Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

This Week in Classical Music: November 4, 2019. Three pianists. Three very different pianists were born this week, György Cziffra, Walter Gieseking and Ivan Moravec. Walter Gieseking, the oldest of the three, was born on November 5th of 1895 in Lyon, France into the family of a distinguished German doctor. Gieseking spent his youth mostly in France and Italy; he started studying piano at the age of four but didn’t have a formal musical education till 16 when he entered the Hanover Conservatory. In 1920 he performed a nearly complete cycle of Beethoven’s sonatas. It was around that time that his affinity for the music of Debussy and Ravel became evident. Gieseking stayed in Germany during WWII and performed for the Nazi cultural organizations. Accused of collaboration, he wasn’t cleared till 1947, but even later he continued to be boycotted by Jewish organizations. He returned to the United States only in 1955 and played an all-Debussy program at the Carnegie Hall to great acclaim. Gieseking had a phenomenal memory, often memorizing music from a score. His repertory was very broad: he recorded all of Mozart’s and Ravel’s solo piano music, and practically all the solo works of Debussy. His recording of all Beethoven’s pianos sonatas was left incomplete because of his sudden death. Gieseking also often played contemporary music. But it was his Ravel and Debussy that stand out unsurpassed. Here’s Image, Book II, recorded in 1953.

Gieseking, the oldest of the three, was born on November 5th of 1895 in Lyon, France into the family of a distinguished German doctor. Gieseking spent his youth mostly in France and Italy; he started studying piano at the age of four but didn’t have a formal musical education till 16 when he entered the Hanover Conservatory. In 1920 he performed a nearly complete cycle of Beethoven’s sonatas. It was around that time that his affinity for the music of Debussy and Ravel became evident. Gieseking stayed in Germany during WWII and performed for the Nazi cultural organizations. Accused of collaboration, he wasn’t cleared till 1947, but even later he continued to be boycotted by Jewish organizations. He returned to the United States only in 1955 and played an all-Debussy program at the Carnegie Hall to great acclaim. Gieseking had a phenomenal memory, often memorizing music from a score. His repertory was very broad: he recorded all of Mozart’s and Ravel’s solo piano music, and practically all the solo works of Debussy. His recording of all Beethoven’s pianos sonatas was left incomplete because of his sudden death. Gieseking also often played contemporary music. But it was his Ravel and Debussy that stand out unsurpassed. Here’s Image, Book II, recorded in 1953.

György Cziffra’s life was as unusual as it gets, especially for a famous concert pianist. He was born on November 5th of 1921 in Budapest into a poor family of Hungarian gypsies. As a child, he earned money improvising on popular melodies at a local circus. In 1930 he entered the Liszt Academy in Budapest where he studied with Ernst von Dohnányi. Between 1933 and 1941, Cziffra successfully concertized in Hungary and other countries. In 1941 he was conscripted, sent to the Eastern front and soon after captured by Russian partisans; he spent the remaining war years as a prisoner. After the war he earned his living playing in bars. In 1950 he attempted to defect from Socialist Hungary, was captured and imprisoned again, this time for three years of hard-labor camp. He made several recordings after being released. Cziffra managed to escape in 1956, the year of the Hungarian Revolution, going first to Vienna and then settling in Paris. From that point on, till 1981, Cziffra’s career flourished. He was recognized as a supreme virtuoso, even though his many critics questioned some musical aspects of his performances. In 1981 yet another tragedy struck: his 37-year-old son died in a fire in his Paris apartment. Cziffra, heartbroken, never performed again. He died in Paris 13 year later, on January 17th of 1994. Here’s his recording of Balakirev’s “Oriental Fantasy” Islamey. It was made in 1954-1956 while Cziffra was still living in Hungary.

