Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

This Week in Classical Music: June 10, 2024. On Place of Music in Culture, again. Edvard Grieg and Richard Strauss were born this week, the Norwegian on June 15th of 1843, and the German – on June 11th of 1864, but this is not what we want to write about this week. The pianist Bruce Liu played a recital in Chicago on Sunday a week ago. Mr. Liu is 27, he was born in Paris and raised in Montreal. Three years ago, he won the Chopin Piano Competition and since then his career has taken off. We heard good things about him, and his YouTube videos sounded interesting; we considered going to the concert but then circumstances intervened and we missed it. A couple of days later, interested in learning how Mr. Liu had played, we went online looking for a review. It turned out that not a single Chicago media outlet sent a reviewer to the concert: not the Chicago Tribune, not the Sun-Times, not even Larry Johnson’s Chicago Classical Review. We don’t know if Mr. Lui played well; what we do know is that the audience was very happy with him: he played six encores, all of them listed in the CSO updated program.

German – on June 11th of 1864, but this is not what we want to write about this week. The pianist Bruce Liu played a recital in Chicago on Sunday a week ago. Mr. Liu is 27, he was born in Paris and raised in Montreal. Three years ago, he won the Chopin Piano Competition and since then his career has taken off. We heard good things about him, and his YouTube videos sounded interesting; we considered going to the concert but then circumstances intervened and we missed it. A couple of days later, interested in learning how Mr. Liu had played, we went online looking for a review. It turned out that not a single Chicago media outlet sent a reviewer to the concert: not the Chicago Tribune, not the Sun-Times, not even Larry Johnson’s Chicago Classical Review. We don’t know if Mr. Lui played well; what we do know is that the audience was very happy with him: he played six encores, all of them listed in the CSO updated program.  Of course, the number of encores depends not only on the public’s enthusiasm but also on the performer – some prefer not to play any, as, for example, Sviatoslav Richter or Claudio Arrau later in their careers, others, likeEvgeny Kissin, enjoy playing them. Still, six encores at Orchestra Hall is a substantial number, which very likely reflects the audience’s appreciation, whether of the pianist's technique or musicianship, that we don’t know (that the technique is there is certain: listen to this half-minute Etude by Alkan).

Of course, the number of encores depends not only on the public’s enthusiasm but also on the performer – some prefer not to play any, as, for example, Sviatoslav Richter or Claudio Arrau later in their careers, others, likeEvgeny Kissin, enjoy playing them. Still, six encores at Orchestra Hall is a substantial number, which very likely reflects the audience’s appreciation, whether of the pianist's technique or musicianship, that we don’t know (that the technique is there is certain: listen to this half-minute Etude by Alkan).

And here’s another thing: while looking for a review, we came across one from the Stanford Daily. Musicians often perform on campuses, and it seems that student newspapers are better at covering classical music than the mainstream media (we saw several more of those). The review was enthusiastic if not very professional, but that was a minor problem. What caught our eye was a disclaimer that preceded the review itself. It said, “This article is a review and includes subjective thoughts, opinions and critiques.” Just think about it for a second: the readers, mostly students, were warned (or, in modern parlance, trigger-warned) that the article they’re about to read may include such scary things as “opinion and critique.” It is like the warning TV news programs give their thin-skinned viewer when covering wars, that some unpleasant things may be seen, probably because they don’t trust their audience to know what a war is. These warnings about thoughts, opinions and critiques are a direct consequence of the cultural metamorphosis on our campuses that also produced “safe spaces” and the notion of microaggression, and which, in the last years, spread out to society at large. It will take at least a generation to get rid of this inanity.

If anything, the program Bruce Liu played in Chicago was very imaginative: a sonata by Haydn, Chopin’s sonata no. 2, a piece by Kapustin, several pieces by Rameau, with Prokofiev’s Piano Sonata no 7 concluding the announced part of the program (the encores were by Bach, Chopin, Tchaikovsky and Liszt). Here’s one piece he played during the concert: Rameau’s Gavotte with six doubles from Nouvelles suites de pièces de clavecin. We think it’s very well-played, nuanced and in good taste. Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: June 2, 2024. Argerich and Bartoli. For several weeks now we’ve been posting entries about composers, neglecting the performers. In a way, it’s understandable: somehow, we value the creative talent of composers higher than that of performers and interpreters. It’s not immediately obvious why a gift from God of one type should be considered more important than another, especially considering that, historically, this has not always been the case, but this is a topic for another time. Two supremely gifted women were born this week, the pianist Martha Argerich, on June 5th of 1941, and the singer Cecilia Bartoli, on June 4th of 1966. Argerich, one of the most celebrated musicians of our time, still performs, at the age of 83. Here’s part of her schedule for June of this year: three performances on June 13th through 1

