Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

July 11, 2016. Bononcini. Giovanni Bononcini was born this week, on July 18th of 1670, in Modena. At the zenith of his career he was one of the most famous composers in Europe and George Frideric Handel’s competitor. Bononcini was a son of composer and theorist Giovanni Maria Bononcini. Giovanni Maria died in and Giovanni moved to Bologna, where he continued his musical education and wrote his first compositions. By the age of 15 he published three collections of music, and three years later composed a mass. In 1691 Bononcini went to Rome and entered the service of Filippo Colonna (Colonna, a scion of one of the most colorful Italian families, with many ducal and princely titles to the name, was also a great-nephew of Cardinal Mazarin). A man of letters and a member of the Accademia degli Arcadi, Colonna had in his employ Silvio Stampiglia, a famous librettist. Together, Bononcini and Stampiglia wrote ten operas. Their opera Xerse became a huge success. Here’s the aria Ombra mai fu from Bononcini’s Xerse. We all know Handel’s magnificent Ombra mai fu (here) from his opera of the same name. When you listen to Bononcini, you’ll recognize the Handel, and not by chance: Handel used Bononcini’s aria for his own setting. Clearly, intellectual property was not as sacrosanct in the 17th and 18th centuries as it is now. It turns out that this particular “borrowing” has an even longer history, because Bononcini wasn’t the first. He actually used the music of Francesco Cavalli, who wrote his own Xerse in 1654. The opera contained an aria, Ombra mai fu (“Never was a shade...”), which became very popular. Here’s the “original” (Cavalli) version. The libretto for Cavalli’s opera was written by Nicolò Minato; it was reused by both Bononcini and Handel. Bononcini’s version is performed by the German soprano Simone Kermes (she’s wonderful in the Baroque repertory – listen to her in Alessandro Scarlatti’s Cara tomba, from Il Mitridate Eupatore). The Cavalli is sung by the Belgian counter-tenor Rene Jacobs, who also conducts the performance. The Handel is performed by the great mezzo, Cecilia Bartoli.

George Frideric Handel’s competitor. Bononcini was a son of composer and theorist Giovanni Maria Bononcini. Giovanni Maria died in and Giovanni moved to Bologna, where he continued his musical education and wrote his first compositions. By the age of 15 he published three collections of music, and three years later composed a mass. In 1691 Bononcini went to Rome and entered the service of Filippo Colonna (Colonna, a scion of one of the most colorful Italian families, with many ducal and princely titles to the name, was also a great-nephew of Cardinal Mazarin). A man of letters and a member of the Accademia degli Arcadi, Colonna had in his employ Silvio Stampiglia, a famous librettist. Together, Bononcini and Stampiglia wrote ten operas. Their opera Xerse became a huge success. Here’s the aria Ombra mai fu from Bononcini’s Xerse. We all know Handel’s magnificent Ombra mai fu (here) from his opera of the same name. When you listen to Bononcini, you’ll recognize the Handel, and not by chance: Handel used Bononcini’s aria for his own setting. Clearly, intellectual property was not as sacrosanct in the 17th and 18th centuries as it is now. It turns out that this particular “borrowing” has an even longer history, because Bononcini wasn’t the first. He actually used the music of Francesco Cavalli, who wrote his own Xerse in 1654. The opera contained an aria, Ombra mai fu (“Never was a shade...”), which became very popular. Here’s the “original” (Cavalli) version. The libretto for Cavalli’s opera was written by Nicolò Minato; it was reused by both Bononcini and Handel. Bononcini’s version is performed by the German soprano Simone Kermes (she’s wonderful in the Baroque repertory – listen to her in Alessandro Scarlatti’s Cara tomba, from Il Mitridate Eupatore). The Cavalli is sung by the Belgian counter-tenor Rene Jacobs, who also conducts the performance. The Handel is performed by the great mezzo, Cecilia Bartoli.