The somewhat under-appreciated Czech pianist Ivan Moravec was born on Nov 9th of 1930 in Prague. He studied in Prague, and later took classes with Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli. A citizen of an Eastern-Bloc country, he couldn’t travel to the West and was practically unknown to the European and American public. Eventually, though, his audio recordings made their way to the US and he was invited to make several recordings and to perform. The 1964 concerts with George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra launched his international concert career, but even after that the Czech authorities weren’t eager to let him travel. As a result, Western listeners heard relatively little of Moravec at the peak of his career. He lived in Prague for his whole life and died there on July 27th of 2015. He was one of the best interpreters of the music of Chopin; here is Chopin’s Nocturne op.9, no.2; this recording was made in 1965.Permalink

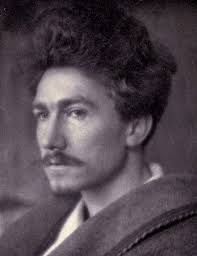

This Week in Classical Music: October 28, 2019. Opera Composers. Vincenzo Bellini, one of the greatest composers of the bel canto opera, was born on November 3rd of 1801 in Catania. The creator of such masterpieces as Norma, I Puritani, La sonnambula, he died at the age of 33. We’ve written about him on a number of occasions, and just this past week we mentioned that Giuditta Pasta premiered two of his operas, singing Amina in La sonnambula and the title role in Norma. But Bellini wasn’t the only opera composer to be born this week: quite an unexpected name shows up on the calendar, that of Ezra Pound. Yes, that very Ezra Pound, one of the finest poets of the 20th century, and, politically, a very controversial figure. He was born onOctober 30th of 1885 in Hailey, ID, but spent much of his life in Europe. Pound, who had no musical education, was a big lover of classical music. In his youth, he wrote musical criticism for several publications; one of his articles was about a concert given by the violinist Olga Rudge; they became friends and eventually lovers. They stayed together for the rest of Pound’s life (Rudge outlived him by 24 years – she died at the age of 100). Pound and Rudge (and also the Italian composer Alfredo Casella) were key figures in the Vivaldi revival, discovering manuscripts in the Turin library: it’s hard to imagine but in the early 20th century Vivaldi’s works were practically unknown to the general public. In the early 1920s, while living in Paris, Pound became friends with the American composer George Antheil. Pound was very interested in the music of troubadours, composers and performers from the medieval Occitan, – he felt that their art represented the ideal union of music and word. The poetry of troubadours influenced his own, especially his Cantos. Then, in 1923, he decided to write an opera which he called The Testament of François Villon, after a poem by the famous French 15th century poet. As Pound had no formal knowledge of compositional technique, he asked Antheil to consult him (on the front page of the score Pound mentioned Antheil as an “editor”). The Testament is an unusual creation, not quite an opera but a curious piece of music with a very unorthodox rythm (here are the first five minutes of it, performed by the ASKO-Ensemble under the direction of Reinbert de Leeuw, recorded at the Holland Festival in 1980). The Testament was performed in concert in 1926 and was praised by Virgil Thompson, the American composer of another unusual opera, Four Saints in Three Acts, on the libretto by Gertrude Stein. In 1932 Pound wrote his second opera, Cavalcanti, based on the life of the famous Italian poet and troubadour Guido Cavalcanti, whose poems influenced his friend Dante. That was his last known musical effort.

