Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

May 30, 2016. Queen Christina – Part I. The 17th century was a time of great art and its glorious patrons, and Rome was the center of it all – art, music, riches, and patronage. We’ve written about one of the major figures of the time - Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni, but Queen Christina of Sweden, the benefactress of Giacomo Carissimi, Alessandro Stradella, Bernardo Pasquini, Arcangelo Corelli, Alessandro Scarlatti and so many others, was the one who set the example for all the powerful men that followed in her steps as major patrons of arts. Christina was an extraordinary person, unconventional in every possible way: socially, religiously, sexually, and artistically. She was born on December 18th of 1626 in Stockholm to Gustav II Adolf, King of Sweden. Her father, a great military leader who ably commanded the Swedish army during the Thirty Year War, made sure that she would inherit the throne in case of his death and that she was given extensive tutoring, ordinarily provided only to princes. In 1632 Gustav II was killed in battle and at the age of six Christina became Queen regnant. She eagerly continued her studies, learning Latin and Greek (eventually she learned eight more languages, including French and Italian, both of which she knew perfectly, German, Arabic and even Hebrew). She studied for10 hours a day and seemed to enjoy it. Philosophy and religion were her favorite subjects, and also history and mathematics. “She was not like a female,” was the judgment of one of her courtiers. Intellectually curious, the young Christina invited scholars and philosophers to the court; one of the visitors was a Portuguese rabbi and kabbalist, Menasseh ben Israel. With her guests, she discussed astronomy, theology and natural sciences. She even invited the celebrated French philosopher René Descartes, who came to Stockholm in 1649. They would meet every day, at 5 o’clock in the morning and talk for hours. The tasking schedule and drafty rooms affected Decartes’ health, four months later he caught a cold and died. Christina, who loved the theater (Pierre Corneille’s plays especially) was an amateur actress, and ordered to set one of the palace halls as a theater. In 1648 she invited the famous Flemish painter Jacob Jordaens to create 35 paintings for one of her castles. Around that time, she became one of the biggest collectors of art in Europe. Even though she was yet to get involved with music, these rather costly activities presaged her life as a major patron of arts later on, in Rome.

powerful men that followed in her steps as major patrons of arts. Christina was an extraordinary person, unconventional in every possible way: socially, religiously, sexually, and artistically. She was born on December 18th of 1626 in Stockholm to Gustav II Adolf, King of Sweden. Her father, a great military leader who ably commanded the Swedish army during the Thirty Year War, made sure that she would inherit the throne in case of his death and that she was given extensive tutoring, ordinarily provided only to princes. In 1632 Gustav II was killed in battle and at the age of six Christina became Queen regnant. She eagerly continued her studies, learning Latin and Greek (eventually she learned eight more languages, including French and Italian, both of which she knew perfectly, German, Arabic and even Hebrew). She studied for10 hours a day and seemed to enjoy it. Philosophy and religion were her favorite subjects, and also history and mathematics. “She was not like a female,” was the judgment of one of her courtiers. Intellectually curious, the young Christina invited scholars and philosophers to the court; one of the visitors was a Portuguese rabbi and kabbalist, Menasseh ben Israel. With her guests, she discussed astronomy, theology and natural sciences. She even invited the celebrated French philosopher René Descartes, who came to Stockholm in 1649. They would meet every day, at 5 o’clock in the morning and talk for hours. The tasking schedule and drafty rooms affected Decartes’ health, four months later he caught a cold and died. Christina, who loved the theater (Pierre Corneille’s plays especially) was an amateur actress, and ordered to set one of the palace halls as a theater. In 1648 she invited the famous Flemish painter Jacob Jordaens to create 35 paintings for one of her castles. Around that time, she became one of the biggest collectors of art in Europe. Even though she was yet to get involved with music, these rather costly activities presaged her life as a major patron of arts later on, in Rome.

