Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

This Week in Classical Music: July 5, 2021. Mahler and Gedda. Gustav Mahler’s birthday is on July 7th. He was born in 1860 in Bohemia (then part of the Austria-Hungary, now the Czech Republic), into a poor German-speaking Jewish family. We’ve written about Mahler many times; his music was slow in acceptance, to a large extent because of its complexity and new nature, but also, in the 1930s and 1940s, for political and ethnic reasons. Mahler became extremely popular in the second half of the 20th century, but it seems that now, again, his music is fading somewhat. We think of it as a litmus test, this time more cultural than political. The changes are especially obvious in radio programming: there was a time when WFMT, a premier classical music station, would broadcasts his symphonies on a regular basis, and especially onhis birthday. Now you will only hear Mahler when WFMT runs special programs, such as old recorded concerts of the symphony orchestras or programs like Henry Fogel’s “Collectors’ Corner.” We don’t know the exact reasons for this – it’s difficult to imagine that WFMT just decided that people stopped loving Mahler’s music. We can only surmise that Mahler’s symphonies are too long and don’t allow for many commercial interruptions, that they are too complex (WFMT, like many other stations, has been trending toward simpler music for years), and that WFMT need more airtime for women composers. Of course, there may also be personal biases at play or other reasons we’re not aware of. But in the end, the results are obvious: Mahler’s music, if not directly banned, is relegated. This is unfortunate and, we hope, will be reversed in the future. In the meantime, here is the fourth movement, Adagio. Sehr langsam und noch zurückhaltend, from Mahler’s Symphony no. 9. Pierre Boulez conducts the Chicago Symphony.

Republic), into a poor German-speaking Jewish family. We’ve written about Mahler many times; his music was slow in acceptance, to a large extent because of its complexity and new nature, but also, in the 1930s and 1940s, for political and ethnic reasons. Mahler became extremely popular in the second half of the 20th century, but it seems that now, again, his music is fading somewhat. We think of it as a litmus test, this time more cultural than political. The changes are especially obvious in radio programming: there was a time when WFMT, a premier classical music station, would broadcasts his symphonies on a regular basis, and especially onhis birthday. Now you will only hear Mahler when WFMT runs special programs, such as old recorded concerts of the symphony orchestras or programs like Henry Fogel’s “Collectors’ Corner.” We don’t know the exact reasons for this – it’s difficult to imagine that WFMT just decided that people stopped loving Mahler’s music. We can only surmise that Mahler’s symphonies are too long and don’t allow for many commercial interruptions, that they are too complex (WFMT, like many other stations, has been trending toward simpler music for years), and that WFMT need more airtime for women composers. Of course, there may also be personal biases at play or other reasons we’re not aware of. But in the end, the results are obvious: Mahler’s music, if not directly banned, is relegated. This is unfortunate and, we hope, will be reversed in the future. In the meantime, here is the fourth movement, Adagio. Sehr langsam und noch zurückhaltend, from Mahler’s Symphony no. 9. Pierre Boulez conducts the Chicago Symphony.

Nicolai Gedda, born on July 11th of 1925 in Stockholm, was one of the best operatic tenors of the mid-20th century. Gedda had a rather unusual biography. He was born out of wedlock; his mother was a 17-year-old Swedish waitress, his father – an unemployed half-Russian, half-Swede. He was raised by his aunt on his father’s side, who was born in Riga, and her husband, Mikhail Ustinoff, a Russian Cossack (and a relative of the famous actor Peter Ustinov). Gedda’s biological parents lived in the same house, but he thought they were his aunt and uncle. Gedda grew up bilingual, speaking Swedish and Russian; he would later turn into a veritable polyglot, learning (and performing operas in) French, German, Italian, English, and Czech, in addition to his native Swedish and Russian. He studied singing in Stockholm with Carl Martin Oehman, a Swedish tenor and singing teacher, who “discovered” Jussi Björling. Gedda made his debut in the Royal Swedish Opera in 1951. Two years later he was already singing in La Scala (Don Ottavio in Mozart’s Don Giovanni). Through his meeting with Walter Legge, who was extremely impressed by Gedda’s singing, he got a recording contract with HMV (His Master’s Voice). In 1954, Gedda moved to Paris, where he sung at the Opéra and in many concerts and festivals. His Covent Garden debut followed the next year and, in 1957, he debuted at the Met, where he sung for 22 seasons. Gedda’s repertoire was remarkably broad: he sung Italian and Russian operas, the Frenchmen Gounod, Berlioz and Biset, he was great in Mozart and operas by the Soviet composers: Shostakovich’s Lady MacBeth of Mtsensk and Prokofiev’s War and Peace. He sung the role of Lohengrin and was a great proponent of the German Lied and Russian Orthodox songs. Gedda sung beautifully well into his 70s. Here is Nicolai Gedda brilliantly singing the aria Salut! Demeure chaste et pure from Gounod’s Faust in the 1978 recording. Andre Cluytens is conducting the Paris Opera orchestra.Permalink

