Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

This Week in Classical Music: June 1, 2020. Argerich. Our apologies to the devotees of the music of Georg Muffat, if there are any. We’re not going to write about him, even though his birthday is today (he was born in 1653); however, you can check our earlier entries about him here and here. Neither will we write about Mikhail Glinka, also born on this day, in 1804, Edward Elgar, born June 2nd of 1857 and beloved by the English, or Aram Khachaturian, the pride of the Armenians. Khachaturian was born on June 6th of 1903 in Tbilisi into an Armenian family; Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, had a large Armenian population at the time. He eventually moved to Moscow and lived there for the rest of his life and only visited Armenia on several occasions. He was affected by the Armenian folk tunes, though, which he loved and collected on his trips to Armenia; his ballet Gayane, written around 1939, incorporated many of them. Khachaturian died in Moscow in 1978 but was buried in Yerevan, in the Komitas Pantheon of great Armenians.

here and here. Neither will we write about Mikhail Glinka, also born on this day, in 1804, Edward Elgar, born June 2nd of 1857 and beloved by the English, or Aram Khachaturian, the pride of the Armenians. Khachaturian was born on June 6th of 1903 in Tbilisi into an Armenian family; Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, had a large Armenian population at the time. He eventually moved to Moscow and lived there for the rest of his life and only visited Armenia on several occasions. He was affected by the Armenian folk tunes, though, which he loved and collected on his trips to Armenia; his ballet Gayane, written around 1939, incorporated many of them. Khachaturian died in Moscow in 1978 but was buried in Yerevan, in the Komitas Pantheon of great Armenians.

The artist we’d like to celebrate today is Martha Argerich, one of most spectacular pianists of the last 50 years. Martha, whose name is correctly pronounced “Marta Arkheritch” was born on June 5th of 1941 in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Her father’s ancestors came from Catalonia, Spain, while her mother’s grandparents were Russian Jews who came to Argentina to settle in the Colonia Villa Clara, established by the Jewish Colonization Association and supported by Baron Maurice de Hirsch, a Jewish philanthropist. Martha started playing the piano at the age of three and gave her first concert when she was eight, performing Mozart’s Piano Concerto no. 20, Beethoven’s First Piano Concerto and Bach’s French Suite no. 5. The family moved to Vienna when Martha was 14. There she studied with Friedrich Gulda; later she would work with a number of outstanding pianists and teachers: Stefan Askenase, Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, Madeleine Lipatti, the widow of Dinu Lipatti, Abbey Simon and Nikita Magaloff. At the age of 16 Martha won first prizes in the 1957 Busoni and Geneva international competitions. Then, in 1965 she won the first prize in the Chopin Competition in Warsaw; her playing created a sensation. Argerich made her US debut the same year. For the next 10 years she played up to 150 concerts a year, but by 1980 she scaled down the number of concerts and her solo performances became quite unpredictable: it was never clear whether Argerich would play a concert or cancel it. She was (and still is) much more consistent when playing chamber music, often partnering with the pianists Nelson Freire and Stephen Bishop-Kovacevich, the violinist Gidon Kremer and cellist Mischa Maisky; she often performs with the conductor Charles Dutoit – all either good friends of hers or, like Kovacevich and Dutoit, former husbands. Here’s Martha Argerich playing Bach’s English Suite No. 2 in A minor, BWV 807. Bach is not the composer we usually associate with her repertoire but, as you can hear yourself, Martha’s playing is superb.Permalink