At the age of nine Christina, after reading the biography of the English Queen Elisabeth, decided that she will not marry. She wrote about “distaste for marriage” in her unfinished autobiography. At the age of 23 she made an official announcement, and asked that her cousin Charles be appointed heir to the throne. For a Queen, she lived a very unusual life: studied all the time, slept just three - four hours a day, and often wore men’s clothes and shoes “for convenience (later in her life in Rome, though, she would wear dresses with such décolleté that even the Pope rebuked her). At the time, her closest friend was her lady-in-waiting, Ebba Sparre, with whom she was probably intimate. In 1651, totally exhausted, she suffered what probably was a nervous breakdown. Her French doctor banned all studies and ordered entertainment instead. Surprisingly, Christina took his advice to heart and abandoning her ascetic lifestyle.

While Sweden was Protestant, since an early age Christina had been interested in Catholicism. One of her confidants was Antonio Macedo, a Portuguese Jesuit. She developed plans to convert. Her unwillingness to marry and Catholicism were clearly conflicting with her position as Queen. In June of 1654 she abdicated in favor of her cousin, Charles Gustav. Few days later she left the country, first to Hamburg, then Antwerp and eventually Rome.Permalink

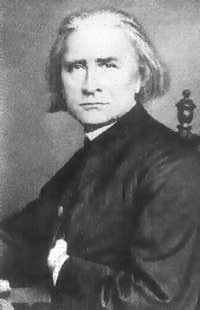

May 20, 2016. Franz Liszt, Venezia e Napoli. Today we’ll publish an article on Liszt’s Venezia e Napoli, a revision of the earlier set by the same name, which was published as a supplement to the Deuxième année: Italie. We’ll illustrate Gondoliera with a performance by the young Korean-American pianist Woobin Park, Canzone – by a 1985 recording made by the great Jorge Bolet, when he was 71, and Tarantella – with a performance by another young pianist, the American Heidi Hau. ♫

The cities of Venice and Naples must have made a particular impression upon Franz Liszt during his travels with Marie d’Agoult, for, beside the several pieces that would ultimately become the travelogue of his journeys through Italy in the second volume of Années de pèlerinage, he also composed in 1840 a further four pieces named after them—Venezia e Napoli. Like Années de perinage, Venezia e Napoli likewise underwent a significant process of revision once Liszt was in Weimar. Of the original four pieces, only the last two were kept: the Andante placido, which became Gondoliera; and the Tarantelles Napolitaines, which was simply renamed Tarantella. Liszt then inserted a doleful Canzone between these two pieces, creating the triptych now known today. It was published as a supplement to Deuxième Année in 1861.

during his travels with Marie d’Agoult, for, beside the several pieces that would ultimately become the travelogue of his journeys through Italy in the second volume of Années de pèlerinage, he also composed in 1840 a further four pieces named after them—Venezia e Napoli. Like Années de perinage, Venezia e Napoli likewise underwent a significant process of revision once Liszt was in Weimar. Of the original four pieces, only the last two were kept: the Andante placido, which became Gondoliera; and the Tarantelles Napolitaines, which was simply renamed Tarantella. Liszt then inserted a doleful Canzone between these two pieces, creating the triptych now known today. It was published as a supplement to Deuxième Année in 1861.

