Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

May 7, 2018. Stamitz, Paisiello and more. The unfortunate coincidence of two birthdays, those of Brahms and Tchaikovsky, the former on this day in 1833, the latter – in 1840, creates a perennial conundrum: how to write about two very important composers of the 19th century, so different as to render any comparison meaningless, both deserving multiple entries. Over the years we’ve tried different tacks, such as here, but this year we’ll simply overlook both and write about several other significant musical figures whose birthdays we usually ignore for the sake of the two masters.

Carl Stamitz was born on May 8th, 1745, in Mannheim. His father, Johann, an important early classical composer and violinist, was appointed to the court of the Electoral Palatinate several years prior and was Carl’s first music teacher. The Elector maintained an orchestra that was famous around Europe; Carl joined it at the age of 17. Among the court musicians there were several composers who are now collectively known as Mannheim School. While not very famous nowadays, these composers, and Carl Stamitz among them, influenced both Franz Joseph Haydn, Mozart, and even the young Beethoven. In 1770 Carl left the orchestra and began a career of a traveling virtuoso: he played violin, viola, and viola d'amore. He traveled all around Europe, playing concerts in Paris, London, Saint Petersburg, and many principalities of Germany. Eventually he moved to Jena, and died there, impoverished, in 1801. Here’s Symphony in D-major "La Chasse" written in 1772. London Mozart Players are conducted by Matthias Bamert.

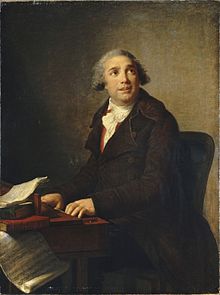

Giovanni Paisiellois one of those composers, who, very popular at their time, are very rarely performed these days. Paisiello was born in a small town of Roccaforzata, in the Taranto province of Apulia on May 9th of 1740. During his long life (he died in Naples on June 5th, 1816) he was a favorite of several monarchs, including Catherine the Great of Russia and Napoleon Bonaparte. Famous for his operas, he contended with such composers as Pergolesi, Cimarosa, and Rossini. When Rossini dared to put to music Le Barbier de Séville, the same Beaumarchais’s play which Paisiello did 30 years earlier, fans of Paisiello created a riot. These days, Rossini’s opera remains one of the most popular in the whole opera repertoire whereas Paisiello’s opera is a rarity. Actually, it’s quite interesting, full of lovely melodies. Here’s proof: the aria Saper bramate, bella il mio nome, from Paisiello’s Il barbiere. Figaro is the wonderful Rolando Panerai, Rosina is sung by the late Graziella Sciutti. Renato Fasano is conducting the Virtuosi di Roma. Stanley Kubrick, the great movie director, also loved this piece: he used it in the gambling scene of his masterpiece, “Barry Lindon.” This puts Paisiello in the company of Handel, Schubert, Bach and Vivbaldi. And one more word on our Rosina: Graziella Sciutti was renowned for her "soubrette" characters. One of her best was Zerlina in the famous recording of Don Giovanni with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Joan Sutherland, Giuseppe Taddei and Piero Cappuccilli. Here she sings Batti, batti, o bel Masetto. The conductor in that production was Carlo Maria Giulini, who was born on May 9th of 1914.

performed these days. Paisiello was born in a small town of Roccaforzata, in the Taranto province of Apulia on May 9th of 1740. During his long life (he died in Naples on June 5th, 1816) he was a favorite of several monarchs, including Catherine the Great of Russia and Napoleon Bonaparte. Famous for his operas, he contended with such composers as Pergolesi, Cimarosa, and Rossini. When Rossini dared to put to music Le Barbier de Séville, the same Beaumarchais’s play which Paisiello did 30 years earlier, fans of Paisiello created a riot. These days, Rossini’s opera remains one of the most popular in the whole opera repertoire whereas Paisiello’s opera is a rarity. Actually, it’s quite interesting, full of lovely melodies. Here’s proof: the aria Saper bramate, bella il mio nome, from Paisiello’s Il barbiere. Figaro is the wonderful Rolando Panerai, Rosina is sung by the late Graziella Sciutti. Renato Fasano is conducting the Virtuosi di Roma. Stanley Kubrick, the great movie director, also loved this piece: he used it in the gambling scene of his masterpiece, “Barry Lindon.” This puts Paisiello in the company of Handel, Schubert, Bach and Vivbaldi. And one more word on our Rosina: Graziella Sciutti was renowned for her "soubrette" characters. One of her best was Zerlina in the famous recording of Don Giovanni with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Joan Sutherland, Giuseppe Taddei and Piero Cappuccilli. Here she sings Batti, batti, o bel Masetto. The conductor in that production was Carlo Maria Giulini, who was born on May 9th of 1914.

