Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

This Week in Classical Music: September 2, 2024. Bruckner 200. Several composers were born this week, the first and foremost of them – Anton Bruckner. We’re celebrating his 200th anniversary: Bruckner was born September 4th of 1824 in Ansfelden, a village outside of Linz. We love Bruckner and have written about him on many occasions, him personally (here, for example), as well as his music (here, about one of the several symphonies that we’ve touched upon). We had mentioned Bruckner’s notorious lack of confidence often: he was convinced that professional musicians knew and understood his music better than he did himself. This resulted in Bruckner rewriting major parts of practically all his symphonies over and over, sometimes following innocuous comments. In best cases we’re left with many editions of the same symphony: for example, he revised his Symphony no. 4, one of his most popular symphonies today, five times, and there are numerous editions of each revision, around 10 of them altogether. The Fourth was composed in 1872, the first revision followed one year later while the last one – in 1892, twenty years after the original composition was put to paper. But sometimes, things turned out much worse. Between January and September of 1869, Bruckner composed a symphony. It followed Symphony no. 1, which Bruckner completed in 1866 (as usual, many versions would follow, all the way to 1891), so he called it Symphony no. 2 (in D minor). Then, Otto Dessoff, a minor composer but a noted conductor who then led the Vienna Philharmonic, made a comment, and we’ll quote Georg Tintner, an Austrian conductor, on the consequences. "How an off-hand remark, when directed at a person lacking any self-confidence, can have such catastrophic consequences! Bruckner, who all his life thought that able musicians (especially those in authority) knew better than he did, was devastated when Otto Dessoff (then the conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic) asked him about the first movement: "But where is the main theme?" In the aftermath, Bruckner failed to submit the Symphony for a performance, and some years later, while reviewing his output, wrote "annullirt" ("nullified") on the front page and replaced the number (no. 2) with a symbol "∅" which was later interpreted as zero (0). Since then, the symphony acquired the designation of “Symphony no. 0.” The first performance was made in 1924, 55 years after it was completed, and the first recording – some nine years later, in 1933. There are many wonderful recordings of the symphony, one of them made by Bernard Haitink in 1966 with the Concertgebouw Orchestra. You can listen to it here.

anniversary: Bruckner was born September 4th of 1824 in Ansfelden, a village outside of Linz. We love Bruckner and have written about him on many occasions, him personally (here, for example), as well as his music (here, about one of the several symphonies that we’ve touched upon). We had mentioned Bruckner’s notorious lack of confidence often: he was convinced that professional musicians knew and understood his music better than he did himself. This resulted in Bruckner rewriting major parts of practically all his symphonies over and over, sometimes following innocuous comments. In best cases we’re left with many editions of the same symphony: for example, he revised his Symphony no. 4, one of his most popular symphonies today, five times, and there are numerous editions of each revision, around 10 of them altogether. The Fourth was composed in 1872, the first revision followed one year later while the last one – in 1892, twenty years after the original composition was put to paper. But sometimes, things turned out much worse. Between January and September of 1869, Bruckner composed a symphony. It followed Symphony no. 1, which Bruckner completed in 1866 (as usual, many versions would follow, all the way to 1891), so he called it Symphony no. 2 (in D minor). Then, Otto Dessoff, a minor composer but a noted conductor who then led the Vienna Philharmonic, made a comment, and we’ll quote Georg Tintner, an Austrian conductor, on the consequences. "How an off-hand remark, when directed at a person lacking any self-confidence, can have such catastrophic consequences! Bruckner, who all his life thought that able musicians (especially those in authority) knew better than he did, was devastated when Otto Dessoff (then the conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic) asked him about the first movement: "But where is the main theme?" In the aftermath, Bruckner failed to submit the Symphony for a performance, and some years later, while reviewing his output, wrote "annullirt" ("nullified") on the front page and replaced the number (no. 2) with a symbol "∅" which was later interpreted as zero (0). Since then, the symphony acquired the designation of “Symphony no. 0.” The first performance was made in 1924, 55 years after it was completed, and the first recording – some nine years later, in 1933. There are many wonderful recordings of the symphony, one of them made by Bernard Haitink in 1966 with the Concertgebouw Orchestra. You can listen to it here.

