Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

September 23, 2019. Rameau and more. We have a large group of celebrants this week, and we’ll try to address all of them, even if only cursorily. Jean-Philippe Rameau is the oldest of them, he was born on September 25th of 1683 in Dijon. If Jean-Baptiste Lully created the grand French opera, it was Rameau, half a century later, who perfected it. One of many great examples of his art is Castor and Pollux, his tragédie en musique, musical tragedy as it was called at the time, similar to the Italian opera seria. Castor and Pollux was Rameau’s third opera (he started writing them only at age of 50 – before that he wrote mostly music for the harpsichord, much of it of the highest quality, and some choral music). Castor was premiered on October 24th of 1737 by the Académie Royale de Musique (the Royal Opera, founded in 1669 on the orders of Louis XIV and lead by Lully) at its theatre in the Palais-Royal (in our time the Opera performs at the Opéra Bastille and the Palais Garnier). Here’s Agnès Mellon in the aria Tristes Apprêts, with the ensemble Les Arts Florissants under the direction of William Christie.

them, he was born on September 25th of 1683 in Dijon. If Jean-Baptiste Lully created the grand French opera, it was Rameau, half a century later, who perfected it. One of many great examples of his art is Castor and Pollux, his tragédie en musique, musical tragedy as it was called at the time, similar to the Italian opera seria. Castor and Pollux was Rameau’s third opera (he started writing them only at age of 50 – before that he wrote mostly music for the harpsichord, much of it of the highest quality, and some choral music). Castor was premiered on October 24th of 1737 by the Académie Royale de Musique (the Royal Opera, founded in 1669 on the orders of Louis XIV and lead by Lully) at its theatre in the Palais-Royal (in our time the Opera performs at the Opéra Bastille and the Palais Garnier). Here’s Agnès Mellon in the aria Tristes Apprêts, with the ensemble Les Arts Florissants under the direction of William Christie.

Two composers, who worked under the Communist regimes of Eastern Europe, were born this week: Dmitry Shostakovich in St.-Petersburg, Russia, on September 25th of 1906, and Andrzej Panufnik, on September 24th of 1914, in Warsaw. The very talented Shostakovich became the national Soviet composer, even though during his long composing career he was threatened many times, and his music was occasionally banned; Panufnik, on the other hand, defected from Poland to the UK (you can read more about him here).

We’ve never written about the Armenian composer Komitas, the founder of the modern national school of music, who was born on September 26th of 1869 in Kütahya in Anatolia, Turkey, where many Armenians lived. Orphaned at 14, he was sent to a seminary in Etchmiadzin, the religious center of Armenia. It was during his years in Etchmiadzin that his love for music, especially Armenian folk music, became apparent. He started collecting local songs, as Bartók would do in Hungary some years later. In 1895 Komitas moved to Tbilisi (then Tiflis), the Georgian capital with a large Armenian community, and a year later – to Berlin where he studied at the prestigious Frederick William (now Humboldt) University. In 1899 he returned to Etchmiadzin and continued collected and publishing folk songs, eventually gathering 3000 pieces of music. In 1910 he moved to Constantinople, where he organized a choir; he toured widely with it, visiting France where his music was admired by Debussy, Saint-Saëns and Gabriel Fauré. In 1915, during the early days of the Armenian Genocide, he was deported to northern Anatolia. The hardships of exile deeply affected Komitas, and he returned to Constantinople a broken man. He was hospitalized and later moved to a psychiatric clinic in France, where lived for almost 20 years, never recovering. He died on October 22nd of 1935; a year later his remains were moved to Yerevan’s Pantheon of Armenian cultural figures. Here’s Komitas’s song “Krunk” (The Crane), transcribed by Georgy Saradjian and performed by Evgeny Kissin in 2015 during the series “With you Armenia,” dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide.

