Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

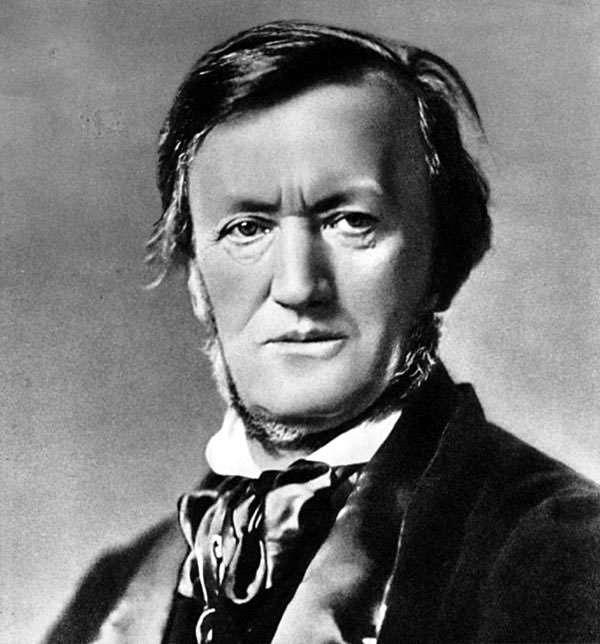

May 20, 2019. Wagner, Alicia de Larrocha. Richard Wagner was born on May 22nd of 1813. For some years we’ve been following Wagner’s life thru his operas; two years ago we arrived at 1848, the year Wagner started working on the monumental Der Ring des Nibelungen. It is hard to imagine, but during the years leading up to the Revolution of 1848 Wagner was involved in left-wing politics. He was living in Dresden and active among the local socilaists; he knew Mikhail Bakunin, the famous anarchist, and read Ludwig Feuerbach, a philosopher important in Marxist thought. Wagner participated in the May 1848 uprising and had to flee Germany to avoid arrest. He settled in Zurich, lonely and poor, existing mostly on small funds provided by his friends. While he did finish Lohengrin, very little music was composed in the next several years. What Wagner was writing were articles: some on the art of opera, but also the dreadful Judaism in Music, the first of his many antisemitic pieces. An influential Opera and Drama expounded the concept of music drama and “total work of art,” which he subsequently used in Der Ring. Wagner wrote librettos to all of his operas; first he would create a rough sketch, then a draft in prose, for the Ring he would also versify it in alliterative form, the style of old German legends. Sometime around 1848 Wagner started working on a libretto about the mythical German hero, Siegfried, which he planned to call Siegfried's Death. He read many ancient German and Norse sagas (he had some knowledge of Old Norse and Middle German) and commentaries written by the Grimm brothers. Eventually he decided to expand the project to two or three operas; but ultimately it became four: Siegfried's Death turned into the last opera in the tetralogy, Götterdämmerung, or Twilight of the Gods. The preceding three librettos were finished and named in 1852; they were Das Rheingold (The Rhine Gold), which serves as the prologue; Die Walküre (The Valkyrie), and Siegfried. The librettos were written in reverse chronological order, Das Rheingold coming in last. The music, on the other hand, was composed more or less in the order the operas are presented: even though some music for Die Walküre was composed earlier, Das Rheingold was the first one to be finished, in January of 1854 (Die Walküre was completed two years later). It was premiered in Munich in September of 1869 against the wishes of Wagner, who preferred to stage the complete tetralogy (Götterdämmerung was finished only in 1874). The Bayreuth premier took place in August of 1876, in the newly built theater, the Bayreuth Festspielhaus. We have a sample of the Prelude to Act I (here); about two and a half hours later, in the final scene, Wotan leads the gods into his newly built castle-fortress, Valhalla (Zubin Mehta conducts the New York Philharmonic Orchestra in this 1983 recording).