Bruckner had many detractors, Johannes Brahms being the foremost. Antonin Dvořák, Brahms’s follower and beneficiary, was also one of them. Dvořák was born on September 8th of 1841 in Nelahozeves, a village near Prague, then part of the Austrian Empire. His Symphony No.9, "From the New World," ranks highly on many lists of “most popular symphonies.” Clearly, Dvořák was a talented composer, but compared to Bruckner’s they sound somewhat trite, whereas Bruckner’s are fresh and, even now, innovative.

This was a rather special week: Darius Milhaud, Johann Christian Bach, Giacomo Meyerbeer, John Cage, Amy Beach, Isabella Leonarda, and Hernando De Cabezon were all born within these seven days. We’ll come back to some of them at a later date.Permalink

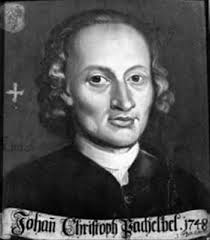

This Week in Classical Music: August 26, 2024. Performers and Conductors. Few composers were born this week; we’ll name two: Rebecca Clarke, a British composer and violist, born on August 27th of 1886, in Harrow, and Johan Pachelbel, the German composer, famous for his Cannon in D, but in reality, a prolific composer, whose Hexachordum Apollinis, a collection of keyboard music, deserves to be known better. He was born on September 1st of 1653 in Nuremberg.

August 27th of 1886, in Harrow, and Johan Pachelbel, the German composer, famous for his Cannon in D, but in reality, a prolific composer, whose Hexachordum Apollinis, a collection of keyboard music, deserves to be known better. He was born on September 1st of 1653 in Nuremberg.

If we turn to the performers and interpreters – instrumentalists, singers, and conductors – those are aplenty. Itzhak Perlman was born on August 31st of 1945 in Tel Aviv. Perlman is deservedly famous: from about the mid-1960s to the mid-1990s he was one of the greatest violinists to perform actively; he then narrowed his classical repertoire and branched out into klezmer and jazz, while also teaching and conducting. Some criticize his playing as too romantic, but we think that’s unfair: Perlman made hundreds of recordings, many excellent, some phenomenal. His Beethoven’s piano and violin sonatas and Brahm’s violin sonatas with Vladimir Ashkenazy are of the highest order. Here, for example, is the recording of Brahm’s Violin Sonata no. 1 made by Perlman and Ashkenazy in 1983.

famous: from about the mid-1960s to the mid-1990s he was one of the greatest violinists to perform actively; he then narrowed his classical repertoire and branched out into klezmer and jazz, while also teaching and conducting. Some criticize his playing as too romantic, but we think that’s unfair: Perlman made hundreds of recordings, many excellent, some phenomenal. His Beethoven’s piano and violin sonatas and Brahm’s violin sonatas with Vladimir Ashkenazy are of the highest order. Here, for example, is the recording of Brahm’s Violin Sonata no. 1 made by Perlman and Ashkenazy in 1983.

Three conductors were born this week, two Germans and one Hungarian who worked mostly in Germany. The native Germans are Wolfgang Sawallisch and Karl Böhm; the Hungarian is István Kertész. We’ve written about Böhm, one of the most important conductors of the 20th century but a deeply flawed personality, more than once, for example, here. Both Sawallisch and Kertész were born in the 1920s: Sawallisch in 1923, in Munich on August 26th, Kertész in 1929, in Budapest, on August 28th. Sawallisch took piano lessons as a child and continued his musical education at the Musikhochschule in Munich. As a young man, he fought in the German army during WWII and was captured by the British in Italy at the tail-end of it. At the age of 30 he conducted the Berlin Philharmonic, and at 34 became the youngest conductor to appear at Bayreuth, where he led the performance of Tristan und Isolde. In 1960, he became the principal conductor of the Vienna Symphony (not to be confused with the much more famous Vienna Philharmonic). For 20 years he was the music director of the Bavarian State Opera where he conducted 32 complete cycles of Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen. From 1993 to 2003 he was the music director of the Philadelphia Orchestra. He died in 2013, months shy of his 90th birthday.