George Gershwin was also born this week, on September 26th of 1898. And then there is a whole group of absolutely brilliant performers, which we’ll list now but will get back to at a later date: pianists Glenn Gould and Alfred Cortot, the violinist Jacques Thibaud, the conductor Charles Munch and the tenor Fritz Wunderlich.Permalink

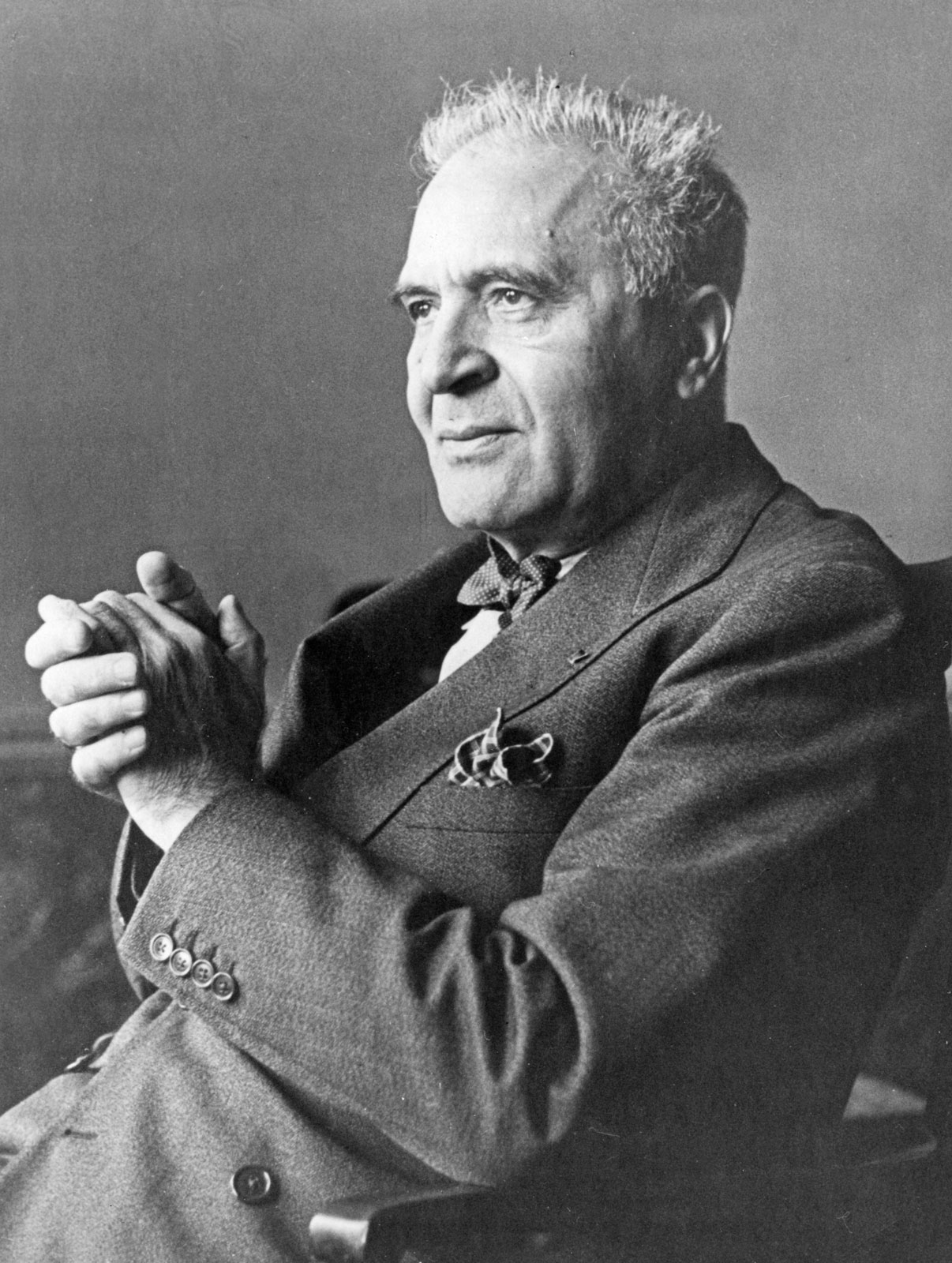

September 16, 2019. Walter. We just missed the birthday of Bruno Walter, one of the greatest conductors of the 20th century. Walter lived a long life: in his youth, he assisted Gustav Mahler, whose work he later helped to establish as the standard orchestral repertory; his last live concert was with Van Cliburn. Few people have influenced the world of music more than him. Walter was born Bruno Schlesinger in Berlin on September 15th of 1876 into a middle-class Jewish family. He initially studied the piano, but, after hearing Hans von Bülow lead an orchestra, decided to switch to conducting. From 1894 to 1896 he worked in Hamburg, assisting Mahler, who was then the chief conductor at the Hamburg State Opera. Mahler’s influence on Walter was enormous, but the composer also valued the talent of his assistant and in 1896 helped him to find a conducting position at the opera theater in Breslau, Silesia (now Wrocław, Poland). The theater director requested that the young conductor changes his name (Schlesinger means “Silesian” in German); eventually, the name Walter was selected. In 1901, after working in several cities, Walter accepted Mahler’s invitation to come to Vienna, were Mahler held the position of the Director of the Hofoper. Walter stayed in Vienna till 1912, two years past Mahler’s death. He gave the premieres of Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde (in 1911) and Ninth Symphony (in 1912). From 1913 till 1922 Walter lived in Munich, were he was appointed the General Music Director. He conducted a lot of Wagner (Bayreuth was suspended during that time) and, in addition to the standard classical repertoire, some contemporary music. During that time, he toured Europe, guest-conducted the Berlin Philharmonic, and made his New York debut. He also conducted at the Salzburg Festival and was appointed the Music Director of Städtische Oper (now, Deutsche Oper) Berlin. His work in Paris and London opera theaters was very well received. From 1929 to 1933 Walter was the conductor of the Gewandhaus Orchestra, Leipzig but he had to resign when the Nazis came to power and returned to Austria. He made a number of excellent recordings with the Vienna Philharmonic (of Mahler and Wagner in particular) and for two years (1936 – 1938) was the music director of the State Opera, the position Mahler held in the 1900s. Walter left Austria after the Anschluss and moved to the United Stated in 1939.

whose work he later helped to establish as the standard orchestral repertory; his last live concert was with Van Cliburn. Few people have influenced the world of music more than him. Walter was born Bruno Schlesinger in Berlin on September 15th of 1876 into a middle-class Jewish family. He initially studied the piano, but, after hearing Hans von Bülow lead an orchestra, decided to switch to conducting. From 1894 to 1896 he worked in Hamburg, assisting Mahler, who was then the chief conductor at the Hamburg State