understandable: somehow, we value the creative talent of composers higher than that of performers and interpreters. It’s not immediately obvious why a gift from God of one type should be considered more important than another, especially considering that, historically, this has not always been the case, but this is a topic for another time. Two supremely gifted women were born this week, the pianist Martha Argerich, on June 5th of 1941, and the singer Cecilia Bartoli, on June 4th of 1966. Argerich, one of the most celebrated musicians of our time, still performs, at the age of 83. Here’s part of her schedule for June of this year: three performances on June 13th through 1 5th of Beethoven’s Second Piano Concerto in Rome at the Auditorium Il Parco Della Musica, then several concerts in Hamburg – playing Ravel’s La Valse for two pianos with Sergio Tiempo on the 20th, the next day playing chamber pieces of Schumann, Beethoven and Shostakovich, and the following day giving a concert of Chopin pieces. And it goes like that for the rest of the month, almost every day: Schumann’s Dichterliebe with Ema Nikolovska, Beethoven’s Triple Concerto with Gil Shaham and Edgar Moreau, some Debussy, Schubert and Mussorgsky, and on the last day of the month, Shostakovich’s Concerto no. 1, for piano and trumpet with Sergei Nakariakov, a Russian-Israeli, Paris-based trumpet virtuoso. What amazing energy! We wish her many years to come.

5th of Beethoven’s Second Piano Concerto in Rome at the Auditorium Il Parco Della Musica, then several concerts in Hamburg – playing Ravel’s La Valse for two pianos with Sergio Tiempo on the 20th, the next day playing chamber pieces of Schumann, Beethoven and Shostakovich, and the following day giving a concert of Chopin pieces. And it goes like that for the rest of the month, almost every day: Schumann’s Dichterliebe with Ema Nikolovska, Beethoven’s Triple Concerto with Gil Shaham and Edgar Moreau, some Debussy, Schubert and Mussorgsky, and on the last day of the month, Shostakovich’s Concerto no. 1, for piano and trumpet with Sergei Nakariakov, a Russian-Israeli, Paris-based trumpet virtuoso. What amazing energy! We wish her many years to come.

Cecilia Bartoli was born in Rome and studied there at the Santa Cecilia Conservatory. She made her opera debut at the age of 21, and one year later was already widely known in Europe. Bartoli has a rare voice, a coloratura mezzo-soprano, with a huge range and unique flexibility. This allowed her to sing not just the standard mezzo repertoire, such as Rosina in The Barber of Seville, Zerlina in Don Giovanni, Cherubino in The Marriage of Figaro, or Dorabella in Così fan tutte, all of which she did extremely well;, she also brought to life Baroque music rarely heard before, and almost never performed on such a level, not since the end of the era of castrati. Here, for example, is Bartoli performing two arias from Vivaldi’s opera Griselda. First, Agitata da due venti (Moved by the wind), recorded in 1998 with the ensemble Sonatori de la Gioiosa Marca, and next, Dopo Un'orrida Procella (After a horrible storm), recorded one year later with Il Giardino Armonico under the direction of Giovanni Antonini. We find Bartoli’s musicianship and technique incredible.