István Kertész’s life was much shorter, he was only 43 when he drowned while swimming in the Mediterranean in Herzliya, a town next to Tel Aviv, in 1973. Kertész was Jewish, as were so many other Hungarian conductors: Fritz Reiner, Antal Doráti, Eugene Ormandy (born Jenő Blau), George Szell, Ferenc Fricsay (only his mother was Jewish but that was enough to be prosecuted in anti-Semitic Hungary), and Georg Solti. In 1944 most of Kertész’s relatives were deported to Auschwitz and killed there. Kertész survived, went to study at the Ferenc Liszt Academy when the war was over, and had some conducting assignments after graduation. He and his family left Hungary after the 1956 Uprising and settled in Germany. From 1958 to 1963 he was the music director of the Augsburg Opera, where he conducted a wide repertoire. At the same time, he guest-conducted many major European and American orchestras. In 1964, he assumed the same position with the Cologne Opera and also became the principal conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra. István Kertész had an unusually broad repertoire, both in opera and orchestral music. He conducted many major orchestras and was the first choice of the Cleveland musicians to replace the departing Geroge Szell (instead, Lorin Maazel was hired by the board).

Richard Tucker, a wonderful American tenor (also Jewish – we seem to have a Jewish theme today) was born on August 28th of 1913 in Brooklyn, NY. We’ll get back to him another time.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: August 19, 2024. Peri, Bernstein. Jacopo Peri, an Italian composer of the transitional period between the Renaissance and Baroque and author of the very first opera, Dafne, was born on August 20th of 1561. Last year we got involved with Peri, his contemporary Emilio de’ Cavalieri, and the process of transitioning from one, deeply established musical style to a very different one, a style that may be considered a “lesser” one, at least in its initial phase. We still find this process and the personalities involved very interesting. You may want to read about Peri and the period here, here, and here.

first opera, Dafne, was born on August 20th of 1561. Last year we got involved with Peri, his contemporary Emilio de’ Cavalieri, and the process of transitioning from one, deeply established musical style to a very different one, a style that may be considered a “lesser” one, at least in its initial phase. We still find this process and the personalities involved very interesting. You may want to read about Peri and the period here, here, and here.

Claude Debussy, one of the most influential composers of his time, was born in St. Germain-en-Laye on August 22nd of 1862. And when we say, “of his time,” we’re talking about one of the most fecund periods of classical music, the period from 1894, when Debussy composed Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune, till his death in 1918 at the age of 55. Just for reference, let’s take a look at who else was active during the period. Here’s what we see: Gustav Mahler, who, by the way, conducted the Prélude in New York in 1910, his whole output falls within this period; Sergei Rachmaninov, whose piano concertos no. 2 and no. 2?? were written in the first decade of the 20th century; much of Alexander Scriabin’s late works; Richard Strauss’s most important tone poems and operas such as Salome and Der Rosenkavalier, all fall within the period. Composers as different as Arnold Schoenberg, Ottorino Respighi, Manuel de Falla, and of course, Debussy’s younger contemporary and friend Maurice Ravel were all extremely productive during the same period. And still, Debussy’s star shines brightly. While his piano and orchestral works are probably among his most popular, he worked in many genres. Pelléas et Mélisande, premiered in 1902, is one of the most important operas of the 20th century. His chamber music is brilliant; he also wrote wonderful songs. We have quite a bit of Debussy’s music in our library, you may take a look here. A note on labeling: Debussy created a musical style, at some point called “Impressionism,” the label stuck; he hated the term, and so did Ravel, another “impressionist.”

Gustav Mahler, who, by the way, conducted the Prélude in New York in 1910, his whole output falls within this period; Sergei Rachmaninov, whose piano concertos no. 2 and no. 2?? were written in the first decade of the 20th century; much of Alexander Scriabin’s late works; Richard Strauss’s most important tone poems and operas such as Salome and Der Rosenkavalier, all fall within the period. Composers as different as Arnold Schoenberg, Ottorino Respighi, Manuel de Falla, and of course, Debussy’s younger contemporary and friend Maurice Ravel were all extremely productive during the same period. And still, Debussy’s star shines brightly. While his piano and orchestral works are probably among his most popular, he worked in many genres. Pelléas et Mélisande, premiered in 1902, is one of the most important operas of the 20th century. His chamber music is brilliant; he also wrote wonderful songs. We have quite a bit of Debussy’s music in our library, you may take a look here. A note on labeling: Debussy created a musical style, at some point called “Impressionism,” the label stuck; he hated the term, and so did Ravel, another “impressionist.”

