Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

October 22, 2018. Liszt, Berio, Bizet, Paganini, Scarlatti. What a wonderful group! All born this week – that’s why they appear together in this entry – but how different, as if to demonstrate to us, yet again, the enormous breadth of the European musical tradition. Here we have Domenico Scarlatti, a great representative of the Baroque clavichord tradition; Niccolò Paganini, a famous violinist and gifted composer, Franz Liszt, a Romantic composer and legendary pianist: he wrote some of the most exquisite music for the piano (a successor to the harpsichord, Scarlatti’s instrument); Georges Bizet, the French opera composer (Scarlatti’s father, Alessandro, who also wrote operas, wouldn’t have recognized the genre); and finally, Luciano Berio, another Italian, and one of the most interesting composers of the second half of the 20th century. We’ve written about all of them before, so we’ll present each of them with a piece of music.

to us, yet again, the enormous breadth of the European musical tradition. Here we have Domenico Scarlatti, a great representative of the Baroque clavichord tradition; Niccolò Paganini, a famous violinist and gifted composer, Franz Liszt, a Romantic composer and legendary pianist: he wrote some of the most exquisite music for the piano (a successor to the harpsichord, Scarlatti’s instrument); Georges Bizet, the French opera composer (Scarlatti’s father, Alessandro, who also wrote operas, wouldn’t have recognized the genre); and finally, Luciano Berio, another Italian, and one of the most interesting composers of the second half of the 20th century. We’ve written about all of them before, so we’ll present each of them with a piece of music.

Domenico Scarlatti was born on October 26th of 1685, a prodigious year that also gave us Johann Sebastian Bach and George Frideric Handel. Scarlatti wrote 555 keyboard sonatas. Here’s one of them Sonata in B minor, K. 27, L. 449, performed by Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli.

While Scarlatti composed mostly for the harpsichord, Niccolò Paganini (born on October 27th of 1782) wrote much of his music for his favorite instrument, the violin. Here’s the devilishly difficult Caprice No. 3 in octave double stops. It’s performed by Augustin Hadelich, a young Italian violinist of German descent, who won a Grammy in 2016.

Franz Liszt, born on October 22nd of 1811, was for the piano what Paganini was for the violin, and more (he really was a much better composer). In 1838, Liszt wrote Grandes études de Paganini, S.140, a set of six etudes after Paganini’s works; five of the etudes are based on Paganini’s Caprises and one, on the themes from his violin concertos. In 1851 Liszt published a revised version, S. 141, which was, while still formidable, not as demanding technically as the almost unplayable original version. The second one is the version that’s usually played in concerts, but Nikolai Petrov, a wonderful Soviet pianist, made a live recording of the first version. Here’s La Chasse,Étude No. 5 in E major.

Georges Bizet was born on October 25th of 1838. He lived just 37 years and didn’t even witness the success of his major opera, Carmen: Bizet died after the first 33 Paris performances, where the public was more scandalized than amused, while the real triumph was achieved when, within the next several years, Carmen went international. Here’s one of the best Carmens of the 20th century, Elena Obraztsova, in the famous Habanera. The Philharmonia Orchestra is conducted by Giuseppe Patané.

Luciano Berio, the youngest of the group by almost a century, was born on October 24th of 1925. Here’s his 1975 composition called Chemins IV, scored for the oboe and 13 string instruments. It’s based on Berio’s earlier 1969 composition, Sequenza VII. Chemins is performed by Heinz Holliger, oboe, and The London Sinfonietta directed by the composer himself.Permalink

October 15, 2018. Gilels and Flier. Last week we were celebrating the life of Monserrat Caballé, and missed the birthday of one of her stage partners, the incomparable Luciano Pavarotti, who was born on October 12th of 1935 in Modena. We mentioned a recording he made in 1984 with Joan Sutherland and Caballé. Here’s the trio from Act I of Bellini’s Norma: Pavarotti is Pollione, Sutherland, who was 58 at the time of the recording, is Norma and Caballé – Adalgisa.