Three more composers were also born this week. Anatol Liadov, a Russian miniaturist, and two Belle Époque composers, Jules Massenet, the author of many operas, of which Manon and Werther are probably the most famous, and another Frenchman, Gabriel Fauré. We’ll get back to them another time.Permalink

April 30, 2018. Alessandro Scarlatti and Marcel Dupré. We love Alessandro Scarlatti: he was аcomposer of great talent and these days is clearly underappreciated. Yes, things are changing, and baroque opera is being staged more often. And of course, the great Cecilia Bartoli did much to popularize some of his music, as well as the new generation of counter-tenors, Philippe Jaroussky among them..jpg) Still, we’d like to hear much more of Alessandro’s music, instead of the standard ration dispersed by the classical music radio stations. Alessandro Scarlatti was born in Palermo, on May 2nd of 1660. Here’s what we wrote about him a year ago, so let’s just listen to a couple of his pieces. In addition to operas, Scarlatti wrote a number of oratorios. Musicologists view these oratorios as a substitute for opera; most of Scarlatti’s oratorios were composed in Rome where the Pope was strongly opposed to opera performances. We’ll hear two excerpts from the oratorio Il Sedecia, re di Gerusalemme. It was written in Rome in 1705. Scarlatti was living in Rome since 1702. It was his second visit to the city (he first arrived in Rome at the age of 12 with his family and stayed there for 10 years before moving to Naples). Even though he was under the patronage of Cardinal Ottoboni, Scarlatti wasn’t employed by him directly; instead, he would serve, usually for a short time before being fired, as maestro di cappella at different churches. Eventually Ottoboni made the unhappy Scarlatti one of his “ministers,” but even that didn’t last long as a year later Ottoboni replaced him with Arcangelo Corelli. Operas, Scarlatti’s favorite genre, were virtually prohibited by Pope Clement XI. Scarlatti wrote five operas for Ferdinando de' Medici, then the Grand Prince of Florence but that relationship also ended rather soon, as Ferdinando decided that he likes Giacomo Antonio Perti’s operas better.

Still, we’d like to hear much more of Alessandro’s music, instead of the standard ration dispersed by the classical music radio stations. Alessandro Scarlatti was born in Palermo, on May 2nd of 1660. Here’s what we wrote about him a year ago, so let’s just listen to a couple of his pieces. In addition to operas, Scarlatti wrote a number of oratorios. Musicologists view these oratorios as a substitute for opera; most of Scarlatti’s oratorios were composed in Rome where the Pope was strongly opposed to opera performances. We’ll hear two excerpts from the oratorio Il Sedecia, re di Gerusalemme. It was written in Rome in 1705. Scarlatti was living in Rome since 1702. It was his second visit to the city (he first arrived in Rome at the age of 12 with his family and stayed there for 10 years before moving to Naples). Even though he was under the patronage of Cardinal Ottoboni, Scarlatti wasn’t employed by him directly; instead, he would serve, usually for a short time before being fired, as maestro di cappella at different churches. Eventually Ottoboni made the unhappy Scarlatti one of his “ministers,” but even that didn’t last long as a year later Ottoboni replaced him with Arcangelo Corelli. Operas, Scarlatti’s favorite genre, were virtually prohibited by Pope Clement XI. Scarlatti wrote five operas for Ferdinando de' Medici, then the Grand Prince of Florence but that relationship also ended rather soon, as Ferdinando decided that he likes Giacomo Antonio Perti’s operas better.