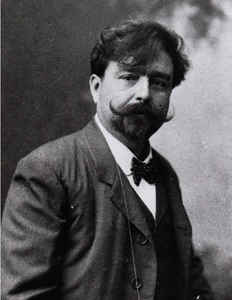

This Week in Classical Music: May 25, 2020. Albéniz and Korngold. In four days we’ll celebrate the 160th anniversary of a wonderful Spanish composer Isaac Albéniz: he was born near Gerona on May 29th of 1860 (the family moved to Barcelona when Isaac was one year old). A child prodigy, he played paino publicly at the age of three and was refused entry into the Paris Conservatory only because he was just seven when he took the exams (everybody said that the jury was impressed with his talent). As a teenager he performed around Europe and even gave concerts in the Spanish-speaking American countries like Puerto Rico and Cuba. At the age of 15, Albéniz settled down, concentrating more on his studies. He was admitted to the Brussels conservatory and performed little for the next five years. By 1885, at 25, he moved to Madrid and established himself as a major figure in the music circles. He took on conducting and was composing (in concerts, he often performed his own piano music).

Gerona on May 29th of 1860 (the family moved to Barcelona when Isaac was one year old). A child prodigy, he played paino publicly at the age of three and was refused entry into the Paris Conservatory only because he was just seven when he took the exams (everybody said that the jury was impressed with his talent). As a teenager he performed around Europe and even gave concerts in the Spanish-speaking American countries like Puerto Rico and Cuba. At the age of 15, Albéniz settled down, concentrating more on his studies. He was admitted to the Brussels conservatory and performed little for the next five years. By 1885, at 25, he moved to Madrid and established himself as a major figure in the music circles. He took on conducting and was composing (in concerts, he often performed his own piano music).

In 1890, after securing a suitable contract, Albéniz moved to London, where he wrote his first opera, which was published and performed that same year. He was also actively writing zarzuelas, typically Spanish dramatic compositions, a combination of opera and theater. Zarzuelas were usually rather short, like operettas they combined singing with spoken scenes and sometimes included popular songs and dance numbers. During his life, Albéniz wrote four zarzuelas and six operas, some of which he started as zarzuelas. In 1895 Albéniz moved to Paris and soon after became part of the French musical establishment; he was good friends with Vincent d'Indy, Ernest Chausson, Paul Dukas and Gabriel Fauré.

From around 1900 Albéniz began suffering from kidney disease, he felt better in warner climates and left Paris for Spain. He was also spending time in Nice. During this period, he was composing operas, unti, in 1905, he embarked on writing a series of “musical impressions” for the piano he called Iberia. It was to be his last masterpiece. Iberia was completed in 1908, and just one year later Albéniz died of acute kidney disease; he was 48 years old.

Erich Wolfgang Korngold was also born this week, on May 29th of 1897. You can read more about him (and Albéniz) in one of our older entries here. Korngold was also a child prodigy, and a remarkable one: he started composing at a very young age, and, when he was nine, played a cantata, called Gold, to Gustav Mahler, who pronounced him a genius. At 11 he composed a ballet, Der Schneemann, which was performed at the Vienna Court Opera. His second piano sonata was championed by none other than Artur Schnabel. In 1914, at the age of 17, he completed two operas, Der Ring des Polykrates and Violanta. His opera Die tote Stadt premiered in 1920 and made him world-famous. His other opera, Das Wunder der Heliane (The Miracle of Heliane), premiered in 1927, was considered a flop, but at least one aria from it, Ich ging zu ihm (“I went to him”) was made famous by the soprano Renee Fleming. Here she is, singing the aria at the 2007 Prom in Albert Hall. The BBC Philharmonic Orchestra is conducted by Gianandrea Noseda.Permalink