hard to imagine, but during the years leading up to the Revolution of 1848 Wagner was involved in left-wing politics. He was living in Dresden and active among the local socilaists; he knew Mikhail Bakunin, the famous anarchist, and read Ludwig Feuerbach, a philosopher important in Marxist thought. Wagner participated in the May 1848 uprising and had to flee Germany to avoid arrest. He settled in Zurich, lonely and poor, existing mostly on small funds provided by his friends. While he did finish Lohengrin, very little music was composed in the next several years. What Wagner was writing were articles: some on the art of opera, but also the dreadful Judaism in Music, the first of his many antisemitic pieces. An influential Opera and Drama expounded the concept of music drama and “total work of art,” which he subsequently used in Der Ring. Wagner wrote librettos to all of his operas; first he would create a rough sketch, then a draft in prose, for the Ring he would also versify it in alliterative form, the style of old German legends. Sometime around 1848 Wagner started working on a libretto about the mythical German hero, Siegfried, which he planned to call Siegfried's Death. He read many ancient German and Norse sagas (he had some knowledge of Old Norse and Middle German) and commentaries written by the Grimm brothers. Eventually he decided to expand the project to two or three operas; but ultimately it became four: Siegfried's Death turned into the last opera in the tetralogy, Götterdämmerung, or Twilight of the Gods. The preceding three librettos were finished and named in 1852; they were Das Rheingold (The Rhine Gold), which serves as the prologue; Die Walküre (The Valkyrie), and Siegfried. The librettos were written in reverse chronological order, Das Rheingold coming in last. The music, on the other hand, was composed more or less in the order the operas are presented: even though some music for Die Walküre was composed earlier, Das Rheingold was the first one to be finished, in January of 1854 (Die Walküre was completed two years later). It was premiered in Munich in September of 1869 against the wishes of Wagner, who preferred to stage the complete tetralogy (Götterdämmerung was finished only in 1874). The Bayreuth premier took place in August of 1876, in the newly built theater, the Bayreuth Festspielhaus. We have a sample of the Prelude to Act I (here); about two and a half hours later, in the final scene, Wotan leads the gods into his newly built castle-fortress, Valhalla (Zubin Mehta conducts the New York Philharmonic Orchestra in this 1983 recording).

The great Spanish pianist, Alicia de Larrocha was born on May 23rd of 1923 in Barcelona. She gave her first performance at the age of five and played a Mozart concerto with the Madrid Symphony Orchestra at 11. Alicia de Larrocha studied with Frank Marshall, a pupil of Granados, and later became the director of the Marshall Music Academy. She was an incomparable performer of the music of Spanish composers, especially Albéniz and Granados. She was short in stature (4’9”) and had small hands but played all the “big” concertos (her hands had good stretch). In the second half of her career she played Mozart more often. Here is Mozart’s Piano Sonata, K.570 in B-flat major.Permalink

May 13, 2019. Monteverdi, Satie, Klemperer. One of the most important composers in the history of European music, Claudio Monteverdi was born on May 15th of 1567 in Cremona. Rarely can we associate historically significant musical or esthetic developments with just one person, but Monteverdi is one of them: early in his life he wrote wonderful madrigals in the style of late Renaissance, and then transitioned to what we now call Baroque. In the process, he practically invented a new art form, the opera. You can read about him here, here and here. As a musical excerpt, we have his Lament of Arianna. We know it as a madrigal from Book Six, published in Venice in 1614, but originally it was composed or his early opera Arianna, now lost. Here it is performed by the Concerto Italiano under the direction of Rinaldo Alessandrini.

Rarely can we associate historically significant musical or esthetic developments with just one person, but Monteverdi is one of them: early in his life he wrote wonderful madrigals in the style of late Renaissance, and then transitioned to what we now call Baroque. In the process, he practically invented a new art form, the opera. You can read about him here, here and here. As a musical excerpt, we have his Lament of Arianna. We know it as a madrigal from Book Six, published in Venice in 1614, but originally it was composed or his early opera Arianna, now lost. Here it is performed by the Concerto Italiano under the direction of Rinaldo Alessandrini.