Liszt based Gondoliera (here), or “Gondolier’s song,” on a well-known melody (“La biondina in gondoletta”) composed by Giovanni Battista Peruchini, an Italian composer born in 1784. Unlike the original version, the 1859 revision opens with an extended introduction in the key of F-sharp minor. Undulating eighth notes in compound meter begin quietly in the bass and slowly rise towards the tonic. In the treble, glistening arpeggios instantly conjure the imagery of a peaceful Venetian canal. Eventually gaining an F-sharp major chord, the music pauses before the commencement of the melody. Marked sempre dolcissimo, the melody, in its first statement, sings out in the rich middle register of the piano above a tonic pedal suggested by the eighth notes still present in the bass. Two more statements follow, each separated by a brief fantasia in Liszt’s usual florid style. Only the latter half of the melody is present in the second statement, but is otherwise only slightly changed. The eighth notes of the bass, however, have now become sixteenths, imbuing the music with an increasing energy. The final statement, on the other hand, is greatly embellished. The melody, still essentially unaltered, now appears against a glimmering accompaniment of trills and broken chords, as if the gondola has suddenly emerged from between two buildings and brilliant sunlight now reflects off the surrounding waters. The melody is repeated again, now below the accompanimental arpeggios, and with its penultimate measure trailing off into a final passage of filigree. From there, the lengthy coda turns the melody somewhat wistful, as its strains are broken up and the minor key creeps back into the tonal fabric. On a stunningly beautiful passage in which full-voice chords move about a fixed F-sharp and A-sharp, the music fades away, like the empty gondola slowly receding from its former passenger. (Read more here).Permalink

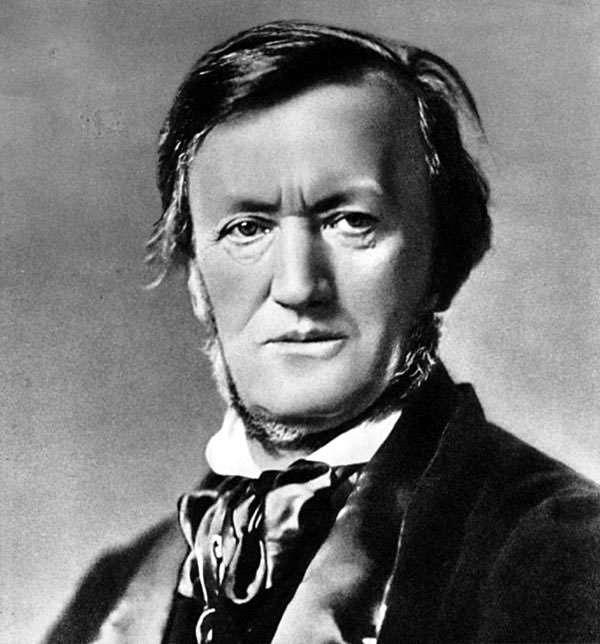

May 16, 2016. Wagner and more. Richard Wagner was born on May 22nd of 1813. Last year we wrote about his life around the time he created Tannhäuser. The premier of Lohengrin, the third of his so-called Romantic operas, followed five years later in 1850, although Wagner had started working on it several years earlier, in the mid-1840s. Wagner was still living and working in Dresden, where he was the Kapellmeister at the court of the King of Saxony. Before writing the libretto of Lohengrin, Wagner immersed himself in the old German epics, Parzival, by Wolfram von Eschenbach and Lohengrin; both written in the 13th century (the study of Parzival resulted, some 30 years later, in Wagner writing an idiosyncratic libretto for his last opera, Parsifal). The protagonist, Lohengrin, is the son of Parzival/Parsifal, one of King Arthur's Knights of the Round Table. Lohengrin is sent to rescue a certain maiden, and he undertakes the journey in a boat pulled by swans. The legend, used by Eschenbach to write his epics, originated around the time of the Crusades, so the great Minnesingers, born around 1160, worked with what may be considered “fresh material.” Wagner was still working on the opera when the 1848 insurrections in Paris and Vienna were followed by disturbances in all major cities of Europe. A year later, the left-leaning Wagner became politically active during the troubles in Dresden. As Prussian troops took over the city in May of 1849, Wagner fled to Weimar where he was sheltered for a while by Franz Liszt and then left for Zurich. He stayed out of Germany till 1860. It was Liszt, his future father-in-law, who directed the premier of Lohengrin in Weimar in August of 1850. The opera was a huge success, and not just in Germany – Riga, Vienna, Paris, St.-Petersburg premiers followed during the next several years. Unfortunately, 1850 was also the year when Wagner wrote his infamous article, Das Judenthum in der Musik (Jewishness in Music, often translated as Judaism in Music). Antisemitic and unfair (the article denigrates both Meyerbeer and Mendelssohn) it’s an utter embarrassment, especially considering the influence it had on the murderous anti-Semites of the following years. But going back to the music – Lohengrin, despite its usual Wagnerian length (at about 3 ½ hours, it’s actually among his shortest), is a wonderful opera. Here is the prelude to Act 1, performed by the Berlin Philharmonic, Herbert von Karajan conducting.

