophy, and politics. Here’s one of Dukas surviving compositions, Variations, Interlude et Finale sur un thème de Rameau. It’s performed by the pianist Marco Rapetti.

Fritz Wunderlich is one of our all-time favorite singers. We just missed his birthday: he was born on September 26th of 1930. As a Lied tenor, he’s incomparable (you can listen to Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin or Schumann’s Dichterliebe in our library). He was also wonderful in Mozart’s operas. Here’s Il mio tesoro from Act 2 of Mozrt’s Don Giovanni. Herbert von Karajan leads the Vienna Philharmonic orchestra.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: September 20, 2021. Geography. This week is rich on anniversaries and exceptionally diverse on geography. Gustav Holst was born on September 21st of 1874 in Cheltenham, England. A thoroughly English composer, he got his German-sounding name from his German-Swedish ancestors on the paternal side: his great-grandfather, Matthias Holst, a minor composer, pianist and harpist, was born in Riga and served at the Imperial Russian Court in St. Petersburg. Gustav Holst was quite famous during his lifetime; these days outside of Britain he’s mostly known for his orchestral suite The Planets. Holst studied at the Royal College of Music under Charles Stanford. Another English composer, Ralph Vaughan Williams, was his close friend, and so was Arnold Bax. Holst was a wonderful teacher, among his students were composers Michael Tippett and Benjamin Britten. The Planets were composed between 1914 and 1917. Each of the “planet” movements is supposed to have an astrological meaning, which escapes us, and a certain mood, which can be heard much clearer. Here, for example, is the fourth movement of the suite: Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity. James Levine conducts the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

of 1874 in Cheltenham, England. A thoroughly English composer, he got his German-sounding name from his German-Swedish ancestors on the paternal side: his great-grandfather, Matthias Holst, a minor composer, pianist and harpist, was born in Riga and served at the Imperial Russian Court in St. Petersburg. Gustav Holst was quite famous during his lifetime; these days outside of Britain he’s mostly known for his orchestral suite The Planets. Holst studied at the Royal College of Music under Charles Stanford. Another English composer, Ralph Vaughan Williams, was his close friend, and so was Arnold Bax. Holst was a wonderful teacher, among his students were composers Michael Tippett and Benjamin Britten. The Planets were composed between 1914 and 1917. Each of the “planet” movements is supposed to have an astrological meaning, which escapes us, and a certain mood, which can be heard much clearer. Here, for example, is the fourth movement of the suite: Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity. James Levine conducts the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

Mikalojus Čiurlionis, a Lithuanian composer, painter and writer, was born on September 22nd of 1875. He’s one of the central cultural figures in modern Lithuanian history. Andrzej Panufnik, one of the most interesting Polish composers of the 20th century, was born on September 24th of 1914 in Warsaw. Here’s what we wrote about him to commemorate his 100th anniversary. Jean-Philippe Rameau, born on September 25th of 1683 in Dijon, was one of the greatest French composers of the Baroque, and probably of all of French music. Here’s the Overture to Rameau’s opera Dardanus, a tragédie en musique, as opera was then called in France. Dardanus premiered at the Paris Opéra on November 19th of 1739. Marc Minkowski leads Les Musiciens du Louvre.

So far we’ve visited England, Lithuania, Poland and France on our list of anniversaries. Three more countries are still ahead. Dmitry Shostakovich was born in imperial Russia, became one of the most famous composers of the Soviet Union and now is venerated as one of Russia’s greatest. Here’s one of our many entries on Shostakovich. Komitas was born in Turkey, in the town of Kütahya, on September 26th of 1869 and died in Paris, France on October 22nd of 1935, but he is an utterly Armenian composer and is celebrated in that country as Čiurlionis is in Lithuania or Shostakovich in Russia. He collected folksongs, as Bartok did in Hungary, and singlehandedly created a Western-style musical tradition in Armenia. And finally, an American: George Gershwin, named Jacob Gershowitz at birth, was born on September 26th of 1898 in Brooklyn, New York.

Seven composers, seven countries. Should we add a Canadian, Glenn Gould, born in Toronto on September 25th of 1932? Maybe next time.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: September 20, 2021. Geography. This week is rich on anniversaries and exceptionally diverse on geography. Gustav Holst was born on September 21st of 1874 in Cheltenham, England. A thoroughly English composer, he got his German-sounding name from his German-Swedish ancestors on the paternal side: his great-grandfather, Matthias Holst, a minor composer, pianist and harpist, was born in Riga and served at the Imperial Russian Court in St. Petersburg. Gustav Holst was quite famous during his lifetime; these days outside of Britain he’s mostly known for his orchestral suite The Planets. Holst studied at the Royal College of Music under Charles Stanford. Another English composer, Ralph Vaughan Williams, was his close friend, and so was Arnold Bax. Holst was a wonderful teacher, among his students were composers Michael Tippett and Benjamin Britten. The Planets were composed between 1914 and 1917. Each of the “planet” movements is supposed to have an astrological meaning, which escapes us, and a certain mood, which can be heard much clearer. Here, for example, is the fourth movement of the suite: Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity. James Levine conducts the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

of 1874 in Cheltenham, England. A thoroughly English composer, he got his German-sounding name from his German-Swedish ancestors on the paternal side: his great-grandfather, Matthias Holst, a minor composer, pianist and harpist, was born in Riga and served at the Imperial Russian Court in St. Petersburg. Gustav Holst was quite famous during his lifetime; these days outside of Britain he’s mostly known for his orchestral suite The Planets. Holst studied at the Royal College of Music under Charles Stanford. Another English composer, Ralph Vaughan Williams, was his close friend, and so was Arnold Bax. Holst was a wonderful teacher, among his students were composers Michael Tippett and Benjamin Britten. The Planets were composed between 1914 and 1917. Each of the “planet” movements is supposed to have an astrological meaning, which escapes us, and a certain mood, which can be heard much clearer. Here, for example, is the fourth movement of the suite: Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity. James Levine conducts the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