In some sense, Erik Satie, born on May 17th of 1866 in Honfleur to a French father and Scottish mother, was the opposite of Monteverdi: his musical output was slim (he’s mostly remembered for his Gymnopédies and Gnossiennes), his influence coming as much from his personality as his music. Satie was an eccentric (he ate only white-colored food, carried a hammer for protection and was involved in the occult). Still, he knew and was known to “everybody” of significance in the pre-WWI Paris. He had a long affair with Suzanne Valadon, a painter and mother of Morice Utrillo, was good friends with Ravel and Debussy and influenced Les Six. Later he got involved with the Dadaists and Surrealists. And, of course, he paved the way for the Minimalists. Here are three Gymnopédies, each about three and a half minutes long, performed by Jean-Yves Thibaudet, the Frenchman who recorded all piano works by Satie.

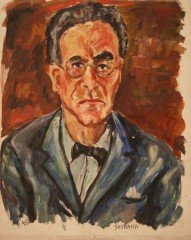

Otto Klemperer, one of the greatest conductors of his generation, was born on May 14th of 1885 in Breslau, Germany (now Wrocław, Poland). In 1905 he met Mahler, who helped Klemperer to get the conducting position at Neues Deutsches Theater in Prague, which launched Klemperer’s conducting career. He went on to conduct at several important opera houses; in 1927 he was appointed the music director of the Kroll Opera, a branch of the Berlin Staatsoper, created to promote contemporary music. There he conducted new operas by Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Hindemith and Janáček. Some of the Kroll Opera’s Wagner productions were so innovative that they affected the Bayreuth enactments half a century later. During that time, Klemperer also conducted the Kroll Concerts, where he performed significant contemporary pieces. In 1931 the Kroll Opera closed for lack of financing, but Klemperer remained at the Staatsoper. In 1933 the Nazis took over and Klemperer, who was Jewish, emigrated to the US. His first appointment was with the Los Angeles Philharmonic; his tenure there brought critical acclaim, but he wasn’t comfortable in Southern California, he preferred the East coast. He played several concerts with the New York Philharmonic, but when, in 1936, the position of Music Director opened with the departure of Arturo Toscanini, the orchestra board engaged John Barbirolli and, later, Artur Rodziński. Klemperer was hugely disappointed; he remained with the LA Phil till 1939 when a tumor was found in his brain. It was successfully removed but left Klemperer unable to conduct for several years. After the war he made several recordings with the newly created Philharmonia Orchestra in London and in 1959 was appointed its “Director for life.” He had a wonderful relationship with the musicians and made several remarkable recordings of Beethoven and Mahler’s symphonies. Klemperer died in Zurich on July 6th of 1973. Here’s the first movement of Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony, recorded in 1957. Otto Klemperer conducts the Philharmonia Orchestra.Permalink

1885 in Breslau, Germany (now Wrocław, Poland). In 1905 he met Mahler, who helped Klemperer to get the conducting position at Neues Deutsches Theater in Prague, which launched Klemperer’s conducting career. He went on to conduct at several important opera houses; in 1927 he was appointed the music director of the Kroll Opera, a branch of the Berlin Staatsoper, created to promote contemporary music. There he conducted new operas by Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Hindemith and Janáček. Some of the Kroll Opera’s Wagner productions were so innovative that they affected the Bayreuth enactments half a century later. During that time, Klemperer also conducted the Kroll Concerts, where he performed significant contemporary pieces. In 1931 the Kroll Opera closed for lack of financing, but Klemperer remained at the Staatsoper. In 1933 the Nazis took over and Klemperer, who was Jewish, emigrated to the US. His first appointment was with the Los Angeles Philharmonic; his tenure there brought critical acclaim, but he wasn’t comfortable in Southern California, he preferred the East coast. He played several concerts with the New York Philharmonic, but when, in 1936, the position of Music Director opened with the departure of Arturo Toscanini, the orchestra board engaged John Barbirolli and, later, Artur Rodziński. Klemperer was hugely disappointed; he remained with the LA Phil till 1939 when a tumor was found in his brain. It was successfully removed but left Klemperer unable to conduct for several years. After the war he made several recordings with the newly created Philharmonia Orchestra in London and in 1959 was appointed its “Director for life.” He had a wonderful relationship with the musicians and made several remarkable recordings of Beethoven and Mahler’s symphonies. Klemperer died in Zurich on July 6th of 1973. Here’s the first movement of Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony, recorded in 1957. Otto Klemperer conducts the Philharmonia Orchestra.Permalink

