Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

This Week in Classical Music: November 16, 2020. Hindemith at 125. Paul Hindemith was born on November 16th of 1895 in Hanau, near Frankfurt. We’ll pick up where we left off four years ago when we wrote about his life until about 1923. He was then living in Frankfurt, already well known both as a composer and a violist (he organized the Amar Quartet where he played the viola), performing in Salzburg and working at the new music Donaueschingen Festival. (A brief note about the festival: it was organized in 1921, it’s the oldest and probably the most prestigious festival of contemporary music in existence, and Hindemith’s music was played there during its first season). Hindemith also got married to an actress and singer named Gertrud Rottenberg; Gertrud came from a prominent Frankfurt family (her grandfather was the mayor of Frankfurt) and was partly Jewish, which affected Hindemith’s life later in the 1930s. In 1927 he was invited to teach at the Berlin Musikhochschule. He soon decided that teaching composition is impossible, and that only the craft of handling music material could be taught. Lacking suitable textbooks, he embarked on leaning Latin and mathematics in order to be able to read old musical manuals. In 1929 Hindemith left the Amar Quartet and founded a string trio with Josef Wolfstahl, who a year later was replaced by Szymon Goldberg, then the concertmaster of the Berlin Philharmonic, and the celebrated cellist Emanuel Feuermann; thus in the early thirties Hindemith was playing in a trio with two Jewish musicians. Hindemith was not a man of the Left, he didn’t share political views of the likes of Bertolt Brecht, Hanns Eisler or Kurt Weill, but when the Nazis came to power in 1933, they nonetheless declared most of Hindemith’s music “cultural Bolshevism.” His trio could no longer perform in Germany, only abroad, and his Jewish colleagues at the Hochschule lost their jobs. Initially, Hindemith thought that this descent into extreme radicalism i was temporary, that another cycle of elections would change everything back to normal – but there were no free elections to come. Hindemith embarked on writing a major composition, the opera Mathis der Maler, for which he wrote his own libretto. The protagonist of the opera is a historical figure, the painter Matthias Grünewald, famous for his incredible Isenheim Altarpiece. In 1934, at Furtwängler’s request, he composed a symphony based on the opera. The premier in Berlin was a huge success, but it only led to more attacks from the Nazis. Hindemith started thinking about emigration; at the same time he asked Furtwängler to intervene with Hitler on his behalf: he wanted Furtwängler to invite Hitler to a composition class of his. Furtwängler did write an open letter in support of Hindemith, it was published in Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, a major newspaper of the day, in November of 1934. The letter was met with more derision from the Nazis, especially the Nazi “theoretician” Alfred Rosenberg and Joseph Goebbels, the propaganda minister. In 1935 Hindemith was invited by the Turkish government to advise them on the musical life of the country. Subsequently, he visited Turkey in 1936 and 1937. The establishment of the Ankara State Conservatory owes much to Hindemith. In 1936 the Nazis announced a total ban on Hindemith’s music. A year later Hindemith resigned from the Berlin Hochschule and traveled to the US for the first time. He emigrated to Switzerland in September of 1938 and in February of 1940 moved to the US.

