Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

January 25, 2016. Mozart. January 27th marks the 260th anniversary of birth. Every year we focus on a different episode of Mozart’s life and present compositions from that period. Last year was about his rather unhappy trip to Paris in 1777- 1778. The 22 year-old Mozart had left Paris in September of 1778. He was offered a position in Salzburg at the court of the Prince Archbishop as an organist and concertmaster, and even though it paid three times his previous salary (450 florins instead of 150 – the New York Times has an interesting article on how much that would be in current dollars), Mozart was hesitant: he remembered the stifling atmosphere of Salzburg and was looking for an appointment in other places. He stayed in Mannheim and then in went to Munich but found no offers in either place. To make things worse, his Mannheim lover, the singer Aloysia Weber, seemed to have lost interest in him. (A quick note on these two cities. It was not by chance that Mozart was looking for employment there: Mannheim was famous for its orchestra, considered at that time the best in Germany. Munich had a strong musical connection: in 1778 the Elector Karl Theodor moved his court from Mannheim to Munich, bringing with him 33 musicians who became the core of his court’s orchestra; they also performed in the royal opera.) On January 15th of 1779 Mozart returned to Salzburg. For a while his relationship with Hieronymus Colloredo, the Prince-Archbishop, was quite good, but soon the same tensions that dominated their relationship before the Paris trip, became apparent again. Colloredo wanted Mozart to compose more church music while Mozart was getting more and more interested in opera and other non-liturgical genres. These difficulties were spelled out in a 1782 document appointing Michael Haydn, the younger brother of Franz Joseph Haydn, to the same position as Mozart had previously held: “we accordingly appoint [Michael Haydn] as our court and cathedral organist, in the same fashion as young Mozart was obligated, with the additional stipulation that he show more diligence … and compose more often for our cathedral and chamber music.” What Mozart did compose during that time were three symphonies (a short one, no. 32, no. 33 and no. 34, with a wonderfully energetic Finale, which you can hear in the performance by The Academy of Ancient Music, Christopher Hogwood conducting). Also, a concerto for two pianos, the famous Sinfonia Concertante for Violin and Viola and several other pieces, none of which could’ve been performed either in the Cathedral or at the Court. (Here’s the 1956 recording of the Concertante made by Jascha Heifetz, violin and Willian Primrose, viola)

1778. The 22 year-old Mozart had left Paris in September of 1778. He was offered a position in Salzburg at the court of the Prince Archbishop as an organist and concertmaster, and even though it paid three times his previous salary (450 florins instead of 150 – the New York Times has an interesting article on how much that would be in current dollars), Mozart was hesitant: he remembered the stifling atmosphere of Salzburg and was looking for an appointment in other places. He stayed in Mannheim and then in went to Munich but found no offers in either place. To make things worse, his Mannheim lover, the singer Aloysia Weber, seemed to have lost interest in him. (A quick note on these two cities. It was not by chance that Mozart was looking for employment there: Mannheim was famous for its orchestra, considered at that time the best in Germany. Munich had a strong musical connection: in 1778 the Elector Karl Theodor moved his court from Mannheim to Munich, bringing with him 33 musicians who became the core of his court’s orchestra; they also performed in the royal opera.) On January 15th of 1779 Mozart returned to Salzburg. For a while his relationship with Hieronymus Colloredo, the Prince-Archbishop, was quite good, but soon the same tensions that dominated their relationship before the Paris trip, became apparent again. Colloredo wanted Mozart to compose more church music while Mozart was getting more and more interested in opera and other non-liturgical genres. These difficulties were spelled out in a 1782 document appointing Michael Haydn, the younger brother of Franz Joseph Haydn, to the same position as Mozart had previously held: “we accordingly appoint [Michael Haydn] as our court and cathedral organist, in the same fashion as young Mozart was obligated, with the additional stipulation that he show more diligence … and compose more often for our cathedral and chamber music.” What Mozart did compose during that time were three symphonies (a short one, no. 32, no. 33 and no. 34, with a wonderfully energetic Finale, which you can hear in the performance by The Academy of Ancient Music, Christopher Hogwood conducting). Also, a concerto for two pianos, the famous Sinfonia Concertante for Violin and Viola and several other pieces, none of which could’ve been performed either in the Cathedral or at the Court. (Here’s the 1956 recording of the Concertante made by Jascha Heifetz, violin and Willian Primrose, viola)