Romantic operas, followed five years later in 1850, although Wagner had started working on it several years earlier, in the mid-1840s. Wagner was still living and working in Dresden, where he was the Kapellmeister at the court of the King of Saxony. Before writing the libretto of Lohengrin, Wagner immersed himself in the old German epics, Parzival, by Wolfram von Eschenbach and Lohengrin; both written in the 13th century (the study of Parzival resulted, some 30 years later, in Wagner writing an idiosyncratic libretto for his last opera, Parsifal). The protagonist, Lohengrin, is the son of Parzival/Parsifal, one of King Arthur's Knights of the Round Table. Lohengrin is sent to rescue a certain maiden, and he undertakes the journey in a boat pulled by swans. The legend, used by Eschenbach to write his epics, originated around the time of the Crusades, so the great Minnesingers, born around 1160, worked with what may be considered “fresh material.” Wagner was still working on the opera when the 1848 insurrections in Paris and Vienna were followed by disturbances in all major cities of Europe. A year later, the left-leaning Wagner became politically active during the troubles in Dresden. As Prussian troops took over the city in May of 1849, Wagner fled to Weimar where he was sheltered for a while by Franz Liszt and then left for Zurich. He stayed out of Germany till 1860. It was Liszt, his future father-in-law, who directed the premier of Lohengrin in Weimar in August of 1850. The opera was a huge success, and not just in Germany – Riga, Vienna, Paris, St.-Petersburg premiers followed during the next several years. Unfortunately, 1850 was also the year when Wagner wrote his infamous article, Das Judenthum in der Musik (Jewishness in Music, often translated as Judaism in Music). Antisemitic and unfair (the article denigrates both Meyerbeer and Mendelssohn) it’s an utter embarrassment, especially considering the influence it had on the murderous anti-Semites of the following years. But going back to the music – Lohengrin, despite its usual Wagnerian length (at about 3 ½ hours, it’s actually among his shortest), is a wonderful opera. Here is the prelude to Act 1, performed by the Berlin Philharmonic, Herbert von Karajan conducting.

And now to a somewhat disappointing discovery. Maria Theresia von Paradis was born on May 15th of 1759. We always thought that she was famous for three things: being blind but creative in the age when that was so difficult; for Mozart writing a concerto for her, and the Sicilienne, a wonderful little piece, especially as played by Jacqueline du Pré (here). Unfortunately, the Groves Dictionary suggests that it was not Paradis who was the author of the piece but the purported “discoverer,” the violinist Samuel Dushkin, who arranged the music based on the violin sonata by Carl Maria von Weber and called it Sicilienne. And indeed, if you listen to the second movement of Weber’s Sonata op. 10 no. 1 (here, as played by Leonid Kogan and Grigory Ginsburg), there cannot be any doubt as to the source of the music. Dushkin, a wonderful violinist who worked extensively with Stravinsky and created a number of arrangement, is known to be an author of at least one other “musical hoax”: the so-called Grave for violin and orchestra by Johann Georg Benda, which had nothing to do with the 18th century Bohemian violinist and composer.Permalink