years ago when we wrote about his life until about 1923. He was then living in Frankfurt, already well known both as a composer and a violist (he organized the Amar Quartet where he played the viola), performing in Salzburg and working at the new music Donaueschingen Festival. (A brief note about the festival: it was organized in 1921, it’s the oldest and probably the most prestigious festival of contemporary music in existence, and Hindemith’s music was played there during its first season). Hindemith also got married to an actress and singer named Gertrud Rottenberg; Gertrud came from a prominent Frankfurt family (her grandfather was the mayor of Frankfurt) and was partly Jewish, which affected Hindemith’s life later in the 1930s. In 1927 he was invited to teach at the Berlin Musikhochschule. He soon decided that teaching composition is impossible, and that only the craft of handling music material could be taught. Lacking suitable textbooks, he embarked on leaning Latin and mathematics in order to be able to read old musical manuals. In 1929 Hindemith left the Amar Quartet and founded a string trio with Josef Wolfstahl, who a year later was replaced by Szymon Goldberg, then the concertmaster of the Berlin Philharmonic, and the celebrated cellist Emanuel Feuermann; thus in the early thirties Hindemith was playing in a trio with two Jewish musicians. Hindemith was not a man of the Left, he didn’t share political views of the likes of Bertolt Brecht, Hanns Eisler or Kurt Weill, but when the Nazis came to power in 1933, they nonetheless declared most of Hindemith’s music “cultural Bolshevism.” His trio could no longer perform in Germany, only abroad, and his Jewish colleagues at the Hochschule lost their jobs. Initially, Hindemith thought that this descent into extreme radicalism i was temporary, that another cycle of elections would change everything back to normal – but there were no free elections to come. Hindemith embarked on writing a major composition, the opera Mathis der Maler, for which he wrote his own libretto. The protagonist of the opera is a historical figure, the painter Matthias Grünewald, famous for his incredible Isenheim Altarpiece. In 1934, at Furtwängler’s request, he composed a symphony based on the opera. The premier in Berlin was a huge success, but it only led to more attacks from the Nazis. Hindemith started thinking about emigration; at the same time he asked Furtwängler to intervene with Hitler on his behalf: he wanted Furtwängler to invite Hitler to a composition class of his. Furtwängler did write an open letter in support of Hindemith, it was published in Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, a major newspaper of the day, in November of 1934. The letter was met with more derision from the Nazis, especially the Nazi “theoretician” Alfred Rosenberg and Joseph Goebbels, the propaganda minister. In 1935 Hindemith was invited by the Turkish government to advise them on the musical life of the country. Subsequently, he visited Turkey in 1936 and 1937. The establishment of the Ankara State Conservatory owes much to Hindemith. In 1936 the Nazis announced a total ban on Hindemith’s music. A year later Hindemith resigned from the Berlin Hochschule and traveled to the US for the first time. He emigrated to Switzerland in September of 1938 and in February of 1940 moved to the US.

Here’s Hindemith’s Symphony Mathis der Maler, performed by London Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Jascha Horenstein.Permalink

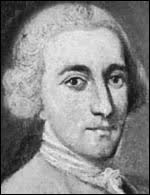

This Week in Classical Music: November 9, 2020. Couperin and Borodin. François Couperin, the great French composer, harpsichordist and organist of the Baroque era, was born in Paris on November 10th of 1668. He was a member of an incredible musical dynasty, which flourished from the late 16th century to the mid-19th, or more than 250 years. His family came from Chaumes-en-Brie, a town in the Brie region famous for its cheese, and that’s where several generations of Couperins were born, even though all of them would then move to work in Paris; François was the first one to be born in Paris (there was at least one other, older, composer François Couperin, so to distinguish them, in France “our” Couperin is called Le Grand (the Great). Probably the most famous of François’s ancestors was Louis Couperin, born in 1626, who was also a viol and keyboard player. He was presented to the court of the young Louis XIV and was the first one to be appointed the organist at the church of St. Gervais; eight members of the Couperin family served as organists there, including François Le Grand, the last one serving till 1826. You can read more about François Couperin here.

Paris on November 10th of 1668. He was a member of an incredible musical dynasty, which flourished from the late 16th century to the mid-19th, or more than 250 years. His family came from Chaumes-en-Brie, a town in the Brie region famous for its cheese, and that’s where several generations of Couperins were born, even though all of them would then move to work in Paris; François was the first one to be born in Paris (there was at least one other, older, composer François Couperin, so to distinguish them, in France “our” Couperin is called Le Grand (the Great). Probably the most famous of François’s ancestors was Louis Couperin, born in 1626, who was also a viol and keyboard player. He was presented to the court of the young Louis XIV and was the first one to be appointed the organist at the church of St. Gervais; eight members of the Couperin family served as organists there, including François Le Grand, the last one serving till 1826. You can read more about François Couperin here.

A fine Russian composer Alexander Borodin was born on November 12th of 1833. If he were less of a chemist and more of a composer, we might have enjoyed more of his music, but even as an occasional composer he created a masterpiece, the opera Prince Igor though he left it unfinished (Rimsky-Korsakov and Glazunov completed the orchestration). His symphonies, especially Symphony no 2, and the symphonic piece In the Steppes of Central Asia are fine works and so are his many art songs and some piano pieces. Here’s more about this unusual composer. Also, Aaron Copland, one of the most significant American composers of the 20th century was born 120 years ago, on November 14th of 1900 in Brooklyn, New York.

