Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

This Week in Classical Music: November 25, 2024. A Busy Week. This week is full of interesting anniversaries, but unfortunately, we’re distracted by other things to give the composers and musicians born this week the attention they deserve. Therefore, we’ll limit ourselves to a simple list. Jean-Baptiste Lully, an Italian who became the most important composer of the early French Baroque, was born in Florence on November 28th of 1632. He was a favorite of Louis XIV, the Sun King, and Molière’s friend.

and musicians born this week the attention they deserve. Therefore, we’ll limit ourselves to a simple list. Jean-Baptiste Lully, an Italian who became the most important composer of the early French Baroque, was born in Florence on November 28th of 1632. He was a favorite of Louis XIV, the Sun King, and Molière’s friend.

Anton Stamitz, a son of Johann Stamitz and a brother of Carl Stamitz, all prominent composers, was born in Německý Brod, Bohemia, on November 27th of 1750. The family lived in Mannheim, where the father was instrumental in making the court orchestra into one of the best ensembles in Europe. Anton played in this orchestra (he was a virtuoso violinist). Here is his Concerto for Two Flutes & Orchestra in G major; Shigenori Kudo and Jean-Pierre Rampal are the flutes; Josef Schneider conducts the Salzburg Mozarteum Orchestra.

The great Italian master of the bel canto opera, Gaetano Donizetti was born in Bergamo on November 29th of 1797. He wrote about 70 operas; among his best are Anna Bolena, L'elisir d'amore, Maria Stuarda and Lucia di Lammermoor. Maria Callas brought Anna and Lucia to life like very few have done, before or after.

Ferdinand Ries was a minor composer, Beethoven’s pupil, friend, secretary and copyist, and, importantly, the person who commissioned Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Like his teacher, Ries was born in Bonn, on November 28th of 1784.

Three Russian composers were also born this week, all in November: Anton Rubinstein, on the 28th, in 1829, Sergei Taneyev, on the 25th, in 1856, and Sergey Lyapunov, on the 30th, in 1859. Rubinstein was not just a composer but also a brilliant pianist, second only to Liszt, and conductor. In 1862 he founded the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, the first one in Russia (his brother, Nikolai Rubinstein, also a pianist, composer and conductor, founded the Moscow Conservatory in 1866). Taneyev was Nikolai Rubinstein’s pupil at the Moscow Conservatory and Tchaikovsky’s close friend (Tchaikovsky dedicated the symphonic poem Francesca da Rimini to Taneyev). Lyapunov wrote, among other things, Twelve Transcendental Etudes (études d'exécution transcendente). Here’s the second of these etudes, "The Ghosts' Dance," played by Florian Noack.

And speaking of etudes of transcendental difficulty, Charles-Valentin Alkan, a French virtuoso pianist and composer, wrote many of them (Alkan was born in Paris on November 30th of 1813). Marc-André Hamelin, one of the most technically capable pianists of our time, is one of the few who can give Alkan’s music its due. Alkan, a French Jew, had an unusual and interesting life and we’ll dedicate a separate entry to him. Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: November 18, 2024. A Day Worth a Week. Here’s what happened on this day in classical music: In 1786, Carl Maria von Weber was born in Eutin, a small town not far from Lübeck. He’s famous as one of the first German Romantic composers, especially for his opera Der Freischütz. At his time, he was also known as a virtuoso pianist, conductor, and an important music critic, like E.T.A. Hoffmann around the same time and Robert Schumann a generation later. Here’s the Overture to Der Freischütz (The Freeshooter or The Marksman in English). Carlos Kleiber conducts the Staatskapelle Dresden.

small town not far from Lübeck. He’s famous as one of the first German Romantic composers, especially for his opera Der Freischütz. At his time, he was also known as a virtuoso pianist, conductor, and an important music critic, like E.T.A. Hoffmann around the same time and Robert Schumann a generation later. Here’s the Overture to Der Freischütz (The Freeshooter or The Marksman in English). Carlos Kleiber conducts the Staatskapelle Dresden.

Though not a musician himself, our next celebrated birthday is that of an essential part of the famous duo responsible for the best comic operas in English: the librettist and playwright William Schwenck (W.S.) Gilbert, in partnership with the composer Arthur Sullivan, created such comic masterpieces as H.M.S. Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance and The Mikado. Gilbert was born on this day in London in 1836. His partnership with Sullivan lasted 20 years and together they wrote 14 operas.