Here are the names of three conductors born this week, Yevgeny Mravinsky, born June 4th of 1903, who led the Leningrad Philharmonic for 50 years and was a great interpreter of the music of Tchaikovsky and Shostakovich; a wonderful Mahlerian, the German conductor Klaus Tennstedt (June 6th of 1926); and the Jewish Hungarian-American, George Szell (June 7th of 1897), who, among other things, made the Cleveland Orchestra into one of the best in the world. Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: May 27, 2024. Joachim Raff. The German composer Joachim Raff was born on this day in 1822. For all the years we’ve been writing these entries, not once did we mention his name. Of course, there are thousands of composers whose names escaped our attention, but these are usually second and third-tier; what makes Raff’s case unusual is that at the height of his popularity in the 1860s and 70s, his work was more popular than that of any other living German composer, including Bruckner (not at all popular during his lifetime) and Brahms. Soon after his death, Raff’s music was forgotten, and very few pieces are still performed today; it’s interesting to look back to see what attracted the sophisticated German public to his work and why it was abandoned so quickly. Raff, of German descent, was born in Switzerland, where his father escaped to avoid conscription during the Napoleonic wars. He was trained as a teacher, but as a musician, Raff was mostly self-taught (he became an accomplished pianist and organist); he started composing in his early 20s. Raff sent some of his work to Mendelssohn, who praised it and helped to get it published. In 1845 Raff, who lived in Zurich, met the great Franz Liszt. Liszt took a liking to him and found Raff a job in Cologne in a piano and music store. While in Cologne, Raff met Mendelssohn face-to-face and stayed in contact with Liszt. In 1847 he moved to Stuttgart and met the young Hans von Bülow. Bülow would later go to study with Liszt, marry his daughter Cosima, and then lose her to Wagner. He would also be one of the 19th-century best pianists and conductors. Bülow and Raff became best friends; Bülow had strong opinions and a sharp tongue and sometimes criticized Raff’s compositions but their friendship survived for the rest of Raff’s life.

we mention his name. Of course, there are thousands of composers whose names escaped our attention, but these are usually second and third-tier; what makes Raff’s case unusual is that at the height of his popularity in the 1860s and 70s, his work was more popular than that of any other living German composer, including Bruckner (not at all popular during his lifetime) and Brahms. Soon after his death, Raff’s music was forgotten, and very few pieces are still performed today; it’s interesting to look back to see what attracted the sophisticated German public to his work and why it was abandoned so quickly. Raff, of German descent, was born in Switzerland, where his father escaped to avoid conscription during the Napoleonic wars. He was trained as a teacher, but as a musician, Raff was mostly self-taught (he became an accomplished pianist and organist); he started composing in his early 20s. Raff sent some of his work to Mendelssohn, who praised it and helped to get it published. In 1845 Raff, who lived in Zurich, met the great Franz Liszt. Liszt took a liking to him and found Raff a job in Cologne in a piano and music store. While in Cologne, Raff met Mendelssohn face-to-face and stayed in contact with Liszt. In 1847 he moved to Stuttgart and met the young Hans von Bülow. Bülow would later go to study with Liszt, marry his daughter Cosima, and then lose her to Wagner. He would also be one of the 19th-century best pianists and conductors. Bülow and Raff became best friends; Bülow had strong opinions and a sharp tongue and sometimes criticized Raff’s compositions but their friendship survived for the rest of Raff’s life.

Raff followed Lisz to Weimar, where, as Liszt’s protégé, he entered the circle of “New German composers,” an influential group that included Wagner. There he met Brahms and the famous violinist and conductor Josef Joachim. He also met his future wife, actress Doris Genast. Things looked positive for a while but eventually, it became clear that opportunities in Weimer were limited. And so, even though Liszt aided Raff financially and supported his musical efforts, Raff decided to leave Weimar. Around 1858, he found a position in Wiesbaden and moved there. It was in Wiesbaden that Raff composed the majority of his work and achieved public recognition. His First Symphony, a 70-minute composition subtitled An das Vaterland (To the Fatherland) was composed between 1859 and 1861 and was well received. And so were many other works that followed: his Third Symphony (Im Walde, In the Forest) became one of the most often-performed symphonies of its time, and the Fifth (Lenore) was also received enthusiastically. His piano and violin concertos became popular and the chamber pieces were widely performed. It’s even said that Raff’s music had some influence on Tchaikovsky and Richard Strauss. It’s not clear why Raff was forgotten so quickly. Indeed, he was not very original, much of his music was too long, and he wrote too much of it. But the same could be said about some 19th-century composers who are still feted today. And some of Raff’s music is very pretty. These days very few of his pieces are played, his Fifth Symphony, Lenore, is one of them. You can judge for yourself whether it’s worth it. Here’s the 1st movement of this symphony. Yondani Butt is leading the Philharmonia Orchestra. And if you want to hear more, here’s the rest of the symphony: the 2nd, 3rd and 4th movements.