While in Rome, Bononcini became a member of the important musical Accademia di Santa Cecilia, and was also invited to join the Arcadian Academy. Following the death of Filippo’s wife in 1697, Bononcini left Rome for Vienna, where he was invited to the court of the Emperor Leopold I. He stayed in Vienna for five years and then moved to Berlin on the invitation of Queen Sophia Charlotte, the wife of Frederick I of Prussia. Around 1715 Bononcini returned to Rome. His opera Camilla was highly successful and was staged not just in Italy but also in London. That’s where he went in 1720. Handel was the king of opera, but the first several seasons were highly successful for Bononcini. Three quarters of all performances given by the Royal Academy of Music were of Bononcini’s music. That, unfortunately, changed as the Jacobite risings made Bononcini, a Catholic, politically unacceptable. He considered leaving London but the Duchess of Marlborough offered him a stipend of £500 a year for life, so he stayed. An unfortunate affair followed in 1731. A friend of Bononcini’s, composer Maurice Greene introduced a manuscript of a madrigal, which he claimed to be written by Bononcini. The madrigal turned out to be by Antonio Lotti. This was too much even in the era of free borrowing. Greene was forced to quit the Academy of Ancient Music, and Bononcini had to leave London. He went to France. He continued moving from one European capital to another until settling in Vienna in 1737, where the Empress Maria Theresa provided him with a small pension. There he stayed till his death in 1747.

Compared to Handel, it is obvious that Bononcini’s talent was on a smaller scale and more conservative. Still, his melodic gifts were amazing. Just listen to the aria Per la gloria d’adorarvi from his opera Griselda (it doesn’t hurt that it’s performed by Luciano Pavarotti).Permalink

July 4, 2016. Mahler, Symphony no. 4. Gustav Mahler was born on July 7th of 1860, and to celebrate his birthday we will again turn to one of his symphonies, this time the Fourth. Mahler started working on the Fourth Symphony in 1899. By then he had moved from Hamburg to Vienna, having received the appointment to the Vienna Hofoper (the Court opera theater) in 1897. To be even considered for the position, he had to convert to Catholicism: as liberal as the Emperor Franz Joseph was, to have a Jewish conductor of the main opera was unthinkable. Mahler, an agnostic, had no qualms: the ceremony took place on February 23, 1997. In April he started as the Kapellmeister and in September of the same year Mahler was promoted to director. He understood that his position would not be easy: much of the Viennese public and a good number of music critics were anti-Semitic, and didn’t care about Mahler’s conversion. One of the leaders of the anti-Semitic camp was the very popular mayor, Karl Lueger, who also founded the Austrian Christian Socialist party, a precursor of the German National-Socialists (Lueger was a very efficient administrator, and is credited with transforming Vienna into a modern city; still, the fact that a monument to him still stands in the center of Vienna in a square called Doktor-Karl-Lueger-Paltz is inconceivable). In financial terms, Mahler’s life became quite comfortable. He rented a large apartment on Auengruggergasse, number 2, a building next to the Belvedere Gardens (it was designed by Otto Wagner, the leading Art Nouveau architect).

By then he had moved from Hamburg to Vienna, having received the appointment to the Vienna Hofoper (the Court opera theater) in 1897. To be even considered for the position, he had to convert to Catholicism: as liberal as the Emperor Franz Joseph was, to have a Jewish conductor of the main opera was unthinkable. Mahler, an agnostic, had no qualms: the ceremony took place on February 23, 1997. In April he started as the Kapellmeister and in September of the same year Mahler was promoted to director. He understood that his position would not be easy: much of the Viennese public and a good number of music critics were anti-Semitic, and didn’t care about Mahler’s conversion. One of the leaders of the anti-Semitic camp was the very popular mayor, Karl Lueger, who also founded the Austrian Christian Socialist party, a precursor of the German National-Socialists (Lueger was a very efficient administrator, and is credited with transforming Vienna into a modern city; still, the fact that a monument to him still stands in the center of Vienna in a square called Doktor-Karl-Lueger-Paltz is inconceivable). In financial terms, Mahler’s life became quite comfortable. He rented a large apartment on Auengruggergasse, number 2, a building next to the Belvedere Gardens (it was designed by Otto Wagner, the leading Art Nouveau architect).