Opera. Mahler’s influence on Walter was enormous, but the composer also valued the talent of his assistant and in 1896 helped him to find a conducting position at the opera theater in Breslau, Silesia (now Wrocław, Poland). The theater director requested that the young conductor changes his name (Schlesinger means “Silesian” in German); eventually, the name Walter was selected. In 1901, after working in several cities, Walter accepted Mahler’s invitation to come to Vienna, were Mahler held the position of the Director of the Hofoper. Walter stayed in Vienna till 1912, two years past Mahler’s death. He gave the premieres of Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde (in 1911) and Ninth Symphony (in 1912). From 1913 till 1922 Walter lived in Munich, were he was appointed the General Music Director. He conducted a lot of Wagner (Bayreuth was suspended during that time) and, in addition to the standard classical repertoire, some contemporary music. During that time, he toured Europe, guest-conducted the Berlin Philharmonic, and made his New York debut. He also conducted at the Salzburg Festival and was appointed the Music Director of Städtische Oper (now, Deutsche Oper) Berlin. His work in Paris and London opera theaters was very well received. From 1929 to 1933 Walter was the conductor of the Gewandhaus Orchestra, Leipzig but he had to resign when the Nazis came to power and returned to Austria. He made a number of excellent recordings with the Vienna Philharmonic (of Mahler and Wagner in particular) and for two years (1936 – 1938) was the music director of the State Opera, the position Mahler held in the 1900s. Walter left Austria after the Anschluss and moved to the United Stated in 1939.

He was already 63 when he arrived in the US. He moved to Beverly Hills, CA, where many German exiles had settled, Schoenber, Klemperer and Thomas Mann among them. He was invited by many major American orchestras, conducting the New York Philharmonic (he was the music director, or “advisor,” as he called it, in 1947-49; he made a number of memorable recordings there), the Chicago Symphony, LA Philharmonic and the Philadelphia Orchestra. In 1941 he made his debut with the Metropolitan Opera and conducted there, occasionally, till 1959. He returned to Europe many times, and made a number of recordings, for example, the excellent Das Lied von der Erde with Kathleen Ferrier and Julius Patzak and the Vienna Philharmonic orchestra. Bruno Walter died in his home in Beverly Hills on February 17th of 1962. Here is a section from one of the last recordings Walter made: Der Abschied (The Farewell), the 6th movement of Das Lied von der Erde. Mildred Miller is the mezzo-soprano, and Ernst Haefliger is the tenor. Bruno Walter conducts the New York Philharmonic; the recording was made in 1960 when Walter was 84. Permalink

September 9, 2019. Rome, by all means, Rome. Again, we’ll miss a week of great anniversaries. Henry Purcell was born 360 years ago; also this week his compatriot, William Boyce, was born. It’s also Arnold Schoenberg’s 145th birthday. The great Italian composer Girolamo Frescobaldi, originally from Ferrara but very successful in Rome (he was appointed the organist of the St. Peter’s basilica) was also born this week. And so were Arvo Pärt and the pianist great Maria Yudina.