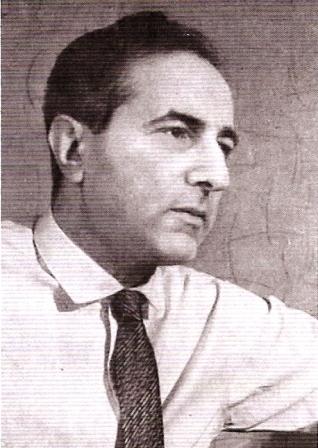

Two great Soviet pianists were also born this week in what was then the Russian Empire: Emil Gilels on October 19th of 1916 and Yakov Flier, on October 21st of 1912. Gilels was born in Odessa (now in Ukraine), Flier – in a small town not far from Moscow. Both were Jewish; with few exception (the rich merchants, the highly educated) Jews were not allowed to live outside of the Pale of Settlement, in the western part of the Empire. How Flier’s parents, a poor family of a watchmaker, managed to live so close to Moscow, isn’t clear.

Gilels, a child prodigy, started his piano studies at the age of five and a half. By the age of 12 he had acquired a considerable repertoire, gave his first recital and was accepted at the Odessa Conservatory. In 1933, at the age of 16, he won the First All-Union Competition of Musicians-Performers. That made him famous and allowed him to perform across the country. In 1935-38 he studied with Heinrich Neuhaus, the famed Moscow Conservatory teacher. By that time Yakov Flier was his main competitor: in 1936 Gilels lost to Flier at the International piano competition in Vienna, where Flier took the first prize, while Gilels took the second, but two years later he had his revenge at the Ysaÿe International Festival in Brussels (after the war this competition would be renamed the Queen Elizabeth): Gilels won and Flier took third place (Moura Lympany came in second). The Second World War put the breakes on Gilels’s international career: he was scheduled to play in the US in 1939 but the tour was canceled. After the war, the great Sviatoslav Richter became his main competitor and eventually overtook him in the Soviet hierarchy, which always needed one person at the top. This had little to do with Gilels’s real achievements: in 1955 he made his US debut, which was highly successful; he played in a trio with Leonid Kogan and Mstislav Rostropovich; he was invited to every major concert hall of Europe. Gilels had a heart attack in 1981 from which he never completely recovered. He died on October 14th of 1985.

Conservatory. In 1933, at the age of 16, he won the First All-Union Competition of Musicians-Performers. That made him famous and allowed him to perform across the country. In 1935-38 he studied with Heinrich Neuhaus, the famed Moscow Conservatory teacher. By that time Yakov Flier was his main competitor: in 1936 Gilels lost to Flier at the International piano competition in Vienna, where Flier took the first prize, while Gilels took the second, but two years later he had his revenge at the Ysaÿe International Festival in Brussels (after the war this competition would be renamed the Queen Elizabeth): Gilels won and Flier took third place (Moura Lympany came in second). The Second World War put the breakes on Gilels’s international career: he was scheduled to play in the US in 1939 but the tour was canceled. After the war, the great Sviatoslav Richter became his main competitor and eventually overtook him in the Soviet hierarchy, which always needed one person at the top. This had little to do with Gilels’s real achievements: in 1955 he made his US debut, which was highly successful; he played in a trio with Leonid Kogan and Mstislav Rostropovich; he was invited to every major concert hall of Europe. Gilels had a heart attack in 1981 from which he never completely recovered. He died on October 14th of 1985.

