Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

This Week in Classical Music: October 5, 2020. An unusual week. Last week, unfortunately, we had two days of outages. This had to do with our hosting provider updating some software, but part of the problem was with us: we also need to keep up with evolving technology. For that we’ll need some help from our listeners. More on this tropic to come.

This coming week is quite bountiful: three composers, three pianists, one cellist (but what a cellist!) and a conductor. First, the composers - a German, an Italian, and a Frenchman: Heinrich Schütz, Giuseppe Verdi and Camille Saint-Saëns. We’ve celebrated all of them many times, Schütz, probably the most important German composer before Bach, here and here; Verdi – many times (take a look here and here). We were more circumspect about Saint-Saëns: a fine composer, quite conservative at that: he died in 1921, ten years after Mahler, when Stravinsky has already written many of the masterpieces of his Russian period, after the Viennese school forever changed the way we would listen to music – and he was writing things like this Oboe Sonata in D major, op. 166, from 1921, the year of his death. A charming piece, but one that wouldn’t be out of place half a century earlier. In this performance Guido Ghetti is the oboist and Amadeo Salvato is on the piano.

cellist!) and a conductor. First, the composers - a German, an Italian, and a Frenchman: Heinrich Schütz, Giuseppe Verdi and Camille Saint-Saëns. We’ve celebrated all of them many times, Schütz, probably the most important German composer before Bach, here and here; Verdi – many times (take a look here and here). We were more circumspect about Saint-Saëns: a fine composer, quite conservative at that: he died in 1921, ten years after Mahler, when Stravinsky has already written many of the masterpieces of his Russian period, after the Viennese school forever changed the way we would listen to music – and he was writing things like this Oboe Sonata in D major, op. 166, from 1921, the year of his death. A charming piece, but one that wouldn’t be out of place half a century earlier. In this performance Guido Ghetti is the oboist and Amadeo Salvato is on the piano.