name shows up on the calendar, that of Ezra Pound. Yes, that very Ezra Pound, one of the finest poets of the 20th century, and, politically, a very controversial figure. He was born onOctober 30th of 1885 in Hailey, ID, but spent much of his life in Europe. Pound, who had no musical education, was a big lover of classical music. In his youth, he wrote musical criticism for several publications; one of his articles was about a concert given by the violinist Olga Rudge; they became friends and eventually lovers. They stayed together for the rest of Pound’s life (Rudge outlived him by 24 years – she died at the age of 100). Pound and Rudge (and also the Italian composer Alfredo Casella) were key figures in the Vivaldi revival, discovering manuscripts in the Turin library: it’s hard to imagine but in the early 20th century Vivaldi’s works were practically unknown to the general public. In the early 1920s, while living in Paris, Pound became friends with the American composer George Antheil. Pound was very interested in the music of troubadours, composers and performers from the medieval Occitan, – he felt that their art represented the ideal union of music and word. The poetry of troubadours influenced his own, especially his Cantos. Then, in 1923, he decided to write an opera which he called The Testament of François Villon, after a poem by the famous French 15th century poet. As Pound had no formal knowledge of compositional technique, he asked Antheil to consult him (on the front page of the score Pound mentioned Antheil as an “editor”). The Testament is an unusual creation, not quite an opera but a curious piece of music with a very unorthodox rythm (here are the first five minutes of it, performed by the ASKO-Ensemble under the direction of Reinbert de Leeuw, recorded at the Holland Festival in 1980). The Testament was performed in concert in 1926 and was praised by Virgil Thompson, the American composer of another unusual opera, Four Saints in Three Acts, on the libretto by Gertrude Stein. In 1932 Pound wrote his second opera, Cavalcanti, based on the life of the famous Italian poet and troubadour Guido Cavalcanti, whose poems influenced his friend Dante. That was his last known musical effort.

Two prominent conductors, the German Eugen Jochum and the Italian Giuseppe Sinopoli were also born this week, Jochum on November 1st of 1902, Sinopoli – on November 2nd of 1946. Permalink

The singer we mentioned above is Giuditta Pasta, born on October 26th of 1797. She had an unusually beautiful voice with a huge range, the voice Italians call soprano sfogato. What is more, several opera roles, central to the bel canto repertoire, were written specifically for her. Giuditta Pasta was born Giuditta Negri on November 26th of 1797 in Saronno near Milan (in 1816 she married one Giuseppe Pasta, a fellow singer, and took his name). She studied in Milan and sung her debut role at the age of 19. By her early 20s she had performed in all major opera theater of Italy. Her first great triumph was the role of Desdemona in Rossini’s Otello which she sung at the Théâtre Italien in 1821 in Paris. In the subsequent years she became acclaimed as the greatest soprano in Europe. Rossini wrote the role of Corinna in Il viaggio a Reims for her in 1825; Donizetti – the role of the protagonist in the opera Anna Bolena in 1830. Bellini wrote two roles for Pasta, that of Amina in La sonnambula and then the great role of Norma, both in 1831. In 1835 Pasta retired from stage – she was only 38 years old. Her voice, soprano sfogato, had an enormous range: naturally a mezzo it went up to the coloratura soprano range. Wikipedia gives a wonderful quote from Stendhal, who describes Giuditta Pasta’s voice this way: “… she possesses the rare ability to be able to sing contralto as easily as she can sing soprano. Many notes … have the ability to produce a kind of resonant and magnetic vibration, which, through some still unexplained combination of physical phenomena, exercises an instantaneous and hypnotic effect upon the soul of the spectator.” Giuditta Pasta died in Como, Italy, on April 1st of 1865.

The singer we mentioned above is Giuditta Pasta, born on October 26th of 1797. She had an unusually beautiful voice with a huge range, the voice Italians call soprano sfogato. What is more, several opera roles, central to the bel canto repertoire, were written specifically for her. Giuditta Pasta was born Giuditta Negri on November 26th of 1797 in Saronno near Milan (in 1816 she married one Giuseppe Pasta, a fellow singer, and took his name). She studied in Milan and sung her debut role at the age of 19. By her early 20s she had performed in all major opera theater of Italy. Her first great triumph was the role of Desdemona in Rossini’s Otello which she sung at the Théâtre Italien in 1821 in Paris. In the subsequent years she became acclaimed as the greatest soprano in Europe. Rossini wrote the role of Corinna in Il viaggio a Reims for her in 1825; Donizetti – the role of the protagonist in the opera Anna Bolena in 1830. Bellini wrote two roles for Pasta, that of Amina in La sonnambula and then the great role of Norma, both in 1831. In 1835 Pasta retired from stage – she was only 38 years old. Her voice, soprano sfogato, had an enormous range: naturally a mezzo it went up to the coloratura soprano range. Wikipedia gives a wonderful quote from Stendhal, who describes Giuditta Pasta’s voice this way: “… she possesses the rare ability to be able to sing contralto as easily as she can sing soprano. Many notes … have the ability to produce a kind of resonant and magnetic vibration, which, through some still unexplained combination of physical phenomena, exercises an instantaneous and hypnotic effect upon the soul of the spectator.” Giuditta Pasta died in Como, Italy, on April 1st of 1865.

