Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

April 8, 2019. Giuseppe Tartini was born on this day in 1692 in Pirano, Republic of Venice (now Piran, Slovenia). He studied at the university of Padua, where it seems he spent most of his time on fencing. In 1710, he married one Elisabetta Premazore, a woman two years his elder who, unfortunately for Tartini, was a favorite of the local bishop, Cardinal Giorgio Cornaro. The Cardinal accused Tartini of abducting Elisabetta, and, to avoid prosecution, Tartini fled to the monastery of San Francesco in Assisi. There he started playing the violin, amazingly late for a future virtuoso. He left the monastery around 1714, played for a while with the Ancona opera orchestra, and heard the famous Francesco Veracini perform in Venice. That episode affected him greatly, as he felt that his playing was inferior. He spent the next two years practicing, greatly improving his skills. In 1721 he was made Maestro di Cappella at the famous Basilica di Sant'Antonio in Padua. In 1723, in a midst of another scandal (Tartini was accused of fathering an illegitimate child) he left for Prague, where he stayed for three years under the auspices of the Kinskys, a noble Czech family. He returned to Padua in 1726 and organized a violin school, probably the most famous one of its time. Students came to the “school of the nations” from all of Europe. Around the same time Tartini published his first volume of compositions containing violin sonatas and concertos. He continued to compose through the years, although later in his life he concentrated more on theoretical works. He continued to live in Padua and died there on February 26th of 1770.

on fencing. In 1710, he married one Elisabetta Premazore, a woman two years his elder who, unfortunately for Tartini, was a favorite of the local bishop, Cardinal Giorgio Cornaro. The Cardinal accused Tartini of abducting Elisabetta, and, to avoid prosecution, Tartini fled to the monastery of San Francesco in Assisi. There he started playing the violin, amazingly late for a future virtuoso. He left the monastery around 1714, played for a while with the Ancona opera orchestra, and heard the famous Francesco Veracini perform in Venice. That episode affected him greatly, as he felt that his playing was inferior. He spent the next two years practicing, greatly improving his skills. In 1721 he was made Maestro di Cappella at the famous Basilica di Sant'Antonio in Padua. In 1723, in a midst of another scandal (Tartini was accused of fathering an illegitimate child) he left for Prague, where he stayed for three years under the auspices of the Kinskys, a noble Czech family. He returned to Padua in 1726 and organized a violin school, probably the most famous one of its time. Students came to the “school of the nations” from all of Europe. Around the same time Tartini published his first volume of compositions containing violin sonatas and concertos. He continued to compose through the years, although later in his life he concentrated more on theoretical works. He continued to live in Padua and died there on February 26th of 1770.

Tartini owned several Stradivari violins, one of which he passed on to his student Salvini, who in turn gave it to the Polish virtuoso violinist Karol Lipiński. As the story goes, sometime around 1817, in Milan, the young Lipiński played for Salvini. After the performance was over, Salvini asked for Lipiński’s violin and, to Lipiński’s horror, smashed it to pieces. He then handed the dumbstruck Lipiński a different violin and said that it is “a gift from me, and, simultaneously, as a commemoration of Tartini.” That was one of Tartini’s Stradivari, one of the best violins the master ever made; it is now known as the “Lipinski Stradivari.” The story of the violin almost ended in tragedy: some time ago, an anonymous donor lent it to Frank Almond, the concertmaster of the Milwaukee Symphony orchestra; on January 27th of 2014, after a concert, Almond was attacked by a stun gun and the violin was stolen. An international recovery effort was immediately organized, and one week later, the suspects, a man and a woman, were arrested. The violin was recovered three days later.

Here’s Tartini’s best known piece, the famous Devil’s Trills sonata. Itzhak Perlman is at his best (in 1977); Samuel Sanders is on the piano.