September 2, 2019. Ferrara. While in this musical city, once second only to Rome, we’ll miss the anniversaries of a whole group of composers, from Anton Bruckner and Johann Christian Bach to Antonin Dvořák and Darius Milhaud. We’ll have a chance to commemorate them another time.

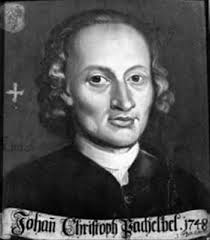

August 26, 2019. Pachelbel and Böhm. Johann Pachelbel was born on September 1st of 1653 in Nuremberg. These days he’s known mostly for his Cannon in D, which is unfair and unfortunate, as Pachelbel was an interesting composer working in many different genres. In one of our previous posts we referred to one of his most important clavier pieces, Hexachordum Apollinis ("Six Strings of Apollo"). “… a set of six arias followed by variations, which, according to Pachelbel himself, could be performed either on the organ or the harpsichord. Variations were a somewhat new musical form in the 17th century, and Hexachordum was by far the most interesting set of variations written to date.” Hexachordum was published in 1699 while Pachelbel was again living in Nuremberg where he moved from Erfurt (in Erfurt he became good friends with Ambrosius Bach, Johann Sebastian’s father; Ambrosius even asked Pachelbel to be the godfather to his daughter Johanna Juditha. Pachelbel also taught music to his son Johann Christoph, who in turn became a music teacher of his younger brother, Johann Sebastian). In Nuremberg Pachelbel was the organist at St. Sebaldus Church, the most important church in the city. He held this position till his death in March of 1706. Pachelbel is noted mostly for his organ works, but he was a wonderful composer of vocal church music as well. Here, for example, is one of his two settings of Magnificat (this one is in D Major). It’s performed by the ensemble Cantus Cölln under the direction of Konrad Junghänel. And speaking of the Magnificat, Pachelbel wrote 60 so called Magnificat Fugues – we’ll talk about them another time.

previous posts we referred to one of his most important clavier pieces, Hexachordum Apollinis ("Six Strings of Apollo"). “… a set of six arias followed by variations, which, according to Pachelbel himself, could be performed either on the organ or the harpsichord. Variations were a somewhat new musical form in the 17th century, and Hexachordum was by far the most interesting set of variations written to date.” Hexachordum was published in 1699 while Pachelbel was again living in Nuremberg where he moved from Erfurt (in Erfurt he became good friends with Ambrosius Bach, Johann Sebastian’s father; Ambrosius even asked Pachelbel to be the godfather to his daughter Johanna Juditha. Pachelbel also taught music to his son Johann Christoph, who in turn became a music teacher of his younger brother, Johann Sebastian). In Nuremberg Pachelbel was the organist at St. Sebaldus Church, the most important church in the city. He held this position till his death in March of 1706. Pachelbel is noted mostly for his organ works, but he was a wonderful composer of vocal church music as well. Here, for example, is one of his two settings of Magnificat (this one is in D Major). It’s performed by the ensemble Cantus Cölln under the direction of Konrad Junghänel. And speaking of the Magnificat, Pachelbel wrote 60 so called Magnificat Fugues – we’ll talk about them another time.