October 21, 2019. Giuditta Pasta. There are several anniversaries which we’d like to commemorate today: the birthdays of Franz Liszt, Luciano Berio, George Biset and Domenico Scarlatti. And there is also a very special singer we’d also like to write about as well. Franz Liszt was born on October 22nd of 1811 in the Kingdom of Hungary, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. One of the most important composers of the 19th century, he was also the first (and the greatest) in a long line of piano virtuosos. We’ve written about his life and, separately, about his piano cycle Années de pèlerinage (for example, here and here). Please browse our library, which has an extensive collection of his works. Some of Liszt’s best works were written for the then newly-improved keyboard instrument, the piano, and so were most of Domenico Scarlatti’s numerous sonatas, though during his lifetime the main keyboard instrument was not the piano but the harpsichord. Domenico, the son of the great composer Alessandro Scarlatti, was born on October 26th of 1685 in Naples. Like Liszt, he was an excellent keyboard player, he even beat Handel in a 1709 harpsichord competition organized by Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni (Handel was judged to be a better organ player). Scarlatti wrote 555 sonatas; though we don’t have all of them, you could find several wonderful performances on our site. Another Italian, Luciano Berio, was born on October 24th of 1925 in Oneglia, Liguria, not far from the French border. One of the most interesting composers of the late 20th century, he had an unusual distinction of being uncompromisingly experimental and very popular at the same time. Here’s Berio’s O King, dedicated to Martin Luther King. Soprano Elise Ross is accompanied by members of the London Symphonietta, with the composer conducting. Finally, Georges Bizet, the author of Carmen, was born on October 25th of 1838 in Paris.

The portrait, above, was made by the Italian painter Giuseppe Molteni in 1829. Its title is “Portrait of the Singer Giuditta Pasta in the Stage Costume of “Nina or the Girl Driven Mad by Love”.” “Nina” is an opera by Giovanni Paisiello.Permalink

October 14, 2019. Karl Richter. A noted German composer Alexander von Zemlinsky was born on October 14th of 1871. Here’s our entry from six years ago. We think that the brief aside at the end of it, about the painter who created Zemlinky’s portrait, is quite fascinating and characteristic of the pre-Great War Viennese society. Luca Marenzio, the Italian composer of the late Renaissance active in Rome and Ferrara, was born on October 18th of 1553. Here’s a madrigal Solo et pensoso i più deserti campi, a setting of Petrarch’s poem, by Marenzio. It’s performed by the ensemble La Venexiana, Claudio Cavina conducting. And here is our previous entry on this wonderful composer. Also, the great Soviet pianist Emil Gilels was born on October 19th of 1916. Here is his 1972 recordings of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 21 in C major, Op. 53, Waldstein. Read more about Gilels here.