In this recording of the duet Caro figlio from Il Sedecia, Anna, the wife of the King Zedekiah (Sedecia), a soprano role, is sung by Virginie Pochon and Ismaele, her son, – by the countertenor Philippe Jaroussky. Notice that his part often lies above the soprano’s. And from the same oratorio, here is Isamele’s aria Caldo sangue, except that in this recording it’s performed by Cecilia Bartoli. Two wonderful, if very different, interpretations.

Marcel Dupré, the French organist and composer, was born on May 3rd of 1886 in Rouen. His father was an organist and a friend of Aristide Cavaillé-Colli, the greatest French organ-maker of the time (organs by Cavaillé-Colli still perform in scores of French churches, starting from the Notre Dame de Paris, Saint-Sulpice, Sainte-Trinité and Sacré-Cœur in Paris to numerous churches and concert halls across Europe and South America, for example, in the Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatory). Dupré entered the Paris Conservatory in 1904, where he studied with famous organ players and composers such Charles-Marie Widor and Louis Vierne. A professor of organ performance at the Paris Conservatory since 1926, in 1934 he succeeded Vidor as the organist at the church of Saint-Sulpice, whose Great Organ is widely considered the best instrument ever built by Cavaillé-Colli. Here’s Dupré’s Prelude and Fugue, Op. 7 no. 3 in G minor. It’s performed byJulian Bewig on a modern instrument, an organ built in 2003 by the firm Fischer & Krämer for the church of St. Marien in Emsdetten, Germany.Permalink

April 23, 2018. Prokofiev. Sergei Prokofiev was born on this day in 1891. Two years ago we celebrated his 125th anniversary and last year we again wrote about him in some detail, so today we’ll focus on some of Prokofiev’s music, especially the piece that so far has been missing from our library. Piano sonata no. 5 is unusual in two respects: it’s the only sonata written outside of Russia, and it’s also the only sonata to have two opus numbers. The first version, op. 38, was composed in 1923. After spending two not very successful years in the US, Prokofiev returned to Europe in 1920. By 1922 he settled in the town of Ettal in the Bavarian Alps (Ettal is a place where the mad King Ludwig II, Wagner’s benefactor, built one of his folly palaces). During that time Prokofiev spent much of his time working on the opera The Fiery Angel, which he had started working on in 1919 and wouldn’t finish till 1927 (the opera was never staged during Prokofiev’s lifetime; the first concert performance took place in 1953 in Paris, the theatrical premier took place in La Fenice, Venice, in 1955). While in Ettal, Prokofiev, a virtuoso pianist, toured many countries, thus earning a living. Also in Ettal, in October of 1923, Prokofiev married the Spanish singer Lina Llubera. Soon after they moved to Paris, and it was there that Prokofiev played the Sonata no. 5 for the first time. The reception was lukewarm, which Prokofiev acknowledged himself. But clearly, he thought better of the music than most listeners and music critics, as he returned to the Sonata in 1952. It’s difficult to imagine more different circumstances: in 1923 Prokofiev, 32 years old and full of energy was free, traveling around Europe, working with Diaghilev, arguing with Stravinsky, about to be married for the first time – and in 1952, only 61 but very ill, he was living in the suburbs of Moscow, suffering official prosecution for “formalism,” with many of his works officially banned, and Lina, his first wife, was arrested and in the Gulag. During his final years Prokofiev composed little new music but concentrated on reworking some of the earlier compositions, his Sonata no. 5, which acquired the new opus number, 135, and Symphony no. 2, which, like the sonata, wasn’t received well on its premier in Paris in 1925. He completed reworking of the piano sonata but never did much work on the Symphony. Prokofiev died on March 5th of 1953, the same day as Stalin. The notice of his death was published two weeks later, so as not to detract people from the main “tragic event.”