It's said that Debussy influenced all composers of the 20th century except for Schoenberg. That is an exaggeration, but Debussy did influence many composers, from Stravinsky to Les Six and on. One composer also born this week who clearly wasn’t is Karlheinz Stockhausen. Some years ago we wrote: “In our library, we have three recordings of Karlheinz Stockhausen. Two of them are rated “one note,” the lowest rating that could be given. Considering that one piece is played by the pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard, we can safely assume that it’s not the performance that our listeners disliked but the pieces themselves. Stockhausen […] is considered one of the seminal composers of the second half of the 20th century. While we acknowledge the disapproval of some listeners, we think that his music is worth the effort, even if in small doses, and will continue bringing him up on occasion.” Since then, we added just one piece by Stockhausen, a composition called Kreuzspiel. It didn’t get rated, maybe nobody wanted to listen to it. The one-note ratings on older recordings still stand.

The great Leonard Bernstein was born on August 25th of 1918. Also, Lili Boulanger, whose life was tragically short, was born on August 21st of 1893; the Romanian composer and violinist George Enescu, born on August 19th of 1881; and a very interesting Austrian (and later American) composer Ernst Krenek, he was born on August 23rd of 1900. Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: August 12, 2024. Through the Centuries. This week covers four centuries of music: the oldest one, Heinrich Ignaz Biber, was born in 1644, and the most recent, Lucas Foss, in 1922 (he died in the 21st century, in 2009). There were too many in between, but we’ll mention some. Let’s start with Biber, a Bohemian-Austrian composer born on August 12th of 1644 in Wartenberg, Bohemia, then part of the Hapsburg Empire, now Stráž pod Ralskem in the Czech Republic. A highly reputable violinist, he was employed in courts of Graz, Olmütz (now Olomouc), Kremsier (now Kroměříž), and eventually, by the Archbishop of Salzburg, where one hundred years later Mozart would also be employed. Biber stayed in Salzburg for the rest of his life, eventually becoming the Kapellmeister. The finest or at least the most famous music composed by Biber was collected in his Mystery (sometimes called Rosary) Sonatas, in German Rosenkranzsonaten,15 short sonatas for the violin and continuo. Here’s the 3rd of the sonatas, The Nativity. Franzjosef Maier plays a Baroque violin; he’s accompanied by the organ, cello and theorbo, all of the Baroque era.

recent, Lucas Foss, in 1922 (he died in the 21st century, in 2009). There were too many in between, but we’ll mention some. Let’s start with Biber, a Bohemian-Austrian composer born on August 12th of 1644 in Wartenberg, Bohemia, then part of the Hapsburg Empire, now Stráž pod Ralskem in the Czech Republic. A highly reputable violinist, he was employed in courts of Graz, Olmütz (now Olomouc), Kremsier (now Kroměříž), and eventually, by the Archbishop of Salzburg, where one hundred years later Mozart would also be employed. Biber stayed in Salzburg for the rest of his life, eventually becoming the Kapellmeister. The finest or at least the most famous music composed by Biber was collected in his Mystery (sometimes called Rosary) Sonatas, in German Rosenkranzsonaten,15 short sonatas for the violin and continuo. Here’s the 3rd of the sonatas, The Nativity. Franzjosef Maier plays a Baroque violin; he’s accompanied by the organ, cello and theorbo, all of the Baroque era.

Two more composers were born in the 17th century this week: Nicola Porpora, in 1686, and Maurice Greene, in 1696. Porpora, born in Naples on August 17th of 1686, was one of the most important opera composers of the era, first challenging Alessandro Scarlatti in Naples, and then becoming Handel’s competitor in London. He was also a famous music teacher: his pupils included the castrati Farinelli and Caffarelli, and also Haydn. Porpora composed more than 50 operas, plus oratorios, cantatas and instrumental music. Here’s the aria In Amoroso Petto from Porpora’s opera Arianna In Nasso. Simone Kermes is the soprano, Vivica Genaux – the mezzo. Cappella Gabetta is conducted by Andrés Gabetta.

Maurice Green, born in London on August 12th of 1696 was an English composer known for his “anthems,” short sacred choral works. Lord, Let Me Know Mine End (here) is his most famous composition.

If three composers were born in the 17th century, only one comes from the 18th: Antonio Salieri, famous for all the wrong reasons. Three Frenchmen were born in the 19th century, Benjamin Godard, on August 18th of 1849, Gabriel Pierné, on August 16th of 1863, in Metz, and at the end of the century, on August 15th of 1890, Jacques Ibert. Of the three, Ibert seems to us to be the most interesting. The 20th century gave us only one composer, Lucas Foss. Foss was born in Berlin on August 15th of 1922 into a Jewish family (Benjamin Godard was also Jewish). Foss’s family left for Paris as soon as the Nazis came to power, and in 1937 they moved to the US. Foss was a prodigy, a talented composer, a lifelong friend of Leonard Bernstein, a teacher, music director and much more. We’ll write about him in detail next year.