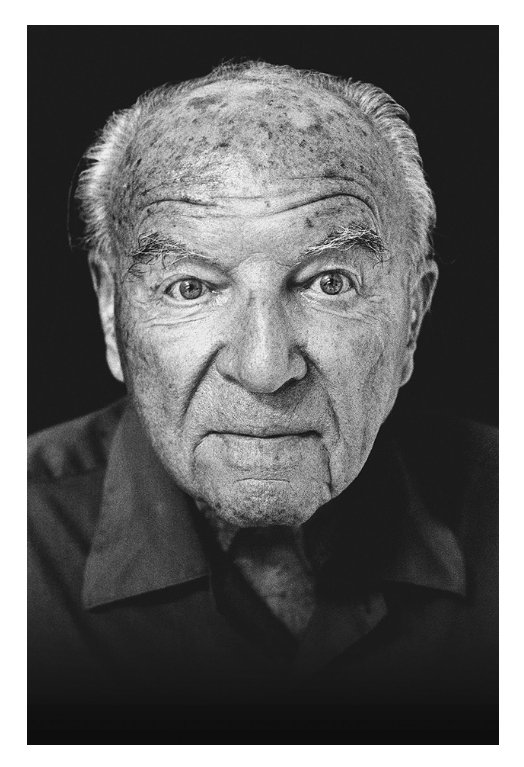

Karl Böhm, one of Austria’s most interesting but controversial conductors, was born on August 28th of 1894 in Graz. He made his conducting debut in 1917 in his hometown; in 1921 Bruno Walter invited him to the Staatsoper in Munich. He stayed there for six years; in 1927 he was invited to lead the opera in Darmstadt. There he performed several modern operas, including Berg’s Wozzeck. After serving in Hamburg he was invited to the Vienna Philharmonic. His 1933 staging of Tristan und Isolde was a huge success. While continuing his engagement in Vienna, one year later Böhm was made the music director of the Dresden Staatsoper. There he replaced Fritz Busch, who was forced to resign by the Nazis. Böhm’s career flourished under the Nazis, even though he never formally joined the Nazi party. He was the director of the Vienna Staatsoper during the last two years of WWII and then led it after the war, when the house was rebuilt. He also had a very successful international career, performing in all major houses of Europe and the US. Böhm made his debut at the Metropolitan Opera in 1957 with Don Giovanni and went on to conduct 262 performances. In 1966, Harold C. Schonberg, The New York Times’s chief music critic, wrote: ''Among the present group of Metropolitan Opera conductors, he towers like a colossus.” Böhm died in Salzburg on August 14th of 1981. He was 87.

Böhm was an enthusiastic and early supporter of the Nazi regime. According to Norman Lebrecht, in 1938 Böhm told the Vienna Philharmonic musicians that anyone who did not vote for Hitler’s Anschluss could not be considered a proper German. He advanced his career as Jewish and German musicians with Jewish ties were forced to leave. In 2015 the Salzburg Festival, itself accused of past anti-Semitism, affixed a plaque in its Karl-Böhm-Saal which states "Böhm was a beneficiary of the Third Reich and used its system to advance his career. His ascent was facilitated by the expulsion of Jewish and politically out-of-favor colleagues.”Permalink

August 19, 2019. Going for the unpopular. Claude Debussy was born this week, on August 22nd of 1782. We love Debussy and he remains one of the most popular composers, both among listeners and performers (in our library we have more than 230 recordings of his works, some pieces are played over and over again). While our listeners have many ways to celebrate Debussy, we will turn to the interesting, but not very popular, composers of the 20th century. Ernst Krenek (pronounced Krzhenek; like Dvorak, pronounced Dvorzhak), Krenek was Czech by birth, and his name originally was spelled Křenek. (The second letter, pronounced Rzh, was replaced with “R” when Krenek moved to the United States). Krenek was born in Vienna, son of a Czech soldier. He studied with the then-famous composer Franz Schreker. During the Great War he was drafted into the Austrian army but spent most of the time in Vienna, continuing his studies. In 1920 he followed Schreker to Berlin where he was introduced to many musicians; there he met Alma Mahler and her daughter Anna (by the time they met, Alma had already divorced her second husband, the architect Walter Gropius and was living with the poet Franz Werfel; Krenek fell in love with Anna and married her in 1924, though their marriage fell apart a few months later). The time in Berlin was very productive: Krenek wrote 18 large-scale pieces between 1921 and 1924. He also worked on parts of Gustav Mahler’s unfinished 10th Symphony but dropped the project as he felt that most of it was too under-developed. In 1925 Krenek traveled to Paris where he met the composers of Les Six; under their influence he decided that his music should be more accessible and wrote a “jazz-opera” Jonny spielt auf(Jonny Plays), which became very popular. Krenek followed with three more one-act operas, one of them, Der Diktator, based on the life of Mussolini. In 1928 Krenek returned to Vienna and became friends with Berg and Webern. He got interested in the 12-tone technique, a form of serialism which attempts to give each of the 12 notes of the scale equal weight. In 1933 he wrote an opera. Karl V, using this technique. It’s premier in Vienna was cancelled (the politics of art, following politics in general at the time, were turning toward things simple and nationalistic) but it was staged in Prague in 1938. Needless to say, it never gained the popularity of Jonny spielt auf. The Nazis labeled Krenek’s music “radical,” things were getting difficult in Austria as well, and soon after the Anschluss Krenek emigrated to the US. He taught in several conservatories and universities and eventually settled in Los Angeles (he moved to Chicago in 1949 to teach at the Chicago Musical College but returned to the West Coast because of the cold winters – and who would blame him). He taught at Darmstadt in early 1950 (Boulez and Stockhausen were among the attendees), continued composing using the serial technique and experimented with electronic music. His last piece was written when Krenek was 88. He died in Palm Springs on December 22nd of 1991. Here’s Krenek’s Piano Sonata no. 2 op. 59 written in 1928. It’s performed by the Russian pianist Maria Yudina. This 1972 recording is unique, as back then “modernist” music wasn’t approved in the Soviet Union. Yudina plays not only Krenek but also Alban Berg’s First piano sonata, the rarely performed “Things in themselves” by Sergei Prokofiev and four pieces by André Jolivet.