and it’s also the only sonata to have two opus numbers. The first version, op. 38, was composed in 1923. After spending two not very successful years in the US, Prokofiev returned to Europe in 1920. By 1922 he settled in the town of Ettal in the Bavarian Alps (Ettal is a place where the mad King Ludwig II, Wagner’s benefactor, built one of his folly palaces). During that time Prokofiev spent much of his time working on the opera The Fiery Angel, which he had started working on in 1919 and wouldn’t finish till 1927 (the opera was never staged during Prokofiev’s lifetime; the first concert performance took place in 1953 in Paris, the theatrical premier took place in La Fenice, Venice, in 1955). While in Ettal, Prokofiev, a virtuoso pianist, toured many countries, thus earning a living. Also in Ettal, in October of 1923, Prokofiev married the Spanish singer Lina Llubera. Soon after they moved to Paris, and it was there that Prokofiev played the Sonata no. 5 for the first time. The reception was lukewarm, which Prokofiev acknowledged himself. But clearly, he thought better of the music than most listeners and music critics, as he returned to the Sonata in 1952. It’s difficult to imagine more different circumstances: in 1923 Prokofiev, 32 years old and full of energy was free, traveling around Europe, working with Diaghilev, arguing with Stravinsky, about to be married for the first time – and in 1952, only 61 but very ill, he was living in the suburbs of Moscow, suffering official prosecution for “formalism,” with many of his works officially banned, and Lina, his first wife, was arrested and in the Gulag. During his final years Prokofiev composed little new music but concentrated on reworking some of the earlier compositions, his Sonata no. 5, which acquired the new opus number, 135, and Symphony no. 2, which, like the sonata, wasn’t received well on its premier in Paris in 1925. He completed reworking of the piano sonata but never did much work on the Symphony. Prokofiev died on March 5th of 1953, the same day as Stalin. The notice of his death was published two weeks later, so as not to detract people from the main “tragic event.”

Here’s the Piano Sonata no. 5 in it’s final edition. It’s performed by Boris Berman (no relation to the great pianist Lazar Berman). Boris Berman was born in Moscow and studied at the Moscow Conservatory with Lev Oborin. He emigrated from the Soviet Union in 1973. Boris Berman is the first pianist to record all of the piano works by Sergey Prokofiev.Permalink

April 16, 2018. . Nikolai Myaskovsky, a Russian composer, was born this week, on April 20th of 1881. Prolific (he wrote 27 symphonies), he was widely performed during his lifetime in the Soviet Union and, to a lesser extent, in Europe and the US. He was often criticized by the Soviet music establishment and almost as often awarded state prizes; these days he’s mostly forgotten. Myaskovsky deserves to be written about, but today we’ll focus on Tomás Luis de Victoria, one of the great composers of the Renaissance, for whom we never have a fixed date as we don’t know when hewas born.

In 1583 Victoria dedicated the second volume of masses (Missarum libri duo) to King Philip II and expressed the desire to return to Spain and lead the life of a priest. His wish was granted: Victoria was named the chaplain to the Dowager Empress María. Empress Maria lived in the Monasterio de las Descalzas Reales. Masses at the convent were served daily, with Victoria acting as the choir master and organist. After dowager’s death in 1603 he remained at the convent in a position endowed by Maria. Victoria was held in very high esteem, was paid very well, and was free to travel. In 1594, he happened to be in Rome when Palestrina died; the funeral mass was celebrated at Saint Peter’s Basilica, with Victoria in attendance. By the end of his own life, Victoria’s music was played all over Europe and even in the New World: his masses were very popular in Mexico and Bogotá. He died on August 20th of 1611 and was buried at the Monasterio de las Descalzas.