In 1780 Mozart received a commission from Munich, from the Elector Karl Theodor himself, to compose a “serious” opera (opera seria). It was to become Mozart’s first mature opera, Idomeneo. (Here’s a Quartet Andrò ramingo e solo from Idomeneo with a great cast: Edita Gruberová and Lucia Popp, sopranos, Baltsa, mezzo-soprano and Luciano Pavarotti, tenor). The premier in Munich in January of 1781, with Mozart conducting, was highly successful. Papa Leopold traveled from Salzburg to attend. The whole family stayed in Munich for another two months. Then came a summons from Vienna where Archbishop Colloredo went to attend the celebrations of the accession of Joseph II as the Holy Roman Emperor. Spoiled by his triumph in Munich, Mozart was especially offended by the Archbishop treating him as a servant. In May of 1781 Mozart asked to be dismissed and a month later he was let go “with a kick on my arse,” as he wrote in a letter. Thus commenced the Viennese period of his life. The portrait of Mozart by Johann della Croce, above, is part of a picture of the family; it was made around the time of the described events, in 1780 or 1781.Permalink

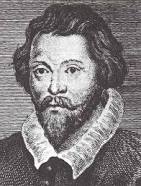

January 18, 2016. William Byrd. With numerous but minor stars who were born this week – two Russians, Cui (b. January 18th of 1835) and Tcherepnin (b. January 20th, 1899), three Frenchmen, Chabrier (1/18/1841, Chausson (1/20/1855) and Dutilleux (1/22/1916), and Muzio Clementi (b. January 23rd of 1753), an Italian who made his name in England – we’ll turn our attention to one of the greatest English composers of the Renaissance, William Byrd. We’ve mentioned him numerous times but have never written about him in detail. Byrd was born in London, probably in 1542 or 1543. If that’s the case, he would have been about 12 years younger than Orlando di Lasso and five years older than Tomás Luis de Victoria. Very little is known about Byrd’s early years. He was probably a chorister at the Chapel Royal and a pupil of the much older (and famous) Thomas Tallis. Some years later, in 1575, Queen Elisabeth granted Tallis and Byrd a “patent” to print and publish music, and historians surmise that the relationship between the two composers was that of a teacher and pupil. In 1563, Byrd was appointed the organist and master of choristers at the historic Lincoln Cathedral. Composing was one of his main responsibilities, and a number of compositions from that period have survived. Since the reign of Henry VIII, the Church of England had been separated from Rome, but Catholicism was still quite strong and tolerated. Byrd, who was probably raised Protestant, eventually converted to Catholicism, and it’s likely that the years at Lincoln were those of transition. Catholic music of the period was much more complex than the music of the Protestant churches, where a simple melody and clarity of diction were valued more than elaborate polyphony. At some point Byrd was even reprimanded by the Cathedral’s Dean for writing “papist” kind of music. But he also complied with the requirements of the Anglican service, as this wonderful example demonstrates: Magnificat, from his Short Service, is simple and clear (Truro Cathedral Choir is conducted by Andrew Nethsingha). Lincoln was also the place where Byrd composed his first pieces for the virginal (a small harpsichord), thus becoming one of the first composers of what would be known as the English “Virginalist” school (Orlando Gibbons, John Bull and Thomas Morley are among it’s more illustrious representatives).

