Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

This Week in Classical Music: July 13, 2020. On Mahler and the Music Scene. Last week we celebrated Gustav Mahler’s 160th anniversary. WFMT, the premier classical music station based in Chicago, also celebrated the event: they played 10 minutes of the Finale of the Symphony no. 4, when Carl Grapentine, their former morning host who now presents “Carl’s Almanac,” short musical introductions, spoke about Mahler for a couple of minutes. Then, at the end of the day, WFMT played "Adagietto," the fourth movement of Symphony no. 5, which, after so much use and misuse turned trite and reminds one more of Luchino Visconti’s film “Death in Venice” rather than Mahler’s symphony. And this is how the same WFMT celebrated Mahler’s 150th anniversary ten years ago: they played all of his symphonies plus Das Lied von der Erde and several song cycles. They played them without interruption, from beginning to end. This was a heroic undertaking: WFMT is a commercial station and they depend on advertising. There is little opportunity to advertise when you run an hour and 40 minutes of Mahler’s Symphony no. 3 straight from the beginning to the end. And still they did it and it was wonderful. Times have changed… But what actually did change? Did music lovers decide that they prefer lighter pieces, and stations like WFMT got the message and adjusted their programming accordingly? Or have listeners found other outlets, like Pandora, Spotify or other Internet streaming services? That would put pressure on commercial radio station, which would try to boost sagging advertising revenues by playing shorter (and often lighter) pieces to squeeze in more ads. We don’t know for sure, maybe services like Nielsen could tell us. We suspect that people still like Mahler. If you go to YouTube, yet another competitor of radio stations, and search for Mahler’s Symphony no. 3, you’ll find that the video recording made in 1973 of Leonard Bernstein conducting the Vienna Philharmonic with Christa Ludwig was watched more than 1.6 million times. It’s likely that not everybody listened to the entire symphony to the end (even though the finale is sublime), but 1.6 million is an amazing number. And that’s just one recording. Cladio Abbado with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra garnered 240,000 views. Semyon Bychkov with WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne got another 140,000 views. There are many more recordings of just this one very complex symphony. The easier Mahlerian music, such as his Symphony no. 1, got 2.6 million views (that again from Bernstein and the Vienna Philharmonic). The record holder is probably Gergiev with the so-called Orchestra for Piece, founded in 1995 by Sir Georg Solti: their recording of Mahler’s Symphony no. 5 was watched by four million viewers. So it seems there is no shortage of classical music lovers and outlets to satisfy them. The competition is fearsome and the pressure on classical music radio stations is fierce. We hope they survive, but not by turning away from Mahler.Permalink

