Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

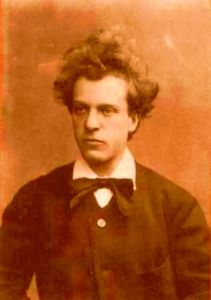

This Week in Classical Music: July 29, 2024. Rott and Ingegneri. Hans Rott was born this week, on August 1st of 1858. This composer, who died at 25 and was mad for the last several years of his tragically short life, continues to fascinate us. Clearly, he was a major talent, and who knows how he would’ve developed, but even within the limited scope of his output, one can discern musical ideas Mahler would develop some years later. We’ve written about him several times, here, for example. We are also happy to report that his Symphony in E major is being performed and recorded more often, the latest time being in 2021 for Deutsche Grammophon with the excellent Jakub Hrůša leading the Bamberger Symphoniker.

years of his tragically short life, continues to fascinate us. Clearly, he was a major talent, and who knows how he would’ve developed, but even within the limited scope of his output, one can discern musical ideas Mahler would develop some years later. We’ve written about him several times, here, for example. We are also happy to report that his Symphony in E major is being performed and recorded more often, the latest time being in 2021 for Deutsche Grammophon with the excellent Jakub Hrůša leading the Bamberger Symphoniker.

There are many very talented composers of the Renaissance that we have never written about, for the only reason that their birthdays are unknown, so they fall outside of the framework of the “classical music this week.” One of these composers is Marc'Antonio Ingegneri. He’s mostly forgotten these days, unjustly so in our opinion. If he is remembered at all, it is as the teacher of the great Claudio Monteverdi, but in his days, he was the leading composer of Cremona, one of the musical centers of Italy.

Ingegneri was born in Verona in 1535 or 1536, which made him about 10 years younger than Palestrina, three years younger than Orlando di Lasso, and about the same age as Giaches de Wert. As is usually the case with the composers of that era, we know little about his early days. He was a choirboy at the Verona cathedral and probably took lessons from Vincenzo Ruffo, a noted composer, also a Veronese, who was active as a music reformer, implementing an edict of the Council of Trent which stated that words in church music should be legible, a requirement that almost killed the polyphonic mass. Ingegneri left Verona in his early 20s and for a while played the violin in the band of the Scuola Grande di San Marco in Venice. It’s likely that in the 1560s he went to Parma to study with Cipriano de Rore, one of the noted composers of the mid-16th century. Sometime around 1566, Ingegneri moved to Cremona and soon after had his Primo libro de madrigali a quattro voci published. He was active in the music-making at the Cremona Cathedral, and in 1580 was made the maestro di cappella. Sometime soon after he became the teacher of the young Monteverdi, who was born in Cremona and was at the time 15 or 16 years old. It’s clear that Ingegneri was famous outside of Cremona, as he dedicated books of madrigals to his patrons in Milan, Parma, Verona, and even Vienna. His music was published in many cities, such as Venice, Milan, Brescia, Ferrara and Rome. For about a decade from the mid-1570s to the mid-1580s Ingegneri composed mostly secular madrigals, but then reverted to church music. He was a good friend of bishop Nicolò Sfondrato, later Pope Gregory XIV who ruled the Catholic church for just 11 months. Ingegneri died in Cremona on July 1st of 1592.

Here is Ingegneri’s motet for the feast of the Assumption of Mary, Vidi speciosam. The Choir of Girton College, Cambridge, and the Historic Brass of Guildhall School are led by Gareth Wilson.Permalink