May 6, 2019. Neither Brahms nor Tchaikovsky. By an unfortunate coincidence for us, two great 19th century composers were born on the same date, March 7th: Johannes Brahms in 1833 and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky in 1840. Both are important and influential: Brahms as the key developer of the Beethoven symphonic tradition, Tchaikovsky as the central figure in the new Russian music. Every year we contrive to write about both in one short entry, fully recognizing how different their music is, even if there are some curious formal similarities. This year we’ll skip both and write about (or at least mention) composers and performers admittedly not as consequential but who deserve our attention. And this is a large and colorful group. Jules Massenet and Gabriel Fauré, two well-known French composers were born on May 12th, the former in 1842, the latter three years later. Massenet, a conservative composer of the Belle Époque, is famous for two of his operas, Manon and Werther; a much more adventuresome Fauré influenced generations of French composers, from the Impressionists to Les Six. Another Frenchman, from an earlier era, Jean-Marie Leclair, is known as the father of the French violin school; he was also born this week, on May 10th of 1697. There are two Italians -- Giovanni Battista Viotti, who like Leclair, was famous for his violin concertos (he was born on May 12th of 1755) and Giovanni Paisiello, now almost forgotten but in the late 18th century famous for his operas that were staged all across Europe (he was born on May 9th of 1740). Then there was another early-Classical composer, the German Carl Stamitz of the Stamitz family which also gave us Anton and Johan Stamitzs (Carl was born on May 8th of 1745). Jan Václav Voříšek was a very fine composer: born in Bohemia on May 11th of 1791, he spent the most productive years of his life in Vienna, where he met Beethoven and befriended Schubert. Voříšek died of tuberculosis in 1825, at just 34 years old. Here’s his Symphony in D Major, performed by the Chicago Sinfonietta, Paul Freeman conducting. Anatol Liadov was a minor but pleasant composer of short piano pieces. Were it not for his laziness and lack for self-assurance, he might’ve developed into a major talent (Liadov was born on May 12th of 1855). And let’s not forget Milton Babbitt, one of the most important American composers and teachers of the second half of the 20th century, influential not only in the US but in Europe as well; he was born on May 10th of 1916.

another early-Classical composer, the German Carl Stamitz of the Stamitz family which also gave us Anton and Johan Stamitzs (Carl was born on May 8th of 1745). Jan Václav Voříšek was a very fine composer: born in Bohemia on May 11th of 1791, he spent the most productive years of his life in Vienna, where he met Beethoven and befriended Schubert. Voříšek died of tuberculosis in 1825, at just 34 years old. Here’s his Symphony in D Major, performed by the Chicago Sinfonietta, Paul Freeman conducting. Anatol Liadov was a minor but pleasant composer of short piano pieces. Were it not for his laziness and lack for self-assurance, he might’ve developed into a major talent (Liadov was born on May 12th of 1855). And let’s not forget Milton Babbitt, one of the most important American composers and teachers of the second half of the 20th century, influential not only in the US but in Europe as well; he was born on May 10th of 1916.

Several noted interpreters were also born this week, for example Vladimir Sofronitsky, on May 8th of 1901, a socially awkward but greatly talented Russian-Soviet pianist. He’s not well known in the West but was considered the supreme interpreter of the music of Scriabin and Chopin in the Soviet Union. Scriabin was his favorite composer; Sofronitsky’s first wife was Scriabin’s daughter, and by the end of his life he stopped giving concerts at the large Great Hall of Moscow Conservatory, and performed instead in one of the rooms of the Scriabin museum (the composer lived the three last years of his life, from 1921 to 1915 on the first floor of this lovely mansion on one of the side streets in the center of Moscow). Here’s Scriabin’s Poeme Op. 36 (Satanique), recorded live in 1960.