Two Russian string players were born on November 14th: the violinist Leonid Kogan in 1924 and the cellist Natalia Gutman in 1942. Kogan is rightly considered one of the greatest violinists of the 20th century. He was born in Dnepropetrovsk (now Dnipro, Ukraine) into a Jewish family. He moved to Moscow to study with the famed violin teacher Abram Yampolsky. Kogan started widely performing at the age of 17. In 1951 he won the Queen Elizabeth Competition. In 1955 Leonid Kogan made his debuts in Paris and London and in 1957 – in the US. He has taught at the Moscow Conservatory since 1952. In the 1950s Kogan, Emil Gilels and Mstislav Rostropovich formed a very successful trio (Kogan and Gilels collaborated often, and Kogan married Emil’s sister, Elisaveta). Here’s the recording of Bach’s Chaconne from Partita no.2 in D minor BWV 1004 made live in 1954.

Natalia Gutman was born in Kazan, Russia. At the Moscow Conservatory she studied with Galina Kozolupova and Mstislav Rostropovich. She and her husband, the violinist Oleg Kagan, were friends with Sviatoslav Richter; they played together in many concerts.Permalink

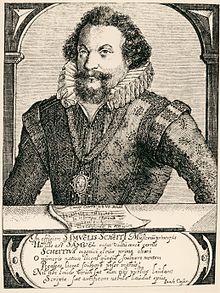

This Week in Classical Music: November 2, 2020. Scheidt, Bellini and two Pianists. Samuel Scheidt, one of the three German composers of the early Baroque (the other two being the better known Heinrich Schütz and Johann Hermann Schein) was born in Halle on November 3rd of 1587. All three of them were born withing two years of each other and worked together; Scheidt was the godfather to one of Schein’s daughters, while Schütz and Schein were good friends. Around 1607 Scheidt went to Amsterdam to study with the famous Dutch composer Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck. Upon his return to Halle, Scheidt was appointed the court organist to the Margrave of Brandenburg. At that time Michael Praetorius was the official court Kapellmeister but he was mostly absent, working in Dresden; Scheidt would have an opportunity to work with him in 1616, and two years later, in 1618, with both Praetorius and Schütz. In 1620 Scheidt himself was appointed Kapellmeister. Around that time, he composed a collection of motets called Cantiones sacrae. Here’s one of them, Das alte Jahr vergangen ist, performed by the ensemble Vox Luminis, directed by Lionel Meunier. This was a very productive time for Scheidt but things changed soon. The Thirty-Year War was raging and in 1625 it reached Halle. The city suffered terribly, changing hands several time between the warrying parties. By the end of the war half of the population was either dead or had left the city. Scheidt, who through all these years had stayed in Halle, retained his position of Kapellmeister but wasn’t paid. Practically penniless, he continued composing. At some point the city created a position of director musices for him, but even that didn’t last long. Another tragedy struck in 1636 when the plague killed all four of his surviving children within a month. In 1638, as the war was over, August, the Duke Elector of Saxony, moved to Halle and thus revived the court. Scheidt continued composing and publishing new music, much of it for the organ. His final composition was a collection of 100 organ chorales, published in 1650. Samuel Scheidt died in Halle on March 24th of 1654.

known Heinrich Schütz and Johann Hermann Schein) was born in Halle on November 3rd of 1587. All three of them were born withing two years of each other and worked together; Scheidt was the godfather to one of Schein’s daughters, while Schütz and Schein were good friends. Around 1607 Scheidt went to Amsterdam to study with the famous Dutch composer Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck. Upon his return to Halle, Scheidt was appointed the court organist to the Margrave of Brandenburg. At that time Michael Praetorius was the official court Kapellmeister but he was mostly absent, working in Dresden; Scheidt would have an opportunity to work with him in 1616, and two years later, in 1618, with both Praetorius and Schütz. In 1620 Scheidt himself was appointed Kapellmeister. Around that time, he composed a collection of motets called Cantiones sacrae. Here’s one of them, Das alte Jahr vergangen ist, performed by the ensemble Vox Luminis, directed by Lionel Meunier. This was a very productive time for Scheidt but things changed soon. The Thirty-Year War was raging and in 1625 it reached Halle. The city suffered terribly, changing hands several time between the warrying parties. By the end of the war half of the population was either dead or had left the city. Scheidt, who through all these years had stayed in Halle, retained his position of Kapellmeister but wasn’t paid. Practically penniless, he continued composing. At some point the city created a position of director musices for him, but even that didn’t last long. Another tragedy struck in 1636 when the plague killed all four of his surviving children within a month. In 1638, as the war was over, August, the Duke Elector of Saxony, moved to Halle and thus revived the court. Scheidt continued composing and publishing new music, much of it for the organ. His final composition was a collection of 100 organ chorales, published in 1650. Samuel Scheidt died in Halle on March 24th of 1654.