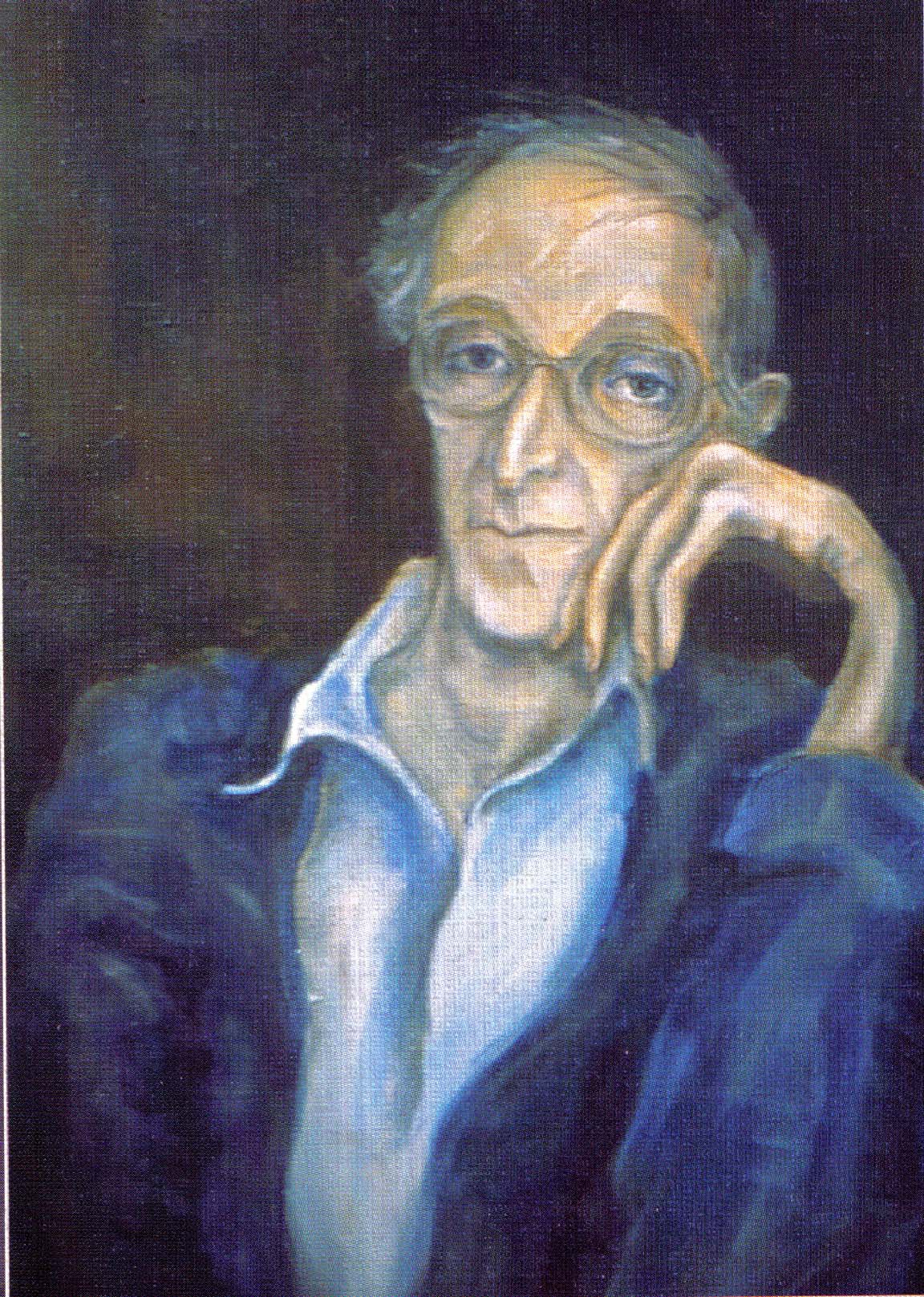

Speaking of the piano: three distinguished pianists were born this week, Edwin Fischer, Shura Cherkassky, and Evgeny Kissin. Edwin Fischer, a Swiss pianist, was born in 1886 but, fortunately, left a number of remarkable recording, especially those of Mozart and Bach. Shura Cherkassky was born in Odessa in 1909 and performed for almost 70 years: he started performing publicly in 1928, his last recording was made in 1995, the year of his death, when Cherkassky was 85. Shura (diminutive from Alexander) came to the US in 1923 and studied with Josef Hoffman. He moved to London after WWII. The music critic Harold Schonberg called Cherkassky “the last remaining exponent of the grand Romantic style.” Here’s a live recording of Cherkassky playing Rachmaninov’s Variations on a Theme of Corelli. It was made in 1986. As for Evgeny Kissin, who will turn 50 next year: we hope that both he and we are up and running and we’ll have a chance to dedicate a full entry to this extraordinary pianist.

week, Edwin Fischer, Shura Cherkassky, and Evgeny Kissin. Edwin Fischer, a Swiss pianist, was born in 1886 but, fortunately, left a number of remarkable recording, especially those of Mozart and Bach. Shura Cherkassky was born in Odessa in 1909 and performed for almost 70 years: he started performing publicly in 1928, his last recording was made in 1995, the year of his death, when Cherkassky was 85. Shura (diminutive from Alexander) came to the US in 1923 and studied with Josef Hoffman. He moved to London after WWII. The music critic Harold Schonberg called Cherkassky “the last remaining exponent of the grand Romantic style.” Here’s a live recording of Cherkassky playing Rachmaninov’s Variations on a Theme of Corelli. It was made in 1986. As for Evgeny Kissin, who will turn 50 next year: we hope that both he and we are up and running and we’ll have a chance to dedicate a full entry to this extraordinary pianist.

Yo-Yo Ma is our cellist of the week. He was born on October 7th, 1955 in Paris to Chinese parents; his family moved to New York when Ma was seven. A child prodigy, he played several instruments from a very early age but eventually (by the age of seven!) settled on the cello. He studied with Leonard Rose at the Juilliard. When Ma was 15, Leonard Bernstein presented him on one of his TV programs. Since 1976 he’s been performing widely and is now consider one of the greatest cellists of his generation. He’s played with all major orchestras and distinguished instrumentalists, such as the violinists Pinchas Zukerman and Yehudi Menuhin and the pianist Emanuel Ax. Ma’s recorded repertoire is wide, and his recordings of Bach’s cello sonatas are especially highly valued.