Victoria’s masterpiece is Officium Defunctorum, a prayer cycle for the deceased, which includes settings of seven movements of the Funeral Mass and another three pieces. Officium Defunctorum was written on the death of Dowager Empress María in 1603. You can hear all 10 movement of Officium Defunctorum by searching our library. It is performed, with extraordinary clarity and style, by the Spanish ensemble Musica Ficta. Another great interpreter of the music of Victoria is the ensemble The Sixteen, directed by Harry Christophers. Here, in their performance, in Victoria’s Magnificat Sexti Toni, one of the several settings of Magnificat composed by the great Spaniard.Permalink

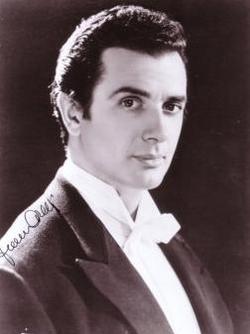

April 9, 2018. Two singers. Franco Corelli’s birthday was yesterday: he was born on April 8th of 1921. One of the greatest tenors of the mid-20th century, he, together with Giuseppe Di Stefano and Mario Del Monaco, brought the level of tenor singing to heights which seem unreachable today. Add to it two supreme sopranos, Maria Callas and Renata Tebaldi, the great baritone Tito Gobbi, the mezzo Giulietta Simionato, the base Cesare Siepi – all of them at the top of their form in the mid-1950s. What a glorious era! Corelli may not have had the most beautiful voice, but the power, clarity, phenomenal breath control and sheer excitement he generated were incomparable. Listen, for example, to this 1955 recording of Cavaradossi’s aria E lucevan le stele from Puccini’s Tosca. One may quibble with the interpretations, with the notes he holds a bit too long – just because he can! – but it’s singing at the very highest level. Or a small sample from the legendary performance of the same opera in the Teatro Regio di Parma on January 21, 1967. Tosca is Virginia Gordoni, Scarpia – Attilio d'Orazi, but it’s Corelli’s 12 seconds of A-sharp in Vittoria, Vittoria at the very end of this two-minute excerpt that brought the theater down. We cut out the ensuing pandemonium (the word “ovation” isn’t strong enough) because it just wouldn’t stop; one couldn’t hear anything anyway, even though the orchestra continued to play (here). Corelli was born in a provincial city of Ancona, his family wasn’t musical, and Franco entered the Pesaro conservatory almost by chance. Even there, he mostly taught himself, following the technique of Mario del Monaco and listening to the old recordings of Caruso, Gigli and Lauri-Volpi. Corelli started singing professionally in 1951; in 1953, in the Rome Opera, he sung Pollione in Bellini's Norma with Maria Callas in the title role. Callas was taken by Corelli’s voice, and in the following years the two sung together on many occasions, especially at La Scala. Corelli also sung with Renata Tebaldi in the famous production of La forza del destino at the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples (YouTube has a large excerpt from it: Mario del Monaco, mentioned in the title, didn’t sing in this particular production). Corelli sung his debut performance at the Metropolitan Opera in 1961 as Manrico in Il Trovatore with Leontine Price. He performed at the Met till 1975, even though in the early 1970s his voice lost some of its luster. In 1976, at the age of 55, Corelli quit. Even though he personally disliked voice teachers, he became one himself, and a very successful one. Franco Corelli died in Milan on October 29th of 2003.

unreachable today. Add to it two supreme sopranos, Maria Callas and Renata Tebaldi, the great baritone Tito Gobbi, the mezzo Giulietta Simionato, the base Cesare Siepi – all of them at the top of their form in the mid-1950s. What a glorious era! Corelli may not have had the most beautiful voice, but the power, clarity, phenomenal breath control and sheer excitement he generated were incomparable. Listen, for example, to this 1955 recording of Cavaradossi’s aria E lucevan le stele from Puccini’s Tosca. One may quibble with the interpretations, with the notes he holds a bit too long – just because he can! – but it’s singing at the very highest level. Or a small sample from the legendary performance of the same opera in the Teatro Regio di Parma on January 21, 1967. Tosca is Virginia Gordoni, Scarpia – Attilio d'Orazi, but it’s Corelli’s 12 seconds of A-sharp in Vittoria, Vittoria at the very end of this two-minute excerpt that brought the theater down. We cut out the ensuing pandemonium (the word “ovation” isn’t strong enough) because it just wouldn’t stop; one couldn’t hear anything anyway, even though the orchestra continued to play (here). Corelli was born in a provincial city of Ancona, his family wasn’t musical, and Franco entered the Pesaro conservatory almost by chance. Even there, he mostly taught himself, following the technique of Mario del Monaco and listening to the old recordings of Caruso, Gigli and Lauri-Volpi. Corelli started singing professionally in 1951; in 1953, in the Rome Opera, he sung Pollione in Bellini's Norma with Maria Callas in the title role. Callas was taken by Corelli’s voice, and in the following years the two sung together on many occasions, especially at La Scala. Corelli also sung with Renata Tebaldi in the famous production of La forza del destino at the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples (YouTube has a large excerpt from it: Mario del Monaco, mentioned in the title, didn’t sing in this particular production). Corelli sung his debut performance at the Metropolitan Opera in 1961 as Manrico in Il Trovatore with Leontine Price. He performed at the Met till 1975, even though in the early 1970s his voice lost some of its luster. In 1976, at the age of 55, Corelli quit. Even though he personally disliked voice teachers, he became one himself, and a very successful one. Franco Corelli died in Milan on October 29th of 2003.