Two very important conductors also have their anniversaries this week: Jascha Horenstein, who was born in Kiev on May 6th of 1898, lived and performed in Vienna and Berlin, but in 1933, because of the growing antisemitism, left for Paris and then for the US. Horenstein was a renowned Mahlerian. Also, Carlo Maria Giulini, an Italian conductor with a major career both in Europe and the US; he was born on May 9th of 1914.Permalink

April 29, 2019. Alessandro Scarlatti, the father of the by now more famous Domenico , was born on May 2nd of 1660 in Palermo. One of the greatest opera composers of the late 17th.jpg) century, he’s not very popular these days, mostly because the specific art form to which he was devoted – the Baroque opera – isn’t very popular. Baroque operas are often long, expensive to stage, and there are not that many voices around that could do justice to their music. No opera can withstand bad singing, neither a Verdi nor a Mozart, but a bad production of a Baroque opera can bore one to tears. On the other hand, listen to the aria Mentr'io godo in dolce oblio, from Il Giardino di Rose: La Santissima Vergine del Rosario, performed by Cecilia Bartoli and Les Musiciens du Louvre. Isn’t it absolutely exquisite? We’ve written about Alessandro on a number of occasions (for example, here and here), so let’s just listen to one of his sacred compositions, the Stabat Mater. Scaraltti wrote three versions of Stabat Mater, this is the latest, from 1724, composed one year before Scarlatti’s death on October 22nd of 1725 (Concerto Italiano is conducted by Rinaldo Alessandrini). An interesting historical note: Scarlatti’s Stabat Mater was written for the noble fraternity of the church of S Maria dei Sette Dolori in Naples. Eleven years later, the fraternity ordered a replacement from the 26-year-old but already very ill Giovanni Battista Pergolesi; it turned out to be Pergolesi’s last work. We don’t doubt the quality of Pergolesi’s work, but also think that Alessandro Scarlatti’s Stabat mater is a work of first order.

century, he’s not very popular these days, mostly because the specific art form to which he was devoted – the Baroque opera – isn’t very popular. Baroque operas are often long, expensive to stage, and there are not that many voices around that could do justice to their music. No opera can withstand bad singing, neither a Verdi nor a Mozart, but a bad production of a Baroque opera can bore one to tears. On the other hand, listen to the aria Mentr'io godo in dolce oblio, from Il Giardino di Rose: La Santissima Vergine del Rosario, performed by Cecilia Bartoli and Les Musiciens du Louvre. Isn’t it absolutely exquisite? We’ve written about Alessandro on a number of occasions (for example, here and here), so let’s just listen to one of his sacred compositions, the Stabat Mater. Scaraltti wrote three versions of Stabat Mater, this is the latest, from 1724, composed one year before Scarlatti’s death on October 22nd of 1725 (Concerto Italiano is conducted by Rinaldo Alessandrini). An interesting historical note: Scarlatti’s Stabat Mater was written for the noble fraternity of the church of S Maria dei Sette Dolori in Naples. Eleven years later, the fraternity ordered a replacement from the 26-year-old but already very ill Giovanni Battista Pergolesi; it turned out to be Pergolesi’s last work. We don’t doubt the quality of Pergolesi’s work, but also think that Alessandro Scarlatti’s Stabat mater is a work of first order.

For a long time, Stabat Mater, a 13th-centry hymn to the Virgin Mary, was almost a requisite composition. During the Renaissance it was set to music by such composers as Josquin des Prez, Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, Orlando di Lasso; during the Baroque, Domenico Scarlatti and Antonio Vivaldi wrote their versions. Haydn was one of the Classical composers to write a Stabat Mater, Schubert did it twice. Later in the 19th century, Rossini, Liszt, Gounod, Dvořák and Verdi did the same. In the 20th century it was Kodály, Szymanowski, Poulenc, Arvo Pärt and Krzysztof Penderecki’s turn. And there are many more: there is a site dedicated to different versions of Stabat Mater, https://www.stabatmater.info, they list 250 (!) different compositions. The site is very much worth a visit. Here’s Stabat Mater by Lasso, composed in 1585. It’s performed by The Hilliard Ensemble.