And finally, our conductor of the week: Theodore Thomas, born on October 11th of 1835; he was the first music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Thomas was born in Essen, Germany but his family moved to the US when he was 10. He had a distinguished career as a conductor and came to Chicago after being promised a permanent orchestra. Under his direction, the Chicago Orchestra played its first concert on October 16th of 1891. In December of 1904 he opened Symphony Hall, designed by Daniel Burnham. Theodore Thomas died of pneumonia on January 4th, 1905 after conducting just two weeks of subscription concerts at the new hall.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: September 28, 2020. Instrumentalists. While there are no significant dates associated with composers this week, there are plenty of wonderful names to celebrate among the people who interpret composers’ music. Let’s start with the pianists. Vladimir Horowitz was born on October 1st of 1903 in Kiev, Ukraine, (then the Russian Empire) into a well-off Jewish family (Horowitz’s grandfather had a special merchant rank that allowed him to live outside of the Pale of Settlement; after the Revolution their assets were expropriated and the family impoverished). At the age of nine Horowitz entered the Kiev Conservatory where he studied with Felix Blumenfeld, among others. He made his solo debut in 1920; around that time, he met the violinist Nathan Milstein, who was the same age and showed great talent. They played together in concerts (Vladimir’s sister Regina was Milstein’s accompanist). Both Horowitz and Milstein left Russia in 1925; Vladimir went first to Berlin and then to the US. His debut, on January 12th of 1928, when he played Tchaikovsky’s First piano concerto faster than Thomas Beecham would have it and dazzled the public with his technique, became legendary. That was the beginning of one of the most brilliant pianist careers of the 20th century, even though Horowitz interrupted it four times, first from 1936 to 1938, then from 1953 to 1965, his longest absence from the concert stage, and again in 1969–74 and 1983–85. Altogether, he was away from the public for a long 21 years. That didn’t prevent him from becoming both a celebrity and one of the most interesting pianists of the century.

celebrate among the people who interpret composers’ music. Let’s start with the pianists. Vladimir Horowitz was born on October 1st of 1903 in Kiev, Ukraine, (then the Russian Empire) into a well-off Jewish family (Horowitz’s grandfather had a special merchant rank that allowed him to live outside of the Pale of Settlement; after the Revolution their assets were expropriated and the family impoverished). At the age of nine Horowitz entered the Kiev Conservatory where he studied with Felix Blumenfeld, among others. He made his solo debut in 1920; around that time, he met the violinist Nathan Milstein, who was the same age and showed great talent. They played together in concerts (Vladimir’s sister Regina was Milstein’s accompanist). Both Horowitz and Milstein left Russia in 1925; Vladimir went first to Berlin and then to the US. His debut, on January 12th of 1928, when he played Tchaikovsky’s First piano concerto faster than Thomas Beecham would have it and dazzled the public with his technique, became legendary. That was the beginning of one of the most brilliant pianist careers of the 20th century, even though Horowitz interrupted it four times, first from 1936 to 1938, then from 1953 to 1965, his longest absence from the concert stage, and again in 1969–74 and 1983–85. Altogether, he was away from the public for a long 21 years. That didn’t prevent him from becoming both a celebrity and one of the most interesting pianists of the century.

Vera Gornostayeva was practically unknown in the West, even though she was highly regarded by first the Soviet and then the Russian musical community as a very talented and “thinking” musician. She was also born on October 1st, in 1929, in Moscow. She studied with Heinrich Neuhaus at the Moscow Conservatory and then taught there for 50 years. One of her pupils, Vassily Primakov, was instrumental in publishing Gornostayeva’s CDs and bringing her art to the attention of the American public. She became a favorite of the listeners of WFMT, a Chicago classical music station. Gornostayeva had many students, among them Alexander Slobodyanik, Eteri Andjaparidze and Sergei Babayan.