Yakov Flier was somewhat of a late starter. He studied with the famous Konstantin Igumnov but wasn’t a star at the Conservatory. He graduated in 1934 and only then did his career take off. After several triumphs at international competitions he became as famous as Gilels. His style, though, was very different, more romantic, sometimes verging on exalted, and so was his repertoire, Romantic at the core – Liszt and Chopin were his favorites, together with Rachmaninov (he also played compositions by contemporary Soviet composers, like Prokofiev, Shostakovich and Kabalevsky). Tragically, his career was cut short: around 1945 he developed a problem in his right hand, which progressed; by 1949 he stopped playing recitals. Flier resumed his solo career in 1959-1960; though not as much a virtuoso as before, his playing had by then acquired the depth which he sometimes lacked in his earlier years. Here’s a live recording of Schumann’s Symphonic Etudes Op. 13 made in 1960.

After several triumphs at international competitions he became as famous as Gilels. His style, though, was very different, more romantic, sometimes verging on exalted, and so was his repertoire, Romantic at the core – Liszt and Chopin were his favorites, together with Rachmaninov (he also played compositions by contemporary Soviet composers, like Prokofiev, Shostakovich and Kabalevsky). Tragically, his career was cut short: around 1945 he developed a problem in his right hand, which progressed; by 1949 he stopped playing recitals. Flier resumed his solo career in 1959-1960; though not as much a virtuoso as before, his playing had by then acquired the depth which he sometimes lacked in his earlier years. Here’s a live recording of Schumann’s Symphonic Etudes Op. 13 made in 1960.

A year ago, we wrote two entries about an old photo depicting a group of six young Soviet musicians; Gilels and Flier were among them. You can read them here and here. More on Gilels is here.Permalink

October 8, 2018. Caballé and Verdi. Only three of the 20th century sopranos were ever given affectionate monikers by their adoring fans: “La Divina,” “La Stupenda,” and “La Superba” were indeed the greatest. La Divina – Maria Callas – died years ago, in 1977, she was just 53; La Stupenda – Joan Sutherland – just three years younger than Callas, lived a much longer life, and her singing career was also longer; she died in 2010. We were going to write about Giuseppe Verdi, as his birthday happens to be this week, but on Saturday welearned that La Superba, Monserrat Caballé, had died in Barcelona after a long illness. Caballé was an extraordinary singer. She had a real bel canto technique, a huge vocal diapason that allowed her to sing coloratura arias, and an incomparable repertoire of more than 100 operas. But more than anything else she was known for the purity of her voice and amazing vocal control that allowed her to sustain a long and even pianissimo line.

Stupenda – Joan Sutherland – just three years younger than Callas, lived a much longer life, and her singing career was also longer; she died in 2010. We were going to write about Giuseppe Verdi, as his birthday happens to be this week, but on Saturday welearned that La Superba, Monserrat Caballé, had died in Barcelona after a long illness. Caballé was an extraordinary singer. She had a real bel canto technique, a huge vocal diapason that allowed her to sing coloratura arias, and an incomparable repertoire of more than 100 operas. But more than anything else she was known for the purity of her voice and amazing vocal control that allowed her to sustain a long and even pianissimo line.

Monserrat Caballé was born in Barcelona on April 12th, 1933. She studied at the Barcelona Conservatory and graduated in 1954 with a gold medal. She then moved to Basel, sung in the Basel Opera and then in Bremen. In 1960, she appeared in a small role in La Scala. Her breakthrough came in 1965 when she replaced, on short notice, Marilyn Horne in a New York concert staging of Donizetti’s Lucrezia Borgia. The public didn’t know her, but she earned a 25-minute ovation. That evening launched her to stardom, which stayed with her for the rest of her life. That year, 1965, she made her debut at the Glyndebourne in such diverse roles as Marschallin in Richard Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier and Countess in Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro. Later that year she sung for the first time at the Metropolitan Opera, where she would sing for the next 20 years, appearing on stage 98 times. She went on to conquer every major opera house in the world. She officially premiered at La Scala in 1970, and two years later at London’s Covent Garden and the Lyric Opera in Chicago. In 1974, when La Scala was visiting Moscow, she sung a phenomenal Norma. Bellini’s Norma had a special place in Caballé’s repertoire. She was one of the greatest Normas of all time and recorded it in 1972 with Domingo as Pollione. Twelve years later she made another recording, in which she sung Adalgisa, the role usually sung by a mezzo. In that historic recording, Luciano Pavarotti was Pollione. She partnered with the best tenors of the time, Franco Corelli, Giuseppe Di Stefano and Jose Carreras (and of course with Domingo many times, and Pavarotti).