May 9, 2016. Monteverdi. Claudio Monteverdi, one of the most important composers in the history of European music, who bridged the Renaissance with the nascent Baroque and almost singlehandedly created a new musical form, the opera, was born on this day in 1567 in Cremona, Italy. We’ve written about Monteverdi in the past (here and here), so we’ll focus on just one, but critical, period in his life – his almost 20 year stay in Mantua at the court of Gonzagas. The Gonzagas, who ruled Mantua from the early 14th century till the beginning of the 18th, were one of the most illustrious and old houses of Italy. They lived in the famous Palazzo Ducale, which, with its 500 rooms, was one of the largest palaces in the country. The rule of Duke Vincenzo, from 1587 to 1612, was a high point. Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga was an extravagant patron of the arts and his court was brilliant. The Duke surrounded himself with poets (including Torquato Tasso), painters (Peter Paul Rubens was one of his favorites) and musicians – the court orchestra was one of the best, and led by the famous composer Giaches De Wert. The Duke spent so lavishly that by the end of his rule the Gonzagas ran out of money; historians believe that Vincenzo’s profligacy led to the decline of the Duchy. Monteverdi moved to Mantua around 1590 when he was 23. Though he had already established himself as a composer in his native Cremona, at the court he started at the bottom, as one of the court musicians. The influence of De Vert on his compositions of the period is unmistakable. Monteverdi’s talents didn’t go unnoticed for long as the Duke drew him into his inner circle. Monteverdi was one of the few musicians to accompany the Duke on his frequent trips. On one of such trip in 1600, they went to Florence to join the celebration of the wedding of Maria de’ Medici, daughter of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, to the French King Henri IV. Monteverdi, with the rest of Vincenzo’s retinue, attended the performance of Euridice, an opera by Jacopo Peri, one of the first operas ever written.

one, but critical, period in his life – his almost 20 year stay in Mantua at the court of Gonzagas. The Gonzagas, who ruled Mantua from the early 14th century till the beginning of the 18th, were one of the most illustrious and old houses of Italy. They lived in the famous Palazzo Ducale, which, with its 500 rooms, was one of the largest palaces in the country. The rule of Duke Vincenzo, from 1587 to 1612, was a high point. Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga was an extravagant patron of the arts and his court was brilliant. The Duke surrounded himself with poets (including Torquato Tasso), painters (Peter Paul Rubens was one of his favorites) and musicians – the court orchestra was one of the best, and led by the famous composer Giaches De Wert. The Duke spent so lavishly that by the end of his rule the Gonzagas ran out of money; historians believe that Vincenzo’s profligacy led to the decline of the Duchy. Monteverdi moved to Mantua around 1590 when he was 23. Though he had already established himself as a composer in his native Cremona, at the court he started at the bottom, as one of the court musicians. The influence of De Vert on his compositions of the period is unmistakable. Monteverdi’s talents didn’t go unnoticed for long as the Duke drew him into his inner circle. Monteverdi was one of the few musicians to accompany the Duke on his frequent trips. On one of such trip in 1600, they went to Florence to join the celebration of the wedding of Maria de’ Medici, daughter of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, to the French King Henri IV. Monteverdi, with the rest of Vincenzo’s retinue, attended the performance of Euridice, an opera by Jacopo Peri, one of the first operas ever written.

The Gonzagas were very close to the house of Este of the nearby Ferrara (the third wife of Alfonso II d’Este, the Duke of Ferrara at the time, was a Gonzaga). Alfonso shared Vincenzo’s love of arts and music; his court orchestra was led by Luzzasco Luzzaschi, a noted composer; he also maintained Concerto delle donne, a female vocal ensemble famous for their virtuosity. Monteverdi’s music was performed in Ferrara almost as often as in Mantua; in 1597 he was about to dedicate a book of madrigals to Duke Alfonso when the Duke died, childless, thus ending the Este’s dynasty in Ferrara.