Two prominent conductors were born on this day: Thomas Beecham in 1879 and Zubin Mehta in 1936. Beecham was born into a wealthy family, which allowed him to stage operas and create orchestras. Self-taught as a conductor, he debuted in 1902. In 1906 he was invited to the New Symphony Orchestra, a chamber ensemble which he expanded to the size of a symphony orchestra. In 1909 he founded the Beecham Symphony Orchestra. He brought Diagilev’s Ballets Russes to London and premiered five of Richard Strauss’s operas. In 1932 he and his younger colleague Malcolm Sargent founded The London Philharmonic Orchestra, now one of the five permanent London orchestras. He didn’t stop there: in 1946, he founded The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, another of the London Big Five, and conducted it till the end of his life (Beecham died on March 8th of 1961). He was called Britain’s first internationally-renowned conductor; he made a large number of recordings, some excellent; his importance to British music cannot be overestimated. As for, Zubin Mehta, who turned 83 today, he’s still quite active as the music director of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra.Permalink

April 22, 2019. Prokofiev and Menuhin. Sergei Prokofiev was born on April 27th of 1891. He’s one of our favorites, and we’ve written about him year after year (and, of course, on his 125th anniversary). His short Piano sonata no. 3, op. 28, an early masterpiece, was premiered by.jpg) Prokofiev himself on April 15th of 1918 in St. Petersburg (then, Petrograd). By then, Prokofiev had already made the decision to leave for America. He applied to Anatoly Lunacharsky, the Commissar of Culture, for permission to leave, and received it shortly after. Just three weeks after the concert, on May 7th of 1918, Prokofiev left Petrograd and travelled through Siberia to Vladivostok and then on to Tokyo. He gave several concerts in Japan, boarded a ship and arrived in New York in September of 1918. Here’s what our own Joseph DuBose wrote in the notes to the Sonata: “Sergei Prokofiev composed his Third and Fourth Piano Sonatas in 1917. Both sonatas bore the subtitle “D'après de vieux cahiers,” or “From Old Notebooks,” and were wrought from sketches the composer had made a decade earlier during his student years at the St. Petersburg Conservatory. The Third Sonata, in A minor, marked a significant departure for the composer, its demeanor being far more serious than its predecessor... Like his First Piano Sonata composed in 1909, the Third is comprised of a single movement in sonata form. Where the First Sonata was segmented in its form and even derivative, the Third is evidently the work of a more mature mind, one that has learned to follow the natural course of its ideas and allows the form to proceed organically from them. It juxtaposes two diverse themes—an angular theme in Prokofiev’s “motoric” style, and a lyrical second theme. Both themes are then worked extensively in the Sonata’s development… The Third Piano Sonata is regarded as one of Prokofiev’s best compositions for piano, and, interestingly, was one of his few works to receive similar praise from critics.” Here it is in the performance by the pianist Andrei Gavrilov.