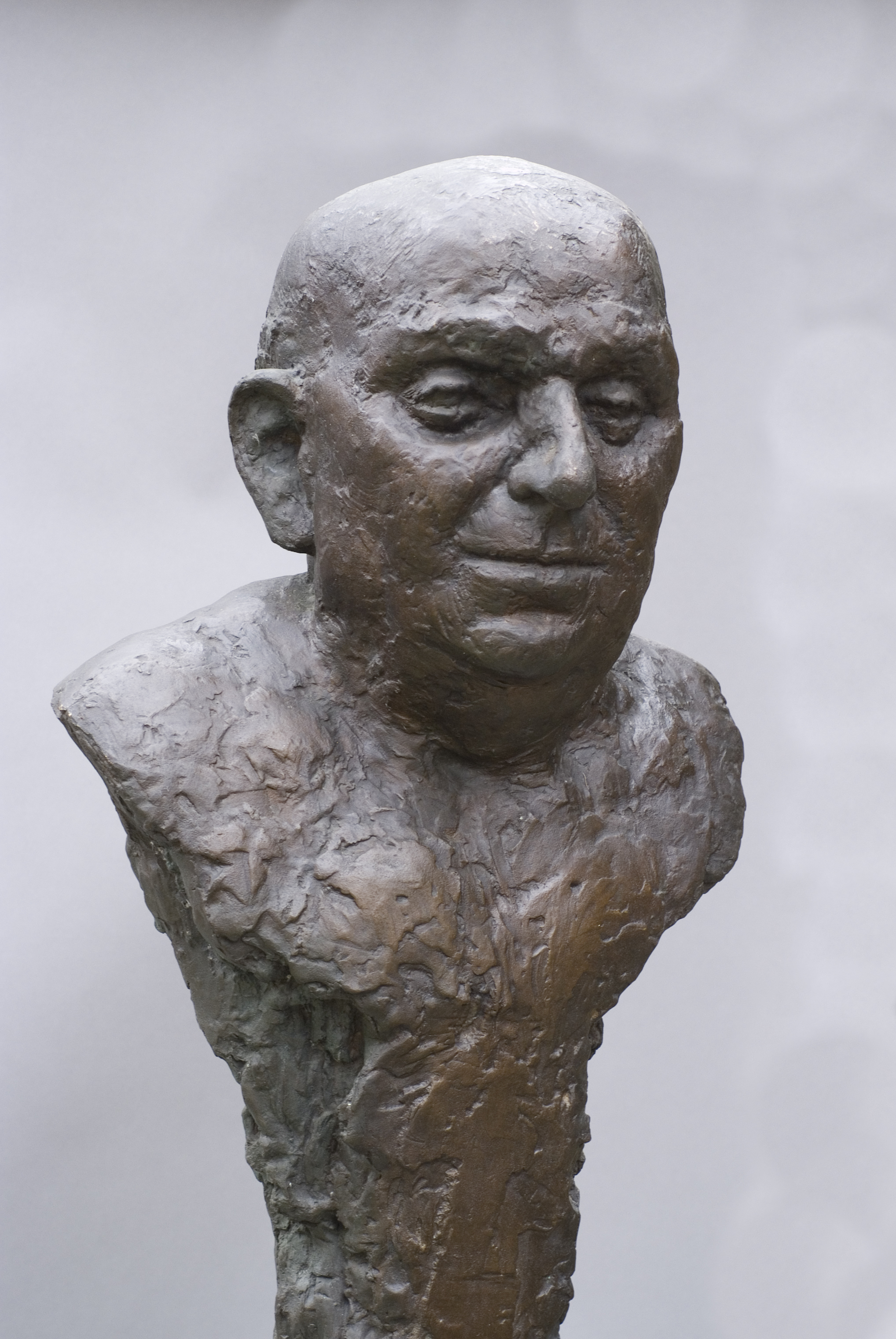

This Week in Classical Music: July 22, 2024. AlfredoCasella. About this time last year, we planned to celebrate Italian composer Alfredo Casella’s 100th anniversary but got involved with the lives of two German composers of the Nazi era and their very divergent paths: Carl Orff and Hanns Eisler. Eisler’s life is so fascinating that we returned to it this year with some added color provided by Hanns’s brother, a Comintern agent, and sister, one co-founder of the Austrian communist party and co-leader of the German one. But let’s get back to Alfredo Casella who was born on July 25th of 1883 in Turin. Not unlike Orff and Eisler, he lived through one of the most turbulent periods in modern history: the First World War, Mussolini’s fascist regime, and then the Second World War. Casella entered the Paris Conservatory in 1896 to study piano and composition, and while there he met "everybody": Debussy and Ravel, Stravinsky and Enescu, de Falla and Richard Strauss. He returned to Italy during the Great War and for some time taught at the Accademia di Santa Cecilia in Rome. He became involved in the new "futurist" music and even wrote a "futurist" piece, Pupazzetti (Puppets), here. But Casella’s interest in historical Futurism was fleeting. In 1917 he, together with composers Ottorino Respighi and Gian Francesco Malipiero founded the National Music Society to perform new Italian music and to "resurrect our old forgotten music." In 1923 Casella, the poet and playwright Gabriele D'Annunzio and the same Malipiero organized Corporazione delle nuove musiche (CDNM), again with the goals of promoting modern Italian music as well as reviving the old. CDNM brought to the then-provincial Italy a number of new composers, including Béla Bartók and Paul Hindemith; CDNM’s concerts also featured music of Schoenberg, Stravinsky, Poulenc, Kodály and other contemporaries.