4, when Carl Grapentine, their former morning host who now presents “Carl’s Almanac,” short musical introductions, spoke about Mahler for a couple of minutes. Then, at the end of the day, WFMT played "Adagietto," the fourth movement of Symphony no. 5, which, after so much use and misuse turned trite and reminds one more of Luchino Visconti’s film “Death in Venice” rather than Mahler’s symphony. And this is how the same WFMT celebrated Mahler’s 150th anniversary ten years ago: they played all of his symphonies plus Das Lied von der Erde and several song cycles. They played them without interruption, from beginning to end. This was a heroic undertaking: WFMT is a commercial station and they depend on advertising. There is little opportunity to advertise when you run an hour and 40 minutes of Mahler’s Symphony no. 3 straight from the beginning to the end. And still they did it and it was wonderful. Times have changed… But what actually did change? Did music lovers decide that they prefer lighter pieces, and stations like WFMT got the message and adjusted their programming accordingly? Or have listeners found other outlets, like Pandora, Spotify or other Internet streaming services? That would put pressure on commercial radio station, which would try to boost sagging advertising revenues by playing shorter (and often lighter) pieces to squeeze in more ads. We don’t know for sure, maybe services like Nielsen could tell us. We suspect that people still like Mahler. If you go to YouTube, yet another competitor of radio stations, and search for Mahler’s Symphony no. 3, you’ll find that the video recording made in 1973 of Leonard Bernstein conducting the Vienna Philharmonic with Christa Ludwig was watched more than 1.6 million times. It’s likely that not everybody listened to the entire symphony to the end (even though the finale is sublime), but 1.6 million is an amazing number. And that’s just one recording. Cladio Abbado with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra garnered 240,000 views. Semyon Bychkov with WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne got another 140,000 views. There are many more recordings of just this one very complex symphony. The easier Mahlerian music, such as his Symphony no. 1, got 2.6 million views (that again from Bernstein and the Vienna Philharmonic). The record holder is probably Gergiev with the so-called Orchestra for Piece, founded in 1995 by Sir Georg Solti: their recording of Mahler’s Symphony no. 5 was watched by four million viewers. So it seems there is no shortage of classical music lovers and outlets to satisfy them. The competition is fearsome and the pressure on classical music radio stations is fierce. We hope they survive, but not by turning away from Mahler.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: July 6, 2020. Mahler at 160. Gustav Mahler, one of the greatest composers in the history of music (Grove Dictionary is more circumspect, calling him “one of the most important figures of European art music in the 20th century,” but we think he was much more than that) was born on July 7th of 1860 in a small town of Kaliště in Moravia (then Kalischt, Austria-Hungary). We’ve been tracing Mahler’s life by his symphonies, the last one, two years ago, being his Symphony no. 6, written in 1903 – 1904. The Seventh followed soon after: Mahler started working on the symphony in 1904 and completed it a year later; he conducted the premiere in Prague in 1908, the work wasn’t well received. By 1904 Mahler’s routine was well established: he would spend music seasons conducting and producing operas at the Hofoper in Vienna and conducting subscription symphonic concerts, and then compose during several summer weeks at his “composing hut” at Maiernigg on lake Wörthersee, near the resort town of Maria Wörth in Carinthia. The summer of 1904 Mahler spent most of the time struggling to complete the Sixth symphony; as for the next one, he only sketched out two Nachtmusik movements (they would become movements two and four once the symphony was completed). The following year, 1905, he was again in trouble. We quote here Mahler’s letter to his wife Alma from an article by the noted Mahler scholar Henry-Louis de La Grange: “I plagued myself for two weeks until I sank into gloom, as you well remember, then I tore off to the Dolomites. There I was led the same dance, and at last gave it up and returned home, convinced that the whole summer was lost. You were not at Krumpendorf [a town on the opposite side of Wörthersee from Maiernigg]to meet me, because I had not let you know the time of my arrival. I got into the boat to be rowed across. At the first stroke of the oars the theme (or rather the rhythm and character) of the introduction to the first movement came into my head—and in four weeks the first, third and fifth movements were done.” This is quite remarkable, as the first movement lasts about 21 minutes, the third – about 10 and the fifth – about 18: Mahler wrote about 50 minutes of very complex symphonic music in just four weeks.