David Oistrakh was also born this week, on September 30th of 1908. As a violinist he occupies a place in the musical pantheon similar to Horowitz. Oistrakh was bon in Odessa, that cradle of Jewish violin virtuosos. Oistrakh studied with Pyotr Stolyarsky, as did Nathan Milstein, and played a concert with him in 1914. Oistrakh made his big debut in Leningrad in 1928, the year Horowitz made his debut in New York. In the 1930s the Soviets were keen to demonstrate their cultural achievement, and music competitions became politically important. Oistrakh excelled in them, winning many (among them the first prize in the prestigious Concours Eugène Ysaÿe in Brussels in 1937) and earned accolades at home and abroad. Oistrakh was one of the first Soviet musicians to travel to the West – he was allowed to play in Finland in 1949. In 1955 he went to the US for the first time, playing, to great acclaim, Shostakovich’s First Violin concerto, which the composer dedicated to him. Oistrach was a wonderful interpreter of the music of Bach. here’s Bach’s Violin Concerto no. 1 in A minor. David Oistrakh is accompanied by the Vienna Symphony, Georg Fischer conducting.Permalink

a place in the musical pantheon similar to Horowitz. Oistrakh was bon in Odessa, that cradle of Jewish violin virtuosos. Oistrakh studied with Pyotr Stolyarsky, as did Nathan Milstein, and played a concert with him in 1914. Oistrakh made his big debut in Leningrad in 1928, the year Horowitz made his debut in New York. In the 1930s the Soviets were keen to demonstrate their cultural achievement, and music competitions became politically important. Oistrakh excelled in them, winning many (among them the first prize in the prestigious Concours Eugène Ysaÿe in Brussels in 1937) and earned accolades at home and abroad. Oistrakh was one of the first Soviet musicians to travel to the West – he was allowed to play in Finland in 1949. In 1955 he went to the US for the first time, playing, to great acclaim, Shostakovich’s First Violin concerto, which the composer dedicated to him. Oistrach was a wonderful interpreter of the music of Bach. here’s Bach’s Violin Concerto no. 1 in A minor. David Oistrakh is accompanied by the Vienna Symphony, Georg Fischer conducting.Permalink

We’ve written about every single one of them, but this week we’d like to compensate for a significant date we missed last week. September 19th marked the 100th anniversary of the birth of Alexander Lokshin, a very talented Soviet composer whose tragic life in a way mirrors the history of his native country. Lokshin was born in Biysk, a city in Altai, southern Siberia, into a Jewish family. When Alexander was ten, the family moved to Novosibirsk, a much larger and culturally developed city, where Alexander attended a music school. In 1936 Lokshin went to Moscow and eventually was accepted at the Moscow Conservatory, the composition class of Nikolai Myaskovsky. In 1939, for his graduation, Lokshin wrote a symphonic piece with a vocal part based on Charles Baudelaire’s cycle Les Fleurs du Mal. In the 1939 Soviet Union Baudelaire was considered “bourgeois,” and even though the work was performed by the noted conductor Nikolai Anosov, Lokshin was denied a diploma and eventually kicked out of the Conservatory. But things worked unpredictably in the Soviet Union, where an official could be promoted and then executed a couple months later. In this case, Lokshin was lucky: Myaskovsky wrote a glowing letter of recommendation and in 1941, despite his troubles at the Conservatory, Lokshin was admitted to the official Composers’ Union. As the war started Lokshin volunteered to join the army but was soon dismissed because of poor health (he had terrible stomach problems). He moved back to Novosibirsk, where his family was living in poverty and his father was dying. In Novosibirsk Lokshin had several menial jobs and continued composing. In 1943 one of his works, a vocal-symphonic poem Wait for me (the words were based on a very popular poem by Konstantin Simonov), was performed by the Leningrad Symphony under the direction of Yevgeny Mravinsky, then touring Novosibirsk. The work was praised in musical circles and Lokshin was readmitted to Moscow Conservatory where Wait for me was accepted as his graduation work. In 1945 Lokshin was given a low-level job at the Conservatory, but three years later, in 1948, during Stalin’s antisemitic campaign against “Cosmopolitism” (read against the Jews), he was fired. Even though Myaskovsky and the pianist Maria Yudina, whom Stalin liked, tried to help him, he couldn’t find a job. For the rest of his life he had practically no income, and was supported by his wife, Tatyana Alisova, a specialist in Italian literature. Lokshin himself said that his serious compositional work started only in 1957, when he wrote his First Symphony (“Requiem”) which Shostakovish considered a work of genius. Such conductors as Gennady Rozhdestvensky and Rudolf Barshai were Lokshin’s champions. The last years of Lokshin’s life were marred by accusations that he was a KGB agent and that his denunciations led to arrests of several people. Many in intelligentsia turned away from Lokshin and Rozhdestvensky stopped playing his music. Some years later Lokshin’s son Alexander collected documents that seem to prove that Lokshin was discredited by the KGB to cover for a real agent. Lokshin died in Moscow on June 11th of 1987, his music practically forgotten. It still is rarely performed.