listeners and performers (in our library we have more than 230 recordings of his works, some pieces are played over and over again). While our listeners have many ways to celebrate Debussy, we will turn to the interesting, but not very popular, composers of the 20th century. Ernst Krenek (pronounced Krzhenek; like Dvorak, pronounced Dvorzhak), Krenek was Czech by birth, and his name originally was spelled Křenek. (The second letter, pronounced Rzh, was replaced with “R” when Krenek moved to the United States). Krenek was born in Vienna, son of a Czech soldier. He studied with the then-famous composer Franz Schreker. During the Great War he was drafted into the Austrian army but spent most of the time in Vienna, continuing his studies. In 1920 he followed Schreker to Berlin where he was introduced to many musicians; there he met Alma Mahler and her daughter Anna (by the time they met, Alma had already divorced her second husband, the architect Walter Gropius and was living with the poet Franz Werfel; Krenek fell in love with Anna and married her in 1924, though their marriage fell apart a few months later). The time in Berlin was very productive: Krenek wrote 18 large-scale pieces between 1921 and 1924. He also worked on parts of Gustav Mahler’s unfinished 10th Symphony but dropped the project as he felt that most of it was too under-developed. In 1925 Krenek traveled to Paris where he met the composers of Les Six; under their influence he decided that his music should be more accessible and wrote a “jazz-opera” Jonny spielt auf(Jonny Plays), which became very popular. Krenek followed with three more one-act operas, one of them, Der Diktator, based on the life of Mussolini. In 1928 Krenek returned to Vienna and became friends with Berg and Webern. He got interested in the 12-tone technique, a form of serialism which attempts to give each of the 12 notes of the scale equal weight. In 1933 he wrote an opera. Karl V, using this technique. It’s premier in Vienna was cancelled (the politics of art, following politics in general at the time, were turning toward things simple and nationalistic) but it was staged in Prague in 1938. Needless to say, it never gained the popularity of Jonny spielt auf. The Nazis labeled Krenek’s music “radical,” things were getting difficult in Austria as well, and soon after the Anschluss Krenek emigrated to the US. He taught in several conservatories and universities and eventually settled in Los Angeles (he moved to Chicago in 1949 to teach at the Chicago Musical College but returned to the West Coast because of the cold winters – and who would blame him). He taught at Darmstadt in early 1950 (Boulez and Stockhausen were among the attendees), continued composing using the serial technique and experimented with electronic music. His last piece was written when Krenek was 88. He died in Palm Springs on December 22nd of 1991. Here’s Krenek’s Piano Sonata no. 2 op. 59 written in 1928. It’s performed by the Russian pianist Maria Yudina. This 1972 recording is unique, as back then “modernist” music wasn’t approved in the Soviet Union. Yudina plays not only Krenek but also Alban Berg’s First piano sonata, the rarely performed “Things in themselves” by Sergei Prokofiev and four pieces by André Jolivet.

In our library, we have three recordings of Karlheinz Stockhausen. Two of them are rated one note, the lowest rating that could be given. Considering that one piece is played by the pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard, we can safely assume that it’s not the performance that our listeners disliked but the pieces themselves. Stockhausen was born on August 22nd of 1928 and is considered one of the seminal composers of the second half of the 20th century. While we acknowledge the disapproval of some listeners, we think that his music is worth the effort, even if in small doses, and will continue bringing him up on occasion.Permalink