“one of the most important figures of European art music in the 20th century,” but we think he was much more than that) was born on July 7th of 1860 in a small town of Kaliště in Moravia (then Kalischt, Austria-Hungary). We’ve been tracing Mahler’s life by his symphonies, the last one, two years ago, being his Symphony no. 6, written in 1903 – 1904. The Seventh followed soon after: Mahler started working on the symphony in 1904 and completed it a year later; he conducted the premiere in Prague in 1908, the work wasn’t well received. By 1904 Mahler’s routine was well established: he would spend music seasons conducting and producing operas at the Hofoper in Vienna and conducting subscription symphonic concerts, and then compose during several summer weeks at his “composing hut” at Maiernigg on lake Wörthersee, near the resort town of Maria Wörth in Carinthia. The summer of 1904 Mahler spent most of the time struggling to complete the Sixth symphony; as for the next one, he only sketched out two Nachtmusik movements (they would become movements two and four once the symphony was completed). The following year, 1905, he was again in trouble. We quote here Mahler’s letter to his wife Alma from an article by the noted Mahler scholar Henry-Louis de La Grange: “I plagued myself for two weeks until I sank into gloom, as you well remember, then I tore off to the Dolomites. There I was led the same dance, and at last gave it up and returned home, convinced that the whole summer was lost. You were not at Krumpendorf [a town on the opposite side of Wörthersee from Maiernigg]to meet me, because I had not let you know the time of my arrival. I got into the boat to be rowed across. At the first stroke of the oars the theme (or rather the rhythm and character) of the introduction to the first movement came into my head—and in four weeks the first, third and fifth movements were done.” This is quite remarkable, as the first movement lasts about 21 minutes, the third – about 10 and the fifth – about 18: Mahler wrote about 50 minutes of very complex symphonic music in just four weeks.

The years 1904 – 1905 were good to Mahler. He was acknowledged as a great opera conductor, and his symphonic programs with the Philharmonic were popular. Some of his compositions even had critical and popular success (Symphony no. 7 would not go on to be one of them). He lived very comfortably, was happily married, and his second daughter, Anna, was born in 1904. He had many friends and admirers among musicians and developed a special relationship with the Concertgebouw Orchestra and its conductor Willem Mengelberg. Just three years later Mahler would have to leave Hofoper, hounded by antisemitic music critics; in 1907 his first daughter, Maria, would die of scarlet fever and his marriage to Alma would be on the rocks.

Symphony no. 7 consists of five movements, which you could listen to separately Langsam, Allegro, Nachtmusik I, Scherzo, Nachtmusik II, and Rondo-Finale, or to the whole symphony here. Leonard Bernstein conducts the New York Philharmonic in this 1985 recording.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: June 29, 2020. Henze, Gluck and Janáček. The calendar divides composers into serendipitous groups, and this week we have three that are as musically different as they can get. Christoph Willibald Gluck was a famous opera composer, who created a new style by merging the Italian and French traditions; for six years he was feted in Paris where some of his best operas, Orphée et Euridice, Iphigénie en Aulide, Alceste and Iphigénie en Tauride saw their premiers. Then, after one failure (with Echo et NarcisseI), he fell out of favor, left Paris and lived the rest of his live in Vienna suffering from melancholy. Gluck was born on July 2nd of 1714, you can read more about him here.

different as they can get. Christoph Willibald Gluck was a famous opera composer, who created a new style by merging the Italian and French traditions; for six years he was feted in Paris where some of his best operas, Orphée et Euridice, Iphigénie en Aulide, Alceste and Iphigénie en Tauride saw their premiers. Then, after one failure (with Echo et NarcisseI), he fell out of favor, left Paris and lived the rest of his live in Vienna suffering from melancholy. Gluck was born on July 2nd of 1714, you can read more about him here.

While Gluck was born in what is now Germany, in his youth he spent many years in Prague, capital of the Czech Republic; Leoš Janáček, also born this week (July 3rd of 1854), is one of the most interesting Czech composers. He, like Gluck is also remembered mostly for his operas: Jenůfa (1904), Káťa Kabanová, based on a play Storm by the Russian playwright Alexander Ostrovsky (the opera was composed in 1921) and The Cunning Little Vixen, completed in 1923. Unlike Gluck, Janáček also wrote a number of orchestral, chamber and piano pieces (On the Overgrown Path is probably the most popular of the latter). Here’s his Sinfonietta, from 1926. The Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra is conducted by Antoni Wit.