Ignacy Jan Paderewski¸ the Polish pianist, composer and statesman, was born on this day in a village of Kurilovka, then part of the Russian Empire, in 1860. Padarewski was one of the most famous pianists of his time, but during the Great War, he became a politician, joining the Polish National Committee in Paris: Poland, divided between Russia, Austria-Hungary, and Germany, didn’t exist as a state, and the National Committee pressed for the recognition of Poland once the war was over. Paderewski spoke to President Wilson, the Congress, and the leaders of France and the UK. More persuasive than any other Polish leader, he was instrumental in birthing Poland as a state. In January of 1919, he was appointed Prime Minister and the Minister of Foreign Affairs of this new state. In this capacity, he signed for Poland the Treaty of Versailles. He proved to be a poor administrator and resigned his premiership in December of 1919. He continued as the foreign minister till 1922 and then left politics for good, resuming his musical career. He returned to public life in 1939, after Germany (and then the Soviet Union) invaded Poland. He was made President of the Sejm (parliament) in exile in London. Paderewski died in New York in 1941.

Heinrich Schiff, a wonderful Austrian cellist, was also born on this day, in 1951. His performances of Bach’s unaccompanied cello pieces were peerless. All standard cello concertos were part of his repertoire; he also premiered several concertos of his contemporaries, like Henze and Richard Rodney Bennett. Schiff’s career was not very long: in 2010, when he was 60, he quit performing because of a consistent pain in his right shoulder. Schiff died in December of 2016.

And one more, and important, anniversary: the great conductor Eugene Ormandy was born on this day 125 years ago as Jenő Blau into a Jewish family in Budapest, then in Austria-Hungary. He started studying the violin at the age of three and entered the Royal National Hungarian Academy of Music when he was five, the youngest student ever. He emigrated to the US in 1921, and for the first several years played violin in small orchestras. He started conducting, sporadically, in 1927 and in 1931, almost by chance, led a Philadelphia Orchestra concert, substituting for Toscanini who fell ill. Following this successful performance, he was appointment the music director of the Minnesota Symphony. In 1936 he returned to Philadelphia to share the leadership of the orchestra with Stokowski, and two years later became their single music director, the position he held for the following 42 years, the longest tenure in any major US orchestra.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: November 11, 2024. Leonid Kogan. The Soviet Union was obsessed with rankings, which were applied (or assumed) in many areas. Within the power structures, there was of course, the one and only Secretary General of the Communist party; in city planning, Moscow was number one and treated differently than any other city. The same applied to the arts. There had to be a best ballerina (Ulanova first, then Plisetskaya), and even in music, the same rankings applied. After Stalin’s death, Shostakovich was officially considered the greatest living composer. There had to be pianist number one (Sviatoslav Richter), but also pianist number two (Emil Gilels), same for the violin or cello (Rostropovich as cellist number one, Daniil Shafran number two). The ranking among the violinists was this: David Oistrakh – number one, Leonid Kogan – number two. Oistrakh was, undisputable, a great violinist, but so was Kogan, and looking from the outside, these rankings look silly, but such was the nature of Sovietsociety, where fuzzy diversity – whether of ideas or tastes – was not welcome.

structures, there was of course, the one and only Secretary General of the Communist party; in city planning, Moscow was number one and treated differently than any other city. The same applied to the arts. There had to be a best ballerina (Ulanova first, then Plisetskaya), and even in music, the same rankings applied. After Stalin’s death, Shostakovich was officially considered the greatest living composer. There had to be pianist number one (Sviatoslav Richter), but also pianist number two (Emil Gilels), same for the violin or cello (Rostropovich as cellist number one, Daniil Shafran number two). The ranking among the violinists was this: David Oistrakh – number one, Leonid Kogan – number two. Oistrakh was, undisputable, a great violinist, but so was Kogan, and looking from the outside, these rankings look silly, but such was the nature of Sovietsociety, where fuzzy diversity – whether of ideas or tastes – was not welcome.