the lives of two German composers of the Nazi era and their very divergent paths: Carl Orff and Hanns Eisler. Eisler’s life is so fascinating that we returned to it this year with some added color provided by Hanns’s brother, a Comintern agent, and sister, one co-founder of the Austrian communist party and co-leader of the German one. But let’s get back to Alfredo Casella who was born on July 25th of 1883 in Turin. Not unlike Orff and Eisler, he lived through one of the most turbulent periods in modern history: the First World War, Mussolini’s fascist regime, and then the Second World War. Casella entered the Paris Conservatory in 1896 to study piano and composition, and while there he met "everybody": Debussy and Ravel, Stravinsky and Enescu, de Falla and Richard Strauss. He returned to Italy during the Great War and for some time taught at the Accademia di Santa Cecilia in Rome. He became involved in the new "futurist" music and even wrote a "futurist" piece, Pupazzetti (Puppets), here. But Casella’s interest in historical Futurism was fleeting. In 1917 he, together with composers Ottorino Respighi and Gian Francesco Malipiero founded the National Music Society to perform new Italian music and to "resurrect our old forgotten music." In 1923 Casella, the poet and playwright Gabriele D'Annunzio and the same Malipiero organized Corporazione delle nuove musiche (CDNM), again with the goals of promoting modern Italian music as well as reviving the old. CDNM brought to the then-provincial Italy a number of new composers, including Béla Bartók and Paul Hindemith; CDNM’s concerts also featured music of Schoenberg, Stravinsky, Poulenc, Kodály and other contemporaries.

The 1920s was a time of great interest in European musical patrimony, the interest often tinged with nationalism. Like Respighi, who wrote The Birds and Ancient Airs and Dances, and Stravinsky (Pulcinella), Casella created pieces that echoed the music of his predecessors, in his case Scarlattiana (1926), an orchestral piece based on Domenico Scarlatti’s sonatas. And so, it was only natural that Casella became involved in the research and promotion of the music of Vivaldi. Ezra Pound and the violinist Olga Rudge, Pound’s companion, were also actively involved in reviving Vivaldi’s music. Pound at that time was a strong proponent of fascism; Casella too was a follower of Mussolini, especially his effort to create a national, state culture based on Italian cultural “self-sufficiency.” Casella of course was not the only one being seduced by fascism: most of the Italian cultural elites of the time, from D'Annunzio to painters Filippo Marinetti, Mario Sironi and even to some extent De Chirico, were either supporters of Mussolini or were strongly influenced by fascist ideals.

Casella’s wife was Jewish of French descent (they married in 1929), and when in 1938 Mussolini, under pressure from Hitler, passed racial laws, the life of the pro-regime Casella turned upside down. He lived in constant fear that his wife would be deported; at some point they split and Yvonne, Casella’s wife, went into hiding. On top of that, in 1942 he became seriously ill. Casella continued composing and teaching into the 1940s; his last composition was written in 1944, while Italy was a battlefield. It was called Missa Solemnis Pro Pace – a mass for peace. Among his many students was the composer Nino Rota, who wrote Cantico in memoria di Alfredo Casella. And a note for cinephiles: the Italian actress and filmmaker Asia Argento is Casella’s great-granddaughter.

Here's Casella’s Scarlattiana for piano and a small orchestra. Martin Roscoe is on the piano, Gianandrea Noseda conducts the BBC Philharmonic.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: July 8, 2024. Hanns Eisler, part II. We ended the first part of our Eisler story in 1933 when the Nazis took power in Germany. Eisler’s music was immediately banned, as were his friend Brecht’s plays, and both went into exile. Brecht settled in Denmark while Eisler moved from one place to another, temporarily living in Prague, Vienna, Paris, London, Moscow, Spain in 1937, during the Civil War, and other countries. He also visited the US, twice. In 1938 he permanently moved to the US, where he received a position at the New School for Social Research in New York. In 1942 Eisler moved to California, where Brecht had been living since 1941. They continued their cooperation: Brecht wrote the script for Fritz Lang’s movie, Hangmen Also Die!, and Eisler wrote the music, which was nominated for an Oscar. Eisler wrote music for seven other Hollywood films, receiving another Oscar nomination in 1945. He continued writing music for films for the rest of his creative life, 40 of them altogether – that was a major part of his creative output. In 1947 he published a book, Composing for the Films, co-written with another German exile, the philosopher Theodor Adorno.

banned, as were his friend Brecht’s plays, and both went into exile. Brecht settled in Denmark while Eisler moved from one place to another, temporarily living in Prague, Vienna, Paris, London, Moscow, Spain in 1937, during the Civil War, and other countries. He also visited the US, twice. In 1938 he permanently moved to the US, where he received a position at the New School for Social Research in New York. In 1942 Eisler moved to California, where Brecht had been living since 1941. They continued their cooperation: Brecht wrote the script for Fritz Lang’s movie, Hangmen Also Die!, and Eisler wrote the music, which was nominated for an Oscar. Eisler wrote music for seven other Hollywood films, receiving another Oscar nomination in 1945. He continued writing music for films for the rest of his creative life, 40 of them altogether – that was a major part of his creative output. In 1947 he published a book, Composing for the Films, co-written with another German exile, the philosopher Theodor Adorno.