One of the greatest tenors of the 20th century, Franco Corelli, was also born on this day in 1921 in Ancona, where Tartini played in an orchestra after leaving the Assisi monastery. Corelli had the voice of incomparable beauty, remarkable power and clarity. Even though Corelli had several voice teachers, he mostly taught himself, imitating great singers of the past. He made his operatic debut in 1951 in Spoleto, singing José in Carmen. From 1954 to 1965 he sang at La Scala. In 1957 he made a sensational debut in the Covent Garden as Cavaradossi. In 1961 he appeared at the Met for the first time, singing Manrico in Il Trovatore (Leonora was Leontine Price). For the following decade, he sung in New York every year, appearing 282 times in 18 different roles. Here is the thrilling aria A te, o cara from the first act of Bellini’s I puritani. Franco Ferraris conducts the Philharmonia Orchestra.Permalink

April 1, 2019. Three pianists were born on this day. We usually talk about Sergei Rachmaninov as a composer, but he was also one of the greatest pianists of the 20th century. Josef Hofmann, himself a superlative pianist to whom Rachmaninov dedicated his Third Piano Concerto, joked that he would gladly swap his fingers for Rachmaninov’s and would add his toes to boot (there’s some truth to the joke: Hofmann’s hands were of average size, while Rachmaninov had huge hands that allowed him to easily play the most difficult chords). Contemporaries compared Rachmaninov to Liszt and Anton Rubinstein. He was a supreme virtuoso who never showed off, being concerned with the structure and the overall line of a composition. Rachmaninov was an expressive pianist with a beautiful sound (Arthur Rubinstein raved about his tone), and his rhythm was freer than what we’re used to these days, but when we listen to his recordings, the playing sounds felicitous to the composer’s intent. Rachmaninov often played his own compositions, both his numerous piano miniatures and concertos. Rachmaninov made many recordings, the earliest – in 1919, for Edison Records. He also made a number of recording rolls, many of them for the American Piano Company (Ampico). Rachmaninov, initially skeptical of the quality of the recordings, said, after listening to a reproduced piano roll: "Gentlemen – I, Sergei Rachmaninov, have just heard myself play!" Here is an example, Rachmaninov “performing” his own Prelude in G minor, op. 23, no. 5. The piano roll was digitized and then played on a Bösendorfer 290 SE Reproducing Piano.

Josef Hofmann, himself a superlative pianist to whom Rachmaninov dedicated his Third Piano Concerto, joked that he would gladly swap his fingers for Rachmaninov’s and would add his toes to boot (there’s some truth to the joke: Hofmann’s hands were of average size, while Rachmaninov had huge hands that allowed him to easily play the most difficult chords). Contemporaries compared Rachmaninov to Liszt and Anton Rubinstein. He was a supreme virtuoso who never showed off, being concerned with the structure and the overall line of a composition. Rachmaninov was an expressive pianist with a beautiful sound (Arthur Rubinstein raved about his tone), and his rhythm was freer than what we’re used to these days, but when we listen to his recordings, the playing sounds felicitous to the composer’s intent. Rachmaninov often played his own compositions, both his numerous piano miniatures and concertos. Rachmaninov made many recordings, the earliest – in 1919, for Edison Records. He also made a number of recording rolls, many of them for the American Piano Company (Ampico). Rachmaninov, initially skeptical of the quality of the recordings, said, after listening to a reproduced piano roll: "Gentlemen – I, Sergei Rachmaninov, have just heard myself play!" Here is an example, Rachmaninov “performing” his own Prelude in G minor, op. 23, no. 5. The piano roll was digitized and then played on a Bösendorfer 290 SE Reproducing Piano.