November 14th marks Leonid Kogan’s 100th anniversary. He was born into a Jewish family in Ekaterinoslav, now Dnepr, in Ukraine. He studied in Moscow, first in the Central Music school, then in the Conservatory, in both places with Abram Yampolsky, the great Russian violin teacher (Yampolsky was so taken by his talented pupil that, for a while, he housed him in his small apartment). Kogan’s virtuosity became obvious very early, but, unlike many young musicians, he also demonstrated deep insights into the music he played. At the age of 16 he played Brahm’s violin concerto, and at 20, while still a student at the conservatory, he was given the official position of a soloist at the Moscow Philharmonic Organization, the body responsible for managing the careers of professional musicians and organizing concerts not only in the capital but in many other cities of the country. With that, Kogan embarked on several tours of the Soviet Union. In 1947 he shared the first prize at the Prague youth competition, and in 1949 he played all of Paganini’s 24 Caprices in one evening. In 1951 he won the prestigious Queen Elisabeth competition in Brussels and in 1955 he was allowed to play concerts in Paris (at that time, only very few Soviet musicians were allowed to travel to Western Europe or the US, Sviatoslav Richter’s first tour, to the US, happened only in 1960). The Paris concerts were very successful, and Kogan, not well known in the West at the time since most of his recordings were made by the Soviet firm “Melodia” and unavailable outside the Iron Curtain, became famous. Other Western tours followed: South America in 1956, and then, in 1957-59, the tour of North America. As Howard Taubman wrote of his concert at Carnegie Hall, “He left no doubt of the exceptional subtlety and refinement of his art. If the men in the Kremlin will forgive the expression, Mr. Kogan played like an aristocrat.”

Kogan, who loved large-form pieces, also played chamber music. The Gilels-Kogan-Rostropovich trio performed for about 10 years and made numerous recordings. Kogan was married to Elizaveta Gilels, sister of pianist Emil Gilels and also a student of Abram Yampolsky. Kogan died of a heart attack on December 17th of 1982, age 58, just outside of Moscow while traveling by train to give a concert in a provincial city.

Brahm’s Violin concerto was one of Kogan’s favorites. He performed it often, with different orchestras, and many recordings are available, for example, two from 1967, one with the Moscow Philharmonic and another with the Philharmonia Orchestra of London, both conducted by Kirill Kondrashin. We like the one he made in 1959, even if its recording quality is not great. Again, Leonid Kogan plays with the Philharmonia Orchestra and again Kirill Kondrashin is conducting (here). Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: November 4, 2024. Couperin and performers. François Couperin, called “Le Grand” to distinguish him from the lesser but still talented members of his extended musical family, was born in Paris on November 10th of 1668 during the reign of Louis XIV. With Jean-Baptiste Lully and Jean-Philippe Rameau, Couperin was one of the three greatest French composers of the Baroque era and we have written about him on many occasions, for example here. The French culture of the period was in many ways indebted to Italy (and so was its food: Catherine de' Medici, the Italian wife of King Henry II and mother of kings Francis II, Charles IX, and Henry III, taught the French how to cook). Lully, a founding father of French classical music, was Italian by birth and a major influence on all French composers who followed him; Couperin was also influenced by Arcangelo Corelli. This of course in no way dеtracts from Couperin’s great talent and individuality, it is just a historical fact that music in Italy was much more developed than in late-17th century France. Interestingly, this relationship didn’t last long: the French music school continued developing, especially in the 19th and 20th centuries, whereas Italian music languished, except for opera. Couperin freely admitted the influence, pronouncing later in his life that he wanted to create a “union” between French and Italian music.

extended musical family, was born in Paris on November 10th of 1668 during the reign of Louis XIV. With Jean-Baptiste Lully and Jean-Philippe Rameau, Couperin was one of the three greatest French composers of the Baroque era and we have written about him on many occasions, for example here. The French culture of the period was in many ways indebted to Italy (and so was its food: Catherine de' Medici, the Italian wife of King Henry II and mother of kings Francis II, Charles IX, and Henry III, taught the French how to cook). Lully, a founding father of French classical music, was Italian by birth and a major influence on all French composers who followed him; Couperin was also influenced by Arcangelo Corelli. This of course in no way dеtracts from Couperin’s great talent and individuality, it is just a historical fact that music in Italy was much more developed than in late-17th century France. Interestingly, this relationship didn’t last long: the French music school continued developing, especially in the 19th and 20th centuries, whereas Italian music languished, except for opera. Couperin freely admitted the influence, pronouncing later in his life that he wanted to create a “union” between French and Italian music.

Couperin was famous as an organist and clavier player and wrote much for both instruments: he published four volumes of harpsichord music containing more than 200 pieces, many with very evocative titles but sometimes so vague that they remain poorly understood. He also published a book of organ music. We, on the other hand, will listen to one of his trio sonatas, which was not just influenced by but dedicated to Corelli. It’s called Le Parnasse ou L'Apothéose de Corelli and consists of seven movements. Each movement has a separate (and long) title, such as Corelli at the foot of Mount Parnassus asks the Muses to welcome him amongst them (movement 1) or Corelli, enchanted by his favorable reception at Mount Parnassus, expresses his joy. He proceeds with his followers (movement 2). It’s performed by the Musica Ad Rhenum (here).