Hans Werner Henze, a German composer, was born on July 1st of 1926. We usually don’t care much about political views of composers, but Henze lived very recently (he died in 2012) and his political views affected much of what he wrote. He was a Marxist, a member of the Italian Communist Party (Henze moved to Italy when he was 27 and lived there for many years), he composed works honoring Che Guevara and Ho Chi Minh, he supported the Cuban revolution (and spent time in Cuba) and wrote songs based on communist verses. At the same time, Henze was creating some of the most original and interesting music, incorporating different styles, from jazz to twelve-tone. Henze was very prolific: as Gluck and Janáček, Henze wrote several operas, he also wrote ten symphonies, ballet scores, choral pieces and chamber music. Here’s a more accessible, lyrical piece by Henze, his Adagio Adagio. It’s performed by Edna Michell (violin), Michal Kanka (cello) and Igor Ardašev (piano).

Also, two wonderful Hungarian musicians were born this week: the pianist Annie Fischer, on July 5th of 1914 and the cellist János Starker, exactly 10 years later. Both were of Jewish descent; Fischer fled to Sweden in 1940 and returned to Hungary after the war, Starker survived the war in Hungary (his brothers perished in the Holocaust), left the country in 1946 and moved to the US in 1948. He was the principal cello at the Dallas, Metropolitan and Chicago symphonies and widely toured the world as a solo performer. He was considered one of the greatest cellists of the second half of the 20th century.

PermalinkThis Week in Classical Music: June 22, 2020. Orlando di Lasso. No, the great Franco-Flemish composer of the Renaissance was not born this week. We are not even sure when he was born, whether in 1530 or 1532. We do know, though, that he was one of the greatest and most prolific composers of his time. Orlando, often spelled as Orlande de Lassus, was born in the town of Mons in the County of Hainaut in what is now Belgium; at that time Hainaut and the rest of the Low Countries were part of the empire of Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor. As a boy, Orlando moved to Italy with Ferrante Gonzaga, a condottiero who was then serving Charles V (Ferrante belonged to a minor branch of Gonzagas, the dukes of Mantua). Orlando’s first stop in Italy was Mantua but several months later Ferrante left the city for Sicily, with Orlando in tow. After serving at several Italian courts, Orlando moved to Rome, where, in 1553, he became maestro di cappella at San Giovanni in Laterano, a position that eventually would be assumed by Palestrina. We know that during that time Orlando traveled to many cities in Europe, possibly visiting England. In 1555 he went to Antwerp, where he met many musicians and made friends with Tielman Susato, a composer and major music publisher. That year Susato published Orlando’s music, his “opus 1.”

born, whether in 1530 or 1532. We do know, though, that he was one of the greatest and most prolific composers of his time. Orlando, often spelled as Orlande de Lassus, was born in the town of Mons in the County of Hainaut in what is now Belgium; at that time Hainaut and the rest of the Low Countries were part of the empire of Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor. As a boy, Orlando moved to Italy with Ferrante Gonzaga, a condottiero who was then serving Charles V (Ferrante belonged to a minor branch of Gonzagas, the dukes of Mantua). Orlando’s first stop in Italy was Mantua but several months later Ferrante left the city for Sicily, with Orlando in tow. After serving at several Italian courts, Orlando moved to Rome, where, in 1553, he became maestro di cappella at San Giovanni in Laterano, a position that eventually would be assumed by Palestrina. We know that during that time Orlando traveled to many cities in Europe, possibly visiting England. In 1555 he went to Antwerp, where he met many musicians and made friends with Tielman Susato, a composer and major music publisher. That year Susato published Orlando’s music, his “opus 1.”

In 1556 Orlando received an invitation from Albrecht V, Duke of Bavaria to join his court; Orland accepted and moved to Munich. His initial position was that of a singer (tenor) in the Duke’s chapel (choir), which was being refashioned in the Flemish style. Orlando, who by then was well known as a composer, continued to write and publish music; soon he was made maestro di cappella of the Bavarian court. He stayed in that position for the rest of his life. Orlando’s duties included composing music for morning masses and numerous Magnificats for the Vespers in the evening. He also wrote a copious number of motets. In addition to church music, Orlando wrote many secular pieces composed for different court events: Tafelnusik for the feasts and banquets, and music for other occasions, for example, hunting parties. On top of that he was supervising music education of the choirboys – all that reminds us of the enormous workload Johann Sebastian Bach had as a Thomaskantor in Leipzig some century and a half later.