For the first two years in Vienna Mahler was so involved with the Opera that there was no time for him to compose. A perfectionist, he rehearsed every production for many weeks at a time and was very demanding, overseeing all aspects of every production. That didn’t endear him to the singers and the orchestra. On the other hand, the repertory and the quality of the opera house improved dramatically. The first opera to be staged under Mahler’s direction was Wagner’s Lohengrin; Mozart‘s Die Zauberflöte followed. Both were a huge success. Mahler also took over the subscription concerts of the Philharmonic, which were previously lead by the famous conductor Hans Richter. There were days when he conducted a symphony concert during the day and an opera in the evening. The workload was enormous and stressful. He was also affected by the plight of his close friend Hugo Wolf, who, suffering from the late stages of syphilis, fell into dementia and was sent to an asylum. With a long concert and opera season fully consumed by directing and conducting, the summer months became very important to Mahler as the time to unwind and, more importantly, to compose. In the summer of 1899 Mahler rented a summer-house in Steinbach on lake Altaussee, not far from Salzburg. A fashionable resort, it was frequented by writers and journalists, such as Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Theodor Herzl. It wasn’t his first visit to Steinbach: there he composed parts of the Second and Third Symphonies. He even built a “composing hut” there, to seclude himself from the summer crowd. It was in Steinbach that Mahler started working on his Fourth Symphony. The pattern – conducting and directing during Vienna’s musical season and composing during the summer months – was firmly established the next year, when Mahler decided to go to the village of Maiernigg on lake Wörthersee in Carinthia. Eventually he would build a small hut there as well so that he could compose without being interrupted. The Fourth Symphony was completed that summer. It’s the last of the so-called Wunderhorn symphonies: every one of the first four incorporates some music from the Des Knaben Wunderhorn collection, Mahler’s setting of German folk poems. In the case of the Fourth symphony, it’s the song, "Das himmlische Leben" (“The Heavenly Life”), originally written in 1892, that Mahler re-orchestrated into the fourth movement of the symphony. Here it is, with Claudio Abbado conducting “Mahler’s own” Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra; Frederica von Stade is the mezzo soprano.Permalink

June 27, 2016. Four Klavierstücke, op. 119 by Brahms. Below is an article by Joseph DuBose about the last set Johannes Brahms ever wrote for piano solo. We illustrate it with performances by Alon Goldstein and Matthew Graybil. ♫

The 4 Klavierstücke, op. 119 is the last of Brahms’s compositions for his own instrument. While it is true that the 51 Übungen were published later , these exercises were nevertheless compiled over several years from works already written. In the wake of the E-flat minor Intermezzo that closed the op. 118, the current collection opens with two similarly introspective minor key intermezzi. The first, in B minor, passes by with resigned melancholy and a cool detachment that aptly follows such a heart-wrenching expression of emotion. The following E minor Intermezzo, on the other hand, builds out of a nervous energy, and by its conclusion begins to turn towards a brighter mood. The C major Intermezzo that follows abounds with rhythmic energy, and quite fittingly sets the stage from the robust and dynamic E-flat major Rhapsodie. An appropriate end for Brahms’s solo piano music, the Rhapsodie abounds with the virile energy of the early Rhapsodies while also looking back at times to the op. 10 Ballades.

, these exercises were nevertheless compiled over several years from works already written. In the wake of the E-flat minor Intermezzo that closed the op. 118, the current collection opens with two similarly introspective minor key intermezzi. The first, in B minor, passes by with resigned melancholy and a cool detachment that aptly follows such a heart-wrenching expression of emotion. The following E minor Intermezzo, on the other hand, builds out of a nervous energy, and by its conclusion begins to turn towards a brighter mood. The C major Intermezzo that follows abounds with rhythmic energy, and quite fittingly sets the stage from the robust and dynamic E-flat major Rhapsodie. An appropriate end for Brahms’s solo piano music, the Rhapsodie abounds with the virile energy of the early Rhapsodies while also looking back at times to the op. 10 Ballades.

The B minor Intermezzo (here) makes the most direct use of the descending thirds motif since the Caprice in D minor that opened op. 116. Whereas in the Caprice the thirds were used to great effect both melodically and contrapuntally, the effect here is entirely harmonic. As the thirds descend, the tones overlap resulting in beautiful, impressionistic chords of the ninth and eleventh that place the music in a twilit area between the keys of B minor and D major. Atop these luscious harmonies, a melancholy tune more suggestive of D major until its final cadence, floats across the hazy harmonic landscape. While this principal melody comes to a close on a definitive half cadence in B minor, a firm assertion of the tonic is avoided by the immediate appearance of a secondary theme unmistakably in the key of D major. This new theme struggles to give voice to the inner turmoil of the piece, as it builds fervently over chromatically rising harmonies into a forte that inevitably melts away over dominant seventh chords obscured by two chromatic lines moving in contrary motion. The melody starts again, though now altered, and builds more quickly into a more fulfilling climax on the dominant, reinforced by rippling triplets in the bass. A moment of resignation is then reached as the music begins to die away with poignant sighs that fall from the upper register into the bass. Like a fog rolling in, obscuring everything within its reach, the descending thirds return in a four measure transition that brings about a slightly embellished reprise of the opening. A brief coda, built on the plaintive sighs heard earlier, begins to reaffirm the D major tonality. However, just prior to the expected cadence it gives way to a final chain of thirds that spans across all the tones of a thirteenth chord before resolving into a final B minor chord (continue reading here).Permalink