Two pianists were born on November 5th, György Cziffra, whom we recently heard playing Liszt when we celebrated the composer’s birthday, in 1921, and Walter Gieseking, in 1895. A German, Gieseking excelled in playing the music of two French composers, Debussy and Ravel. And yet another musician was born on November 5th: the Hungarian-American violinist Joseph Szigeti, in 1892.

Also born this week: Ivan Moravec, a Czech pianist, on November 9th of 1930. Moravec studied with Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, traveled widely, even while Czechoslovakia was part of the Soviet bloc, and was known as a supreme interpreter of Chopin. Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: October 28, 2024. Dittersdorf. Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf, an Austrian with a funny-sounding name, was a serious composer. Born Carl Ditters in Vienna on November 2nd of 1739, he acquired the noble title “von Dittersdorf” years later, while serving at the court of the Prince-Bishop of Breslau. His full surname became Ditters von Dittersdorf and since then he has been known as Dittersdorf. As a child, Carl studied the violin, and as a boy of 11, he was recruited to the orchestra of Prince Sachsen-Hildburghausen, one of the best in Vienna. When the prince left Vienna and disbanded his orchestra, Carl found employment with Count Giacomo Durazzo, director of Burgtheater, the imperial court theatre. Ditters played in the Burgtheater orchestra and soloed, often playing his own violin concertos. By that time a recognized virtuoso and composer, he accompanied Christoph Willibald Gluck on a trip to Italy. In 1765 he left the Burgtheater to accept the position of Kapellmeister for the Bishop of Grosswardein, succeeding Michael Haydn, Franz Joseph’s younger brother. He stayed there for four years, composing orchestral music and operas for the court theater.

November 2nd of 1739, he acquired the noble title “von Dittersdorf” years later, while serving at the court of the Prince-Bishop of Breslau. His full surname became Ditters von Dittersdorf and since then he has been known as Dittersdorf. As a child, Carl studied the violin, and as a boy of 11, he was recruited to the orchestra of Prince Sachsen-Hildburghausen, one of the best in Vienna. When the prince left Vienna and disbanded his orchestra, Carl found employment with Count Giacomo Durazzo, director of Burgtheater, the imperial court theatre. Ditters played in the Burgtheater orchestra and soloed, often playing his own violin concertos. By that time a recognized virtuoso and composer, he accompanied Christoph Willibald Gluck on a trip to Italy. In 1765 he left the Burgtheater to accept the position of Kapellmeister for the Bishop of Grosswardein, succeeding Michael Haydn, Franz Joseph’s younger brother. He stayed there for four years, composing orchestral music and operas for the court theater.

In 1769, after the bishop got into legal troubles, Ditters found employment with Count Schaffgotsch, Prince-Bishop of Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland, at that time a part of Silesia). The prince lived in exile in the castle of Johannisberg and built a theater next to it. Ditters, for all purposes a Kapellmeister except for the title, was tasked with improving the court orchestra, hiring the singers, and composing operas. During that time (in 1772) Ditters’ employer successfully petitioned Empress Maria-Theresia to have Ditters ennobled; thus, he became “von Dittersdorf.” Through trials and tribulations (in 1778 Austrian politics forced the prince to flee Johannisberg, leaving the composer to administer part of his estate), Dittersdorf continued to manage the orchestra and compose. While Schaffgotsch was out of the picture, Dittersdorf offered some of his operas to Prince Esterházy, Haydn’s employer.

With the prince temporarily gone and musical life in Johannisberg in decline, Dittersdorf spent much of his time in Vienna. His oratorio Giob, the twelve symphonies, and the opera Der Apotheker und der Doktor (here is the Overture and the first scene) were all well received. In 1785, while in Vienna, he played a quartet with Franz Joseph Haydn, Mozart, and his pupil, Johann Baptist Wanhal (Dittersdorf played the first violin, Haydn the second violin, while Mozart played the viola). Dittersdorf returned to Johannisberg in 1787, but musical life there was in shambles. Dittersdorf attempted to find a position with Friedrich Wilhelm II of Prussia, who liked his music, but an offer never came. He was formerly dismissed from Johannisberg in 1785. By the end of his life, Dittersdorf, penniless and suffering from gout, continued to compose; some of his best work was written during those years. He died in 1779 in the castle of one of his patrons.