We mentioned that Caballé had an unusually large repertoire. She sung most of the bel canto roles, the German and French operas, the Spanish zarzuelas, but throughout her career Verdi was in the center. And as we’d still like to celebrate the great Italian, we offer several samples from his operas. Here is D'amor sull'ali rosee, from Il Trovatore. This recording was made in 1974. Orquesta Sinfonica de Barcelona is conducted by Gianfranco Masini. Also in 1974, Caballé recorded Aida. Here’s O Patria mia from Act III. Riccardo Muti leads the New Philharmonia Orchestra. Earlier, in 1968, she recorded this aria from Due Foscari, which isn’t performed very often (RCA Italiana orchestra is under the direction of Antón Guadagno). And finally, from 1971, Ave Maria from Otello. Antón Guadagno again, but this time conducting the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra.Permalink

October 1, 2018. CCCC. It’s easy to remember and, if you’re interested in contemporary music, very much worth checking out. CCCC stands for Chicago Center for Contemporary Composition. The recently established organization will present its inaugural season starting with a concert on October 13th by Yarn/Wire performing music by the Japanese composer Misato Mochizuki, Enno Poppe, a German composer and conductor, and two young Chicagoans. Like most of the season’s concerts it will take place at the University of Chicago’s Logan Center for the Arts, 915 E 60th Street.

a concert on October 13th by Yarn/Wire performing music by the Japanese composer Misato Mochizuki, Enno Poppe, a German composer and conductor, and two young Chicagoans. Like most of the season’s concerts it will take place at the University of Chicago’s Logan Center for the Arts, 915 E 60th Street.

The UChicago has a long tradition of presenting new music, beginning with the Contemporary Chamber Players under Ralph Shapey in 1964 and continuing as Contempo in 2002 under Shulamit Ran and in 2015 under Marta Ptaszyńska. CCCC is led by one of the most interesting contemporary American composers Augusta Read Thomas (here, for example, is her Angel Musings, performed by the Orion Ensemble, and here – Aureole, performed by the DePaul University Symphony, Cliff Colnot conducting). A key component of the Center’s performance series is the newly formed Grossman Ensemble which comprises 13 leading contemporary music specialists. Even the selection of the instruments comprising the ensemble is unusual: a flute,oboe, clarinet, saxophone, horn, two sets of percussion, harp, piano plus the Grammy-nominated Spektral Quartet. The ensemble is co-directed by Ms. Thomas and two other young composers, Anthony Cheung, and Sam Pluta, both from the University’s Music department.

University Symphony, Cliff Colnot conducting). A key component of the Center’s performance series is the newly formed Grossman Ensemble which comprises 13 leading contemporary music specialists. Even the selection of the instruments comprising the ensemble is unusual: a flute,oboe, clarinet, saxophone, horn, two sets of percussion, harp, piano plus the Grammy-nominated Spektral Quartet. The ensemble is co-directed by Ms. Thomas and two other young composers, Anthony Cheung, and Sam Pluta, both from the University’s Music department.

Over the course of the season, the Grossman Ensemble will participate in three performances at the Logan Center for the Arts, all with a focus on the process of creating new work. Eight rehearsals will lead up to each performance, enabling composers to write, workshop, and review new works in close collaboration with the ensemble. The public will be invited to attend an open rehearsal before each concert, allowing them unprecedented access to the creative process. In this inaugural season, the Grossman ensemble will workshop and perform 12 world premieres by University of Chicago faculty, students, and guest composers in the concert season.