Prokofiev himself on April 15th of 1918 in St. Petersburg (then, Petrograd). By then, Prokofiev had already made the decision to leave for America. He applied to Anatoly Lunacharsky, the Commissar of Culture, for permission to leave, and received it shortly after. Just three weeks after the concert, on May 7th of 1918, Prokofiev left Petrograd and travelled through Siberia to Vladivostok and then on to Tokyo. He gave several concerts in Japan, boarded a ship and arrived in New York in September of 1918. Here’s what our own Joseph DuBose wrote in the notes to the Sonata: “Sergei Prokofiev composed his Third and Fourth Piano Sonatas in 1917. Both sonatas bore the subtitle “D'après de vieux cahiers,” or “From Old Notebooks,” and were wrought from sketches the composer had made a decade earlier during his student years at the St. Petersburg Conservatory. The Third Sonata, in A minor, marked a significant departure for the composer, its demeanor being far more serious than its predecessor... Like his First Piano Sonata composed in 1909, the Third is comprised of a single movement in sonata form. Where the First Sonata was segmented in its form and even derivative, the Third is evidently the work of a more mature mind, one that has learned to follow the natural course of its ideas and allows the form to proceed organically from them. It juxtaposes two diverse themes—an angular theme in Prokofiev’s “motoric” style, and a lyrical second theme. Both themes are then worked extensively in the Sonata’s development… The Third Piano Sonata is regarded as one of Prokofiev’s best compositions for piano, and, interestingly, was one of his few works to receive similar praise from critics.” Here it is in the performance by the pianist Andrei Gavrilov.

One of the greatest violinists of the 20th century, Yehudi Menuhin, was also born this week, on April 22nd of 1916, in New York. He started his lessons at the age of five; by then he was living in San Francisco, where his family settled in 1918. At the age of seven he played in public for the first time, a year later he gave a full recital (both times in San Francisco), at nine he debuted in New York and the same year played his first concert with the San Francisco Symphony. At the age of 12 he played violin concertos by Bach, Beethoven and Brahms with the Berlin Philharmonic under the direction of Bruno Walter and a week later he went to Dresden and repeated the program at Semperoper with the Dresden Staatscapelle. He studied with Adolf Busch in Basel and in the early 1930s moved to Paris where George Enescu became his teacher. In the late 30s he moved back to California but continued performing around the world. During WWII he gave 500 concerts for the US troops; he was the first to play at the Opéra of the just liberated Paris, to the survivors of the Belsen concentration camp; he was also the first Jewish musician to perform with the Berlin Philharmonic, with Wilhelm Furtwängler conducting. In mid-career, Menuhin experienced a crisis: his phenomenal technique abandoned him. “As a child, I never practiced scales and things like that either; and now that I find myself often playing every other night, I see my technical problems accumulating,” he said in his autobiography. To continue performing, he had to rethink his technique; his new approach and insights eventually led him to openi an international music school. Here is Yehudi Menuhin performing Bach’s Chaconne from Partita no. 2. The recording was made in 1956.Permalink

At the age of 12 he played violin concertos by Bach, Beethoven and Brahms with the Berlin Philharmonic under the direction of Bruno Walter and a week later he went to Dresden and repeated the program at Semperoper with the Dresden Staatscapelle. He studied with Adolf Busch in Basel and in the early 1930s moved to Paris where George Enescu became his teacher. In the late 30s he moved back to California but continued performing around the world. During WWII he gave 500 concerts for the US troops; he was the first to play at the Opéra of the just liberated Paris, to the survivors of the Belsen concentration camp; he was also the first Jewish musician to perform with the Berlin Philharmonic, with Wilhelm Furtwängler conducting. In mid-career, Menuhin experienced a crisis: his phenomenal technique abandoned him. “As a child, I never practiced scales and things like that either; and now that I find myself often playing every other night, I see my technical problems accumulating,” he said in his autobiography. To continue performing, he had to rethink his technique; his new approach and insights eventually led him to openi an international music school. Here is Yehudi Menuhin performing Bach’s Chaconne from Partita no. 2. The recording was made in 1956.Permalink