A very different pianist, Dinu Lipatti, was born on this day in 1917 in Bucharest. He studied at the local conservatory where he was awarded prizes as a pianist and composer. In 1934 he participated in the Vienna piano competition and was awarded the second prize. Alfred Cortot, who felt that Lipatti deserved to win, resigned from the jury and invited the young pianist to study with him in Paris. Lipatti joined Cortot’s piano class and also studied the composition with Paul Dukas and Nadia Boulanger. Lipatti’s performance career didn’t start till 1939 but soon after was interrupted with the beginning of WWII. In 1943, with the help of the Swiss pianist Edwin Fischer, Lipatti emigrated to Switzerland and joined the conservatory in Geneva. It was around that time that his illness showed itself for the first time. It took doctors four years to diagnose it as Hodgkin's disease. (By an incredibly tragic coincidence, around the same time another talented pianist, Rosa Tamarkina, was also diagnosed with the same disease. Both continued to perform, even as their health declined. Both gave their last concerts and died in 1950, Lipatti at the age of 33, Tamarkina – even younger, just 30.) In 1946 Lipatti signed a contract with Columbia Records and made several recordings at his home in Geneva. During his last concert, given in September 1950 in Besançon he played Bach’s First Partita, Mozart’s A minor Sonata, two Schubert impromptus and the complete Chopin waltzes, except no.2, in A Flat, op. 34, no. 1, which he was too exhausted to play. Instead he played Myra Hess’s transcription of Bach’s Jesu, joy of man’s desiring as a last-minute substitution. Here’s Jesu in a recording made in 1947 in London. And here is Chopin’s Waltz in A Flat, op. 34, no. 2, the one he was too tired to perform during his last concert.

We’d like to note that today is the 75th anniversary of a wonderful Soviet-Russian-Ukrainian-Jewish-German pianist, Vladimir Krainev. He studied with Heinrich Neuhaus, won the Tchaikovsky competition in 1970, performed all over the world, and created an international foundation in support of young pianists. Krainev died in Hannover, Germany, on April 29th of 2011.Permalink

The person whom we really wanted to write about this week is the conductor Willem Mengelberg. Of a Dutch-German artistic family (his father was a well-known sculptor), Mengelberg was born in Utrecht on March 28th of 1871. After studying the piano and organ in his native city, he went to the Cologne Conservatory, where he also studied composition. In 1895, at the age of 24, he was appointed the principal conductor of the Concertgebouw Orchestra, and, during his tenure of 50 years, made it into one of the best European orchestras. Mengelberg met Gustav Mahler in Vienna in 1902 and invited the composer to Amsterdam to conduct one of his symphonies; Mahler did that in 1903, performing his Third Symphony. Then, in 1904, also at the Concertgebouw, and following Mengelberg’s suggestion, Mahler conducted his Fourth Symphony – twice during one concert, once before the break, and then again, in the second half! What a great idea, to play a complex composition, new to listeners’ ear, two times, so that it settles in one’s mind, becomes more understandable. This would’ve never happened in our time. Mengelberg and the Concertgebouw developed a tradition of playing Mahler, one of the strongest in Europe (the Austrians and the Germans weren’t big on Mahler at that time). In 1920, Mengelberg instituted a Mahler Festival. His tempos and rubatos sound a bit outdated, and the recording quality is not very good, but you may still enjoy his interpretations. Here, from 1939, is Mahler’s Symphony no. 4.Permalink

The person whom we really wanted to write about this week is the conductor Willem Mengelberg. Of a Dutch-German artistic family (his father was a well-known sculptor), Mengelberg was born in Utrecht on March 28th of 1871. After studying the piano and organ in his native city, he went to the Cologne Conservatory, where he also studied composition. In 1895, at the age of 24, he was appointed the principal conductor of the Concertgebouw Orchestra, and, during his tenure of 50 years, made it into one of the best European orchestras. Mengelberg met Gustav Mahler in Vienna in 1902 and invited the composer to Amsterdam to conduct one of his symphonies; Mahler did that in 1903, performing his Third Symphony. Then, in 1904, also at the Concertgebouw, and following Mengelberg’s suggestion, Mahler conducted his Fourth Symphony – twice during one concert, once before the break, and then again, in the second half! What a great idea, to play a complex composition, new to listeners’ ear, two times, so that it settles in one’s mind, becomes more understandable. This would’ve never happened in our time. Mengelberg and the Concertgebouw developed a tradition of playing Mahler, one of the strongest in Europe (the Austrians and the Germans weren’t big on Mahler at that time). In 1920, Mengelberg instituted a Mahler Festival. His tempos and rubatos sound a bit outdated, and the recording quality is not very good, but you may still enjoy his interpretations. Here, from 1939, is Mahler’s Symphony no. 4.Permalink