Clementi (b. January 23rd of 1753), an Italian who made his name in England – we’ll turn our attention to one of the greatest English composers of the Renaissance, William Byrd. We’ve mentioned him numerous times but have never written about him in detail. Byrd was born in London, probably in 1542 or 1543. If that’s the case, he would have been about 12 years younger than Orlando di Lasso and five years older than Tomás Luis de Victoria. Very little is known about Byrd’s early years. He was probably a chorister at the Chapel Royal and a pupil of the much older (and famous) Thomas Tallis. Some years later, in 1575, Queen Elisabeth granted Tallis and Byrd a “patent” to print and publish music, and historians surmise that the relationship between the two composers was that of a teacher and pupil. In 1563, Byrd was appointed the organist and master of choristers at the historic Lincoln Cathedral. Composing was one of his main responsibilities, and a number of compositions from that period have survived. Since the reign of Henry VIII, the Church of England had been separated from Rome, but Catholicism was still quite strong and tolerated. Byrd, who was probably raised Protestant, eventually converted to Catholicism, and it’s likely that the years at Lincoln were those of transition. Catholic music of the period was much more complex than the music of the Protestant churches, where a simple melody and clarity of diction were valued more than elaborate polyphony. At some point Byrd was even reprimanded by the Cathedral’s Dean for writing “papist” kind of music. But he also complied with the requirements of the Anglican service, as this wonderful example demonstrates: Magnificat, from his Short Service, is simple and clear (Truro Cathedral Choir is conducted by Andrew Nethsingha). Lincoln was also the place where Byrd composed his first pieces for the virginal (a small harpsichord), thus becoming one of the first composers of what would be known as the English “Virginalist” school (Orlando Gibbons, John Bull and Thomas Morley are among it’s more illustrious representatives).

In 1572 Byrd was made a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal, a prestigious position through which he gained many powerful patrons among the courtiers of Queen Elisabeth, such as the Earl of Oxford and Lord Paget, the Earl of Worcester. The Queen herself was Byrd’s major benefactor. When she granted Byrd and Tallis a patent to publish music, their first issue, Cantiones, consisting of 34 multi-voice motets, was dedicated to the Queen. Here’s Byrd’s Motet for 6 voices, O lux beata Trinitas. It’s performed by the British Ensemble The Cardinall’s Musick, Andrew Carwood conducting. The years after 1575 were rather difficult for Byrd, as England became much less intolerant toward Catholics. Byrd was never directly prosecuted but at some point was suspended from the Chapel Royal. Byrd could no longer compose openly Catholic music; the most he could allow himself were motets, a form much more accepted in the Catholic service than the Anglican one. Byrd also continued to publish; his partner Tallis died in 1585, leaving Byrd the sole proprietor of the publishing company. Their earlier efforts weren’t commercially successful, but in the 1580s, Byrd, the monopolist, created a flourishing company. He also continued to compose, and here’s a Pavane from that period; Colin Tilney is at the harpsichord.

Byrd was to live another 40 productive years (he died on July 4th of 1623), and we’ll write about them later. Here is a short Agnus Dei from his Mass for Four Voices written in the later period of Byrd’s life. Simon Preston leads the Choir of Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford.Permalink