While in Modena, Monteverdi wrote several books of madrigals (books Three through Five, the first two books were composed while Monteverdi lived in Cremona). Book Five is considered very significant, as it marks the shift from the polyphonic Renaissance style to a more monodic Baroque. In 1607 he composed his first opera, Orfeo, which firmly established opera as new art form; it’s also the earliest opera that is still being regularly performed. We’ll hear two madrigals from Book V: T'amo mia vita, performed by the ensemble Artek, under the direction of Gwendolyn Toth (here), and Che dar più vi poss'io, with Il Nuove Musiche conducted by Krijn Koetsveld (here).

PermalinkMay 2, 2016. Scarlatti, Brahms, Tchaikovsky. Three famous composers were born this week. May 2nd is the birthday of Alessandro Scarlatti, a very important early opera composer and the father of Domenico. Scarlatti was born in 1660. Then, on May 7th comes the unfortunate coupling of Johannes Brahms, born in 1833, and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, born in 1840, so very different but both representing the best in their national schools. Over the years we’ve written extensively about all three of them: here and here about Scarlatti, and of course numerous times about both Brahms and Tchaikovsky. So on this occasion we’ll celebrate their anniversaries with performances of just one piece each. We have to admit that we’re absolutely in love with the aria Mentre io godo in dolce oblio (here) from Oratorio La Santissima Vergine del Rosario and consider it on par with the best by Handel. It helps, of course, that it’s performed by the phenomenal Cecilia Bartoli (with Les Musiciens du Louvre conducted by Marc Minkowski). To carry the comparison between Scarlatti and Handel a bit further (hopefully not too far!), here’s a historical tidbit. Scarlatti’s La Santissima Vergine del Rosario was premiered in Rome in 1707. One of Scarlatti’s patrons during that time was Prince Francesco Maria Ruspoli, and Santissima was premiered on Easter Sunday at the Ruspoli palazzo. Around that time, the 22-year-old Handel arrived in Rome and almost immediately was hired by Prince Ruspoli as his Kapellmeister. One year later Handel composed his own oratorio, La Resurrezione. This one too was staged, lavishly, in the main hall on the ground floor of Ruspoli’s palazzo, and also on Easter Sunday. It’s safe to assume that Handel was familiar with Scarlatti’s work, although there are no discernable borrowings, except for the general format of the work.

Johannes Brahms, born in 1833, and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, born in 1840, so very different but both representing the best in their national schools. Over the years we’ve written extensively about all three of them: here and here about Scarlatti, and of course numerous times about both Brahms and Tchaikovsky. So on this occasion we’ll celebrate their anniversaries with performances of just one piece each. We have to admit that we’re absolutely in love with the aria Mentre io godo in dolce oblio (here) from Oratorio La Santissima Vergine del Rosario and consider it on par with the best by Handel. It helps, of course, that it’s performed by the phenomenal Cecilia Bartoli (with Les Musiciens du Louvre conducted by Marc Minkowski). To carry the comparison between Scarlatti and Handel a bit further (hopefully not too far!), here’s a historical tidbit. Scarlatti’s La Santissima Vergine del Rosario was premiered in Rome in 1707. One of Scarlatti’s patrons during that time was Prince Francesco Maria Ruspoli, and Santissima was premiered on Easter Sunday at the Ruspoli palazzo. Around that time, the 22-year-old Handel arrived in Rome and almost immediately was hired by Prince Ruspoli as his Kapellmeister. One year later Handel composed his own oratorio, La Resurrezione. This one too was staged, lavishly, in the main hall on the ground floor of Ruspoli’s palazzo, and also on Easter Sunday. It’s safe to assume that Handel was familiar with Scarlatti’s work, although there are no discernable borrowings, except for the general format of the work.