October 7, 2019. Verdi and Pavarotti. Giuseppe Verdi was born this week (on October 10th of 1813) and so was Luciano Pavarotti, a great interpreter of his music. We’ve written about Verdi before (for example, here and here) but never about Pavarotti. Luciano Pavarotti was born on October 12th of 1935 in Modena, Italy into a poor family: his father, Fernando, was a baker and his mother a cigar factory worker. Fernando was an amateur tenor (and, according to Luciano, a good one). From an early age Luciano was listening to his father’s recordings of the great Italian tenors: Beniamino Gigli, Tito Schipa, Enrico Caruso, and later those of his hero, Giuseppe Di Stefano. Luciano studied singing in Modena, where one of his teachers, Ettore Campogalliani, also taught his childhood friend, Mirella Freni (Campogalliani also worked with Renata Tebaldi, Renata Scotto, Ruggero Raimondi and Carlo Bergonzi). Rumor has it that Pavarotti never learned to read music. Pavarotti made his debut in 1961 in Reggio Emilia, singing the role of Rodolfo in La bohème. In the next two years he sung in Yugoslavia, Vienna, Moscow and London. While well-received, he wasn’t acclaimed as a future superstar. His break came when Joan Sutherland asked him to join her on an Australian tour, the main reason being that he was tall enough to stand next to her (she was 6’2’’). The grateful Pavarotti later said that he learned the breathing technique from Sutherland during that tour. Pavarotti made his La Scala debut in 1965 in La bohème; Mirella Freni sung the role of Mimi. In 1966 he sung Tonio in Donizetti's La fille du regiment at the Covent Garden, that was when music critics started calling him "King of the High Cs." In 1967 he made his Metropolitan opera debut, again as Rodolfo against’ Freni’s Mimi. With Joan Sutherland he sung on stage and made numerous recordings; some of these recording became legendary. By the early 1980s Pavarotti’s fame hit its zenith. He sung at the Metropolitan (altogether, he performed in 357 Met opera productions) and at all the major opera houses. (He was banned from the Lyric Opera of Chicago, though, for cancelling 26 of his planned 41 appearances). With Placido Domingo and Jose Carreras he created the “Three Tenors” act which became immensely popular, with the public usually not very interested in opera buying millions of records. Pavarotti maintained his voice for a very long time, though not always on the same level. His last performance at the Met was in March of 2004, when he was 68; he sung the role of Mario Cavaradossi in Puccini’s Tosca and received a standing ovation. In July of 2006 Pavarotti was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. He died in Modena on September 6th of 2007.

before (for example, here and here) but never about Pavarotti. Luciano Pavarotti was born on October 12th of 1935 in Modena, Italy into a poor family: his father, Fernando, was a baker and his mother a cigar factory worker. Fernando was an amateur tenor (and, according to Luciano, a good one). From an early age Luciano was listening to his father’s recordings of the great Italian tenors: Beniamino Gigli, Tito Schipa, Enrico Caruso, and later those of his hero, Giuseppe Di Stefano. Luciano studied singing in Modena, where one of his teachers, Ettore Campogalliani, also taught his childhood friend, Mirella Freni (Campogalliani also worked with Renata Tebaldi, Renata Scotto, Ruggero Raimondi and Carlo Bergonzi). Rumor has it that Pavarotti never learned to read music. Pavarotti made his debut in 1961 in Reggio Emilia, singing the role of Rodolfo in La bohème. In the next two years he sung in Yugoslavia, Vienna, Moscow and London. While well-received, he wasn’t acclaimed as a future superstar. His break came when Joan Sutherland asked him to join her on an Australian tour, the main reason being that he was tall enough to stand next to her (she was 6’2’’). The grateful Pavarotti later said that he learned the breathing technique from Sutherland during that tour. Pavarotti made his La Scala debut in 1965 in La bohème; Mirella Freni sung the role of Mimi. In 1966 he sung Tonio in Donizetti's La fille du regiment at the Covent Garden, that was when music critics started calling him "King of the High Cs." In 1967 he made his Metropolitan opera debut, again as Rodolfo against’ Freni’s Mimi. With Joan Sutherland he sung on stage and made numerous recordings; some of these recording became legendary. By the early 1980s Pavarotti’s fame hit its zenith. He sung at the Metropolitan (altogether, he performed in 357 Met opera productions) and at all the major opera houses. (He was banned from the Lyric Opera of Chicago, though, for cancelling 26 of his planned 41 appearances). With Placido Domingo and Jose Carreras he created the “Three Tenors” act which became immensely popular, with the public usually not very interested in opera buying millions of records. Pavarotti maintained his voice for a very long time, though not always on the same level. His last performance at the Met was in March of 2004, when he was 68; he sung the role of Mario Cavaradossi in Puccini’s Tosca and received a standing ovation. In July of 2006 Pavarotti was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. He died in Modena on September 6th of 2007.