June 20, 2016. The brothers Marcello. Benedetto Marcello was born on June 24th of 1686 in Venice. Of a noble family, he was a younger brother of Alessandro, also a composer. Benedetto followed in Alessandro’s steps, becoming a member of the Grand Council of Venice at the age of 20. Their father wanted Marcello to study law and Benedetto obliged. In 1711 he became a member of the Council of Forty, the government of Venice. In 1730 he was sent as a governor to Pula, Istria, then a territory of the Venetian Republic, now part of Croatia. Eight years later he returned to Italy, in rather poor health, and was hired by the city of Brescia as chief financial officer. He died a year later, in 1739, of tuberculosis.

age of 20. Their father wanted Marcello to study law and Benedetto obliged. In 1711 he became a member of the Council of Forty, the government of Venice. In 1730 he was sent as a governor to Pula, Istria, then a territory of the Venetian Republic, now part of Croatia. Eight years later he returned to Italy, in rather poor health, and was hired by the city of Brescia as chief financial officer. He died a year later, in 1739, of tuberculosis.

Benedetto studied music from an early age; among his teachers was Francesco Gasparini, a well-known composer and teacher (Johann Sebastian Bach was familiar with Gasparini’s compositions). Though a prolific composer, he never held a musical appointment, which put him in a different category compared to professional musicians: in Italy there was a clear social separation between “maestri” and “dilettanti.” That didn’t stop him from being one of the most influential composers of his time. One of Benedetto’s major works was the setting of psalms he called “Estro-poetico armonico.” It was published in eight volumes between 1724 and 1726. Here’s one of the psalms, Mentre io tutta ripongo in Dio, a setting for four voices. It’s performed by the ensemble Cantus Cölln, Konrad Junghänel conducting and playing the lute. In 1731, when he was in Pula, he wrote an oratorio Il piano e il riso delle quattro stagioni dell'anno (Lamentation and Joy of the Four Seasons of the Year). Here’s a Symphony from the oratorio. It’s performed by I Virtuosi delle Muse under the direction of Stefano Molardi.

Some sources say that Alessandro Marcello was born on February 1st, 1673, others have his birthday almost four years earlier, on August 24th, 1669. The latter is more likely, co nsidering that he was admitted to the Grand Council of Venice in 1690: it’s much more probable that he became a member at the age of 21 rather than 17. Highly educated and a man of varied interests, he served as ambassador, was a prolific writer, for a short time indulged in painting and was a talented composer. Alessandro was a member of the prestigious Accademia degli Animosi, the Venetian branch of the Roman Accademia degli Arcadi. He also collected musical instruments, which are now exhibited in Rome, in the National museum of musical instruments. Alessandro wrote a number of cantatas, and also an Oboe concerto, which is often attributed to his brother Benedetto. Johann Sebastian Bach liked it so much that he transcribed it for the harpsichord; in the catalogue of Bach’s works it has number BWV 974. Here’s the original, from Alessandro Marcello. The soloist is Paolo Grazzi, Andrea Marcon is leading the Venice Baroque Orchestra.Permalink

nsidering that he was admitted to the Grand Council of Venice in 1690: it’s much more probable that he became a member at the age of 21 rather than 17. Highly educated and a man of varied interests, he served as ambassador, was a prolific writer, for a short time indulged in painting and was a talented composer. Alessandro was a member of the prestigious Accademia degli Animosi, the Venetian branch of the Roman Accademia degli Arcadi. He also collected musical instruments, which are now exhibited in Rome, in the National museum of musical instruments. Alessandro wrote a number of cantatas, and also an Oboe concerto, which is often attributed to his brother Benedetto. Johann Sebastian Bach liked it so much that he transcribed it for the harpsichord; in the catalogue of Bach’s works it has number BWV 974. Here’s the original, from Alessandro Marcello. The soloist is Paolo Grazzi, Andrea Marcon is leading the Venice Baroque Orchestra.Permalink