Vincenzo Bellini was also born this week, on November 3rd of 1801. You can read more about him here, the entry also contains information about Samuel Scheidt’s teacher, Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck. And then there was a composer whose name, according to Stephen Fry, is a good contender for the “Best name not just in music but in all history”: Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf. Hard to argue with Fry on this one. Von Dittersdorf was born in Vienna on November 2nd of 1739. He was a prolific composer, knew both Haydn and Mozart, and some of his concertos are very pleasant.

Finally, two wonderful pianists were born on November 5th: Walter Gieseking in 1895 and György Cziffra in 1921.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: October 26, 2020. Singers of the past. Two Italian singers, Giuditta Pasta, possibly the greatest soprano of the first half of the 19th century, and a legendary contralto castrato and Handel’s favorite, Senesino, were born this week. Giuditta Pasta was born in Saronno, near Milan, on October 26th of 1797. She made her debut in Milan at the age of 19, and soon after appeared in Paris’s Théâtre Italien; she sung Donna Elvira in Mozart’s Don Giovanni and several contemporary Italian operas. Her greatest Paris triumph was the role of Desdemona in Rossini’s Otello; she later repeated that success in London. She was Rossini’s favorite singer, making his operas Tancredi and Elisabetta, regina d'Inghilterra famous around Europe. Both Donizetti and Bellini wrote their greatest operas for Pasta: she premiered as Imogene in Il pirate, Amina in La sonnambula and Norma for Bellini; and for Donizetti she sung the title roles in Anna Bolena and Ugo, conte di Parigi. Stendhal was mad about Pasta and encouraged other composers to write for her. Pasta’s voice was what is known as soprano sfogato, naturally a mezzo-soprano which extends into the coloratura soprano range. Maria Callas’s voice was also soprano sfogato, that’s one reason musicologists often compare the two. The painting above was made by the 19th century Russian artist Karl Bryullov, who lived for years in Italy and painted portraits of many famous singers of the time.

in Saronno, near Milan, on October 26th of 1797. She made her debut in Milan at the age of 19, and soon after appeared in Paris’s Théâtre Italien; she sung Donna Elvira in Mozart’s Don Giovanni and several contemporary Italian operas. Her greatest Paris triumph was the role of Desdemona in Rossini’s Otello; she later repeated that success in London. She was Rossini’s favorite singer, making his operas Tancredi and Elisabetta, regina d'Inghilterra famous around Europe. Both Donizetti and Bellini wrote their greatest operas for Pasta: she premiered as Imogene in Il pirate, Amina in La sonnambula and Norma for Bellini; and for Donizetti she sung the title roles in Anna Bolena and Ugo, conte di Parigi. Stendhal was mad about Pasta and encouraged other composers to write for her. Pasta’s voice was what is known as soprano sfogato, naturally a mezzo-soprano which extends into the coloratura soprano range. Maria Callas’s voice was also soprano sfogato, that’s one reason musicologists often compare the two. The painting above was made by the 19th century Russian artist Karl Bryullov, who lived for years in Italy and painted portraits of many famous singers of the time.

Senesino was born Francesco Bernardi on October 31st of 1686 in Siena. He was castrated late, at the age of 13. Senesino started his career in Venice in 1707 and soon was singing in all major opera houses of Italy – in Bologna, Florence, Rome and Naples. By 1717 he was internationally famous, commanding large fees. In 1720 Handel hired him for his Royal Academy opera company for an enormous sum of 3,000 guineas a year (that’s £3,150; according to the Old Baily site, at that time “the First Lord of the Treasury enjoyed an annual salary of £4,000”). Senesino’s first performance in London was Giovanni Bononcini’s opera Astarto; it was a great success. Much success followed: he performed in all 32 operas produced by the company. These included 13 operas by Handel and eight by Bononcini. Senesino stayed with the company till it closed in 1728. He then left for Siena, where he built a fine house. Even though Handel and Senseino quarreled quite often, in 1730 the composer hired Senesino again for the resurrected (Second) Academy, this time for “only” 1,400 guineas a year. Apparently Senesino’s popularity didn’t diminish, though the relationship between him and Handel got worse and eventually Senesino quit the Royal Academy and, with the financial help of wealthy music lovers, created a new company, the Opera of the Nobility. Senesino, Farinelli and the soprano Francesca Cuzzoni were the lead singers, while Nicola Porpora – their chief composer. He stayed with the company till 1736. Senesino then moved to Italy; his last performances were in Porpora’s Il trionfo di Camilla at the Teatro San Carlo in Naples in 1740. Senesino died on January 27th of 1759. According to contemporary music critics, his voice was powerful and clear, with great diction and intonation. As a contralto he was unsurpassed; many Londoners preferred him to Farinelli. Handel composed 17 roles for him. But age wasn’t kind to Senesino: Horace Walpole, the English writer and art historian, met him late in his life, as Senesino was returning to Siena in a chaise: “We thought it a fat old woman; but it spoke in a shrill little pipe, and proved itself to be Senesini.”Permalink