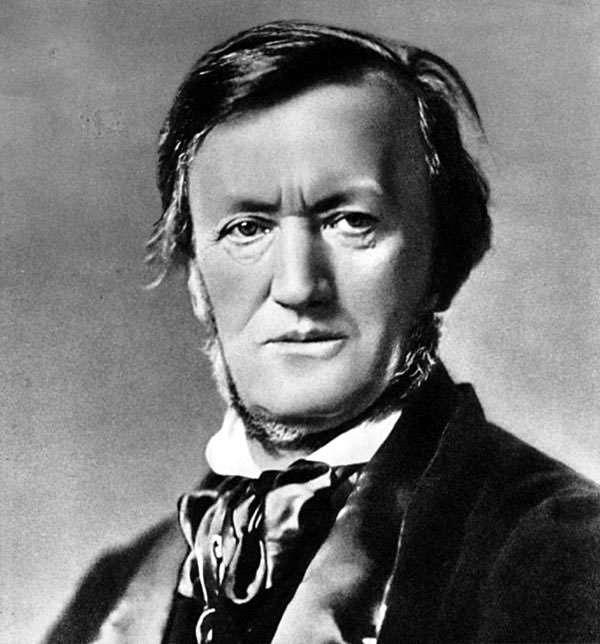

PermalinkThis Week in Classical Music: May 20, 2024. Wagner and Lighter Things. Richard Wagner’s 211th anniversary is on May 22nd: he was born in Leipzig in 1813. Wagner’s music is still so fresh (and often so controversial) that it feels strange that he was only two years younger than his stepfather, Franz Liszt, and three years younger than Frédéric Chopin and Robert Schumann, whose places in the pantheon of European music have been established a long time ago. Hitler’s love for his music didn’t help Wagner’s reputation, and neither did the composer’s abhorrent antisemitism. But if we put the non-musical considerations aside (and we recognize that it’s easier said than done), what we have is a musical genius, well ahead of his contemporaries, a composer whose music influenced generations of musicians all over the world, sometimes in very unexpected ways (think, for example, of the orchestral works of Claude Debussy, who had a love-hate relationship with Wagner).

still so fresh (and often so controversial) that it feels strange that he was only two years younger than his stepfather, Franz Liszt, and three years younger than Frédéric Chopin and Robert Schumann, whose places in the pantheon of European music have been established a long time ago. Hitler’s love for his music didn’t help Wagner’s reputation, and neither did the composer’s abhorrent antisemitism. But if we put the non-musical considerations aside (and we recognize that it’s easier said than done), what we have is a musical genius, well ahead of his contemporaries, a composer whose music influenced generations of musicians all over the world, sometimes in very unexpected ways (think, for example, of the orchestral works of Claude Debussy, who had a love-hate relationship with Wagner).

Liebestod, or Love Death in German, is the final music of Wagner’s opera Tristan und Isolde, and one of his best-known pieces. In it, Isolde sings over Tristan’s dead body. It’s a difficult piece, especially considering it comes at the end of an almost five-hour opera. In our library we have three recordings of this scene, with Kirsten Flagstad, Birgit Nilsson and Waltraud Meier; all three were leading Wagnerian sopranos of their generation. We like all three, but Flagstad’s probably the most, even though the recording quality is not great. Here it is, from 1936, with Fritz Reiner conducting the orchestra of the Royal Opera House (Covent Garden).

probably the most, even though the recording quality is not great. Here it is, from 1936, with Fritz Reiner conducting the orchestra of the Royal Opera House (Covent Garden).

On a much lighter note is the anniversary of Jean Françaix, whose music was sunny, witty and sophisticated. Françaix was born on May 23rd of 1912 in Le Mans. His musical gifts were obvious from an early age. He studied in Le Mans and then at the Paris Conservatory. He also took lessons with Nadia Boulanger, who considered him one of her most talented pupils, a praise of the highest order considering the many talented musicians who studied with her. Here’s Jean Françaix’s Concertino for Piano and Orchestra. The soloist is Claude Françaix, the composer’s daughter. The London Symphony Orchestra is conducted by Antal Dorati.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: May 13, 2023. Monteverdi and more. We’ll be brief this week, not that we’ve been too loquacious lately. Of the composers, the great Claudio Monteverdi, widely considered the most important composer of the end of the 16th – early 17th century, was born this week in 1567. He was baptized on May 15th in a church in Cremona, so most likely he was born a day earlier, on May 14th. In 2017, on Monteverdi’s 450th anniversary, we posted an entry about him. You can read it here.

widely considered the most important composer of the end of the 16th – early 17th century, was born this week in 1567. He was baptized on May 15th in a church in Cremona, so most likely he was born a day earlier, on May 14th. In 2017, on Monteverdi’s 450th anniversary, we posted an entry about him. You can read it here.