That same year, 1947, he was brought before the Congress’s Committee on Un-American Activities. One of his accusers was his sister, Ruth Fischer, who by then had turned into a radical anti-Stalinist. She testified before the committee against her brothers, Hanns and Gerhart. She claimed that both of them were Soviet agents. Hanns, while a committed communist who lied on his US visa application, probably wasn’t an agent, whereas Gerhart was not only a Comintern agent but also a spymaster. Hanns was a well-known figure in the Hollywood German community and, as a noted composer active in leftist causes, in Europe as well. A worldwide campaign on his behalf was organized and led by many prominent intellectuals, among them Charlie Chaplin, Thomas Mann, Albert Einstein, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Igor Stravinsky, Aaron Copland and Jean Cocteau (Stravinsky is a surprising name on this list – he wasn’t known for his liberal views). Despite all that, Hanns Eisler was expelled from the US in March of 1948. He returned to Vienna, and, after a couple of trips to East Berlin, he settled in the German Democratic Republic for good. In 1949 he composed a song, Auferstanden aus Ruinen (Risen from the ruins) which became the country’s national anthem. Eisler was elected to the Academy of Arts and, for a while, feted as the most important composer of the Republic. Brecht moved to East Berlin in 1949 and established a theater company, the Berliner Ensemble. Together, Brecht and Eisler worked on 17 plays. While much of his previous output was dedicated to music of protest, in East Germany Eisler felt compelled to write music supporting the regime. No chamber music was written – that was too bourgeois. So the main output was “applied music“ for theater and movies, and songs, many for children and some for official occasions. Not everything was going well for Eisler: he wanted to compose an opera on the Faust theme, Johannes Faustus, and wrote a libretto for it, but the libretto was severely criticized in the press. Eisler got depressed and dropped the idea. Then, in 1956, Brecht died, and that depressed Eisler even more. He was encouraged by the 20th Congress of the Soviet Communist Party and its promise of de-Stalinization, but that didn’t have much effect on the repressive regime of East Germany. A lifelong communist, Eisler became disconnected from the realities of communist Germany. He suffered two heart attacks, the second killing him in September 1962. He was buried next to Brecht in Berlin.

Here, from the last pre-Nazi year, 1932, is Eisler’s Kleine Simphonie. Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin is conducted by Hans Zimmer.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: July 8, 2024. Mahler, Eisler. Last week, we wanted to write about Hanns Eisler who was born on July 7th but were sidelined by the 100th anniversary of the great cellist János Starker. July 7th was also the anniversary of Gustav Mahler, and we couldn’t miss it. Mahler was born in 1860; his last completed symphony, no. 9, was written between 1908 and 1909 (he died in 1911, at age 50). The last (fourth), movement of the symphony, Adagio, is one of the greatest pieces of music ever written, bar none. The movement preceding it, Rondo-Burleske, is denoted by Mahler as Allegro assai (Very cheerful) and Sehr trotzig (Very defiant). It’s complex, contrapuntal, and borderline insane, and not cheerful at all. It’s difficult for a conductor to interpret and for an orchestra to play. At the same time, if well done, it leads perfectly into the deathly serenity of the last movement. Here is Claudio Abbado with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra in a live 2010 performance. You can compare it with the interpretation by Pierre Boulez and Chicago, here.

great cellist János Starker. July 7th was also the anniversary of Gustav Mahler, and we couldn’t miss it. Mahler was born in 1860; his last completed symphony, no. 9, was written between 1908 and 1909 (he died in 1911, at age 50). The last (fourth), movement of the symphony, Adagio, is one of the greatest pieces of music ever written, bar none. The movement preceding it, Rondo-Burleske, is denoted by Mahler as Allegro assai (Very cheerful) and Sehr trotzig (Very defiant). It’s complex, contrapuntal, and borderline insane, and not cheerful at all. It’s difficult for a conductor to interpret and for an orchestra to play. At the same time, if well done, it leads perfectly into the deathly serenity of the last movement. Here is Claudio Abbado with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra in a live 2010 performance. You can compare it with the interpretation by Pierre Boulez and Chicago, here.