In addition to the Grossman Ensemble and Yarn/Wire, Tyshawn Sorey, a composer and performer working at the intersection of classical and jazz music, will play with his trio. And on February 5th of 2019 nine UChicago composers will have a unique occasion to be heard in a performance by the Civic Orchestra of Chicago, a training orchestra for the Chicago Symphony: all of them were asked to create new works to be premiered by this outstanding professional ensemble.

Seven more established composers (“established” being a relative term for a contemporary classical composer) have been commissioned to write new works. They include Steve Lehman, who writes jazz and experimental music (his most recent album was called the #1 Jazz Album of the year by NPR Music and the Los Angeles Times); David Rakowski, a two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist and recipient of many international prizes; Carlos Sanchez-Gutierrez, also a multiple prize-winner; composer and soprano Kate Soper, a Pulitzer Prize finalist whose works have been commissioned by many America orchestras; Chen Yi, known for blending Chinese and Western traditions in her music; and Shulamit Ran (here is her For an Actor: Monologue for Clarinet in a virtuosic performance by Alexander Fiterstein (Clarinet).

We strongly encourage our listeners to give this wonderful undertaking a try.Permalink

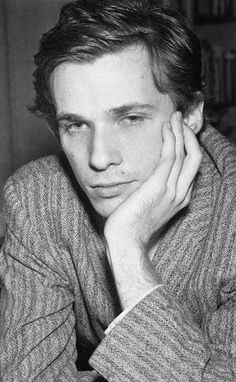

September 24, 2018. On composers and performers. Four composers were born this week, three of them active in the 20th century and one in the 18th. The 20th century composers are: Andrzej Panufnik, a Pole born on this day in 1914; the great Dmitry Shostakovich, born the following day, September 25th, in 1906; and George Gershwin, on September 26th of 1898. The composer from the 18th century is Jean-Philippe Rameau, whose birthday is September 25th of 1683. We still believe in the supremacy of the creative genius over interpretive talent, but several great musicians of the latter category have their anniversaries this week, and we’ve never written about them. First and foremost, is one of the greatest pianists of the 20th century, Glenn Gould. Even though his repertoire was broad, it’s his Bach that we all remember. His phenomenal technique, which allowed him to voice separate lines in the most complex polyphonic compositions, his infallible rhythm, which, in combination with the evenness of his crescendos created such a palpable tension, his phrasing, idiosyncratic but in Bach always perfect, and the incomparable clarity of his sound – all of it created performances that were sensational in the 1950s when he burst on the classical scene and remain equally impressive today. Gould was born in Toronto on September 25th of 1932. He started studying the piano very early. When he was 10, he injured his neck in a fall, and from then on had to use a specially designed chair while playing. He felt comfortable sitting very low, and his teacher, Alberto Guerrero came up with a technique (pulling the notes down, not striking from above) that was be suitable for Gould’s unusual posture. Gould had a phenomenal memory (he remembered not just the piano solos but the orchestral parts as well, and often learned new pieces by reading the music without practicing the piano, taking to the instrument only at the end). Gould made his American debut in 1955 (he played an unusual program of Gibbons, Sweelinck, Bach, Beethoven, Berg, and Webern); Columbian Records signed him the very next day. His first recording was Bach's Goldberg Variations, which became famous overnight. Gould always felt uncomfortable playing in public and in 1964 retired from the stage; after that he played only in the studio. He made a large number of recordings, from the Baroque masters to Haydn and the idiosyncratic late Beethoven, to Brahms, Hindemith, Berg and Schoenberg. And of course, he made numerous recording of his beloved Bach. Out of this vast output, we’ll play just one piece, Bach’s Chromatic Fantasy (here). It was recorded on November 10th of 1979. Gould died in Toronto on October 4th of 1982 at the age of 50.