tenors of the mid-20th century. Gedda had a rather unusual biography. He was born out of wedlock; his mother was a 17-year-old Swedish waitress, his father – an unemployed half-Russian, half-Swede. He was raised by his aunt on his father’s side, who was born in Riga, and her husband, Mikhail Ustinoff, a Russian Cossack (and a relative of the famous actor Peter Ustinov). Gedda’s biological parents lived in the same house, but he thought they were his aunt and uncle. Gedda grew up bilingual, speaking Swedish and Russian; he would later turn into a veritable polyglot, learning (and performing operas in) French, German, Italian, English, and Czech, in addition to his native Swedish and Russian. He studied singing in Stockholm with Carl Martin Oehman, a Swedish tenor and singing teacher, who “discovered” Jussi Björling. Gedda made his debut in the Royal Swedish Opera in 1951. Two years later he was already singing in La Scala (Don Ottavio in Mozart’s Don Giovanni). Through his meeting with Walter Legge, who was extremely impressed by Gedda’s singing, he got a recording contract with HMV (His Master’s Voice). In 1954, Gedda moved to Paris, where he sung at the Opéra and in many concerts and festivals. His Covent Garden debut followed the next year and, in 1957, he debuted at the Met, where he sung for 22 seasons. Gedda’s repertoire was remarkably broad: he sung Italian and Russian operas, the Frenchmen Gounod, Berlioz and Biset, he was great in Mozart and operas by the Soviet composers: Shostakovich’s Lady MacBeth of Mtsensk and Prokofiev’s War and Peace. He sung the role of Lohengrin and was a great proponent of the German Lied and Russian Orthodox songs. Gedda sung beautifully well into his 70s. Here is Nicolai Gedda brilliantly singing the aria Salut! Demeure chaste et pure from Gounod’s Faust in the 1978 recording. Andre Cluytens is conducting the Paris Opera orchestra.Permalink

- Which solo instrument?

- When was it written?

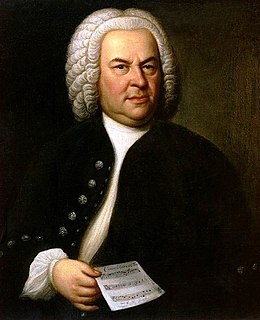

This Week in Classical Music: June 28, 2021. A Guest Entry: Bach Partita in E Minor for Solo Flute. Today we’re publishing an entry by a guest, Aleah Fitzwater, a studio flute teacher and music blogger who’s analyzing Bach’s Partita for Solo Flure. You can read more about Aleah at the bottom of this entry. She recommends several recordings of the partita; you can also listen to it here in the performance by James Galway.

and music blogger who’s analyzing Bach’s Partita for Solo Flure. You can read more about Aleah at the bottom of this entry. She recommends several recordings of the partita; you can also listen to it here in the performance by James Galway.

Bach Partita in E Minor for Solo Flute

The Bach Partita in E minor (BWV 1013) is one of those pieces that you could spend years with, and not quite perfect. It is the Moonlight Sonata of flute pieces.

One might expect this piece to be accompanied by basso continuo, but it was just written for a solo instrument. Naturally, the next questions I would answer are as follows:

After diving into a little research, I discovered just how many unanswered questions still follow this piece.

A Piece Shrouded in Mystery

One of the many things that I love about this partita is the uncertainty of it all. Nobody is sure exactly when it was written.