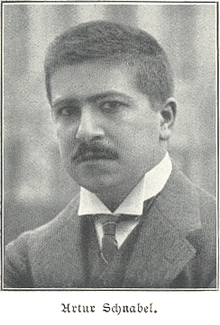

April 15, 2019. Three pianists and two conductors. This week we’ll celebrate several interpreters, rather than creators, of music: pianists Schnabel, Sokolov and Perahia, and conductors Stokowski and John Eliot Gardiner. Artur Schnabel, born on April 17th of 1882, was one of the most important pianists of the first half of the 20th century. Schnabel was Jewish, born Aaron, in a small town in Moravia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian empire. His family moved to Vienna when he was seven. His piano teacher was the famous Theodor Leschetizky, who said to Schnabel, “You will never be a pianist; you are a musician” and had him play Schubert’s sonatas rather than the popular bravura pieces by Liszt. In 1898 Schnabel moved to Berlin, the place where his career flourished till Nazis took over in 1933. He performed with all the greatest conductors of the time (Furtwängler, Walter and Klemperer among them) and toured the major concert halls in Europe and America. Schnabel left Berlin in 1933, first for England, and then, in 1939, for the US. While in England, he made the first ever recording of all the piano sonatas by Beethoven (they were made in the course of several years, from 1932 to 1935 at Abbey Road Studios in London). In 1944 he became a US citizen. Here’ is Beethoven’s Sonata no. 25, op. 78 in that historic London recording.

conductors Stokowski and John Eliot Gardiner. Artur Schnabel, born on April 17th of 1882, was one of the most important pianists of the first half of the 20th century. Schnabel was Jewish, born Aaron, in a small town in Moravia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian empire. His family moved to Vienna when he was seven. His piano teacher was the famous Theodor Leschetizky, who said to Schnabel, “You will never be a pianist; you are a musician” and had him play Schubert’s sonatas rather than the popular bravura pieces by Liszt. In 1898 Schnabel moved to Berlin, the place where his career flourished till Nazis took over in 1933. He performed with all the greatest conductors of the time (Furtwängler, Walter and Klemperer among them) and toured the major concert halls in Europe and America. Schnabel left Berlin in 1933, first for England, and then, in 1939, for the US. While in England, he made the first ever recording of all the piano sonatas by Beethoven (they were made in the course of several years, from 1932 to 1935 at Abbey Road Studios in London). In 1944 he became a US citizen. Here’ is Beethoven’s Sonata no. 25, op. 78 in that historic London recording.

Who would’ve thought, in 1966, that the 16-year-old Grigory Sokolov, the unexpected winner of the Third Tchaikovsky Piano competition, would turn into one of the most interesting and introspective pianists of the generation? Back then the Moscow public was rooting for Misha Dichter and suspected that Sokolov’s win was a result of the Soviet cultural officialdom manipulations. For the following 25-something years Sokolov’s career went nowhere, till his concerts in Europe and the US in 1990. These days Sokolov is a cult figure. He doesn’t record in the studio but allows his live concerts to be recorded (in that he’s the exact opposite of Glenn Gould). Sokolov has a huge repertoire; he’s famous as a great interpreter of Bach, Schubert, Schumann, Rameau and other classics. Here’s Haydn’s piano sonata no.47 in B minor, Hob.XVI:32, recorded live in Munich in 2018.

Somehow all the pianists we’re celebrating today have Jewish roots. Schnabel was Jewish, Sokolov – half Jewish (by his father, his mother was Russian). Not that it matters, but Murray Perahia, one of the most interesting pianists of the last quarter of the century, is also Jewish – a Sephardim, as opposed to the Ashkenazi Schnabel and Sokolov. Perahia has a broad repertoire, but his Bach is especially interesting – as far from Glenn Gould’s as one can imagine, but as exciting. In 1990 Perahia suffered an injury to his hand and his problems persisted for many years. He has recovered and records and plays concerts in the US and Europe. Here’s Bach’s English Suite no. 1 in Murray Perahia’s 1997 recording.

Two conductors, Leopold Stokowski and John Eliot Gardiner, were also born this week, Stokowski on April 18th of 1882, one day after Schnabel, Gardiner on April 20th of 1943. Stokowski, the Philadelphia Orchestra’s music director from 1912 to 1938, reigned supreme in the first half of the 20th century, and even though his idiosyncratic performances seem dated these days, he clearly was a magnificent conductor. Gardiner, on the other hand, is one of the most interesting Bach interpreters, and is going close to the source. We’ll write more about both later.Permalink