Orlando’s position at the court was exceptional: he was a friend to the duke and especially to his heir, the future Wilhelm V. He traveled extensively, hiring musicians in the Flanders, attending coronations in Prague and Frankfurt. When he visited Ferrara and Venice (in 1567) he told his hosts that good Italian music could be had even in a far-off Germany. He visited a French court on the invitation of King Charles IX. In 1570 Orlando was made a noble by Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor.

Orlando died in Munich on June 14th of 1594, the same year as Palestrina. Enormously productive, he wrote more than 60 masses and hundreds of motets. Here’s one of them, In Monte Oliveti, performed by the Hilliard Ensemble directed by Paul Hillier.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: June 15, 2020. Musical dynasties, Stravinsky. Several very interesting composers were born this week, two of them belonging to dynasties: Johann Stamitz was the head of one, while Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach was one of several sons of Johann Sebastian who became prominent composers. Johann Stamitz was born on June 18th of 1717 in Bohemia, then ruled by the Habsburgs and to a large extent dominated by the German language and Austrian-German culture. Stamitz was a violin virtuoso; sometime around 1741 he was hired by the Mannheim Court to play in the famous orchestra. Stamitz’s career advanced quickly: he was soon appointed Konzertmeister, then Director of Court music and the orchestra’s chief conductor. Stamitz developed the orchestra into the “most renowned ensemble of the time, famous for its precision and its ability to render novel dynamic effects,” to quote the musicologist and historian Eugene Wolf. Johann’s sons Carl and Anton were among the best composers of the Mannheim school, of which their father was the founder.

of Johann Sebastian who became prominent composers. Johann Stamitz was born on June 18th of 1717 in Bohemia, then ruled by the Habsburgs and to a large extent dominated by the German language and Austrian-German culture. Stamitz was a violin virtuoso; sometime around 1741 he was hired by the Mannheim Court to play in the famous orchestra. Stamitz’s career advanced quickly: he was soon appointed Konzertmeister, then Director of Court music and the orchestra’s chief conductor. Stamitz developed the orchestra into the “most renowned ensemble of the time, famous for its precision and its ability to render novel dynamic effects,” to quote the musicologist and historian Eugene Wolf. Johann’s sons Carl and Anton were among the best composers of the Mannheim school, of which their father was the founder.

Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach was Johan Sebastian’s fifth son. He was born on June 21stof 1732 in Leipzig, where his father was serving as Thomaskantor teaching at the Thomasschuleand composing for and playing at the Thomaskirche. J.C.F. is not as well known as his half-brothers Whilhelm Friedeman and Carl Philipp Emanuel, or his brother Johann Christian. Part of the reason may be that many of his scores were lost during the WWII bombing of Berlin; they were stored at the National Institute of the German Music Research, and most of its collection of scores and musical instruments were lost. Here’s his lively Piano Concerto in E Major, perfomed by Cyprien Katsaris, piano, with the Orchestre de Chambre du Festival d`Echternach, Yoon K. Lee conducting.