Pavarotti, a lyrical tenor, had a bright and open voice of exceptional beauty which floated, seemingly effortlessly, above a full orchestra. In his New York Times obituary, the chief music critic Bernard Holland wrote: “… he possessed a sound remarkable for its ability to penetrate large spaces easily. Yet he was able to encase that powerful sound in elegant, brilliant colors. His recordings of the Donizetti repertory are still models of natural grace and pristine sound. The clear Italian diction and his understanding of the emotional power of words in music were exemplary.” Pavarotti was especially good in the bel canto repertory and in the Puccini operas, but several of his Verdi roles were outstanding. Here he is in the 1983 Metropolitan production of Verdi’s Ernani. James Levine conducts the Metropolitan Opera orchestra and chorus.Permalink

September 30, 2019. Horowitz and Oistrakh. Two supremely gifted musicians with very similar beginnings but vastly different career paths were born this week, the pianist Vladimir Horowitz and the violinist David Oistrakh. Both Jewish, they were born in Ukraine, then a part of the Russian Empire: Horowitz in Kiev, on October 1st of 1903, Oistrakh in Odessa, on September 30th of 1908. Rampant anti-Semitism notwithstanding, both were born into rather well-to-do families: Horowitz’s father was an electrical engineer, while Oistrakh’s – a merchant of the “second guild,” the reason both families were allowed to live in large cities outside of the Pale of Settlement. Horowitz’s first pianos teacher was his mother, a pianist; he then attended the Kiev Conservatory where one of his professors was Felix Blumenfled, a brilliant pianist and teacher (Maria Yudina was one of his students). Oistrakh’s talents were also obvious from a very early age; he became a pupil of the famous Pyotr Stolyarsky, the founder of the Odessa school of violin playing (among Stolyarsky’s students were Nathan Milstein, Boris “Busya” Goldstein, Elizabeth Gilels and

Horowitz and the violinist David Oistrakh. Both Jewish, they were born in Ukraine, then a part of the Russian Empire: Horowitz in Kiev, on October 1st of 1903, Oistrakh in Odessa, on September 30th of 1908. Rampant anti-Semitism notwithstanding, both were born into rather well-to-do families: Horowitz’s father was an electrical engineer, while Oistrakh’s – a merchant of the “second guild,” the reason both families were allowed to live in large cities outside of the Pale of Settlement. Horowitz’s first pianos teacher was his mother, a pianist; he then attended the Kiev Conservatory where one of his professors was Felix Blumenfled, a brilliant pianist and teacher (Maria Yudina was one of his students). Oistrakh’s talents were also obvious from a very early age; he became a pupil of the famous Pyotr Stolyarsky, the founder of the Odessa school of violin playing (among Stolyarsky’s students were Nathan Milstein, Boris “Busya” Goldstein, Elizabeth Gilels and other future stars; Milstein, Oistrakh’s good friend, was a link to Horowitz, as just several years later the two of them extensively toured the country together). Oistrakh entered the Odessa Conservatory in 1923, graduating in 1926, at the age of 18. By the mid-1920s both Horowitz and Oistrakh were already famous. Horowitz played more than 150 different pieces during his “Leningrad series” in November 1924 – January 1925; the breadth of the repertoire and the quality of his playing were “stunning” – that’s how the Culture minister, Lunacharsky, characterized the concerts in one of his anonymous reviews. The younger Oistrakh was also playing widely, but mostly in Ukraine. The mid-20s is when their careers took very different turns. In 1925, Horowitz received permission to go to Germany, ostensibly to study; he stayed in the West and returned to the Soviet Union only 60 years later, on a belated but triumphal tour. For several years he performed all over Europe, with enormous success (in 1926, during his Paris Opera concert, the gendarmes were called in to pacify the overexcited crowd which started smashing the seats). Horowitz’s calling card was Tchaikovsky’s First Piano concerto. That was the piece he played during his debut concert with the New York Philharmonic under the direction of Thomas Beecham. Here’s what happened during that concert: “Horowitz broke from Beecham’s stately tempo and charged to the finale several measures before the orchestra. The result was, at once, vulgar and exhilarating, and Beecham fumed at the podium as the audience shouted their appreciation for Horowitz. Critics, too, overlooked his questionable taste and bestowed wild praise on his spellbinding technique” (from encyclopedia.com). In 1933 Horowitz married Arturo Toscanini’s daughter Wanda; they settled in the US in 1939. Horowitz’s phenomenal career continued but with interruptions: a neurotic, he did not play in public between 1936-38, 1953-65 and 1969-74. Horowitz is remembered mostly for his superhuman technique, but we shouldn’t forget his singing sound, the unique color he could produce in any piece, no matter how technically challenging. Here’s the 1930 recording of Liszt’s Etude no. 2in E-flat Major s 14/2 (after Paganini’s Caprice no. 17).