Maria Theresia Paradis, born May 15th of 1759 in Vienna, was a blind piano virtuoso. As a composer, she is remembered for one piece only, her Sicilienne, even though she authored several operas and cantatas. It was performed on the violin and cello, and served as the favorite encore piece to many, from Nathan Milstein to Jacqueline du Pré (here). The problem is that most likely, the Sicilienne wasn’t written by Paradis at all but is a hoax perpetrated by Samuel Dushkin, a Polish-American violinist. Dushkin claimed that he found it among Paradis’ piano pieces and arranged it for the violin, but such a manuscript was never found. Sill, Paradis helped to establish the first school for the blind (in 1785, in Paris) and should be remembered if not as a composer, then as a pioneering blind musician.

Also, Otto Klemperer, one of the most important German conductors, was born on May 24th of 1885 in Breslau, then the capital of German Silesia, now Wrocław, Poland. He was one of many Jewish musicians who escaped Germany after the Nazis took power in 1933. He left for Switzerland but ended up in the United States where he led several major orchestras, including the LA Philharmonic and the Pittsburgh Symphony. After WWII, Klemperer reestablished his career in Europe, especially in London. He died in Zurich in 1973.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: May 6, 2024. Brahms, Tchaikovsky, and more. Tomorrow is the birthday of two great composers, Johannes Brahms and Pyotr (Peter) Tchaikovsky. Brahms was born on May 7th of 1833 in Heide, a small town in northern Germany (then, the duchy of Schleswig-Holstein); Tchaikovsky – seven years later, in a small town of Votkinsk, not far from the Ural Mountains. Tchaikovsky is considered (at least, by the Russians) the greatest Russian composer, while Brahms is one of the “Three Bs” (with Bach and Beethoven). They lived through the same period (Brahms died in 1897, four years after Tchaikovsky), both were great symphonists, they wrote violin concertos that are considered among the best ever written, and their piano concertos are also hugely

was born on May 7th of 1833 in Heide, a small town in northern Germany (then, the duchy of Schleswig-Holstein); Tchaikovsky – seven years later, in a small town of Votkinsk, not far from the Ural Mountains. Tchaikovsky is considered (at least, by the Russians) the greatest Russian composer, while Brahms is one of the “Three Bs” (with Bach and Beethoven). They lived through the same period (Brahms died in 1897, four years after Tchaikovsky), both were great symphonists, they wrote violin concertos that are considered among the best ever written, and their piano concertos are also hugely popular. Nonetheless, their music is as different as it can be, and so were their lives: Brahms’s was steady, not very eventful (at least the way it manifested itself to outsiders), Tchaikovsky’s – full of tragedies, many of which related to his closeted homosexuality. Given the format of our entries, we can do justice neither to their biographies, nor their music: we've dedicated four entries to Arnold Schoenberg just to go into some detail, and here we have two very prolific composers. So instead, we’ll play their violin concertos, the ones we mentioned above, both featuring female soloists. Here’s Rachel Barton Pine playing Brahms (Chicago Symphony Orchestra is conducted by Carlos Kalmar); and here is the Tchaikovsky; Julia Fischer is the soloist, Yakov Kreizberg leads the Russian National Orchestra).

popular. Nonetheless, their music is as different as it can be, and so were their lives: Brahms’s was steady, not very eventful (at least the way it manifested itself to outsiders), Tchaikovsky’s – full of tragedies, many of which related to his closeted homosexuality. Given the format of our entries, we can do justice neither to their biographies, nor their music: we've dedicated four entries to Arnold Schoenberg just to go into some detail, and here we have two very prolific composers. So instead, we’ll play their violin concertos, the ones we mentioned above, both featuring female soloists. Here’s Rachel Barton Pine playing Brahms (Chicago Symphony Orchestra is conducted by Carlos Kalmar); and here is the Tchaikovsky; Julia Fischer is the soloist, Yakov Kreizberg leads the Russian National Orchestra).

Four composers were born on May 12th: Giovanni Battista Viotti, the famous Italian violinist and composer, in 1755; the Frenchman Jules Massenet, known for his operas Manon and Werther, in 1842; another, musically more adventuresome Frenchman, Gabriel Faure, three years later; and Anatoly Lyadov, the Russian composer known as much for his friendship with Tchaikovsky as for his small scale piano and orchestral pieces. Here’s Lyadov’s Kikimora (a nasty house spirit in Russian mythology); the Russian National Orchestra is conducted by Mikhail Pletnev.Permalink