March 25, 2019. Composers, performers… This is another overabundant week. Franz Joseph Haydn was born on March 31st of 1732. And one of the most important composers of the first half of the 20th century, Béla Bartók, was born on this day, March 25th of 1881. The second half of the last century is also represented, by none other than Pierre Boulez, born on March 26th of 1925. And then there are two composers from previous eras: the 18th century Johann Adolph Hasse, born 320 years ago, on March 25th of 1699, whose opere serie were, for a while, some of the most popular in all of Europe – that, given that among his competitors were the young Handel and still very active Italians of the older generation, from Alessandro Scarlatti to Petri, Bononcini, Caldara, and Porpora. And from two centuries earlier, one of the most important composers of the Spanish Renaissance, Antonio de Cabezón, who was born on March 30th of 1510. (We’ve written about all them several times, for example here, here, here, and here).

And then there are two eminent pianists, Wilhelm Backhaus and Rudolf Serkin. Backhaus was born on March 26th of 1884 in Leipzig, Serkin – on March 28th of 1903 in Eger, a town in Bohemia now called Cheb. Both immensely talented, both great interpreters of the music of Beethoven, both native German speakers, both spent a lot of time in the US, but it’s hard to imagine more different biographies. Backhaus was close to the Nazis and knew Hitler personally, though eventually he emigrated from Nazi Germany to Switzerland. Serkin, of Russian-Jewish decent, lived in Vienna and then in Berlin, but after the rise of Nazism had to flee Germany first to Switzerland then to the US. We’ll write about both and compare some of their recordings.

That’s not all: Mstislav Rostropovich, one of the greatest cellists of the 20th century, was also born this week – on March 27th of 1927, in Baku, the capital of now-independent Azerbaijan. Not just a phenomenal cellist, he was also a conductor and, at the time when all civic activity was suppressed, an active supporter of the banned writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn. For that the Soviets punished Rostropovich, canceling all his foreign tours. In 1974, thanks to Senator Edward Kennedy and active Western public opinion, Rostropovich and his wife, the soprano Galina Vishnevskaya, were allowed to leave the Soviet Union; they returned only after the fall of the Communist regime in 1991. Rostropovich is another brilliant musician on our “to do” list. And as if that wasn’t enough, Arturo Toscanini, who needs no introduction, was born on this day in 1867 in Parma.

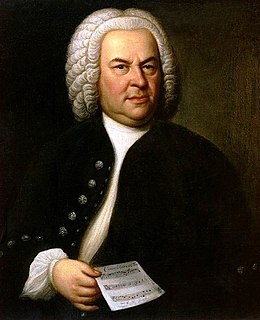

March 18, 2019. Johann Sebastian Bach was born on March 21st of 1685. Last year, while celebrating his birthday, we focused on the period of mid-1730s, when Bach was living in Leipzig and was involved with Collegium Musicum, an association of professional musicians and students, which was created by Telemann in 1702 for the purpose of producing regular public concerts. During Bach’s tenure, the summer concerts took place on Wednesdays between 4 and 6 p.m. in the coffee-garden “near the Grimmisches Thor (gates)”; during the winter time – on Fridays between 8 and 10 p.m. in Zimmermann’s coffee-house. Many of Bach’s works were performed during these concerts, some old and some new. The famous Harpsichord Concerto in D minor, BWV 1052 was one of them, and so were the other six concertos, BWV 1053 through BWV 1058. Also performed were his orchestral suites, violin concertos and other pieces. He played the music of other composers as well, and, according to his son, C.P.E. Bach, all famous musicians passing through Leipzig played for him.

students, which was created by Telemann in 1702 for the purpose of producing regular public concerts. During Bach’s tenure, the summer concerts took place on Wednesdays between 4 and 6 p.m. in the coffee-garden “near the Grimmisches Thor (gates)”; during the winter time – on Fridays between 8 and 10 p.m. in Zimmermann’s coffee-house. Many of Bach’s works were performed during these concerts, some old and some new. The famous Harpsichord Concerto in D minor, BWV 1052 was one of them, and so were the other six concertos, BWV 1053 through BWV 1058. Also performed were his orchestral suites, violin concertos and other pieces. He played the music of other composers as well, and, according to his son, C.P.E. Bach, all famous musicians passing through Leipzig played for him.