January 11, 2016. Pierre Boulez. This week we’d like to celebrate the life of Pierre Boulez, composer, conductor, educator, organizer, writer, and an all around remarkable person, who died on January 5th at the age of 90. Boulez was born on March 26th, 1925 in Montbrison, in central France. In his youth his interests were split between the piano and mathematics. Upon leaving Catholic school in 1941 he spent a year in Lyon studying higher math. In 1942 he moved to Paris. Pierre’s father wanted him to attend the Ecole Polytechnique, but instead he went to theParis Conservatory where he studied harmony with Olivier Messiaen. The Paris Conservatory was a very conservative place in those days. Even Messiaen, himself a modern composer of huge talent, didn’t teach Mahler and Bruckner. Later on, Boulez would mention in an interview that at that time in his mind “there were two twins: Mahler, Bruckner.” In the same interview he said that “German music stopped at Wagner,” so the Second Viennese School wasn’t taught at all. Boulez learned about atonal music from René Leibowitz, a student of Arnold Schoenberg. He had already felt the need to expand his music language and immediately adopted the new techniques. A year later, in 1945, the young Boulez wrote his first atonal piece of music, a set of twelve Notations for piano. He also wrote two piano sonatas, the second one, large in scale, published in 1950. His music was performed by the pianists Yvette Grimaud and Yvonne Loriod (at that time, Messiaen’s wife), but it was the circulation of the scores among musicians that brought Boulez fame among avant-garde musicians. In 1952 Loriod performed the sonata in Darmstadt to great acclaim. Thus started Boulez’s association with a group of tremendously talented and adventuresome composers and theoreticians that became known as the Darmstadt School. Darmstadt Summer Courses for New Music were held from the early 1950s to 1970. Every other year young musicians gathered in the city to present and discuss their music. Formal courses were taught both in composition and interpretation. Even the abridged list of the attendees looks very impressive: in addition to Boulez, there was Bruno Maderna, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Luigi Nono, Luciano Berio, György Ligeti, John Cage – composers who shaped the music of the second half of the 20th century. Philosophers and critics such as Theodor Adorno, presented their ideas. It was around that time that Boulez came up with his famous aphorism: “Any musician who has not felt … the necessity of the dodecaphonic language is OF NO USE.” In 1952 he wrote a seminal piece, “Le Marteau sans maître” (The hammer without a master) for voice and six instruments. Still difficult, even after half a century of music development, it could be heard here. Pierre Boulez conducts a small ensemble consisting of the flute, the guitar and several percussion instruments. Jeanne Deroubaix is the contralto. The period between 1950s and 1970s was the most productive for Boulez as a composer. In the following years he continued to write but dedicated much time to reworking some of the compositions of the earlier period.

France. In his youth his interests were split between the piano and mathematics. Upon leaving Catholic school in 1941 he spent a year in Lyon studying higher math. In 1942 he moved to Paris. Pierre’s father wanted him to attend the Ecole Polytechnique, but instead he went to theParis Conservatory where he studied harmony with Olivier Messiaen. The Paris Conservatory was a very conservative place in those days. Even Messiaen, himself a modern composer of huge talent, didn’t teach Mahler and Bruckner. Later on, Boulez would mention in an interview that at that time in his mind “there were two twins: Mahler, Bruckner.” In the same interview he said that “German music stopped at Wagner,” so the Second Viennese School wasn’t taught at all. Boulez learned about atonal music from René Leibowitz, a student of Arnold Schoenberg. He had already felt the need to expand his music language and immediately adopted the new techniques. A year later, in 1945, the young Boulez wrote his first atonal piece of music, a set of twelve Notations for piano. He also wrote two piano sonatas, the second one, large in scale, published in 1950. His music was performed by the pianists Yvette Grimaud and Yvonne Loriod (at that time, Messiaen’s wife), but it was the circulation of the scores among musicians that brought Boulez fame among avant-garde musicians. In 1952 Loriod performed the sonata in Darmstadt to great acclaim. Thus started Boulez’s association with a group of tremendously talented and adventuresome composers and theoreticians that became known as the Darmstadt School. Darmstadt Summer Courses for New Music were held from the early 1950s to 1970. Every other year young musicians gathered in the city to present and discuss their music. Formal courses were taught both in composition and interpretation. Even the abridged list of the attendees looks very impressive: in addition to Boulez, there was Bruno Maderna, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Luigi Nono, Luciano Berio, György Ligeti, John Cage – composers who shaped the music of the second half of the 20th century. Philosophers and critics such as Theodor Adorno, presented their ideas. It was around that time that Boulez came up with his famous aphorism: “Any musician who has not felt … the necessity of the dodecaphonic language is OF NO USE.” In 1952 he wrote a seminal piece, “Le Marteau sans maître” (The hammer without a master) for voice and six instruments. Still difficult, even after half a century of music development, it could be heard here. Pierre Boulez conducts a small ensemble consisting of the flute, the guitar and several percussion instruments. Jeanne Deroubaix is the contralto. The period between 1950s and 1970s was the most productive for Boulez as a composer. In the following years he continued to write but dedicated much time to reworking some of the compositions of the earlier period.