following day, September 25th, in 1906; and George Gershwin, on September 26th of 1898. The composer from the 18th century is Jean-Philippe Rameau, whose birthday is September 25th of 1683. We still believe in the supremacy of the creative genius over interpretive talent, but several great musicians of the latter category have their anniversaries this week, and we’ve never written about them. First and foremost, is one of the greatest pianists of the 20th century, Glenn Gould. Even though his repertoire was broad, it’s his Bach that we all remember. His phenomenal technique, which allowed him to voice separate lines in the most complex polyphonic compositions, his infallible rhythm, which, in combination with the evenness of his crescendos created such a palpable tension, his phrasing, idiosyncratic but in Bach always perfect, and the incomparable clarity of his sound – all of it created performances that were sensational in the 1950s when he burst on the classical scene and remain equally impressive today. Gould was born in Toronto on September 25th of 1932. He started studying the piano very early. When he was 10, he injured his neck in a fall, and from then on had to use a specially designed chair while playing. He felt comfortable sitting very low, and his teacher, Alberto Guerrero came up with a technique (pulling the notes down, not striking from above) that was be suitable for Gould’s unusual posture. Gould had a phenomenal memory (he remembered not just the piano solos but the orchestral parts as well, and often learned new pieces by reading the music without practicing the piano, taking to the instrument only at the end). Gould made his American debut in 1955 (he played an unusual program of Gibbons, Sweelinck, Bach, Beethoven, Berg, and Webern); Columbian Records signed him the very next day. His first recording was Bach's Goldberg Variations, which became famous overnight. Gould always felt uncomfortable playing in public and in 1964 retired from the stage; after that he played only in the studio. He made a large number of recordings, from the Baroque masters to Haydn and the idiosyncratic late Beethoven, to Brahms, Hindemith, Berg and Schoenberg. And of course, he made numerous recording of his beloved Bach. Out of this vast output, we’ll play just one piece, Bach’s Chromatic Fantasy (here). It was recorded on November 10th of 1979. Gould died in Toronto on October 4th of 1982 at the age of 50.

A pianist from a different era and with very different sensibility, Alfred Cortot was born on September 26th of 1877. His friend the violinist Jacques Thibaud was born three years and one day later, on September 27th of 1880. Both wonderful musicians, we’ll dedicate an entry to them at a later date. And we also cannot forget our favorite, the great German tenor Fritz Wunderlich, who was born on September 26th of 1930 and died after slipping and falling on stairs, 10 days before his 36th birthday. He was one of the greatest Lied singers of all time. Here he’s singing Schubert’s Leise flehen meine Lieder. Hubert Giesen is at the piano. The song was recorded in Minch in July of 1966, less than two months before Wunderlich’s death.Permalink