We’ve written about every single one of them, but this week we’d like to compensate for a significant date we missed last week. September 19th marked the 100th anniversary of the birth of Alexander Lokshin, a very talented Soviet composer whose tragic life in a way mirrors the history of his native country. Lokshin was born in Biysk, a city in Altai, southern Siberia, into a Jewish family. When Alexander was ten, the family moved to Novosibirsk, a much larger and culturally developed city, where Alexander attended a music school. In 1936 Lokshin went to Moscow and eventually was accepted at the Moscow Conservatory, the composition class of Nikolai Myaskovsky. In 1939, for his graduation, Lokshin wrote a symphonic piece with a vocal part based on Charles Baudelaire’s cycle Les Fleurs du Mal. In the 1939 Soviet Union Baudelaire was considered “bourgeois,” and even though the work was performed by the noted conductor Nikolai Anosov, Lokshin was denied a diploma and eventually kicked out of the Conservatory. But things worked unpredictably in the Soviet Union, where an official could be promoted and then executed a couple months later. In this case, Lokshin was lucky: Myaskovsky wrote a glowing letter of recommendation and in 1941, despite his troubles at the Conservatory, Lokshin was admitted to the official Composers’ Union. As the war started Lokshin volunteered to join the army but was soon dismissed because of poor health (he had terrible stomach problems). He moved back to Novosibirsk, where his family was living in poverty and his father was dying. In Novosibirsk Lokshin had several menial jobs and continued composing. In 1943 one of his works, a vocal-symphonic poem Wait for me (the words were based on a very popular poem by Konstantin Simonov), was performed by the Leningrad Symphony under the direction of Yevgeny Mravinsky, then touring Novosibirsk. The work was praised in musical circles and Lokshin was readmitted to Moscow Conservatory where Wait for me was accepted as his graduation work. In 1945 Lokshin was given a low-level job at the Conservatory, but three years later, in 1948, during Stalin’s antisemitic campaign against “Cosmopolitism” (read against the Jews), he was fired. Even though Myaskovsky and the pianist Maria Yudina, whom Stalin liked, tried to help him, he couldn’t find a job. For the rest of his life he had practically no income, and was supported by his wife, Tatyana Alisova, a specialist in Italian literature. Lokshin himself said that his serious compositional work started only in 1957, when he wrote his First Symphony (“Requiem”) which Shostakovish considered a work of genius. Such conductors as Gennady Rozhdestvensky and Rudolf Barshai were Lokshin’s champions. The last years of Lokshin’s life were marred by accusations that he was a KGB agent and that his denunciations led to arrests of several people. Many in intelligentsia turned away from Lokshin and Rozhdestvensky stopped playing his music. Some years later Lokshin’s son Alexander collected documents that seem to prove that Lokshin was discredited by the KGB to cover for a real agent. Lokshin died in Moscow on June 11th of 1987, his music practically forgotten. It still is rarely performed.