Some historians even propose that BWV 1013 was originally intended for violin, though it is usually performed on flute today. They think it may have been for violin, because the piece has no breath marks. There are long stretches of phrases that would simply sound odd if broken, which leads to many challenges for the flutist. Others argue that the piece was written for flute, but influenced by trends in the violin music of the time (JSOR.org). But without so much as a title from JS Bach, how would we ever know?

Discovery

The piece was first discovered by Karl Straube, a well-known church musician and organist. He was actually the one who named it, not Johann Sebastian Bach. I have to wonder- What would Bach have called it instead? Perhaps the piece was untitled because it was unfinished, which begs the question:

Should it be played with basso continuo after all?

There is only one manuscript from the original time period. It can be estimated that it was written after the 1720’s, because of the style. That being said, historians are also unsure of the transcriptionist who penned this copy.

Movements

Allemande

The arpeggiations of the first movement strongly implies a chordal structure. It gives us the sense that there are multiple flutes (or a harpsichord) beneath the louder melody up top. Though it is somewhat technically challenging, when the Allemande is played correctly, it gives us a laid-back feeling, as if a shepherd were playing in a meadow.

Courante

The Partita’s second movement starts off with a sunny yellow color. The accented feeling from the higher note of each measure gives it a near-sassy attitude.

Sarabande

The tone of this Sarabande is melancholy yet regal. The delicacy at which Jean-Pierre Rampal plays it at is most demanding. This movement is simply too easy to overdo. The player needs an entire reset both physically and emotionally, between the Courante and the Sarabande. The piano sections of this movement sound like the softest crying.

Bourrée Anglais

The Bourrée Anglais, or, English dance, closes this partita with an energetic exclamation mark. This is both the fastest and most technically challenging of the five movements. Light-footed double tonguing and nimble thirds are crucial to pulling off the closing of this piece.

Recordings

I highly recommend this recording by Jean-Pierre Rampal https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_YOMtofcJRg as well as this recording by Pahud https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-LMni-U7Fiw . While there are recordings on wooden flutes that better capture the time period in which it was written, Rampal and Pahud’s recordings contain an impeccable emotional and dynamic sensitivity. In addition, Matvey Demin’s recording of the piece especially shines through in its tasteful ornamentations https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W6vrx5lWzDU

About the Author: Aleah Fitzwater is a studio flute teacher, and music blogger for https://scan-score.com/en/ and https://aleahfitzwater.com/ . In her free time, she enjoys arranging rock songs for flute, and cooking French cuisine. Permalink

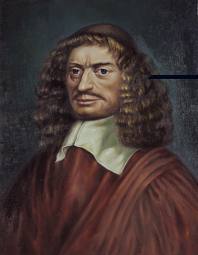

This Week in Classical Music: June 21, 2021. A Wrong Portrait. Some years ago we published an entry about an interesting early-Baroque Italian composer Giacomo Carissimi. We decided to include his portrait, as we often do when we write about a composer or a performer, so we searched the web and came up with the portrait you see to theleft. It was used on many sites, some quite established, for example, France Musique, a French national public music channel. Then some time ago we received an email from one of our listeners, who told us that the portrait is not of Carissimi at all. That was surprising, so we decided to research the matter. Sure enough, almost immediately we came across an old article by the musicologist Gloria Rose called A Portrait Called Carissimi. In this article Rose wrote about the origins of the portrait: it could be found at the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris as the frontispiece to a manuscript containing numerous works by Carissimi. Moreover, this is the only surviving portrait of the composer: while Giuseppe Ottavio Pitoni, a composer and music theorist who lived in Rome in the first half of the 18th century, made references to another portrait of Carissimi, but that one is lost. Somehow Ms. Rose felt uneasy about the portrait on the manuscript, mostly because the inscription below it was scraped off and the name of Giacomo Carissimi written in. She also learned that the painter of the portrait, the Dutchman Wallerant Vaillant, had never been to Italy, while Carissimi never left it. All these doubts pushed Ms. Rose to investigate the portrait further. To make a long story short, in the end she found out that the portrait was not of Carissimi, but of one Alexander Morus (his last name sometimes is spelled as More). Morus, whose father was Scottish, was a Protestant preacher born in 1616 in Castres, France. He died in 1670 in Paris. Morus taught at a Huguenot college in Castres, then moved to Geneva where he became a professor of the Greek language, and later lived in Amsterdam, where he was a professor of theology at Amsterdam University. It was during those years that Vaillant painted his portrait, and this portrait was well known at the time. Why a scribe preparing a manuscript of Carissimi would use a wrong portrait is not clear. Here’s what Ms. Rose writes about this matter: “This scribe must have thought that his manuscript would look more impressive if it contained a portrait of the composer. Equally, he must have known that this portrait was not a portrait of the composer. Carissimi (I605-74) and More (1616-70) would have been near the same age at the time. But it was surely an act of boldness, to say the least, to take the portrait of a French Protestant theologian.”