June 13, 2016. Gounod, Stravinsky and a Stamitz. Charles Gounod and Igor Stravinsky were born this week, and also Johann Stamitz (père), a Czech-German composer, and the popular Norwegian, Edvard Grieg. Johann Stamitz had two sons, Carl and Anton, Carl being probably the better known of the three, but Johann’s talent shouldn’t be underrated. He was born Jan Václav Stamic (he Germanized the name later in his life) on June 18th or 19th of 1717 in a small town in Bohemia. After studying at the University of Prague he embarked on a career of violin virtuoso. Sometime around 1741 Stamitz was hired by the Mannheim court, which at the time had one of the best orchestras in Germany. Stamitz started as a violinist, then was promoted to the position of Concertmaster and eventually the music director. Stamitz’s responsibilities were to compose orchestral music and conduct; under him the orchestra developed into the most famous ensemble in the world. Some years later the 18-year old Mozart would marvel at their precision and technique. In 1754 Stamitz traveled to Paris and stayed there for a year. In Paris he performed at the Concert Spirituel, the first public concert series in history (the performances took place at the Tuileries Palace, which was burned down during the days of the Paris Commune in 1871). Stamitz returned to Mannheim in the fall of 1755. He died less than two years later at the age of 39. Stamitz composed 58 symphonies and is considered the founding father of the “Mannheim School” of composition, which influenced many composers, including Haydn and Mozart. Here’s one of his symphonies, in A major "Frühling" (“Spring”). Virtuosi di Praga are conducted by Oldřich Vlček.

Jan Václav Stamic (he Germanized the name later in his life) on June 18th or 19th of 1717 in a small town in Bohemia. After studying at the University of Prague he embarked on a career of violin virtuoso. Sometime around 1741 Stamitz was hired by the Mannheim court, which at the time had one of the best orchestras in Germany. Stamitz started as a violinist, then was promoted to the position of Concertmaster and eventually the music director. Stamitz’s responsibilities were to compose orchestral music and conduct; under him the orchestra developed into the most famous ensemble in the world. Some years later the 18-year old Mozart would marvel at their precision and technique. In 1754 Stamitz traveled to Paris and stayed there for a year. In Paris he performed at the Concert Spirituel, the first public concert series in history (the performances took place at the Tuileries Palace, which was burned down during the days of the Paris Commune in 1871). Stamitz returned to Mannheim in the fall of 1755. He died less than two years later at the age of 39. Stamitz composed 58 symphonies and is considered the founding father of the “Mannheim School” of composition, which influenced many composers, including Haydn and Mozart. Here’s one of his symphonies, in A major "Frühling" (“Spring”). Virtuosi di Praga are conducted by Oldřich Vlček.

Charles Gounod was born on June 17th of 1818. He’s rightfully famous for his opera Faust, but he also composed 11 other operas, though none of them at the level of Faust. One of the first operas, Sapho from 1851, was written for his friend, soprano Pauline Viardo, who had recently triumphed in Meyerbeer’s Le prophète. The opera wasn’t successful commercially, but established Gounod as one of the leading young composers. Sapho isn’t staged often these days but some arias are lovely. Here’s the aria Ô ma lyre immortelle in the performance by the wonderful French singer, a soprano-turned-mezzo, Régine Crespin. And of course Je veux vivre from Roméo et Juliette remains popular to this day. Here it is sung by another French singer, the soprano Natalie Dessay.

Also on June 17th but of 1882 Igor Stravinsky was born. We celebrate him every year, and mention him more often than any other composer of the 20th century. Last year we explored Le Baiser de la Fée, his ballet from 1927, commissioned by Ida Rubinstein. At the same time Stravinsky was working on another ballet, Apollo (or Apollon musagète). The commission came from an unusual source, the US Library of Congress. In 1928, Apollo was choreographed first by Adolph Bolm (Ruth Page was one of the muses); that production was quickly forgotten. The same year, the 24-year-old George Balanchine, working for Diagilev’s Ballets Russe, staged Apollo in Paris; the costumes were designed by Coco Chanel, Stravinsky conducted. Apollo became one of his most popular neoclassical pieces. Here it is, performed by the London Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Robert Craft. Robert Craft, a writer and conductor who died a half a year ago, on November 10th of 2015, was one of the people closest to Stravinsky. He recorded practically all of Stravinsky’s orchestral music and wrote several books about the composer, including Conversations with Igor Stravinsky.