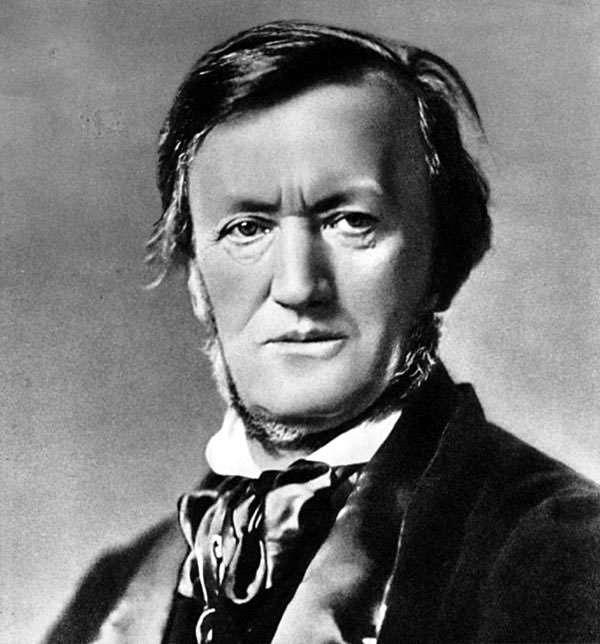

This Week in Classical Music: May 18, 2020. Wagner. Richard Wagner was born on May 22nd of 1813. One of the most important achievements of his life was the establishment of the Bayreuth Festival (or Bayreuther Festspiele in German) in 1876. One of the most important and prestigious music festivals in the world, it ran with few interruptions since then but this year it was cancelled because of the coronavirus. This is a strange time we’re living in.

the Bayreuth Festival (or Bayreuther Festspiele in German) in 1876. One of the most important and prestigious music festivals in the world, it ran with few interruptions since then but this year it was cancelled because of the coronavirus. This is a strange time we’re living in.

Wagner was thinking of establishing a festival to promote his operas since the breakup with his patron of many years, King Ludwig II of Bavaria in 1865, when he had to leave Munich under a cloud. On the advice of his friend, the conductor Hans Richter, Wagner selected Bayreuth, a Bavarian town near Nuremberg as the place for the festival, partly on the assumption that the existing opera house would be an adequate venue. The theater, while beautiful, proved to be insufficient for the enormous productions envisioned by the composer, but the city was supportive and with its help Wagner embarked on the construction of a new theater. The money soon dried up and Wagner went fundraising around Germany. Twice he talked to the Chancellor Bismarck, to no avail. Eventually Wagner was forced to appeal to his former patron, King Ludwig, who, reluctantly, lent Wagner the money. The theater’s cornerstone was laid on May 22nd, 1872, (Wagner's birthday) and the theater was opened to the public in August of 1876; Das Rheingold was performed three nights in a row. The German Kaiser Wilhelm and King Ludwig both attended (on separate nights, as Ludwig was against Bavaria losing its independence within the newly-formed Germany), and so did many luminaries, including Wagner’s father-in-law Franz Liszt, Anton Bruckner, Edvard Grieg, and Tchaikovsky. The opening, while musically highly successful, was a disaster financially, and the second season took place only six years later, in 1882. It was dedicated exclusively to Parsifal, which was written specifically for the Festspielhaus. Wagner himself conducted the final scene of the last performance. He died less than a year later. Since then it’s been the Wagners who have been running the festival. First, Richard’s widow Cosima List Wagner took over, then Siegfried Wagner, Richard and Cosima’s son. Siegfried died in 1930 and his wife, Winifred Wagner became the director. This infamous friend and admirer of Adolph Hitler ran the Bayreuth till 1945. After the war, the festival resumed in 1951 with Wagner’s grandsons Wieland and Wolfgang Wagner at the helm. After Wieland’s death in 1966 his brother continued on his own, till 2008. Wolfgan’s daughters Eva and Katharina Wagner ran the festival together till 2015, and since then Katharina has been running it alone. Let us hope that the hiatus is short and that the 2021 festival will take place as scheduled.