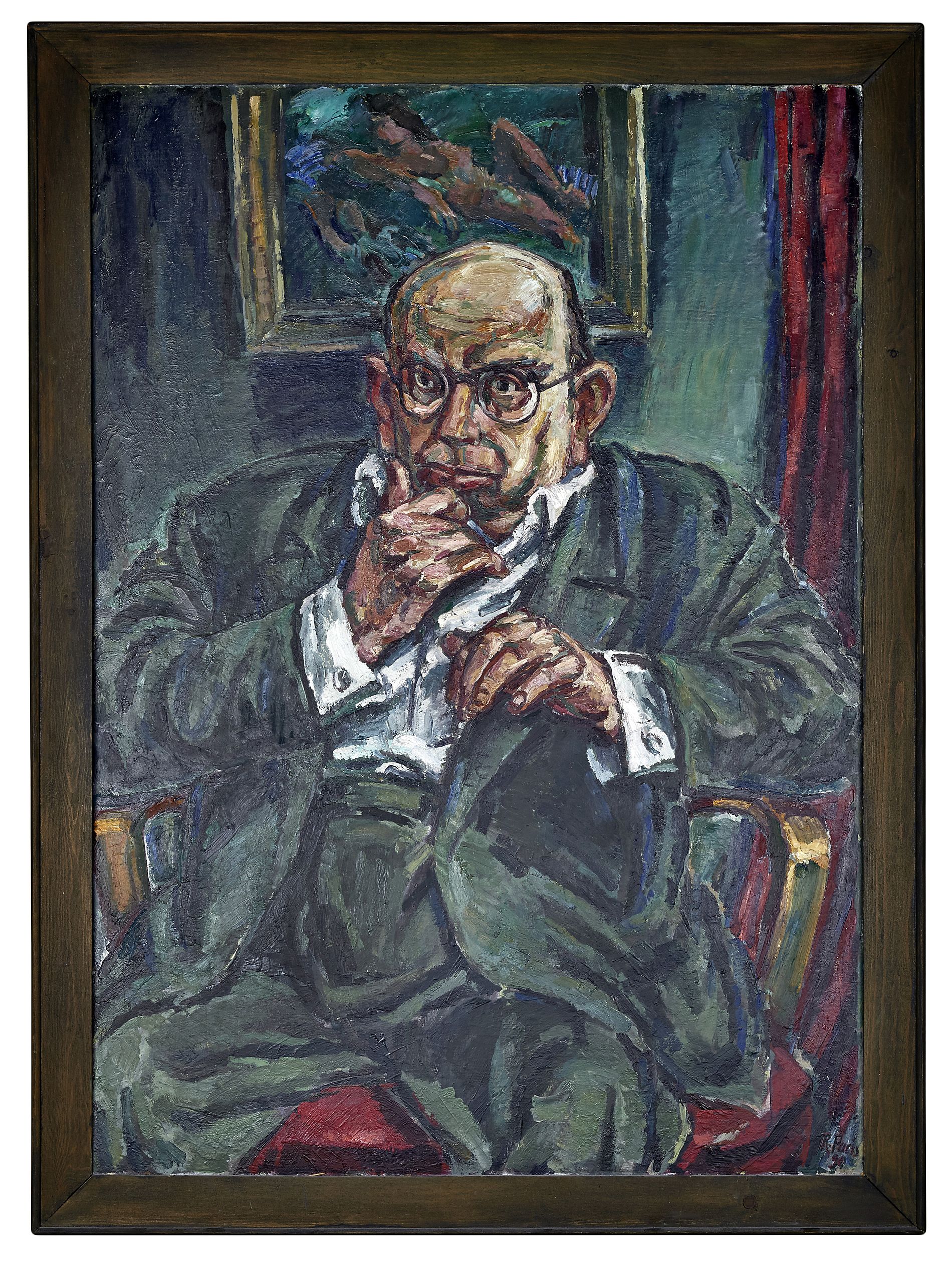

Now back to Hanns Eisler. Eisler was born in Leipzig, Germany, on July 7th of 1898; his father was Jewish, his mother Lutheran. The family was very political: Hanns’s brother was a prominent communist journalist, while his sister, Elfriede Eisler-Fischer, was a co-founder of the Austrian Communist party. In 1901 the family moved to Vienna. Hanns himself became active in politics at the age of 14, joining a Socialist youth group. During the Great War, Eisler served in the Austrian army. As a boy, he studied the piano on and off and composed some music (he did it even during the war). In 1918 the war was lost, the Austro-Hungarian empire disappeared; Eisler returned to the impoverished Vienna, now the capital of a tiny Austria, looking to continue his musical studies. He was accepted by Arnold Schoenberg, who taught him composition free of charge (Anton Webern sometimes was the substitute teacher). Inculcated in atonality and serialism, Eisler wrote several pieces that sounded very much like his teacher’s, especially the ones written for voice. Here, for example, is Palmström for Voice, Flute, Clarinet, Violin, Viola and Cello, which Schoenberg asked Eisler to write for a performance that also featured Pierrot lunaire (Junko Ohtsu- Bormann is the soprano). Eisler’s piano pieces of the period were light and fresh, as, for example, is the short Andante con moto, op. 3, no.1 (Siegfried Stöckigt is the pianist).