Montserrat Caballé, one of the greatest sopranos of the second half of the 20th century, will turn 85 in three days. Caballé was born on April 12th of 1933 in Barcelona. A real bel canto soprano (unlike most of the sopranos on stage today), she was one of the best Normas ever. She also excelled in Donizetti, especially as Mary Queen of Scots in Maria Stuarda and Elizabeth I in Roberto Devereaux. She also sung in many Verdi operas. Caballé had her debut at the Metropolitan Opera in 1965 in a not very typical role of Marguerite in Gounod’s Faust. Since then she has performed at the Met dozens of times, singing in several Verdi operas, Puccini's Turandot and operas by Donizetti. Her official debut in La Scala happened only in 1970, when she was already world-famous. She often partnered with the much younger José Carreras (while at the same time Joan Sutherland took under her wing a younger Luciano Pavarotti). There are hundreds of great recording of Caballé’s art; here is an excerpt from Roberto Devereu. The live recording was made in Venice in 1972. Bruno Bartoletti conducts the orchestra of the Teatro la Fenice.Permalink

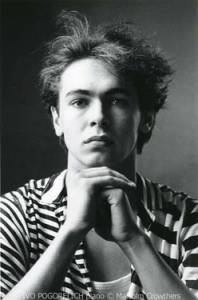

April 3, 2018. Haydn, Pogorelich. We’d like to come back to Joseph Haydn, whom we mentioned, rather perfunctorily, last week. As we were looking for a sample of Richter’s recording of a Haydn sonata (Richter made several and played Haydn often) we came across one made by Ivo Pogorelich in 1991. It was a recording of a wonderful Piano Sonata no. 30 in D major, Hoboken XVI:19, composed in 1767. Pogorelich, born in Belgrade, is one of the most unusual pianists of his generation. His career began with a scandal: in 1980 the jury of the Chopin International Competition eliminated him after the second round. Martha Argerich resigned in protest (she was not the only one to object, so did Nikita Magaloff and Paul Badura-Skoda, although they didn’t quit). The publicity generated by the Warsaw scandal helped Pogorelich’s career. While some of his interpretations were eccentric, they were not outlandish, on top of which he had a flawless technique. In 1981 Pogorelich was invited to the Carnegie Hall (he played there many times; his 1992 performance of Balakirev’s Islamey became legendary). That same year, 1981, he debuted in London, and a year later he was signed by Deutsche Grammophon. Pogorelich had studied in the Soviet Union since 1976; the year of the Chopin Competition he married his teacher, Alisa Kezheradze, 21 years his senior. Little is known about Kezheradze. When she met Pogorelich, she was married to a Soviet functionary, living in a large apartment in the center of Moscow. She taught piano at the Music department of the Pedagogic Institute (Vladimir Genis, a Russian-German composer and pianist who studied there, remembers Kezheradze as “the only bright spot in that theater of the absurd, … striking, slim, of indeterminate age, with a face of a Georgian princess.” She also worked with several Conservatory students. One of them was the young Mikhail Pletnev, whom Kezheradze prepared for the 1978 Tchaikovsky Competition after the death of Pletnev’s professor, Yakov Flier, six months earlier. Pletnev went on to win the competition. By then Kezheradze had already divorced her first husband. Her and Ivos’ marriage application was first rejected, but later the authorities relented, allowing them to marry and emigrate. Kezheradze and Pogorelich moved to Europe where they lived together till her death of liver cancer in 1996. Pogorelich, devastated by the loss, practically abandoned the concert stage. When, some years later, he resumed his public career, the eccentricities of his earlier years developed into interpretations that were often incomprehensible. He took the tempos so slow that the whole musical structure fell apart (for example, his recording of Chopin’s Nocturne op. 48, no. 1 takes an insane but mesmerizing nine minutes and ten seconds. Arthur Rubinstein plays it, stately, in a 5:47). He’d play either pianissimo or fortissimo, with strange accents. Anthony Tommasini of the New York Time finished his 2006 review of a Carnegie Hall concert thusly: "Here is an immense talent gone tragically astray. What went wrong?" It’s impossible to answer this question, but there are many of Pogorelich’s recordings that could be enjoyed today. The Hob. XVI:19 is one of them. Every one of Haydn’s musical ideas is brilliantly enunciated, every line is clear, the sound is beautiful, everything is balanced – a great performance overall. Listen to it here.Permalink