In 1970 President Georges Pompidou, bound to create a cultural legacy, asked Boulez, who was spending most of his time outside of France, to create an institute dedicated to research in music. The result was the IRCAM (Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique, or Institute for Research and Coordination Acoustic/Music). It was set in a building next to the Center Pompidou. With the addition two years later of the Ensemble InterContemporain, IRCAM became a major research and performing center for avant-garde music.

Boulez started conducting in 1957. First it was mostly his own music and that of his young colleagues, but eventually he expanded his repertoire to Stravinsky, Debussy, Webern and Messiaen. In the late 50’s he became the guest conductor of the Southwest German Radio Symphony Orchestra and took residence in Baden-Baden, to a large extent in protest to the conservativism of the French musical culture (that was before the IRCAM). A big break came in1971 when he was, rather unexpectedly, hired by the New York Philharmonic. During the following years he conducted every major orchestra, expanding his repertoire to include most of the classics (though he never conducted either Tchaikovsky or Shostakovich). Boulez became one of the greatest interpreters of Mahler. Here’s his tremendous interpretation of the 4th movement (Adagio. Sehr langsam und noch zurückhaltend) of Mahler’s Symphony no. 9 with the Chicago Symphony at its best. Permalink

January 6, 2016. Pierre Boulez, the great French composer and conductor, died last night in Baden-Baden, Germany. He was 90. Boulez burst on the European music scene in the aftermath of WWII as one of the leading composers of the Darmstadt School. In 1970 he founded IRCAM and in 1976, Ensemble InterContemporain. He started conducting in the 1960s and in 1971 was made the music director of the New York Philharmonic and the BBC Symphony Orchestra in London. Later he lead the Chicago Symphony and worked with the Concertgebouw and the Berlin Philharmonic. Even though his own musical sensibilities were very different, he became one of the greatest interpreters of the music of Mahler. Boulez wrote and talked about music more intelligently than most of the professional critics. We mourn the passing of this extraordinary figure.

January 4, 2016. Giuseppe Sammartini. Giuseppe Sammartini, not to be confused with his younger brother Giovanni Battista Sammartini, was born on January 6th of 1695 in Milan. Their father, Alexis Saint-Martin, a Frenchman, was an oboist, and he taught the instrument to his children. Both brothers became professional oboists playing in different professional orchestras, including that of the newly-opened Teatro Regio Ducal (this grand opera house burned down in 1776 and was replaced, in 1778, with the Nuovo Regio Ducal Teatro alla Scala, which we now know simply as Teatro alla Scala). Johann Joachim Quantz, a famous flutist and composer, considered Giuseppe the best oboe player in Italy. Sammartini probably also played the flute and the recorder: most oboists of the time played those instruments and Sammartini composed a large number of pieces for these instruments. One of his first compositions, an Oboe Concerto, was published in Amsterdam in 1717. In 1727 Sammartini moved to Brussels and then to London, where he was recognized as a supreme master of the oboe. He remained in England for the rest of his life. He became friendly with the composer Maurice Greene and played solos in the operas of Handel and Bononcini. In 1736 Sammartini accepted a lucrative position as a music teacher to the wife and the children of the Prince of Wales. He remained in this position till his death in 1750.

professional oboists playing in different professional orchestras, including that of the newly-opened Teatro Regio Ducal (this grand opera house burned down in 1776 and was replaced, in 1778, with the Nuovo Regio Ducal Teatro alla Scala, which we now know simply as Teatro alla Scala). Johann Joachim Quantz, a famous flutist and composer, considered Giuseppe the best oboe player in Italy. Sammartini probably also played the flute and the recorder: most oboists of the time played those instruments and Sammartini composed a large number of pieces for these instruments. One of his first compositions, an Oboe Concerto, was published in Amsterdam in 1717. In 1727 Sammartini moved to Brussels and then to London, where he was recognized as a supreme master of the oboe. He remained in England for the rest of his life. He became friendly with the composer Maurice Greene and played solos in the operas of Handel and Bononcini. In 1736 Sammartini accepted a lucrative position as a music teacher to the wife and the children of the Prince of Wales. He remained in this position till his death in 1750.