The great Wagnerian soprano Birgit Nilsson was also born this week, on May 17th of 1918.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: May 11, 2020. Bits and pieces. Claudio Monteverdi, a great Italian composer, was born this week, on May 15th of 1567, but we’ve written about him so many times (here, here, here and more) that we will skip the event this time around. Otherwise, several very good but hardly great Frenchmen: Massenet, Fauré and Satie (born on May 12th of 1842, on the same day of 1845 and on May 17th of 1866 respectively), a very nice but underappreciated Czech composer Jan Václav Voříšek was born on May 11th of 1791; he died of tuberculosis at the age of 34, who knows how far his talent would’ve carried him had he lived longer. Then, to quote one of our earlier entries,, “Anatol Liadov, a minor but pleasant composer of short piano pieces. Were it not for his laziness and lack for self-assurance, he might’ve developed into a major talent (Liadov was born on May 12th of 1855).” And we cannot seriously celebrate the birthday of Maria Theresia von Paradis any longer (she was born on May 15th of 1759) because, as it turns out, the only piece of interest, Sicilienne, was written not by her but by the violinist Samuel Dushkin, who arranged the music from the second movement of Carl Maria von Weber’s Violin Sonata op. 10 no. 1 and presented it as her piece.

times (here, here, here and more) that we will skip the event this time around. Otherwise, several very good but hardly great Frenchmen: Massenet, Fauré and Satie (born on May 12th of 1842, on the same day of 1845 and on May 17th of 1866 respectively), a very nice but underappreciated Czech composer Jan Václav Voříšek was born on May 11th of 1791; he died of tuberculosis at the age of 34, who knows how far his talent would’ve carried him had he lived longer. Then, to quote one of our earlier entries,, “Anatol Liadov, a minor but pleasant composer of short piano pieces. Were it not for his laziness and lack for self-assurance, he might’ve developed into a major talent (Liadov was born on May 12th of 1855).” And we cannot seriously celebrate the birthday of Maria Theresia von Paradis any longer (she was born on May 15th of 1759) because, as it turns out, the only piece of interest, Sicilienne, was written not by her but by the violinist Samuel Dushkin, who arranged the music from the second movement of Carl Maria von Weber’s Violin Sonata op. 10 no. 1 and presented it as her piece.

Two prominent conductors were born this week, Carlo Maria Giulini and Otto Klemperer. We wrote about Klemperer not that long ago (here), but never about Giulini. Carlo Maria Giulini was born on May 9th of 1914 in Barletta, in southern Italy. He studied the viola and conducting at the Academy of Santa Cecilia and then played in the Academy’s orchestra. In 1944 he became the orchestra’s conductor, then was hired to lead the orchestra of the Italian Radio. In 1964 he was appointed the principal conductor at La Scala. There he worked closely with Maria Callas and with the directors Luchino Visconti and Franco Zeffirelli. Later he worked with Visconti at Covent Garden, London, where he conducted several operas. During the late 1950s and 1960s Giulini was closely associated with the Philharmonia Orchestra, London. In 1969 he became Principal guest conductor at the Chicago Symphony, and in 1978 – the Chief conductor at the Los Angeles Philharmonic. His performances of Verdi’s Requiem were famous, and so were his staging of Mozart and Verdi operas in Los Angeles and Milan. Giulini died in Brescia (recently an epicenter of one of the major coronavirus outbreaks in Italy) on June 14th of 2005.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: May 4, 2020. Tchaikovsky and more. This is one of these weeks when we don’t even know where to start: half a dozen composes, two pianists and three conductors all born within the next 7 days. We’ll have to start with Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: May 7th marks the 180th anniversary of his birthday. If you sense some reluctance on our part, you may be right. Don’t get us wrong: we consider Tchaikovsky a major talent, the most important Russian composer of the second half of the 19th century who influenced many, among them Igor Stravinsky. His Piano concerto in B-flat minor (no. 1), the Violin concerto; his last three symphonies, from no. 4 to no. 6; operas like “Eugene Onegin” and “The Queen of Spades” and some other pieces are of the highest quality. And he cuts a sympathetic figure: a homosexual in a conservative Russian society who attempted to marry to please his family – with disastrous results; a wanderer, who spend many years in Europe; a social recluse, who had an unusual relationship with his major benefactor, Nadezhda von Meck, whom he never met; his many personal traumas; his death of cholera at the age of only 53 which many think was a suicide – all this endears us to Tchaikovsky. So what of our hesitancy? It has nothing to do with a lot of mediocre music Tchaikovsky had written (like his 2nd and 3rd Piano concertos, or many operas, or much of the ballet music) – not a single composer, Mozart including, had written music on the highest level all the time - we value composers for their best piece, not judge them on their worst. No, the problem – and if there is one, it’s probably with our perception, not with Tchaikovsky – is with his unusual position vis-à-vis the development of European music. As much as his music is integral to it, he stands apart. Tchaikovsky died in 1893 and was writing till the very end; by then the whole symphonic tradition, originating with Wagner and then brought up by Bruckner and Mahler had been developed (Bruckner’s Symphony no. 4 was premiered in 1881; Mahler’s Symphony no. 1 – in 1889). A very different but highly innovative composer, Claude Debussy was already active for some years (his Suite Bergamasque was composed in 1890). Tchaikovsky seems to be out of step; despite his influence on Rachmaninov and many Russian and Soviet symphonists, it feels like the path he broke doesn’t lead anywhere. Whether it’s true or not, in the end it probably doesn’t matter. Here, to celebrate Tchaikovsky’s 180th, is a brilliant 2nd movement from Tchaikovsky’s last, Sixth Symphony. It was written in a 5/4 tempo: try to “conduct” it yourself while following a recording – it’s really difficult. In this particular case, the real conductor is Sir Georg Solti, leading the very nimble Chicago Symphony orchestra.