This Week in Classical Music: September 21, 2020. Alexander Lokshin. Several great composers were born this week: Jean-Philippe Rameau, for example, on September 25th of 1683, or Dmitry Shostakovich, on the same day in 1906. George Gershwin was born on September 26th of 1898. Komitas, the national composer of Armenia, was also born on the 26th, in 1869, while Mikalojus Čiurlionis, who occupies a similar place in the musical history of Lithuania, was born on September 22nd of 1875. And let’s not forget Andrzej Panufnik, one of the most interesting Polish composer of the 20th century: he was born on September 24th of 1914.

Lokshin is most interesting in his symphonic pieces, but here is an example of his piano music, Variations, in the performance by Maria Grinberg, a pianist who had also suffered terribly under the Stalin regime.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: September 14, 2020. Cherubini. Luigi Cherubini may have been born on this day in 1760, in Florence, or he may have been born on the 8th, we’ll never know for sure. What we do know is that Beethoven held him in high esteem, proclaiming him to be the greatest composer – other than himself, of course. This is especially interesting considering that Cherubini, ten years his elder, openly disliked Beethoven’s opera Fidelio, which he heard during its premier in Vienna in 1805, and considered his piano music “rough.” And Beethoven was not his only admirer: Haydn and Rossini liked him too. Cherubini, who moved to Paris permanently in 1786, was for a time considered the premier opera composer. During his life he wrote almost 40 pieces in this genre, very few of which are performed these days. Later in his career Cherubini turned to church music, writing masses and two requiems (Beethoven greatly admired the first one, in C minor, written in 1816). As he grew older, Cherubini’s musical output diminished (at that time he wrote mostly instrumental music), but not his influence, as in 1822 he became the director of the Paris Conservatory. Cherubini died in Paris on March 15th of 1842. Here are Introitus et Kyrie from Cherubini’s Requiem in C minor, which Beethoven enjoyed so much. Martin Pearlman leads the Boston Baroque.

for sure. What we do know is that Beethoven held him in high esteem, proclaiming him to be the greatest composer – other than himself, of course. This is especially interesting considering that Cherubini, ten years his elder, openly disliked Beethoven’s opera Fidelio, which he heard during its premier in Vienna in 1805, and considered his piano music “rough.” And Beethoven was not his only admirer: Haydn and Rossini liked him too. Cherubini, who moved to Paris permanently in 1786, was for a time considered the premier opera composer. During his life he wrote almost 40 pieces in this genre, very few of which are performed these days. Later in his career Cherubini turned to church music, writing masses and two requiems (Beethoven greatly admired the first one, in C minor, written in 1816). As he grew older, Cherubini’s musical output diminished (at that time he wrote mostly instrumental music), but not his influence, as in 1822 he became the director of the Paris Conservatory. Cherubini died in Paris on March 15th of 1842. Here are Introitus et Kyrie from Cherubini’s Requiem in C minor, which Beethoven enjoyed so much. Martin Pearlman leads the Boston Baroque.

Frank Martin, a Swiss composer who lived most of his live in the Netherlands, was also born this week, on September 15th of 1890, in Geneva. He started composing at the age of eight but never went to a conservatory. He even started studying physics and mathematics, following his parent’s wishes, but eventually abandoned his studies. Martin’s music style was influenced by many, from Bach to Schumann to the modernists. Eventually he settled on a mostly harmonic approach, with some 12-tone technique thrown in for good measure. A bit like Cherubini, later in his career Martin wrote a number of sacred pieces, some choral, some for the organ, and, like Cherubini, he wrote a Requiem. He died in Naarden, Holland, on November 21st of 1974. Here’s Frank Martin’s Petite Symphonie Concertante, from 1944. Armin Jourdan leads the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande.