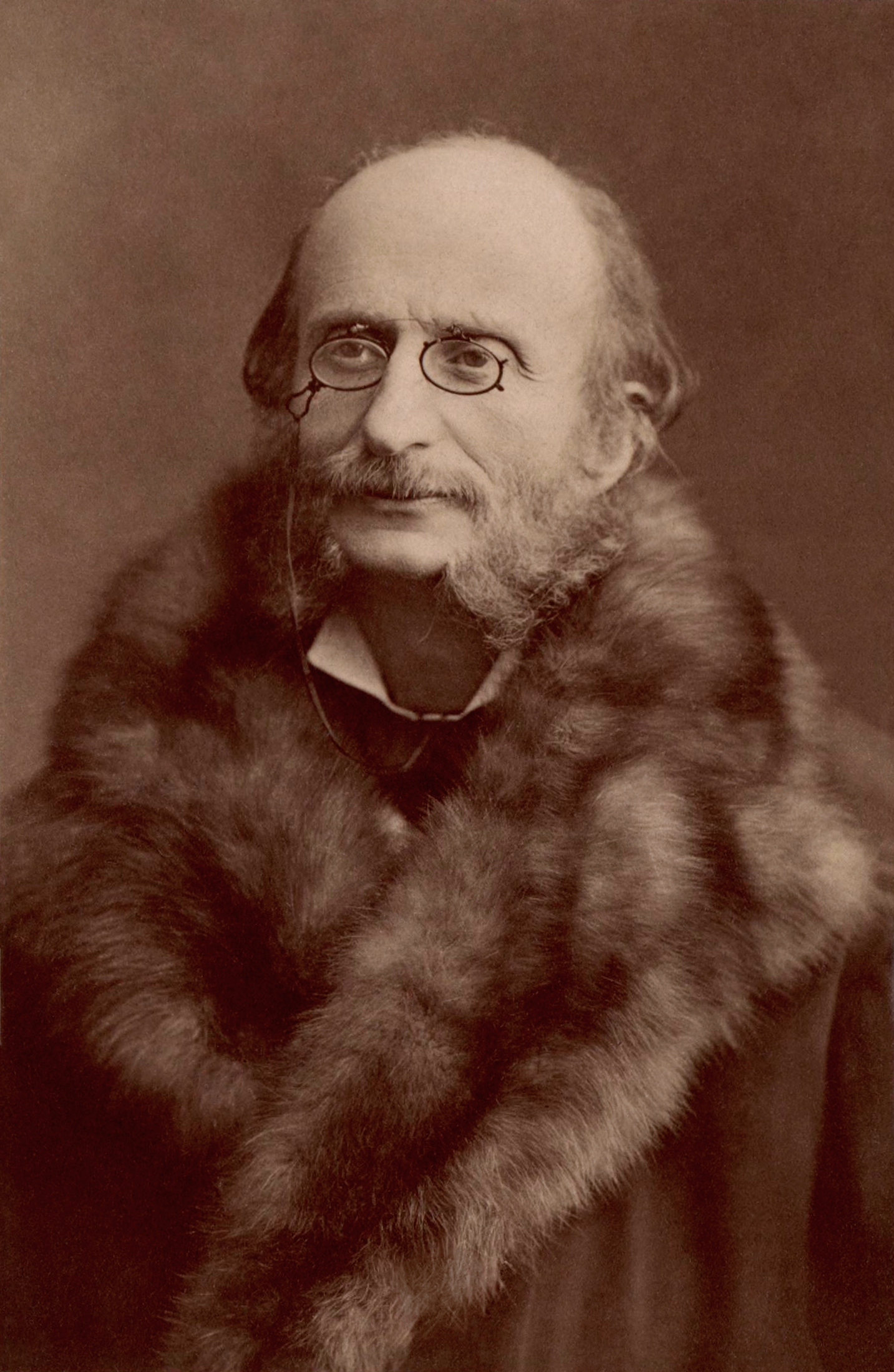

We celebrated Charles Gounod’s 200th anniversary in 2018, you can check out our entry here. Edvard Grieg was born on this day in 1843. And then there was Jacques Offenbach, a German-Jewish composer from Cologne who practically invented the genre of operetta and became the most popular French composer of his time. Offenbach wrote 100 opera-buffe (operettas) and one unfinished opera, The Tales of Hoffmann, a staple of the opera repertoire. Here’s the overture to La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein. It’s not serious music, and was composed to be light, but the orchestration is quote brilliant and the whole piece is a lot of fun. In this recording the Philharmonia Orchestra is conducted by Sir Neville Marriner. (By the way, the librettists of La Grande-Duchesse were Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy – Halévy was the nephew of another French Jewish composer Fromental Halévy; Meilhac and Halévy also co-wrote the libretto for the famous Carmen.)