other future stars; Milstein, Oistrakh’s good friend, was a link to Horowitz, as just several years later the two of them extensively toured the country together). Oistrakh entered the Odessa Conservatory in 1923, graduating in 1926, at the age of 18. By the mid-1920s both Horowitz and Oistrakh were already famous. Horowitz played more than 150 different pieces during his “Leningrad series” in November 1924 – January 1925; the breadth of the repertoire and the quality of his playing were “stunning” – that’s how the Culture minister, Lunacharsky, characterized the concerts in one of his anonymous reviews. The younger Oistrakh was also playing widely, but mostly in Ukraine. The mid-20s is when their careers took very different turns. In 1925, Horowitz received permission to go to Germany, ostensibly to study; he stayed in the West and returned to the Soviet Union only 60 years later, on a belated but triumphal tour. For several years he performed all over Europe, with enormous success (in 1926, during his Paris Opera concert, the gendarmes were called in to pacify the overexcited crowd which started smashing the seats). Horowitz’s calling card was Tchaikovsky’s First Piano concerto. That was the piece he played during his debut concert with the New York Philharmonic under the direction of Thomas Beecham. Here’s what happened during that concert: “Horowitz broke from Beecham’s stately tempo and charged to the finale several measures before the orchestra. The result was, at once, vulgar and exhilarating, and Beecham fumed at the podium as the audience shouted their appreciation for Horowitz. Critics, too, overlooked his questionable taste and bestowed wild praise on his spellbinding technique” (from encyclopedia.com). In 1933 Horowitz married Arturo Toscanini’s daughter Wanda; they settled in the US in 1939. Horowitz’s phenomenal career continued but with interruptions: a neurotic, he did not play in public between 1936-38, 1953-65 and 1969-74. Horowitz is remembered mostly for his superhuman technique, but we shouldn’t forget his singing sound, the unique color he could produce in any piece, no matter how technically challenging. Here’s the 1930 recording of Liszt’s Etude no. 2in E-flat Major s 14/2 (after Paganini’s Caprice no. 17).

David Oistrakh’s career was indeed very different. In 1927 he moved to Moscow; in 1935 he won the 2nd All-Soviet Performer’s competition, that same year he received the 2nd prize at the Wieniawski competition (after Ginette Neveu) and two years later won the Ysaÿe International competition. He was acknowledged as the no. 1 Soviet violinist, a very special position in the country were arts were state-sponsored and politicized. Oistrakh was allowed to tour the West (he went to the US in 1955 and performed to great success) and was given numerous awards. Oistrakh’s technique was impeccable, the sound – powerful, and while he may not have been the warmest player, his sense of style was impeccable. Here’s David Oistrakh performing live in 1954: La Campanella from Paganini’s Violin Concerto.Permalink