The great conductor Bruno Walter was also born this week, on September 15th of 1876. We celebrated him last year. And the incomparable Jessye Norman was also born on September 15th, in 1945. In two weeks will be the one-year anniversary of her death. It was a great loss.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: September 7, 2020. Purcell. Henry Purcell was born on September 10th of 1659 during the last year of Interregnum: Oliver Cromwell, who ruled England as Lord Protector, died a year earlier, in 1658, and Charles II, the son of the executed King Charles I would return to London a year later and be coronated in 1561; Henry’s father, Henry Purcell Sr., a musician, would sing at the Westminster Abbey during the ceremony. Henry Jr’s uncle Thomas was a musician at the Chapel Royal and through him Henry was admitted there as a chorister. Purcell studied with noted musicians, first John Blow and Christopher Gibbons and later with Matthew Locke, who was "Private Composer-in-Ordinary to the King Charles II." Purcell started composing early, his first known composition dates around 1670. By 1677, when he replaced Locke as the court composer, he had written several “Anthems” and other sacred music (at that time, he was writing few instrumental pieces). Many of Purcell’s compositions were created for the Westminster Abbey, although the Abbey paid him mostly for his services as an organ tuner. In 1679 Purcell succeeded John Blow as organist at the Abbey and held that position for the rest of his short life (he died at the age of 36). In 1682 Purcell was admitted as a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal where he performed as one of the organists. In 1685 Charles II died and his younger brother James II became king. For James’s coronation Purcell wrote the anthem “My heart is inditing of a Good Matter.” Here it is, performed by the Collegium Vocale Ghent under the direction of Philippe Herreweghe. Under James, who was a Catholic, the court music was reorganized, and Purcell’s activities were reduced. In 1688 James was deposed during the Glorious Revolution. William III and Mary II ascended to the throne, but they weren’t interested in music as much as the preceding Stuarts. Purcell refocused his attention on music theater, though he continued to compose odes for Queen Mary. He wrote music for Dryden’s tragedy Tyrannick Love, a three-act opera Dido and Aeneas, for the then popular play The Fool's Preferment and several others. In 1692 he composed music to The Fairy-Queen, after Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night's Dream. He started working on another Dryden’s play, The Indian Queen, but never finished it: he died of an unknown illness on November 21st of 1695. His younger brother Daniel completed the last act of the opera. Purcell was buried at the Westminster Abbey, next to the organ he played for many years. Purcell’s own Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary was played during the ceremony.

as Lord Protector, died a year earlier, in 1658, and Charles II, the son of the executed King Charles I would return to London a year later and be coronated in 1561; Henry’s father, Henry Purcell Sr., a musician, would sing at the Westminster Abbey during the ceremony. Henry Jr’s uncle Thomas was a musician at the Chapel Royal and through him Henry was admitted there as a chorister. Purcell studied with noted musicians, first John Blow and Christopher Gibbons and later with Matthew Locke, who was "Private Composer-in-Ordinary to the King Charles II." Purcell started composing early, his first known composition dates around 1670. By 1677, when he replaced Locke as the court composer, he had written several “Anthems” and other sacred music (at that time, he was writing few instrumental pieces). Many of Purcell’s compositions were created for the Westminster Abbey, although the Abbey paid him mostly for his services as an organ tuner. In 1679 Purcell succeeded John Blow as organist at the Abbey and held that position for the rest of his short life (he died at the age of 36). In 1682 Purcell was admitted as a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal where he performed as one of the organists. In 1685 Charles II died and his younger brother James II became king. For James’s coronation Purcell wrote the anthem “My heart is inditing of a Good Matter.” Here it is, performed by the Collegium Vocale Ghent under the direction of Philippe Herreweghe. Under James, who was a Catholic, the court music was reorganized, and Purcell’s activities were reduced. In 1688 James was deposed during the Glorious Revolution. William III and Mary II ascended to the throne, but they weren’t interested in music as much as the preceding Stuarts. Purcell refocused his attention on music theater, though he continued to compose odes for Queen Mary. He wrote music for Dryden’s tragedy Tyrannick Love, a three-act opera Dido and Aeneas, for the then popular play The Fool's Preferment and several others. In 1692 he composed music to The Fairy-Queen, after Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night's Dream. He started working on another Dryden’s play, The Indian Queen, but never finished it: he died of an unknown illness on November 21st of 1695. His younger brother Daniel completed the last act of the opera. Purcell was buried at the Westminster Abbey, next to the organ he played for many years. Purcell’s own Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary was played during the ceremony.