Dittersdorf was a prolific composer of concertos, operas, symphonies, oratorios and chamber music. Some of his concertos were written for unusual instruments: for example, there are four (!) concertos for the double bass. Let’s listen to one of them, Concerto no. 2 for Double Bass and orchestra. Ödön Rácz is the soloist, he plays with the Franz Liszt Chamber Orchestra. Permalink

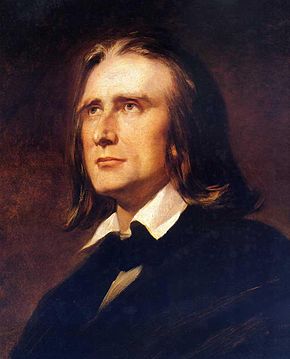

This Week in Classical Music: October 21, 2024. Lieberson and corrections. Last week our calendar got very much confused: we celebrated Franz Liszt, though his birthday, October 22nd, happens this week. There’s nothing wrong with celebrating Liszt early and often, so we’ll do it this week by playing one of his greatest compositions, the B minor Sonata. It’s a magnificent, grand Romantic piece, extremely popular in the early to mid-20th century when it was considered central to any virtuoso’s repertoire; it’s not played as often these days and its importance, so obvious before, is not as apparent. A one-movement piece, it is technically difficult and complex in structure. Liszt completed it in 1853 (the first sketches were written in 1842); it was premiered not by Liszt but Hans von Bülow, his student, in 1857. The sonata is dedicated to Robert Schumann, in return for Schumann dedicating his Fantasy in C major to Liszt some years earlier (Schumann died in 1856, between the Sonata’s completion and its premier). There are scores of excellent performances of the Sonata, so it’s nearly impossible to select the “best” one. Some recordings are more popular than others, for example, Krystian Zimerman’s from 1990 (and it’s indeed very good). And so are the recordings by Martha Argerich, Yuja Wang and Marc-André Hamelin. We’ll play an older recording, made live by the great pianist Sviatoslav Richter. He played it at the Aldeburgh Festival on June 21st of 1966 in the Aldeburgh parish church. We think it’s a profound performance.

happens this week. There’s nothing wrong with celebrating Liszt early and often, so we’ll do it this week by playing one of his greatest compositions, the B minor Sonata. It’s a magnificent, grand Romantic piece, extremely popular in the early to mid-20th century when it was considered central to any virtuoso’s repertoire; it’s not played as often these days and its importance, so obvious before, is not as apparent. A one-movement piece, it is technically difficult and complex in structure. Liszt completed it in 1853 (the first sketches were written in 1842); it was premiered not by Liszt but Hans von Bülow, his student, in 1857. The sonata is dedicated to Robert Schumann, in return for Schumann dedicating his Fantasy in C major to Liszt some years earlier (Schumann died in 1856, between the Sonata’s completion and its premier). There are scores of excellent performances of the Sonata, so it’s nearly impossible to select the “best” one. Some recordings are more popular than others, for example, Krystian Zimerman’s from 1990 (and it’s indeed very good). And so are the recordings by Martha Argerich, Yuja Wang and Marc-André Hamelin. We’ll play an older recording, made live by the great pianist Sviatoslav Richter. He played it at the Aldeburgh Festival on June 21st of 1966 in the Aldeburgh parish church. We think it’s a profound performance.

The American composer Peter Lieberson was born on October 26th of 1946 in New York. He studied composition with Milton Babbitt and Charles Wuorinen, some of the most “modernist” of American composers but his own music is much more tuneful. Lieberson wrote several concertos (three for the piano, one each for the horn, viola, and cello), an opera, and many chamber pieces, but he’s best remembered for his two song cycles, Rilke Songs for mezzo-soprano and piano, composed in 2001 and, from 2005, Neruda Songs for mezzo and orchestra. Both cycles were written for his wife, the wonderful mezzo Loraine Hunt Lieberson. Here, from the Rilke cycle, O ihr Zärtlichen (Oh you, tender ones). Loraine Hunt Lieberson is accompanied by Peter Serkin. And here is another song from the same cycle, Atmen, du unsichtbares Gedicht! (Breathe, you invisible poem!). It’s performed by the same artists.

Loraine Hunt Lieberson died from breast cancer in 2006 at the age of 52. Shortly after her death, Peter Lieberson was diagnosed with lymphoma. He continued to compose till the end of his life. Peter Lieberson died on April 23rd of 2011. Permalink