It is impossible to pick one representative piece by either Brahms or Tchaikovsky, so, with guided randomness, here are two compositions. A 1886 piano piece Dumka by Tchaikovsky, not to be confused with several “Dumka” compositions by Antonin Dvořák, isn’t played often on the concert scene, but it is very familiar to the Moscow audience: over the years, it has been performed repeatedly in the second round of the Tchaikovsky piano competitions. Here it is performed by a young Ukrainian pianist Stanislav Khristenko. The Piano sonata no. 3 written by the 20-year-old Brahms in 1853 isn’t too popular either: it’s long (35 minutes), in unusual five movements, and in parts uneven. The third piano sonata is also the last one for Brahms, who wrote all three in a span of less than two years. For all the problems, it’s very much worth listening to, especially when performed well, as it is here, by the young Japanese pianist Misato Yokoyama.Permalink

Ms. Thomas and Stephen Burns, a Chicago-based conductor, trumpeter, composer, and the Artistic Director of the Fulcrum Point New Music Project, are organizing a unique event, the Ear Taxi Festival 2016, a celebration of contemporary music in Chicago. The festival will feature 300 musicians, 53 world premieres and 4 installations in its six days of concerts, lectures, webcasts and artist receptions. Explaining the name of the festival, Ms. Thomas says: “We want to take your ears on a wide variety of ‘taxi rides’ through the world of contemporary music. At

Ms. Thomas and Stephen Burns, a Chicago-based conductor, trumpeter, composer, and the Artistic Director of the Fulcrum Point New Music Project, are organizing a unique event, the Ear Taxi Festival 2016, a celebration of contemporary music in Chicago. The festival will feature 300 musicians, 53 world premieres and 4 installations in its six days of concerts, lectures, webcasts and artist receptions. Explaining the name of the festival, Ms. Thomas says: “We want to take your ears on a wide variety of ‘taxi rides’ through the world of contemporary music. At  every concert, you’ll hear a mix of ensembles and musical styles that reflects the incredible depth and breadth of new music both here in Chicago and beyond.” The Festival will feature the music of more than 70 composers, from well-established, like Shulamit Ran, Ms. Thomas, Bernard Rands and George Flynn, to young but very promising. Here’s the list of all composers (with biographies). The performers are among the best in Chicago: ensembles, like the Avalon Quartet, the Chicago Composers Orchestra, Ensemble Dal Niente, the Fifth House ensemble and many more, as well as a number of individual performers. The Festival will start on October 5th and will run till October 10th of 2016. The concerts will take place at several venues: the Harris Theater, the Chicago Cultural Center, the Pritzker Pavilion of the Millennium Park, the University of Chicago and several other smaller ones. Here’s how you can buy tickets to the Festival events.

every concert, you’ll hear a mix of ensembles and musical styles that reflects the incredible depth and breadth of new music both here in Chicago and beyond.” The Festival will feature the music of more than 70 composers, from well-established, like Shulamit Ran, Ms. Thomas, Bernard Rands and George Flynn, to young but very promising. Here’s the list of all composers (with biographies). The performers are among the best in Chicago: ensembles, like the Avalon Quartet, the Chicago Composers Orchestra, Ensemble Dal Niente, the Fifth House ensemble and many more, as well as a number of individual performers. The Festival will start on October 5th and will run till October 10th of 2016. The concerts will take place at several venues: the Harris Theater, the Chicago Cultural Center, the Pritzker Pavilion of the Millennium Park, the University of Chicago and several other smaller ones. Here’s how you can buy tickets to the Festival events.

April 25, 2016. Augusta Read Thomas and Ear Taxi Festival. Augusta Read Thomas is one of the most interesting contemporary American composers. Prolific and active, she’s currently serving as the University Professor of Composition at the University of Chicago. To quote the music critic Edward Reichel, "Augusta Read Thomas has secured for herself a permanent place in the pantheon of American composers of the 20th and 21st centuries. She is without question one of the best and most important composers that this country has today. Her music has substance and depth and a sense of purpose. She has a lot to say and she knows how to say it — and say it in a way that is intelligent yet appealing and sophisticated.” Here are her Angel Musings, performed by the Orion Ensemble.

Please go to the Festival’s web page for more information. The Festival promises to be a wonderful affair and we hope that you’ll will have a chance to enjoy it.Permalink