decided to include his portrait, as we often do when we write about a composer or a performer, so we searched the web and came up with the portrait you see to theleft. It was used on many sites, some quite established, for example, France Musique, a French national public music channel. Then some time ago we received an email from one of our listeners, who told us that the portrait is not of Carissimi at all. That was surprising, so we decided to research the matter. Sure enough, almost immediately we came across an old article by the musicologist Gloria Rose called A Portrait Called Carissimi. In this article Rose wrote about the origins of the portrait: it could be found at the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris as the frontispiece to a manuscript containing numerous works by Carissimi. Moreover, this is the only surviving portrait of the composer: while Giuseppe Ottavio Pitoni, a composer and music theorist who lived in Rome in the first half of the 18th century, made references to another portrait of Carissimi, but that one is lost. Somehow Ms. Rose felt uneasy about the portrait on the manuscript, mostly because the inscription below it was scraped off and the name of Giacomo Carissimi written in. She also learned that the painter of the portrait, the Dutchman Wallerant Vaillant, had never been to Italy, while Carissimi never left it. All these doubts pushed Ms. Rose to investigate the portrait further. To make a long story short, in the end she found out that the portrait was not of Carissimi, but of one Alexander Morus (his last name sometimes is spelled as More). Morus, whose father was Scottish, was a Protestant preacher born in 1616 in Castres, France. He died in 1670 in Paris. Morus taught at a Huguenot college in Castres, then moved to Geneva where he became a professor of the Greek language, and later lived in Amsterdam, where he was a professor of theology at Amsterdam University. It was during those years that Vaillant painted his portrait, and this portrait was well known at the time. Why a scribe preparing a manuscript of Carissimi would use a wrong portrait is not clear. Here’s what Ms. Rose writes about this matter: “This scribe must have thought that his manuscript would look more impressive if it contained a portrait of the composer. Equally, he must have known that this portrait was not a portrait of the composer. Carissimi (I605-74) and More (1616-70) would have been near the same age at the time. But it was surely an act of boldness, to say the least, to take the portrait of a French Protestant theologian.”

A brief note on Gloria Rose. She was born in 1933, received her Ph.D. from Yale and taught at the University of Pittsburgh. Her research dealt with 17th-century Italian music, particularly Carissimi’s chamber cantata. She was married to Robert Donington, a British musicologist and a specialist in early music. Ms. Rose died in 1974, at just 40 years old.Permalink

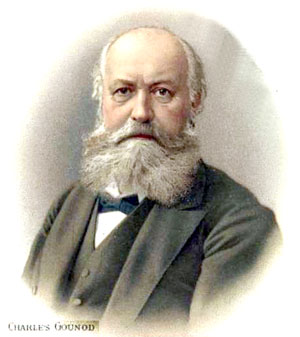

This Week in Classical Music: June 14, 2021. Short takes 2. We’re on a brief hiatus so this is going to be very short. On the 17th, there are two anniversaries, that of the French composer Charles Gounod, who was born in 1818, and that of Igor Stravinsky, one of the greatest composers of the 20th century. Edvard Grieg was born on June 15th of 1843. We feel bad that practically every year we somehow evade his birthday, having written just two partial entries about him thru all these years, putting him on par with Jacques Offenbach, who was also born this week, on June 20th of 1819. Clearly, Grieg deserves better. Maybe in two years, when he turns 180…