Offenbach, a German-Jewish composer from Cologne who practically invented the genre of operetta and became the most popular French composer of his time. Offenbach wrote 100 opera-buffe (operettas) and one unfinished opera, The Tales of Hoffmann, a staple of the opera repertoire. Here’s the overture to La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein. It’s not serious music, and was composed to be light, but the orchestration is quote brilliant and the whole piece is a lot of fun. In this recording the Philharmonia Orchestra is conducted by Sir Neville Marriner. (By the way, the librettists of La Grande-Duchesse were Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy – Halévy was the nephew of another French Jewish composer Fromental Halévy; Meilhac and Halévy also co-wrote the libretto for the famous Carmen.)

The composer who towers over all of the above is Igor Stravinsky, born June 17th of 1882. Please check our previous entries as there are many, for example here, here and here.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: June 8, 2020. Charles Wuorinen. Robert Schumann’s 210th anniversary is today: he was born on June 8th of 1810 in Zwickau, Germany. He is without a doubt one of the greatest composers of all time, and we’ve written about him many times. Many musicologists and regular listeners believe that Schumann’s best work was composed early in his life, and he was suffering greatly by the end of it (he died at just 46 years old in a mental institution). Despite all the depressions and hallucinations, Schumann continued to compose till almost the very end of his life. His last piano composition, called Geistervariationen (Ghost Variations) was written in 1854. At that time Schumann thought that he was surrounded by spirits who played him music, “both "wonderful" and "hideous".” Soon after he was admitted to the mental hospital in Endenich, a suburb of Bonn. He died there two years later. Here is a wonderful young pianist Igor Levit playing Geistervariationen.

doubt one of the greatest composers of all time, and we’ve written about him many times. Many musicologists and regular listeners believe that Schumann’s best work was composed early in his life, and he was suffering greatly by the end of it (he died at just 46 years old in a mental institution). Despite all the depressions and hallucinations, Schumann continued to compose till almost the very end of his life. His last piano composition, called Geistervariationen (Ghost Variations) was written in 1854. At that time Schumann thought that he was surrounded by spirits who played him music, “both "wonderful" and "hideous".” Soon after he was admitted to the mental hospital in Endenich, a suburb of Bonn. He died there two years later. Here is a wonderful young pianist Igor Levit playing Geistervariationen.

Erwin Schulhoff was also bon on this day, in 1894. We’ve never had a chance to write about him; he was one of many European composers who perished during the Holocaust. Schulhoff was born in Prague into a German-Jewish family. Politically, a highly complicated figure but a very talented composer, he died in a German concentration camp in 1942. Here’s his Quartet no. 1, performed by the Kocian Quartet. We owe Schulhoff a separate entry; it will be coming soon.

Today is a special day, as yet another composer, an Italian from the Baroque era, Tomaso Albinoni was also born on this day in 1671. He was famous in his day as a composer of many operas. Now, unfortunately, he’s mostly known for the Adagio in G minor, which he actually didn’t write: it was composed by his biographer, Remo Giazotto, probably based on excerpts from Albinoni’s works.