Permalink

June 6, 2016. Queen Christina, Part II. Christina left Sweden in the summer of 1654; she was 27 years old. She converted to the Catholic faith while in Brussels, and the event was celebrated several weeks later in Innsbruck, under the auspice of Archduke Ferdinand. The festivities, which lasted a whole week, included a performance of L’Argia, an opera by a then very popular composer, Antonio Cesti. Christina’s journey to Rome, with a large entourage and accompanied by cardinals, felt like a triumphal procession. She arrived in Rome just before Christmas of 1655; the Pope Alexander VII received her as if she were a reigning Queen: a royal convert from Protestantism to Catholicism was a big catch for the Papacy. Festivities followed Christina’s arrival, and operas, still new as a genre and very popular in Rome, were at the center: Marco Marazzoli’s Vita humana, dedicated to Christina, an opera by Antonio Tenaglia, and Historia di Abraham et Isaac by Giacomo Carissimi. The staging venues were private palazzos: Palazzo Barberini and Palazzo Pamphilj – as there were no public opera theaters in Rome at the time, those were for Christina to establish.

which lasted a whole week, included a performance of L’Argia, an opera by a then very popular composer, Antonio Cesti. Christina’s journey to Rome, with a large entourage and accompanied by cardinals, felt like a triumphal procession. She arrived in Rome just before Christmas of 1655; the Pope Alexander VII received her as if she were a reigning Queen: a royal convert from Protestantism to Catholicism was a big catch for the Papacy. Festivities followed Christina’s arrival, and operas, still new as a genre and very popular in Rome, were at the center: Marco Marazzoli’s Vita humana, dedicated to Christina, an opera by Antonio Tenaglia, and Historia di Abraham et Isaac by Giacomo Carissimi. The staging venues were private palazzos: Palazzo Barberini and Palazzo Pamphilj – as there were no public opera theaters in Rome at the time, those were for Christina to establish.

Christina herself was initially installed inside the Vatican but a few weeks later moved into one of the most magnificent palazzos of Rome, Palazzo Farnese. Immediately she became the center of the intellectual life of Rome. She established Wednesdays as a day when the palazzo was opened to the nobility and artists to enjoy conversation and good music; a circle of friends that was formed early in 1656 eventually became the Accademia degli Arcadi, a literary academy which survives (as Accademia Letteraria Italiana) to this day. Over the following three and a half centuries, Popes, heads of state, musicians and poets were members. Christina stayed in Rome till September of that year, when she departed for France: France and Spain were contesting the control of Naples, and Christina, whose income was cut by the Swedes since her conversion, needed money. Her goal was to become the Queen of Naples, become financially independent and acquire a role in European politics. She stayed in France for almost two years, first greeted warmly by both Mazarin, the Chief Minister to King Lois XIV and the King himself but eventually wearing out her welcome. Without achieving anything politically, she returned to Rome in 1568 to a much cooler welcome.

She eventually settled in Palazzo Riario (now Corsini) in the Trastevere section of Rome, next to Palazzo Farnesina. She remained there for the rest of her life, save for short trips to Sweden again and Hamburg. She continued collecting art and her collection of Venetian masters was considered unsurpassed. She created a theater in her palace, and in 1667 helped to rebuild Teatro Tor di Nona, which became the first public opera theater in Rome. Her friends included the best painters (Gian Lorenzo Bernini among them) and poets of Rome, and above all, musicians. Major composers dedicated operas to her (Bernardo Pasquini, for example, and Alessandro Stradella), Giacomo Carissimi led her orchestra for a while, Arcangelo Corelli became one of her musicians (and also dedicated several of his compositions to her), and the 18 year-old Alessandro Scarlatti attracted her attention and became her Maestro di Capella. Christina wrote an autobiography (unfinished) and many essays on history and arts. She continued to be active in politics, proclaiming, for example, that Roman Jews were under her protection. In February of 1689 she fell ill and died on April 19th of 1689 at the age of 62. The Pope (Innocent XI, the fourth Pope during Christina’s time in Rome), ordered an official burial. Her body laid in state for four days and then was buried in the Saint Peter Basilica. Her books became part of the Vatican library; her collection of paintings became part of the famous Orleans Collection, which was eventually dispersed around Europe.

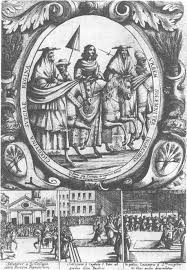

The engraving above (by Orazio Marinari) depicts her first, triumphal, entrance into Rome in 1655. She’s flanked by cardinals Orsini and Costaguti.Permalink