father was Jewish, his mother Lutheran. The family was very political: Hanns’s brother was a prominent communist journalist, while his sister, Elfriede Eisler-Fischer, was a co-founder of the Austrian Communist party. In 1901 the family moved to Vienna. Hanns himself became active in politics at the age of 14, joining a Socialist youth group. During the Great War, Eisler served in the Austrian army. As a boy, he studied the piano on and off and composed some music (he did it even during the war). In 1918 the war was lost, the Austro-Hungarian empire disappeared; Eisler returned to the impoverished Vienna, now the capital of a tiny Austria, looking to continue his musical studies. He was accepted by Arnold Schoenberg, who taught him composition free of charge (Anton Webern sometimes was the substitute teacher). Inculcated in atonality and serialism, Eisler wrote several pieces that sounded very much like his teacher’s, especially the ones written for voice. Here, for example, is Palmström for Voice, Flute, Clarinet, Violin, Viola and Cello, which Schoenberg asked Eisler to write for a performance that also featured Pierrot lunaire (Junko Ohtsu- Bormann is the soprano). Eisler’s piano pieces of the period were light and fresh, as, for example, is the short Andante con moto, op. 3, no.1 (Siegfried Stöckigt is the pianist).

Parallel to being involved with music, Eisler continued to be actively engaged in politics, and that, in turn, strongly affected his composition style. Eisler became a devoted Marxist and joined several radical leftist organizations, first in Austria and then, after moving to Germany in 1925, in Berlin where he applied for membership in the German Communist Party. He became disaffected with the “bourgeois” 12-tonal music and quarreled with Schoenberg who could not accept his student’s political views. Affected by ideology, Eisler switched to composing marches and solidarity songs, including Kominternlied, the unofficial hymn of the Comintern, the Soviet Union-led Communist International. Many of his songs became very popular with the European Left. They contained fighting words, and we should remember that that was the time when the Communists were literally fighting the Nazis on the streets of Germany.

In 1930 Eisler met the playwright Bertolt Brecht, one of the stars of the Left. They became lifelong friends and their cooperation led to several influential theatrical productions. We’ll finish the story of Hans Eisler during the Nazi period, his emigration and, later, his unexpected return to Germany, next week.Permalink