Mikalojus Čiurlionis, a Lithuanian composer, painter and writer, was born on September 22nd of 1875. He’s one of the central cultural figures in modern Lithuanian history. Andrzej Panufnik, one of the most interesting Polish composers of the 20th century, was born on September 24th of 1914 in Warsaw. Here’s what we wrote about him to commemorate his 100th anniversary. Jean-Philippe Rameau, born on September 25th of 1683 in Dijon, was one of the greatest French composers of the Baroque, and probably of all of French music. Here’s the Overture to Rameau’s opera Dardanus, a tragédie en musique, as opera was then called in France. Dardanus premiered at the Paris Opéra on November 19th of 1739. Marc Minkowski leads Les Musiciens du Louvre.

So far we’ve visited England, Lithuania, Poland and France on our list of anniversaries. Three more countries are still ahead. Dmitry Shostakovich was born in imperial Russia, became one of the most famous composers of the Soviet Union and now is venerated as one of Russia’s greatest. Here’s one of our many entries on Shostakovich. Komitas was born in Turkey, in the town of Kütahya, on September 26th of 1869 and died in Paris, France on October 22nd of 1935, but he is an utterly Armenian composer and is celebrated in that country as Čiurlionis is in Lithuania or Shostakovich in Russia. He collected folksongs, as Bartok did in Hungary, and singlehandedly created a Western-style musical tradition in Armenia. And finally, an American: George Gershwin, named Jacob Gershowitz at birth, was born on September 26th of 1898 in Brooklyn, New York.

Seven composers, seven countries. Should we add a Canadian, Glenn Gould, born in Toronto on September 25th of 1932? Maybe next time.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: September 13, 2021. The Little-Known Boismortier. Today our guest Aleah Fitzwater writes about the French composer Joseph Bodin de Boismortier. Before we get to this interesting but rather obscure Frenchman, we’d like to mention several composers and singers whose anniversaries are celebrated this week. Girolamo Frescobaldi, one of the first composers to write for a clavier instrument, was born on this day in 1583. Also on this day but in 1819 Clara Wieck was born. We know her better as Clara Schumann, Robert’s wife; she was a wonderful pianist and composer and an influential figure in German musical circles. And Arnold Schoenberg, a great modernist composer who pretty much changed the way we listen to music, was also born on September 13, in 1874. Luigi Cherubini, beloved by Beethoven and Rossini, was born September 14th of 1760. And the three singers, Jessye Norman, Elīna Garanča and Anna Netrebko were born on September 15th of 1945, September 16th of 1976 and September 18th of 1971, respectively. Norman and Netrebko don’t need an introduction (Netrebko will turn 50); Garanča is one of the best mezzos singing today. And now to Aleah and Boismortier:

Before we get to this interesting but rather obscure Frenchman, we’d like to mention several composers and singers whose anniversaries are celebrated this week. Girolamo Frescobaldi, one of the first composers to write for a clavier instrument, was born on this day in 1583. Also on this day but in 1819 Clara Wieck was born. We know her better as Clara Schumann, Robert’s wife; she was a wonderful pianist and composer and an influential figure in German musical circles. And Arnold Schoenberg, a great modernist composer who pretty much changed the way we listen to music, was also born on September 13, in 1874. Luigi Cherubini, beloved by Beethoven and Rossini, was born September 14th of 1760. And the three singers, Jessye Norman, Elīna Garanča and Anna Netrebko were born on September 15th of 1945, September 16th of 1976 and September 18th of 1971, respectively. Norman and Netrebko don’t need an introduction (Netrebko will turn 50); Garanča is one of the best mezzos singing today. And now to Aleah and Boismortier:

Joseph Bodin de Boismortier was born in Lorraine, France in 1689. He was a Baroque-era composer who excelled at the concerto form. According to Wikipedia, he was the first French composer to use the Italian concerto form. In his lifetime, he became famous and was known as “The French Telemann.”

The Rococo Era. Boismortier was a composer in the Rococo Era. Rococo translates as “Shell work.” This artistic era originated in France in the late 17th century, and eventually spread throughout Europe as a reaction against Louis XIV and the bright Baroque styles. The Rococo era is signified by its darker undertones, and emphasis on ornamentation and detail. Both painters and composers were affected by this new artistic movement.

Musical Education. When Boismortier’s family moved to Metz, France, he began to study with a motetist named Montigny. During his studies, he wrote several Airs. Boismortier’s early compositions such as his Airs went over extremely well in Paris. He was highly influenced by Italian forms, which made his music quite unique during this time. As his skills as a composer grew, his pieces became statelier and more beautiful.

Over 100 Pieces in 20 Years. From 1724 to 1747, Boismortier wrote and published over 100 different pieces. These ranged from full ballets to sonatas and concertos. It is also reported that he wrote a flute method book, but that it was lost. Let’s delve into some of his more popular pieces!

Opera-Ballets. Boismortier wrote two Ballets during his lifetime: Les Voyages de L’Amour, and Don Quichotte chez la Duchesse. According to Gramophone.com, Les Voyages de L’Amour tells the tale of Cupid searching for his love. Eventually, he meets a Shepherdess named Daphne. The instrumentation of Les Voyages includes a romantic yet bright combination of hurdy-gurdy, flute, cello and bassoon. The score is full of playful dances and Rigadoons and is certainly a feel-good ballet. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SsErw9kRbRQ (continue reading here).Permalink