Going back to the harpsichord concertos: while they sound original, most of their music had been written by Bach earlier. For example, here is the first movement of the Harpsichord Concerto no. 1, BWV 1052, the recording made live by Glenn Gould in 1957 in Leningrad during his historic tour of the Soviet Union (the Leningrad Academic Symphony Orchestra is conducted by Ladislav Slovák). And here is the first movement, Sinfonia, of Bach’s Cantata BWV 146, Wir müssen durch viel Trübsal (We must [pass] through great sadness), composed either in 1726 or 1728. As you can hear, it’s the same music but arranged for a slightly different orchestra, with the keyboard being the organ rather than the harpsichord. The very dynamic organist in the Sinfonia is Howard Moody, the British composer and keyboard player. John Eliot Gardiner conducts the Monteverdi Choir and English Baroque Soloists. The second movement of the concerto was taken from the second movement of the same BWV 146 cantata, except that in this case Bach had to work harder, as converting a choral line to keyboard was not such a straightforward task. Here’s movement II, Adagio, from the concerto, and here – the second movement from the Wir müssen durch viel Trübsal cantata. The third movement of the concerto was also taken from an earlier-written cantata, but in this case, from the first movement of the cantata BWV 188, Ich habe meine Zuversicht (I have [placed] my confidence). Here’s the final movement of the Concerto, and here – the first movement of the Cantata Ich habe meine Zuversicht. We should be grateful to Bach for so brilliantly recycling the old material; he couldn’t have expected that in the 20th century his keyboard concertos would become so popular, and of course he could’ve never predicted the phenomenon of Glenn Gould, but whether fair or not, his concertos are played and recorded much more often than the cantatas.

If you wish to listen to the complete pieces, you could do so by searching our library, or clicking here for the Harpsichord Concerto no. 1, BWV 1052, here – for the Cantata BWV 146, Wir müssen durch viel Trübsal, and here – for the Cantata BWN 188, Ich habe meine Zuversicht.

Nikolai Rinsky-Korsakov, Modest Mussorgsky, and Franz Schreker, an interesting but almost forgotten Austrian composer active at the end of the 19th – first third of the 20th century were also born this week. We’ll get to them another time.Permalink