Charles Gounod, who was born in 1818, and that of Igor Stravinsky, one of the greatest composers of the 20th century. Edvard Grieg was born on June 15th of 1843. We feel bad that practically every year we somehow evade his birthday, having written just two partial entries about him thru all these years, putting him on par with Jacques Offenbach, who was also born this week, on June 20th of 1819. Clearly, Grieg deserves better. Maybe in two years, when he turns 180…

We promise a much more interesting entry next week, part of which will be dedicated to a misattributed portrait of a pretty famous Italian composer – misattributed not just by us but by several major musical sources. Also, we’ll write about a book on the state of classical music in our turbulent times: diverse opinions featured together, distinct approaches, and very different value systems, all in one volume. The cultural revolution is still marching on, if possibly at a slower pace, so we must keep up with it. Cheers and till next week.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: June 7, 2021. Short takes. Robert Schumann’s anniversary is tomorrow: he was born on June 8th of 1810 in Zwickau. He is one of the greatest composers of the 19th century, and we’ve dedicated many entries to his life and art, including longer articles on his song cycle Dichterliebe (here and here). Schumann’s songs are among the most beautiful and sophisticated examples of the lieder genre; only Schubert wrote songs on such a level. Still, not to diminish other forms that Schumann worked in, including his symphonies, concertos and chamber pieces, we probably love Schumann’s piano music the best. A set of eight piano pieces, Novelletten, op. 21, were written early in 1838. It was a difficult period in Schumann’s life: in November of 1837 he experienced a severe bout of depression and started drinking heavily. Both were possibly provoked by his future father-in-law, Friedrich Wieck, who would not consent to Robert’s marriage to his daughter, Clara. By January Schumann had recovered from the depression (and drinking) and entered a wildly creative period which lasted for four months, during which, in addition to Novelletten, he composed Kinderscenen op.15 and Kreisleriana op.16. He also started working on a string quartet, which he eventually abandoned (after studying the quartets by Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven he returned to this genre in 1842 and wrote three quartets op. 41). As for the Novelletten, you can listen to them here in the 1969 performance by the fine French pianist Jean-Bernard Pommier.

the 19th century, and we’ve dedicated many entries to his life and art, including longer articles on his song cycle Dichterliebe (here and here). Schumann’s songs are among the most beautiful and sophisticated examples of the lieder genre; only Schubert wrote songs on such a level. Still, not to diminish other forms that Schumann worked in, including his symphonies, concertos and chamber pieces, we probably love Schumann’s piano music the best. A set of eight piano pieces, Novelletten, op. 21, were written early in 1838. It was a difficult period in Schumann’s life: in November of 1837 he experienced a severe bout of depression and started drinking heavily. Both were possibly provoked by his future father-in-law, Friedrich Wieck, who would not consent to Robert’s marriage to his daughter, Clara. By January Schumann had recovered from the depression (and drinking) and entered a wildly creative period which lasted for four months, during which, in addition to Novelletten, he composed Kinderscenen op.15 and Kreisleriana op.16. He also started working on a string quartet, which he eventually abandoned (after studying the quartets by Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven he returned to this genre in 1842 and wrote three quartets op. 41). As for the Novelletten, you can listen to them here in the 1969 performance by the fine French pianist Jean-Bernard Pommier.

A big anniversary, and also on June 8th: Tomaso Albinoni was born 350 years ago. A composer of modest gifts but large output, he wrote some pleasant music, now mostly forgotten. In contrast, very little of what Charles Wuorinen had written could be called “pleasant” but much of it is very interesting. This American modernist composer was born this week, on June 9th of 1938. Last year we dedicated an entry to him, you can read it here.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: May 31, 2021. Argerich and Tennstedt. It is hard to imagine, but Martha Argerich, that young girl who famously won the Chopin competition in Warsaw, will turn 80 on June 5th. We dedicated an entry to her a year ago, you can read it here. Ms. Argerich is still performing, or at least is scheduled to perform: many of her concerts have been cancelled, whether due to the Covid epidemic or for personal reasons (that’s not new, though: she’s been known for cancellations throughout her entire career). We wish her the very best and good health in particular, and to the millions of her admirers we wish for them to hear her play live.

turn 80 on June 5th. We dedicated an entry to her a year ago, you can read it here. Ms. Argerich is still performing, or at least is scheduled to perform: many of her concerts have been cancelled, whether due to the Covid epidemic or for personal reasons (that’s not new, though: she’s been known for cancellations throughout her entire career). We wish her the very best and good health in particular, and to the millions of her admirers we wish for them to hear her play live.