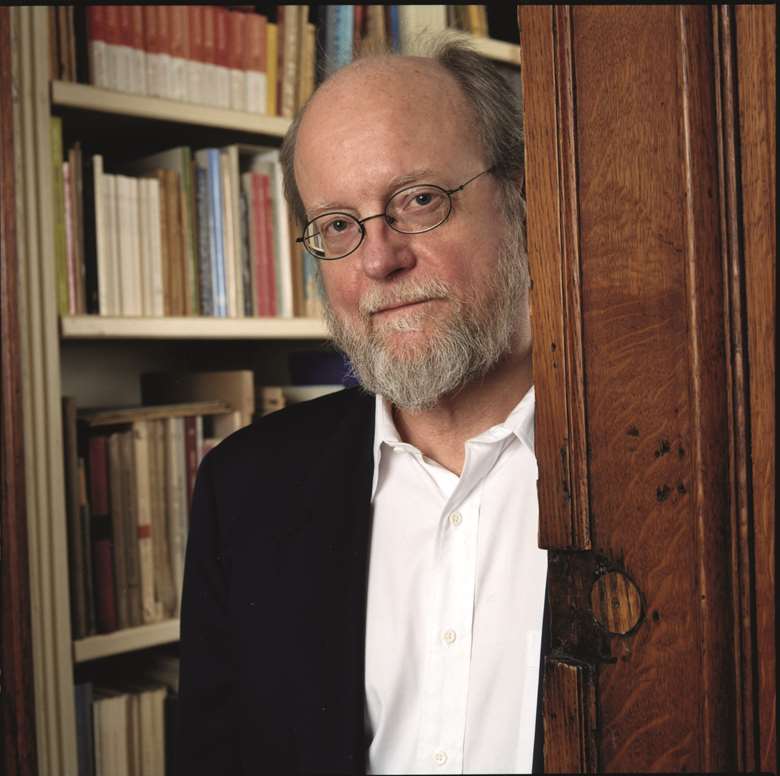

The composer we’d like to commemorate today is Charles Wuorinen, who died less than three months ago, on March 11th of 2020 at the age of 81. Wuorinen (pronounce WOrinen) was born on June 9th of 1938 in Manhattan; his father was a prominent Finnish-American historian. Charles wrote his first compositions at the age of five. In 1962 Wuorinen formed an ensemble, The Group for Contemporary Music, which performed the music of modernist American composers of the day such as Milton Babbitt, Elliott Carter and Stefan Wolpe, as well as the music of Wuorinen himself. In 1970s he taught at the Manhattan School of Music. As many composers of his age, he experimented with electronic music, at some point in the 1970s even getting a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to conduct sonic experiments at AT&T’s Bell Labs. In 2000s James Levine became a champion of Wuorinen’s music and commissioned a piano concerto (his fourth). Overall, Wuorinen composed about 270 pieces, including an opera, Brokeback Mountain (2015). Wuorinen had many supporter (the pianist Peter Serkin for one) and almost as many detractors, the renowned musicologist Richard Taruskin being one of them. Here’s Wuorinen’s very interesting Piano Concerto no. 3, performed by one his champions, the pianist Garrick Ohlsson and the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra conducted by Herbert Blomsted.Permalink

months ago, on March 11th of 2020 at the age of 81. Wuorinen (pronounce WOrinen) was born on June 9th of 1938 in Manhattan; his father was a prominent Finnish-American historian. Charles wrote his first compositions at the age of five. In 1962 Wuorinen formed an ensemble, The Group for Contemporary Music, which performed the music of modernist American composers of the day such as Milton Babbitt, Elliott Carter and Stefan Wolpe, as well as the music of Wuorinen himself. In 1970s he taught at the Manhattan School of Music. As many composers of his age, he experimented with electronic music, at some point in the 1970s even getting a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to conduct sonic experiments at AT&T’s Bell Labs. In 2000s James Levine became a champion of Wuorinen’s music and commissioned a piano concerto (his fourth). Overall, Wuorinen composed about 270 pieces, including an opera, Brokeback Mountain (2015). Wuorinen had many supporter (the pianist Peter Serkin for one) and almost as many detractors, the renowned musicologist Richard Taruskin being one of them. Here’s Wuorinen’s very interesting Piano Concerto no. 3, performed by one his champions, the pianist Garrick Ohlsson and the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra conducted by Herbert Blomsted.Permalink