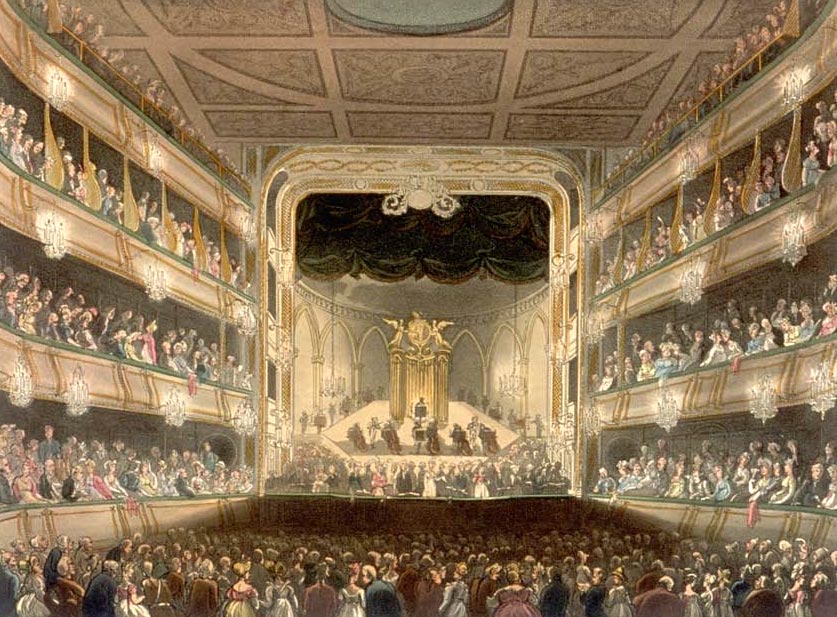

March 11, 2019. Ariodante and Telemann. Just two weeks ago we celebrated Handel’s birthday, and a couple days ago we had a chance to listen to (and, unfortunately, watch) his masterpiece, the opera Ariodante, presented by the Lyric Opera of Chicago. At about 3 hours of pure music (four hours with intermissions) it’s a bit long, but it was written when the public didn’t consider an opera performance a semi-religious event to be experienced in motionless silence – this attitude was acquired a century later – and mingled, talked, played cards and enjoyed themselves as much as they could. Were Handel to write it today, he’d probably cut about a quarter of it out, but even as is, with too many repeats, the music is absolutely gorgeous. The libretto is absurd, but most of the operas then (and since then) had silly storylines.. The characters, all with Italian names and singing in Italian, are placed somewhere in Scotland where two lovers, a prince and king’s daughter, are almost driven to death and madness by a villainous duke, but of course everything ends well: the duke is punished, and the lover happily marry. The premier took place at the Covent Garden; it was the first opera ever staged in the newly-built theater. The role of protagonist, prince Ariodante, was sung by the famous castrato Carestini, who replaced Senesino, for many years Handel’s favorite, after they parted ways and Senesino joined the competing Opera of the Nobility. The bad Duke Polinesso was sung by a contralto, Maria Caterina Negri. At the Lyric, the genders were reversed: Ariodante was sung by a mezzo, while Polinesso – by a countertenor. Both were wonderful. Alice Coote, a prominent interpreter of Handel’s music, needed some time to warm up, but her famous Act II aria, Scherza infida, was superb (here it is in the performance by the countertenor David Daniels, which probably sounds closer to what Handel had in mind). Iestyn Davies was wonderful as Polinesso: his voice is not very big, but it is very focused, projects well and has a remarkable agility. The rest of the cast was excellent.

pure music (four hours with intermissions) it’s a bit long, but it was written when the public didn’t consider an opera performance a semi-religious event to be experienced in motionless silence – this attitude was acquired a century later – and mingled, talked, played cards and enjoyed themselves as much as they could. Were Handel to write it today, he’d probably cut about a quarter of it out, but even as is, with too many repeats, the music is absolutely gorgeous. The libretto is absurd, but most of the operas then (and since then) had silly storylines.. The characters, all with Italian names and singing in Italian, are placed somewhere in Scotland where two lovers, a prince and king’s daughter, are almost driven to death and madness by a villainous duke, but of course everything ends well: the duke is punished, and the lover happily marry. The premier took place at the Covent Garden; it was the first opera ever staged in the newly-built theater. The role of protagonist, prince Ariodante, was sung by the famous castrato Carestini, who replaced Senesino, for many years Handel’s favorite, after they parted ways and Senesino joined the competing Opera of the Nobility. The bad Duke Polinesso was sung by a contralto, Maria Caterina Negri. At the Lyric, the genders were reversed: Ariodante was sung by a mezzo, while Polinesso – by a countertenor. Both were wonderful. Alice Coote, a prominent interpreter of Handel’s music, needed some time to warm up, but her famous Act II aria, Scherza infida, was superb (here it is in the performance by the countertenor David Daniels, which probably sounds closer to what Handel had in mind). Iestyn Davies was wonderful as Polinesso: his voice is not very big, but it is very focused, projects well and has a remarkable agility. The rest of the cast was excellent.

Unfortunately, the production, shared by the Lyric with the Festival d'Aix-en-Provence, the Canadian Opera Company, and Dutch National Opera in Amsterdam, was unattractive, silly and in parts, offensive. Placed into a religion-obsessed 1960s Scottish village, it turns the story into a morality play with Polinesso as a rapist-priest and Ginerva, the princess, a victim who rebels, quite awkwardly, at the very end of the opera. Visually boring, its only interesting feature was skillful puppetry which replaced Handel’s ballet numbers. In the absurd finale, while Handel’s glorious music celebrates the marriage of Ariodante and Ginerva, the princess slips away unnoticed and hitches a ride, presumably into a better future. But in the end, this production was just an unfortunate distraction from an otherwise hugely rewarding musical experience.