Several important composers were also born this week, among them Girolamo Frescobaldi (on September 13th of 1583, in Ferrara). And isn’t it surprising that Arnold Schoenberg (September 13th of 1874) was only 33 years younger than Antonin Dvořák (September 13th of 1841)? Musically, they belong to different eras.Permalink

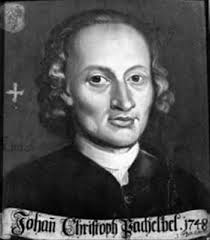

This Week in Classical Music: August 31, 2020. Cornucopia. Last week was rather disappointing, we had to go back several centuries to find a composer of interest, but look how different it is this week. Of the first-rate composers, the oldest is . Yes, he was absolutely first rate: not just the author of the ubiquitous Canon but the composer of the influential Hexachordum Apollinis, a wonderful collection of tkeyboard music. Please check out our library, we have all six Arias with variations there. Pachelbel was born on September 1st of 1653.

. Yes, he was absolutely first rate: not just the author of the ubiquitous Canon but the composer of the influential Hexachordum Apollinis, a wonderful collection of tkeyboard music. Please check out our library, we have all six Arias with variations there. Pachelbel was born on September 1st of 1653.

Pietro Locatelli, an Italian Baroque composer and violinist, was born on September 3rd of 1695. Not a great figure in the history of music, but some of his violin sonatas and concerti were pleasant. And then, a very different figure, Anton Bruckner, one of the greatest composers of the 19th century, sometimes underappreciated but at the peak of recognition these days – and rightfully so. Bruckner was born on September 4th of 1824.

Jumping forward: Darius Milhaud. He was also born on September 4th, of 1892. A member of Les Six, he wrote in many different styles, from jazz to polytonality. As a Jew, he had to flee France during the occupation and spent several years in the US. Here’s Milhaud’s Quartet no. 15, op. 291 performed by the Quatuor Parisii.

Moving on, or for the moment back, here’s Johann Christian Bach, the eighteenth (yes, eighteenth!) offspring of Johann Sebastian Bach; by the time he moved to England and became famous there (he would be called "the London Bach” or "the English Bach"), around 1766, only seven of his siblings were still alive. Johann Christian, born on September 5th of 1735, was the youngest of Johann Sebastian’s composer kids. He did much to further the new “Classical” style.

And that’s not all: Giacomo Meyerbeer, Amy Beach, and John Cage were also born this week. That makes three centuries of music, from the late 17th to the second half of the 20th.

That is as far as the composers go, but then there are three conductors, Tullio Serafin, Leonard Slatkin and Seiji Ozawa, all born on September 1st: Serafin, a great opera conductor, in 1878, Ozawa in 1935 and Slatkin in1944. But that’s not all: Itzhak Perlman also has his birthday this week. Can you imagine that he’s going to turn 75? Perlman was born on this day in 1945. You may have your qualms, but all in all he is one of the greatest violinists of the end of the 20th century. Nobody matched the beauty of his tone when Perlman performed at his best. Here’s Perlman and Vladimir Ashkenazy playing Beethoven’s Violin Sonata No. 4 in A Minor, Op. 23.Permalink

Tullio Serafin, Leonard Slatkin and Seiji Ozawa, all born on September 1st: Serafin, a great opera conductor, in 1878, Ozawa in 1935 and Slatkin in1944. But that’s not all: Itzhak Perlman also has his birthday this week. Can you imagine that he’s going to turn 75? Perlman was born on this day in 1945. You may have your qualms, but all in all he is one of the greatest violinists of the end of the 20th century. Nobody matched the beauty of his tone when Perlman performed at his best. Here’s Perlman and Vladimir Ashkenazy playing Beethoven’s Violin Sonata No. 4 in A Minor, Op. 23.Permalink