conductors all born within the next 7 days. We’ll have to start with Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: May 7th marks the 180th anniversary of his birthday. If you sense some reluctance on our part, you may be right. Don’t get us wrong: we consider Tchaikovsky a major talent, the most important Russian composer of the second half of the 19th century who influenced many, among them Igor Stravinsky. His Piano concerto in B-flat minor (no. 1), the Violin concerto; his last three symphonies, from no. 4 to no. 6; operas like “Eugene Onegin” and “The Queen of Spades” and some other pieces are of the highest quality. And he cuts a sympathetic figure: a homosexual in a conservative Russian society who attempted to marry to please his family – with disastrous results; a wanderer, who spend many years in Europe; a social recluse, who had an unusual relationship with his major benefactor, Nadezhda von Meck, whom he never met; his many personal traumas; his death of cholera at the age of only 53 which many think was a suicide – all this endears us to Tchaikovsky. So what of our hesitancy? It has nothing to do with a lot of mediocre music Tchaikovsky had written (like his 2nd and 3rd Piano concertos, or many operas, or much of the ballet music) – not a single composer, Mozart including, had written music on the highest level all the time - we value composers for their best piece, not judge them on their worst. No, the problem – and if there is one, it’s probably with our perception, not with Tchaikovsky – is with his unusual position vis-à-vis the development of European music. As much as his music is integral to it, he stands apart. Tchaikovsky died in 1893 and was writing till the very end; by then the whole symphonic tradition, originating with Wagner and then brought up by Bruckner and Mahler had been developed (Bruckner’s Symphony no. 4 was premiered in 1881; Mahler’s Symphony no. 1 – in 1889). A very different but highly innovative composer, Claude Debussy was already active for some years (his Suite Bergamasque was composed in 1890). Tchaikovsky seems to be out of step; despite his influence on Rachmaninov and many Russian and Soviet symphonists, it feels like the path he broke doesn’t lead anywhere. Whether it’s true or not, in the end it probably doesn’t matter. Here, to celebrate Tchaikovsky’s 180th, is a brilliant 2nd movement from Tchaikovsky’s last, Sixth Symphony. It was written in a 5/4 tempo: try to “conduct” it yourself while following a recording – it’s really difficult. In this particular case, the real conductor is Sir Georg Solti, leading the very nimble Chicago Symphony orchestra.