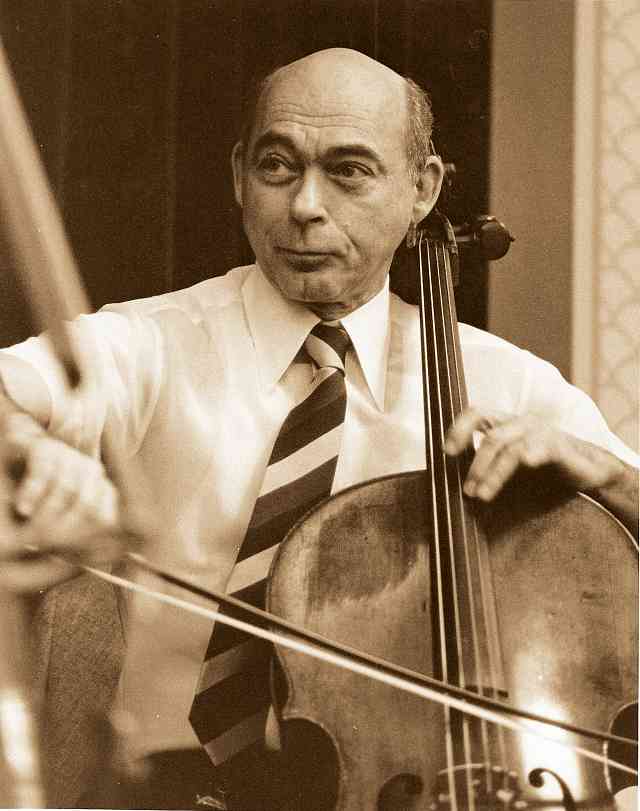

This Week in Classical Music: July 1, 2024. Sarker and more. We will celebrate János Starker’s 100th birthday on July 5th. One of the greatest cellists of the 20th century, Starker was born in Budapest in 1924 into a Jewish family. Starker, a child prodigy, entered the Budapest Academy at the age of seven and gave his first solo performance at 11. His teachers at the Academy were Leo Weiner, Zoltán Kodály, Béla Bartók and Ernő (Ernst von) Dohnányi – the pre-war Budapest Academy was a great music institution. Starker left the Academy in 1939, the year WWII started; he spent the wartime in Budapest and survived (the majority of the Budapest Jews were sent to Auschwitz in the last months of the war and perished there; two of his older brothers were murdered by the Nazis). After the war, with Budapest occupied by the Soviets, Starker joined the Budapest Philharmonic Orchestra as Principal Cello. In 1946 he left Hungary, going to Paris first and two years later to the US. He became the principal cellist of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra whose music director was a fellow Hungarian Jewish conductor Antal Doráti. From 1949 to 1953 Starker was the principal cello of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, then under the direction of Fritz Reiner, another Jewish musician from Budapest. From 1953 to 1958 he occupied the same position at the Chicago Symphony, which at that time was also led by Reiner. In 1958 Starker was appointed professor of cello at Indiana University, Bloomington; he remained there for the rest of his life. He toured widely and made many recordings.

born in Budapest in 1924 into a Jewish family. Starker, a child prodigy, entered the Budapest Academy at the age of seven and gave his first solo performance at 11. His teachers at the Academy were Leo Weiner, Zoltán Kodály, Béla Bartók and Ernő (Ernst von) Dohnányi – the pre-war Budapest Academy was a great music institution. Starker left the Academy in 1939, the year WWII started; he spent the wartime in Budapest and survived (the majority of the Budapest Jews were sent to Auschwitz in the last months of the war and perished there; two of his older brothers were murdered by the Nazis). After the war, with Budapest occupied by the Soviets, Starker joined the Budapest Philharmonic Orchestra as Principal Cello. In 1946 he left Hungary, going to Paris first and two years later to the US. He became the principal cellist of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra whose music director was a fellow Hungarian Jewish conductor Antal Doráti. From 1949 to 1953 Starker was the principal cello of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, then under the direction of Fritz Reiner, another Jewish musician from Budapest. From 1953 to 1958 he occupied the same position at the Chicago Symphony, which at that time was also led by Reiner. In 1958 Starker was appointed professor of cello at Indiana University, Bloomington; he remained there for the rest of his life. He toured widely and made many recordings.

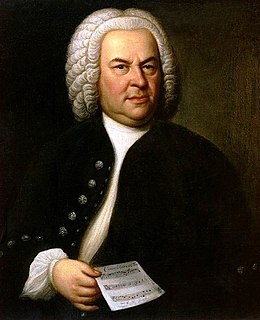

Starker recorded the complete set of Bach’s cello suites five times, the first recording made in 1950-52, the last – in 1997; that one won a Grammy. Here’s Johann Sebastian Bach’s Suite no. 5 in c minor. János Starker recorded it in New York on April 15th and 15th of 1963. There are many wonderful performances of this piece, we think this is one of the very best.

Starker died in Bloomington, Indiana, on April 28th of 2013.

We’d also like to mention several other names. Hans Werner Henze, an influential and prolific German composer, was born in Dresden on July 1st of 1926. And more than two centuries earlier, on July 2nd of 1714, another German, the great Christoph Willibald Gluck was born in the village of Erasbach, now part of Berching, a town in Bavaria.

We wanted to write about Hanns Eisler but Starker’s 100th anniversary intervened. Eisler, a composer of considerable talent, strong political opinions and an unusual life, was born on July 6th of 1898. We’ll write about him next week.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: June 17, 2024. Benedetto Marcello. Benedetto Marcello, born on June 24th of 1686, was an unusual composer: a Venetian patrician, he was an amateur musician. His father wanted Benedetto to become a lawyer, which he did, and was so successful in this profession that at the age of 20, he was admitted to the Great Council of Venice, and five years later elected to the Council of Forty, Venice’s Supreme Court. In 1730 he was sent to Pula in Istria, then part of the Venetian Republic and now in Croatia, to serve as Governor (it could’ve been an exile, but we don’t know). He stayed in Pula for eight years and then retired to Brescia as a papal chamberlain. He died there of tuberculosis in 1739. While a successful public servant (and also a poet), Marcello’s real love was music. He took some lessons in his youth but never had formal musical training. He probably started composing around 1710: as he was never associated with any musical institution, researchers have a difficult time dating his work. He wrote some instrumental pieces, but Marcello’s main interest was sacred music. A collection titled Estro poetico-armonico (it could be roughly translated as Poetic and Harmonic Inspiration) consists of 50 psalms (Salmi), several masses, and a Requiem. Here are Kyrie I and II, from the Requiem. Academia de li Musici is led by Filippo Maria Bressan. And here is one of his Salmi, Psalm 3, O Dio perché. Konrad Junghänel conducts the ensemble Cantus Cölln.