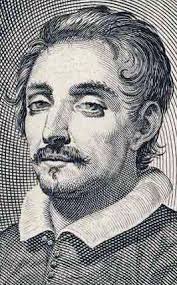

September 17, 2018. Looking back. After the wondrous constellation we had last week, this one looks lacking (hopefully our British readers will forgive us for our lack of enthusiasm regarding Gustav Holst), so we’ll turn to some of the names we had previously only mentioned in passing. One of the most interesting is, without a doubt, Girolamo Frescobaldi (you can read about him here, for example). Frescobaldi was born on September 9th of 1583 in Ferrara, where the active patronage of the Duke Alfonso II created a veritable mecca for musicians. Luzzasco Luzzaschi, a fine composer, was the court organist (and, for a while, Frescobaldi’s teacher), Monteverdi spent several years there, and so did Orlando di Lasso, Carlo Gesualdo and many others. In 1597 Duke Alfonso died, and soon after Ferrara reverted to the papacy; most of the local musicians left for Rome, Frescobaldi among them. For a while he worked as the church organist at Santa Maria in Trastevere, but in 1607 the papal nuncio took him to Flanders. The trip made him known to the public outside of Italy; he also published several new compositions (a volume of madrigals) in Brussels. In July of 1608 Fescobaldi returned to Rome and was made the organist at the important Capella Julia, which performed at the St. Peter’s basilica. He stayed in Rome for the next seven years. As the organist, he wasn’t paid much, so Frescobaldi supplemented his income by teaching and performing in noble houses. Sometime around 1611 he entered the service of Pietro Aldobrandini, a cardinal and a patron of the arts, who was a nephew of Pope Clement VIII and the owner of the magnificent Palazzo Doria Pamphilj. Frescobaldi remained in Aldobrandini’s service till the cardinal’s death in 1621. In 1615 Frescobaldi, being offered a large salary by the duke of Mantua, left the Capella Julia and moved to Mantua. The Duke Ferdinando Gonzaga seems to have liked Frescobaldi’s music, but the rest of the court ignored him, and two months later Frescobaldi decided to return to Rome. There he continued his service at the Aldobrandini household, playing the organ in different Roman churches, and composing. Many of his most important works were written during this period, among them the Capricci and the Second Book of Toccatas, which, in addition to toccatas, included other pieces, such as Canzonas, Gagliardas and other dances, and Magnificats. One of these pieces was a beautiful Passagiato 'Ancidetimi Pur', based on Ancidetemi pur grievi martiri by the Franco-Flemish composer Jacob Arcadelt. Here it is, performed on a harpsichord by Richard Lester. And here is a Toccata from the same Book II, Toccata Nona. This one is played by the harpsichordist Keith Hill.Permalink

for our lack of enthusiasm regarding Gustav Holst), so we’ll turn to some of the names we had previously only mentioned in passing. One of the most interesting is, without a doubt, Girolamo Frescobaldi (you can read about him here, for example). Frescobaldi was born on September 9th of 1583 in Ferrara, where the active patronage of the Duke Alfonso II created a veritable mecca for musicians. Luzzasco Luzzaschi, a fine composer, was the court organist (and, for a while, Frescobaldi’s teacher), Monteverdi spent several years there, and so did Orlando di Lasso, Carlo Gesualdo and many others. In 1597 Duke Alfonso died, and soon after Ferrara reverted to the papacy; most of the local musicians left for Rome, Frescobaldi among them. For a while he worked as the church organist at Santa Maria in Trastevere, but in 1607 the papal nuncio took him to Flanders. The trip made him known to the public outside of Italy; he also published several new compositions (a volume of madrigals) in Brussels. In July of 1608 Fescobaldi returned to Rome and was made the organist at the important Capella Julia, which performed at the St. Peter’s basilica. He stayed in Rome for the next seven years. As the organist, he wasn’t paid much, so Frescobaldi supplemented his income by teaching and performing in noble houses. Sometime around 1611 he entered the service of Pietro Aldobrandini, a cardinal and a patron of the arts, who was a nephew of Pope Clement VIII and the owner of the magnificent Palazzo Doria Pamphilj. Frescobaldi remained in Aldobrandini’s service till the cardinal’s death in 1621. In 1615 Frescobaldi, being offered a large salary by the duke of Mantua, left the Capella Julia and moved to Mantua. The Duke Ferdinando Gonzaga seems to have liked Frescobaldi’s music, but the rest of the court ignored him, and two months later Frescobaldi decided to return to Rome. There he continued his service at the Aldobrandini household, playing the organ in different Roman churches, and composing. Many of his most important works were written during this period, among them the Capricci and the Second Book of Toccatas, which, in addition to toccatas, included other pieces, such as Canzonas, Gagliardas and other dances, and Magnificats. One of these pieces was a beautiful Passagiato 'Ancidetimi Pur', based on Ancidetemi pur grievi martiri by the Franco-Flemish composer Jacob Arcadelt. Here it is, performed on a harpsichord by Richard Lester. And here is a Toccata from the same Book II, Toccata Nona. This one is played by the harpsichordist Keith Hill.Permalink