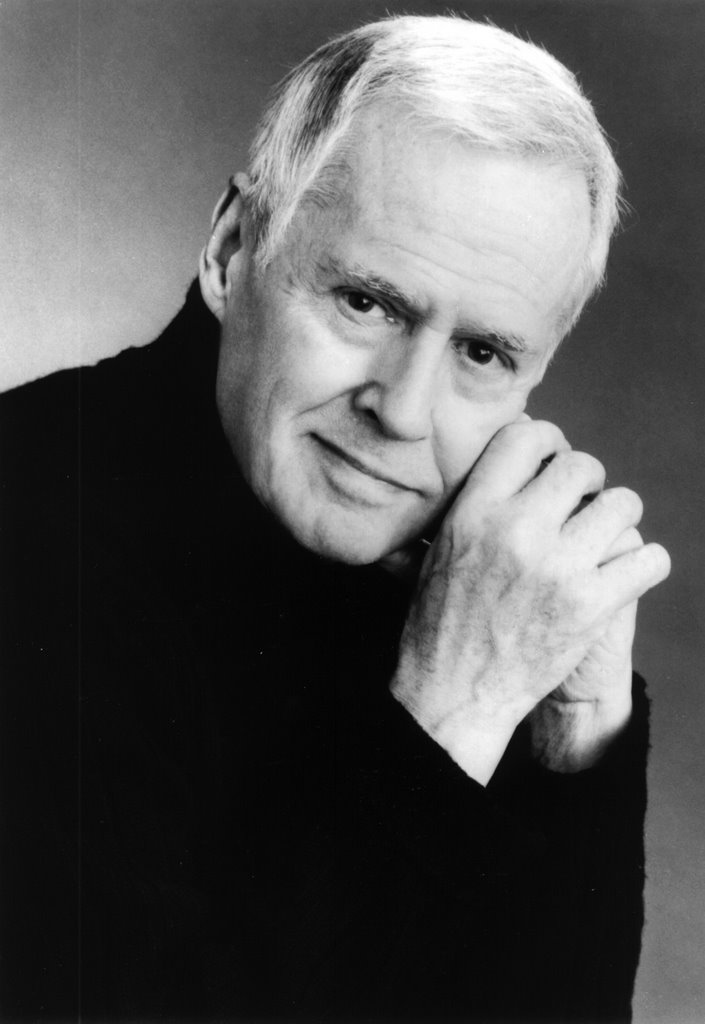

This Week in Classical Music: October 19, 2020. Liszt, etc. Good news: Ned Rorem is still with us and on October 23rd he will turn 97. Rorem may be better known for his revealing diaries, The Paris Diary of Ned Rorem, published in 1966, in which he described his own gay life and his relationships with many well-known personalities, in what would these days be considered “outing”, but he is also a fine composer. Rorem is at his best in art songs and is rightly famous for them. Here’s his song The Lordly Hudson on a text by Paul Goodman; it was called “the best song of 1948” and indeed it’s lovely (the mezzo-soprano Susan Graham is accompanied by Malcolm Martineau). In addition to hundreds of songs, Rorem’s output includes more than a dozen operas, which are rarely performed these days, several symphonies, and some very good chamber music. To quote from Alex Ross’s 2003 New Yorker essay on Rorem: “The Fourth Quartet, which the Emerson Quartet recently played at Zankel Hall, includes a once-in-a-lifetime movement called “Self Portrait,” in which the cello holds forth in a rambling, halting chant while the three other strings play frigid chords around it.” Here is the very Movement VIII, Self Portrait, from Rorem’s Quartet no. 4. It was recorded by the same Emerson String Quartet but several years earlier than when Ross heard it in 1997.