PermalinkThis Week in Classical Music: August 5, 2024. Guillaume Dufay. Just last week we mentioned the troublesome fact regarding Early music composers, especially the pre-Renaissance ones: we practically never know their birthdays, and here comes a possible exception in the person of Guillaume Dufay: with some degree of certainty and based on existing documents, musicologists seem to have determined that he was born on August 5th of 1397. At a time when the individuality of the artists was often obscured and considered unimportant, Dufay was acknowledged as the greatest composer of his generation. Dufay, whose name during his time was written Du Fay, had a long and particularly eventful life. He was born in Beersel near Brussels and died at the age of 77 in Cambrai, on November 27th of 1474. As a boy, he studied at the Cathedral of Cambrai. His musical talents were acknowledged from an early age, and cathedral officials allowed Dufay to join the bishop of Cambrai’s retinue on his many travels. On one such trip, he was noticed by Carlo Malatesta, the ruler of Rimini, who brought Dufay to Italy sometime around 1420. He stayed in Rimini for about four years, returning to Cambrai in 1424. Two years later he was back in Italy, this time in Bologna, in the service of Cardinal Louis Aleman. His stay in Bologna was short, as in 1428 the Cardinal and his court, including Dufay, were expelled from the city. Dufay went to Rome, and, by then a well-known musician, he was hired by the papal chapel (choir). He served there till 1433, first to Pope Martin V, and after Martin’s death, to Pope Eugene IV. While in Rome, he asked for and received several “benefices,” clerical positions in churches that provided him with additional income. A large body of work is attributed to the years of Dufay’s sojourn in Rome. In 1434 Dufay joined the Court of Amédée VIII, the Duke of Savoy, then one of the most powerful duchies of Europe, which included not just the French territories by the same name but also Aosta and much of Piedmont in Italy. Again, his stay in Savoy was brief: one year later he was back in the service of Pope Eugene IV but this time in Florence, as, due to the extremely turbulent church politics, the pope was driven out of Rome. In 1437 the papal court moved to Bologna, and at about that time, Dufay received a very important benefice, the cannon’s position at the Cambrai Cathedral.

of Guillaume Dufay: with some degree of certainty and based on existing documents, musicologists seem to have determined that he was born on August 5th of 1397. At a time when the individuality of the artists was often obscured and considered unimportant, Dufay was acknowledged as the greatest composer of his generation. Dufay, whose name during his time was written Du Fay, had a long and particularly eventful life. He was born in Beersel near Brussels and died at the age of 77 in Cambrai, on November 27th of 1474. As a boy, he studied at the Cathedral of Cambrai. His musical talents were acknowledged from an early age, and cathedral officials allowed Dufay to join the bishop of Cambrai’s retinue on his many travels. On one such trip, he was noticed by Carlo Malatesta, the ruler of Rimini, who brought Dufay to Italy sometime around 1420. He stayed in Rimini for about four years, returning to Cambrai in 1424. Two years later he was back in Italy, this time in Bologna, in the service of Cardinal Louis Aleman. His stay in Bologna was short, as in 1428 the Cardinal and his court, including Dufay, were expelled from the city. Dufay went to Rome, and, by then a well-known musician, he was hired by the papal chapel (choir). He served there till 1433, first to Pope Martin V, and after Martin’s death, to Pope Eugene IV. While in Rome, he asked for and received several “benefices,” clerical positions in churches that provided him with additional income. A large body of work is attributed to the years of Dufay’s sojourn in Rome. In 1434 Dufay joined the Court of Amédée VIII, the Duke of Savoy, then one of the most powerful duchies of Europe, which included not just the French territories by the same name but also Aosta and much of Piedmont in Italy. Again, his stay in Savoy was brief: one year later he was back in the service of Pope Eugene IV but this time in Florence, as, due to the extremely turbulent church politics, the pope was driven out of Rome. In 1437 the papal court moved to Bologna, and at about that time, Dufay received a very important benefice, the cannon’s position at the Cambrai Cathedral.

While serving in Savoy and later at the papal court, Defay developed many valuable connections: with the Burgundy court, where he met another famous composer, Gilles Binchois, and with the Estes, Dukes of Ferrara. Ferrara was an important musical center, second only to the pope’s chapel; Defay visited the city in 1437.