Pogorelich in 1991. It was a recording of a wonderful Piano Sonata no. 30 in D major, Hoboken XVI:19, composed in 1767. Pogorelich, born in Belgrade, is one of the most unusual pianists of his generation. His career began with a scandal: in 1980 the jury of the Chopin International Competition eliminated him after the second round. Martha Argerich resigned in protest (she was not the only one to object, so did Nikita Magaloff and Paul Badura-Skoda, although they didn’t quit). The publicity generated by the Warsaw scandal helped Pogorelich’s career. While some of his interpretations were eccentric, they were not outlandish, on top of which he had a flawless technique. In 1981 Pogorelich was invited to the Carnegie Hall (he played there many times; his 1992 performance of Balakirev’s Islamey became legendary). That same year, 1981, he debuted in London, and a year later he was signed by Deutsche Grammophon. Pogorelich had studied in the Soviet Union since 1976; the year of the Chopin Competition he married his teacher, Alisa Kezheradze, 21 years his senior. Little is known about Kezheradze. When she met Pogorelich, she was married to a Soviet functionary, living in a large apartment in the center of Moscow. She taught piano at the Music department of the Pedagogic Institute (Vladimir Genis, a Russian-German composer and pianist who studied there, remembers Kezheradze as “the only bright spot in that theater of the absurd, … striking, slim, of indeterminate age, with a face of a Georgian princess.” She also worked with several Conservatory students. One of them was the young Mikhail Pletnev, whom Kezheradze prepared for the 1978 Tchaikovsky Competition after the death of Pletnev’s professor, Yakov Flier, six months earlier. Pletnev went on to win the competition. By then Kezheradze had already divorced her first husband. Her and Ivos’ marriage application was first rejected, but later the authorities relented, allowing them to marry and emigrate. Kezheradze and Pogorelich moved to Europe where they lived together till her death of liver cancer in 1996. Pogorelich, devastated by the loss, practically abandoned the concert stage. When, some years later, he resumed his public career, the eccentricities of his earlier years developed into interpretations that were often incomprehensible. He took the tempos so slow that the whole musical structure fell apart (for example, his recording of Chopin’s Nocturne op. 48, no. 1 takes an insane but mesmerizing nine minutes and ten seconds. Arthur Rubinstein plays it, stately, in a 5:47). He’d play either pianissimo or fortissimo, with strange accents. Anthony Tommasini of the New York Time finished his 2006 review of a Carnegie Hall concert thusly: "Here is an immense talent gone tragically astray. What went wrong?" It’s impossible to answer this question, but there are many of Pogorelich’s recordings that could be enjoyed today. The Hob. XVI:19 is one of them. Every one of Haydn’s musical ideas is brilliantly enunciated, every line is clear, the sound is beautiful, everything is balanced – a great performance overall. Listen to it here.Permalink