Georg Philipp Telemann was born on March 14th of 1681. Four years older than Handel (and Bach), he was friends with both. Telemann first met Handel in Halle in 1701 (Handel was only 16 but had already composed several Church cantatas, now lost). In his later years Telemann took up gardening, then in vogue, and received exotic plants from Handel. While in Hamburg, Telemann conducted several of Handel’s operas and even wrote additional music for some of them. And, like Handel, he wrote a piece called Water Music. Not as famous as Handel’s, it still is a marvelous piece. Here it’s performed by the Zefiro Baroque Orchestra.Permalink

March 4, 2019. Plethora. Nine composers and a conductor were born this week. The farthest removed from us, but still sounding unorthodox and fresh is Carlo Gesualdo, a great composer, a nobleman and a murderer. Prince of Venosa, he was born in that southern Italian city on March 8th of 1566 (you can read more about this fascinating person here). His music is quite remarkable in its use of chromaticism, as you can hear in this recording of Itene, o miei sospiri, a madrigal from Book V, published in 1611. It’s performed by the Italian ensemble Delitiae Musicae under the direction of Marco Longhini.

nobleman and a murderer. Prince of Venosa, he was born in that southern Italian city on March 8th of 1566 (you can read more about this fascinating person here). His music is quite remarkable in its use of chromaticism, as you can hear in this recording of Itene, o miei sospiri, a madrigal from Book V, published in 1611. It’s performed by the Italian ensemble Delitiae Musicae under the direction of Marco Longhini.

Antonio Vivaldi was born more than 100 years later, on March 4th of 1678. While Gesualdo’s music bridges the late Renaissance with the early Baroque, Vivaldi was writing when the Italian Baroque was at its peak. We know him best for his concertos (the Four Seasons being by far the most popular), but he also wrote church music, as, for example, this Canta in prato, from Introduzione al Dixit. The Scottish soprano Margaret Marshall and the English Chamber Orchestra are conducted by Vittorio Negri.

In addition to the two above, five more composers were born in Europe: Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach on March 8th of 1714, Josef Mysliveček – on March 9th of 1737, Pablo de Sarasate – on March 10th of 1844, Maurice Ravel – on March 7th of 1875, and Arthur Honegger – on March 10th of 1892. CPE Bach and Mysliveček were fine representatives of the early Classical period; Sarasate was a Romantic, Ravel – an Impressionist, and Honegger – a member of Les Six, who were both influenced by and rejected Impressionism. By the end of the 19th century European classical music tradition spread over the American continents, and two of our composers were born there: Heitor Villa-Lobos, in Brazil, on March 5th of 1887, and Samuel Barber, in the US, on March 9th of 1910.

From Gesualdo to Barber – that’s a wonderful arc, and we could play hours of great music by these composers, but we’d like to celebrate a different milestone: Bernard Haitink will turn 90 today, March 4th. We had the pleasure of hearing him conduct the Chicago Symphony on many occasions; his interpretations of Mahler are superb, only Pierre Boulez (whose approach was very differen) could reach the same level of musicianship with his award-winning version of the Ninth Symphony. Haitink was born in Amsterdam. As a child he studied the violin; he joined the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra as a violinist. Soon after he started conducting with that orchestra and at the age of 27 became its principal conductor. In 1956 he got a chance to conduct the great Concertgebouw Orchestra, when Carlo Maria Giulini became indisposed and Haitink was asked to step in (Cherubini's Requiem was in the program). The concert went very well and soon Haitink was made a guest conductor. In 1961 he became Concertgebouw’s youngest ever principal conductor, a position he shared for two years with the famous German, Eugen Jochum; in 1963 Jochum left and Haitink remained as the only principal conductor. While at the Concertgebouw, in 1967, he became involved with the London Philharmonic Orchestra (there, he was also the principal conductor); he worked and toured with both. Haitink was a prolific opera conductor: in 1977 he became the musical director of the Glyndebourne Festival; he also worked at the Metropolitan Opera and the Covent Garden. With the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, he video-recorded the full Ring cycle. In 2006 Haitink was made the principal conductor of the Chicago Symphony and later was offered the position of the music director but declined citing his age. Here’s the Finale, of Mahler’s Symphony no. 6 (Allegro moderato - Allegro energico). The Chicago Symphony Orchestra is conducted by Bernard Haitink.Permalink