Where there is Tchaikovsky, there is Johannes Brahms. They were born on the same day, Brahms in 1833, sever years before Tchaikovsky. And other composers that were also born this week are, in a historical order: Giovanni Paisiello, an Italian and the most popular opera composer of the late 18th century (May 9, 1740); Carl Stamitz (May 8, 1745), the German composer of the Mannheim School fame; Stanislaw Moniuszko, the creator of the Polish national opera (May 5, 1819); Louis Moreau Gottschalk, an American of half-Jewish, half French-Creole descent (May 8, 1829), very popular in his days; and, finally, Milton Babbitt, one of the most interesting American modernist composers of the last century. As for the pianists and conductors, those will have to wait till next year.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: April 27, 2020. Scarlatti père. Alessandro Scarlatti, one of the most interesting opera composers of the Italian Baroque, was born on May 2nd of 1660 in.jpg) Palermo. He’s considered the founder of the Neapolitan school of opera, the school that gave the world such composers as Nicola Porpora, Leonardo Vinci, Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, Niccolò Piccinni, Giovanni Paisiello and Domenico Cimarosa. Scarlatti’s family moved to Rome when he was 10. He married a Roman girl at 18 and then managed to establish connections at the very top of the Roman society: he stayed at the palace of the famous sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini; Cardinal Benedetto Pamphili, a patron of arts and a member of Accademia dell'Arcadia, provided a libretto to several of Scarlatti’s operas and introduced him to the circle of Queen Christina of Sweden (Scarlatti himself would eventually join the prestigious Academy, founded under the patronage of Queen Christina).

Palermo. He’s considered the founder of the Neapolitan school of opera, the school that gave the world such composers as Nicola Porpora, Leonardo Vinci, Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, Niccolò Piccinni, Giovanni Paisiello and Domenico Cimarosa. Scarlatti’s family moved to Rome when he was 10. He married a Roman girl at 18 and then managed to establish connections at the very top of the Roman society: he stayed at the palace of the famous sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini; Cardinal Benedetto Pamphili, a patron of arts and a member of Accademia dell'Arcadia, provided a libretto to several of Scarlatti’s operas and introduced him to the circle of Queen Christina of Sweden (Scarlatti himself would eventually join the prestigious Academy, founded under the patronage of Queen Christina).

The cultural and musical life of Rome at the end of the 17th century was flourishing. This was somewhat of a miracle, as not that long prior, in 1527, Rome was devastated during the catastrophe of the Sack of Rome, when the mutinous troops of Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, entered and pillaged the city, killing and raping its inhabitants and plundering everything of value. The troops stayed in the city and continued the plunder for almost eight months, till the food ran out. When they left, the population of Rome was 10,000 – a year earlier it had been 55,000. The Sack of Rome marked the end of the Italian Renaissance, as most artists left Rome and never returned (though the event gave birth to the period called Mannerism). But despite everything, the devastated Rome was rebuilt, Michelangelo completed the design of the great cupola of St. Peter’s Basilica and Carlo Maderna finished its monumental façade in 1612. Baroque changed the face of the city, and Bernini, the sculptor of genius, embellished it as never before. By the end of the 16th century the population of Rome grew to 100,000 and by the time of Scarlatti it was even larger. The popes and the cardinals, despite all the corruption and nepotism, proved to be great patrons of arts; Cardinal Pamphili was one of the most important. His birthday was just two days ago – he was born on April 25th of 1653. We’ve written about Queen Christina and Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni, two great patrons of art – we should write about Benedetto Pamphili as well, he very much deserves it.

Scarlatti’s opera Gli equivoci nel sembiante (“Equivocal Appearances”) was so successful that Queen Christina appointed him her maestro di cappella; at the time Scarlatti was just eighteen. In the following six years, six of his operas were staged in Rome, quite a success for a young composer. But opera came under pressure from the church and the pope: religious authorities considered this art profane, and most operas were staged in private theaters. In 1684 Scarlatti received an offer from the Viceroy of Naples to become his maestro di cappella and left Rome. Here’s the aria Onde, ferro, fiamme e morte (Waves, iron, flames and death) from Gli equivoci nel sembiante. Renata Fusco is the soprano.Permalink