Here are some composers that were born this week: Marin Marais, on May 31, 1656, in Paris. The French composer and viol player, he studied the viol with the famous Sainte-Colombe and composition with Lully. Marais performed at the court of Louis XIV and was famous in France and beyond. Even though he’s mostly known for his viol compositions, Marais also wrote several operas. Here’s the Overture to his opera Alcione, performed by Le Concert des Nations under the direction of Jordi Savall. Georg Muffat (born on June 1st of 1673, about whom the Gove Dictionary writes: ”German composer and organist of French birth… He considered himself a German, although his ancestors were Scottish and his family had settled in Savoy in the early 17th century.” Also: Mikhail Glinka, the first Russian composer to reject the Italianate ways of his predecessors (June 1st of 1804); Sir Edward Elgar; and Aram Khachaturian, one of the better Soviet composers.

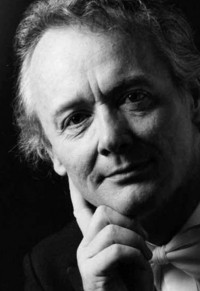

Two conductors also have their anniversaries this week: Evgeny Mravinsky, about whom we wrote here, and Klaus Tennstedt, a German conductor who was one of the 20th century’s greatest interpreters of Mahler’s symphonies. Tennstedt was born in Merseburg, near Leipzig, on June 6th of 1926. He studied the violin and piano in Leipzig Hochschule für Musik. He turned to conducting in 1948, after experiencing problems with the fingers on his left hand. Tennstedt held conducting positions in the German Democratic Republic but defected to Sweden in 1971. He made what the critics called a “stunning” debut with the Toronto Symphony in 1974, and then equally successfully performed with the Boston and Chicago Symphony orchestras. Tennstedt conducted all major American and European orchestras but was most closely associated with the London Philharmonic, where he was first the Principal Guest conductor and later Music Director. Tennstedt’s physical and emotional health came under pressure in later 1980s. He had two hip replacements and battled throat cancer, cancelled many of his concerts. In 1987 he collapsed during a rehearsal with the London Philharmonic and resigned his post immediately thereafter. He remained the orchestra’s Conductor Laurate and performed with them occasionally till 1994. Tennstedt died on January 11th of 1998 in Kiel, Germany. Here’s the last, sixth, movement of Mahler’s Symphony no. 3, which Mahler had marked Langsam. Ruhevoll. Empfunden (Slowly, tranquil, deeply felt). It is, all these things, as you can hear; Klaus Tennstedt leads the London Philharmonic Orchestra in the 1986 recording.Permalink

wrote here, and Klaus Tennstedt, a German conductor who was one of the 20th century’s greatest interpreters of Mahler’s symphonies. Tennstedt was born in Merseburg, near Leipzig, on June 6th of 1926. He studied the violin and piano in Leipzig Hochschule für Musik. He turned to conducting in 1948, after experiencing problems with the fingers on his left hand. Tennstedt held conducting positions in the German Democratic Republic but defected to Sweden in 1971. He made what the critics called a “stunning” debut with the Toronto Symphony in 1974, and then equally successfully performed with the Boston and Chicago Symphony orchestras. Tennstedt conducted all major American and European orchestras but was most closely associated with the London Philharmonic, where he was first the Principal Guest conductor and later Music Director. Tennstedt’s physical and emotional health came under pressure in later 1980s. He had two hip replacements and battled throat cancer, cancelled many of his concerts. In 1987 he collapsed during a rehearsal with the London Philharmonic and resigned his post immediately thereafter. He remained the orchestra’s Conductor Laurate and performed with them occasionally till 1994. Tennstedt died on January 11th of 1998 in Kiel, Germany. Here’s the last, sixth, movement of Mahler’s Symphony no. 3, which Mahler had marked Langsam. Ruhevoll. Empfunden (Slowly, tranquil, deeply felt). It is, all these things, as you can hear; Klaus Tennstedt leads the London Philharmonic Orchestra in the 1986 recording.Permalink