Sammartini, praised as “the greatest oboist that the world has ever known,” was said to have had a remarkable tone, which had the qualities of the human voice. He was also an influential teacher and helped to create the English oboe school. These days, though, he’s mostly remembered as a fine composer. During his lifetime he was known as a composer of chamber music, especially of flute sonatas and trios. Most of his concertos were published posthumously, but they are the ones that are most popular these days. Here’s his Concerto for the Recorder in F Major. It’s performed by Pamela Thorby, recorder, and the ensemble Sonnerie, Monica Huggett conducting. Sammartini wrote four keyboard concertos; here’s one of them, in A Major. Donatella Bianchi is on the harpsichord, ensemble I Musici Ambrosiani is conducted by Paolo Suppa, conductor. Finally, an Oboe Concerto, in this case, no. 12 in C Major, here. Franscesco Quaranta is playing oboe, also with I Musici Ambrosiani and Paolo Suppa.

Among many other birthdays this week are that of Francis Poulenc, who was born on January 7th of 1899 and Alexander Scriabin, born on January 6th of 1872. Here’s Scriabin’s Piano Sonata no. 10, his last piano sonata. It was composed in 1913, two years before the composer’s death. It’s performed by the American pianist Kathy Kim.Permalink

December 28, 2015. Still in the Christmas mood. So much great music has been written for Christmas that we decided to continue our celebration for a little longer. Last week, when we wrote about Giovanni Gabrieli, we mentioned one of his students, Heinrich Schütz. Schütz was 24 when he went to Venice. Half a century later, in 1660, at the advanced age of 75 he composed Weihnachtshistorie, The Christmas Story. By then he was an eminent composer, the “chief Kapellmeister” at the court of the Elector of Saxony. The Christmas Story is set to the text from the Gospels of Luke and Matthew as translated by Martin Luther. You can hear it in the performance by the Westfalische Kantorei under the direction of Wilhelm Ehmann.

Christmas Story. By then he was an eminent composer, the “chief Kapellmeister” at the court of the Elector of Saxony. The Christmas Story is set to the text from the Gospels of Luke and Matthew as translated by Martin Luther. You can hear it in the performance by the Westfalische Kantorei under the direction of Wilhelm Ehmann.

About 30 years later, around 1690, Arcangelo Corelli composed Twelve Concerti Grossi, his opus 6 (it wasn’t published till 1714). The set was commissioned by Corelli’s then new patron, Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni. Concerto number 8 had an inscription, Fatto per la notte di Natale (Made for the night of Christmas) and became known as the “Christmas Concerto.” It’s performed here, in a somewhat old-fashioned manner, by the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Herbert von Karajan conducting. Corelli had many pupils, one of them – Pietro Locatelli, composer and violinist. In 1721 Locatelli, then 26, also composed a set of 12 Concerti Grossi, and called the eighth “Christmas Concerto.” The last section of Corelli’s concert is marked as Largo. Pastorale ad libitum (that is, “at one’s pleasure”); the last section of Locatelli’s – Pastorale (Largo Andante). Not terribly original but lovely, it’s performed here by I Musici.

Let’s return to Germany. Here’s a wonderful hymn, Es ist ein' Ros' entsprungen, which Michael Praetorius included in his first published work, Musae Sioniae (The Muses of Zion) in 1609. The traditional translation of the hymn is “Lo, How a Rose E'er Blooming.” Even though Luther was strongly against the Catholic Marian cult, many of the older Catholic songs made it into the Lutheran liturgy, and Es ist ein' Ros' entsprungen is one of them: the text makes clear that the rosebud is “Mary, the pure.” The crystalline Monteverdi Choir is the performer. 125 years later, Johann Sebastian Bach wrote (and, to some extent, compiled) the great Christmas Oratorio. Consisting of six parts, the music was to be performed on Christmas and two following days, and also on New Year’s Day (the day of the circumcision of Jesus) and on the first Sunday of the new year. Here’s Sinfonia, the introductory part to the Second day service. John Elliot Gardiner conducts the English Baroque Soloists. The Adoration of the Magi, above, is by Domenico Ghirlandaio. It was painted around 1485.

Permalink