diaries, The Paris Diary of Ned Rorem, published in 1966, in which he described his own gay life and his relationships with many well-known personalities, in what would these days be considered “outing”, but he is also a fine composer. Rorem is at his best in art songs and is rightly famous for them. Here’s his song The Lordly Hudson on a text by Paul Goodman; it was called “the best song of 1948” and indeed it’s lovely (the mezzo-soprano Susan Graham is accompanied by Malcolm Martineau). In addition to hundreds of songs, Rorem’s output includes more than a dozen operas, which are rarely performed these days, several symphonies, and some very good chamber music. To quote from Alex Ross’s 2003 New Yorker essay on Rorem: “The Fourth Quartet, which the Emerson Quartet recently played at Zankel Hall, includes a once-in-a-lifetime movement called “Self Portrait,” in which the cello holds forth in a rambling, halting chant while the three other strings play frigid chords around it.” Here is the very Movement VIII, Self Portrait, from Rorem’s Quartet no. 4. It was recorded by the same Emerson String Quartet but several years earlier than when Ross heard it in 1997.

Franz Liszt was born this week, on October 22nd of 1811, and so was another classical composer, Georges Bizet, on October 25th of 1838. Bizet was 36 when Carmen premiered at the Opéra-Comique on March 3rd of 1875. As the final curtain fell, it was greeted with silence by the shocked and scandalized audience. Music critics panned it. The opera was still being staged when on June 3rd of that year, during the 32nd performance, Bizet died (two days earlier Bizet, who suffered from many ailments, including acute tonsillitis, inexplicably took a swim in the Seine; he fell gravely ill right after and died of a heart attack). His death was probably a reason for the public’s renewed interest in the opera. Almost immediately, Carmen became a sensation and to this day continues to be the most often staged French opera.

Two modernist composers were also born this week, the American Charles Ives, on October 20th of 1874 and the Italian, Luciano Berio, on October 24th of 1925. You can read more about them here and here. And finally, two wonderful Soviet pianist, friends and rivals, Emil Gilels and Yakov Flier: they were born two days and four years apart, Gilels on October 19th of 1916, Flier – on the 21st of the month, in 1912.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: October 12, 2020. Galuppi, Marenzio, Pavarotti. Baldassare Galuppi was born on October 18th of 1706. Last year we published a detailed entry about this rather underrated late Baroque Italian composer (here). Though he was mostly known for his operas, one of his major works was Messa per San Marco composed in 1766. Here’s the first movement, Gloria in excelsis Deo. Vocal Concert Dresden is conducted by Peter Kopp.

rather underrated late Baroque Italian composer (here). Though he was mostly known for his operas, one of his major works was Messa per San Marco composed in 1766. Here’s the first movement, Gloria in excelsis Deo. Vocal Concert Dresden is conducted by Peter Kopp.

The English composer Ralph Vaughan Williams was born on this day in 1872. We know that he’s considered one of the best British symphonists of the early 20th century and is much beloved in that country. Unfortunately, we cannot share the sentiment. The German composer Alexander von Zemlinsky was also born this week. We cannot do better than this. Also, Luca Marenzio, one of the best madrigalists on the late 16th century, was born on October 18th of 1553. Here’s one of his madrigals, Talchè Dovunque Vò, Tutte Repente, performed by the ensemble Concerto Italiano under the direction of Rinaldo Alessandrini.

Two fine American pianists were born this week, Gary Graffman on October 14th of 1928 and Stephen Kovacevich – on October 17th of 1940. Graffman studied at the Curtis Institute, and privately, with Horowitz and Rudolph Serkin; he won the Leventritt competition in 1949 and had a brilliant early career. Then, in 1979, his right hand became disabled, probably from focal dystonia, an ailment that afflicted Graffman’s close friend and another a brilliant pianist, Leon Fleisher. Stephen Kovacevich was born on October 17th of 1940. No, he is not famous for being Martha Argerich’s third husband: Kovacevich is a wonderful pianist in his own right. His recordings of Beethoven’s late sonatas Diabelli Variations are of the highest quality and were acknowledged as such by many music critics.

And finally, Luciano Pavarotti. He would’ve been 85 today: he was born on October 12th of 1935 in Modena. Here’s what we wrote about him a year ago. Pavarotti had probably the most beautiful lyrical tenor since Beniamino Gigli. Surely, you’ve heard Libiamo, ne’ lieti calici, from Verdi’s La Traviata, many times, but who does it better than Pavarotti? Here, from 1976, he’s singing Libiamo with his great partner, Dame Joan Sutherland. Richard Boning is conducting the National Philharmonic Orchestra (in case you’re wondering: the National Philharmonic was not a “real” orchestra, it was created solely for recording purposes; the musicians all came from major London orchestras).Permalink