musician. His father wanted Benedetto to become a lawyer, which he did, and was so successful in this profession that at the age of 20, he was admitted to the Great Council of Venice, and five years later elected to the Council of Forty, Venice’s Supreme Court. In 1730 he was sent to Pula in Istria, then part of the Venetian Republic and now in Croatia, to serve as Governor (it could’ve been an exile, but we don’t know). He stayed in Pula for eight years and then retired to Brescia as a papal chamberlain. He died there of tuberculosis in 1739. While a successful public servant (and also a poet), Marcello’s real love was music. He took some lessons in his youth but never had formal musical training. He probably started composing around 1710: as he was never associated with any musical institution, researchers have a difficult time dating his work. He wrote some instrumental pieces, but Marcello’s main interest was sacred music. A collection titled Estro poetico-armonico (it could be roughly translated as Poetic and Harmonic Inspiration) consists of 50 psalms (Salmi), several masses, and a Requiem. Here are Kyrie I and II, from the Requiem. Academia de li Musici is led by Filippo Maria Bressan. And here is one of his Salmi, Psalm 3, O Dio perché. Konrad Junghänel conducts the ensemble Cantus Cölln.

An interesting tidbit: Faustina Bordoni, one of the most famous singers of the 18th century, Handel’s favorite, and the wife of the composer Johann Adolf Hasse, was “brought up under the protection of the brothers Alessandro and Benedetto Marcello,” as per Grove Music, and later received lessons from the brothers.

Handel’s favorite, and the wife of the composer Johann Adolf Hasse, was “brought up under the protection of the brothers Alessandro and Benedetto Marcello,” as per Grove Music, and later received lessons from the brothers.

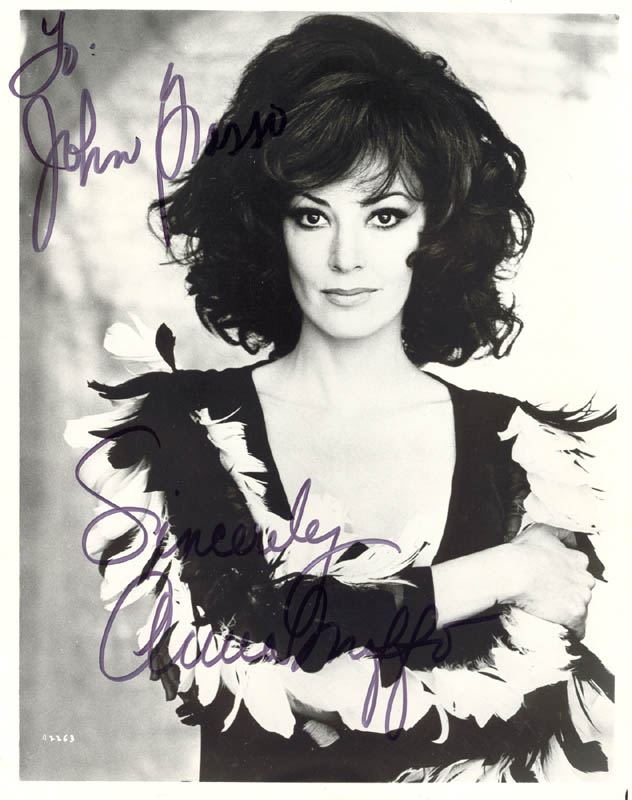

And speaking of singers, Anna Moffo was born on June 27th of 1932 in Philadelphia into a family of poor Italian immigrants. She studied at the Curtis and then in Italy. There, in 1955, she made her debut in Don Pasquale. Then, still just 23 and virtually unknown (but very pretty), she was offered the role of Cio-Cio San by RAI, the main Italian TV company. Madama Butterfly was telecast in January of 1956 and made Moffo famous overnight. Her career took off: she was asked to join Maria Callas, Giuseppe di Stefano and Rolando Panerai in the 1956 now-famous recording of La bohème, conducted by Karajan. In 1957 she premiered at the La Scala, and the Vienna State Opera, and in 1959 made her debut at the Metropolitan. Moffo had a beautiful lyric soprano voice; she also sang coloratura roles. Here she is, singing Sì. Mi chiamano Mimi, from Act I of La bohème. Tullio Serafin conducts the Rome Opera House Orchestra.

And so that we don’t forget, Claudio Abbado, one of our all-time favorite conductors, was born on June 26th of 1933. Permalink