Things were getting even more confusing in Italy, where in 1439 Pope Eugene IV was deposed and Defay’s former patron, Duke Amédée of Savoy was proclaimed Pope (or rather antipope) Felix V. To avoid problems with his warring benefactors, Defay left the papal court and returned to Cambrai, assuming the canonicate. That marked the beginning of the most stable period of Dufay’s life: he stayed in Cambrai for 11 years, till 1450. In 1449 Pope Felix V abdicated, and the politics of Rome calmed down; Dufay started traveling again. In 1450 he went to Turin, to visit Duke Amédée, no longer the Pope (Amédée died shortly after their meeting). In 1452 Dufay went to Savoy again and stayed there for six years, till 1458, this time at the service of Duke Louis

In 1558 Dufay returned to Cambrai and his position of the cannon. A famous composer, he was visited by many notables, including composers Ockeghem and Antoine Busnois. Among the more significant compositions of the period was his Requiem Mass, now lost, unfortunately. Dufay was buried in the Cambrai Cathedral, which was demolished during the French Revolution. His tombstone was later found and is now in a museum in Lille.

Here's Gloria, from Dufay’s Missa de San Anthonii de Padua. The Binshois Concort is directed by Andrew Krikman.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: July 29, 2024. Rott and Ingegneri. Hans Rott was born this week, on August 1st of 1858. This composer, who died at 25 and was mad for the last several years of his tragically short life, continues to fascinate us. Clearly, he was a major talent, and who knows how he would’ve developed, but even within the limited scope of his output, one can discern musical ideas Mahler would develop some years later. We’ve written about him several times, here, for example. We are also happy to report that his Symphony in E major is being performed and recorded more often, the latest time being in 2021 for Deutsche Grammophon with the excellent Jakub Hrůša leading the Bamberger Symphoniker.

years of his tragically short life, continues to fascinate us. Clearly, he was a major talent, and who knows how he would’ve developed, but even within the limited scope of his output, one can discern musical ideas Mahler would develop some years later. We’ve written about him several times, here, for example. We are also happy to report that his Symphony in E major is being performed and recorded more often, the latest time being in 2021 for Deutsche Grammophon with the excellent Jakub Hrůša leading the Bamberger Symphoniker.

There are many very talented composers of the Renaissance that we have never written about, for the only reason that their birthdays are unknown, so they fall outside of the framework of the “classical music this week.” One of these composers is Marc'Antonio Ingegneri. He’s mostly forgotten these days, unjustly so in our opinion. If he is remembered at all, it is as the teacher of the great Claudio Monteverdi, but in his days, he was the leading composer of Cremona, one of the musical centers of Italy.

Ingegneri was born in Verona in 1535 or 1536, which made him about 10 years younger than Palestrina, three years younger than Orlando di Lasso, and about the same age as Giaches de Wert. As is usually the case with the composers of that era, we know little about his early days. He was a choirboy at the Verona cathedral and probably took lessons from Vincenzo Ruffo, a noted composer, also a Veronese, who was active as a music reformer, implementing an edict of the Council of Trent which stated that words in church music should be legible, a requirement that almost killed the polyphonic mass. Ingegneri left Verona in his early 20s and for a while played the violin in the band of the Scuola Grande di San Marco in Venice. It’s likely that in the 1560s he went to Parma to study with Cipriano de Rore, one of the noted composers of the mid-16th century. Sometime around 1566, Ingegneri moved to Cremona and soon after had his Primo libro de madrigali a quattro voci published. He was active in the music-making at the Cremona Cathedral, and in 1580 was made the maestro di cappella. Sometime soon after he became the teacher of the young Monteverdi, who was born in Cremona and was at the time 15 or 16 years old. It’s clear that Ingegneri was famous outside of Cremona, as he dedicated books of madrigals to his patrons in Milan, Parma, Verona, and even Vienna. His music was published in many cities, such as Venice, Milan, Brescia, Ferrara and Rome. For about a decade from the mid-1570s to the mid-1580s Ingegneri composed mostly secular madrigals, but then reverted to church music. He was a good friend of bishop Nicolò Sfondrato, later Pope Gregory XIV who ruled the Catholic church for just 11 months. Ingegneri died in Cremona on July 1st of 1592.

Here is Ingegneri’s motet for the feast of the Assumption of Mary, Vidi speciosam. The Choir of Girton College, Cambridge, and the Historic Brass of Guildhall School are led by Gareth Wilson.Permalink