Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

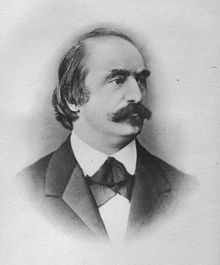

October 9, 2017. Verdi, Saint-Saens and more. The great Italian opera composer Giuseppe Verdi was born on this day – or maybe on the following day, October 10th, as we only know that he was baptized on the 11th – in 1813, in Roncole, a small village in the province of Parma. The “national composer” of Italy, Verdi created 25 operas. Not all of them are staged today, but the majority represent the absolute best in the opera repertory. Verdi’s musical genius came into full force when he was approaching 40: just in three years he created three operas which haven’t left the stages of major theaters since their premiers: Rigoletto, first staged in La Fenice in Venice in March of 1851, Il Trovatore, premiered in Rome in 1853, and La Traviata, also in La Fenice in March of 1853. There is so much music in Rigoletto that it could fill several operas: every one of its three acts has something memorable, from Addio, addio and Caro nome in Act I, to Cortigiani, vil razza dannata, Tutte le feste al tempioi and Sì! Vendetta, tremenda vendetta! in Act II, to the ever popular La donna è mobile and the famous quartet Bella figlia dell’amore in Act III and so much more. A fitting tribute to Verdi would be to play the complete Rigoletto, but of course it’s not practical. Instead, we’ll play two excerpts, first, the duet Tutte le feste al tempio (Each holy day, in church) from Act II, with Maria Callas as Gilda and the great baritone Titto Gobbi as Rigoletto; Tullio Serafin conducting the La Scala orchestra in this 1955 recording (here). Then comes Bella figlia dell’amore, with Luciano Pavarotti, Joan Sutherland, Leo Nucci and Isola Jones. Riccardo Chailly conducts the Metropolitan Opera (here).

he was baptized on the 11th – in 1813, in Roncole, a small village in the province of Parma. The “national composer” of Italy, Verdi created 25 operas. Not all of them are staged today, but the majority represent the absolute best in the opera repertory. Verdi’s musical genius came into full force when he was approaching 40: just in three years he created three operas which haven’t left the stages of major theaters since their premiers: Rigoletto, first staged in La Fenice in Venice in March of 1851, Il Trovatore, premiered in Rome in 1853, and La Traviata, also in La Fenice in March of 1853. There is so much music in Rigoletto that it could fill several operas: every one of its three acts has something memorable, from Addio, addio and Caro nome in Act I, to Cortigiani, vil razza dannata, Tutte le feste al tempioi and Sì! Vendetta, tremenda vendetta! in Act II, to the ever popular La donna è mobile and the famous quartet Bella figlia dell’amore in Act III and so much more. A fitting tribute to Verdi would be to play the complete Rigoletto, but of course it’s not practical. Instead, we’ll play two excerpts, first, the duet Tutte le feste al tempio (Each holy day, in church) from Act II, with Maria Callas as Gilda and the great baritone Titto Gobbi as Rigoletto; Tullio Serafin conducting the La Scala orchestra in this 1955 recording (here). Then comes Bella figlia dell’amore, with Luciano Pavarotti, Joan Sutherland, Leo Nucci and Isola Jones. Riccardo Chailly conducts the Metropolitan Opera (here).

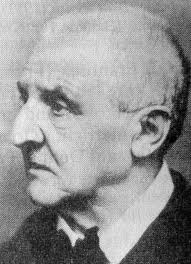

Camille Saint-Saëns was also born on this day, in 1835. A prolific composer, Saint-Saëns lived a long life: he died in 1921, three years after Debussy. While he had major melodic talent, he was a composer of conservative tastes; his music was rather conventional from the beginning; by the end of his life it sounded quite dated. Saint-Saëns wrote in many genres: orchestral music (his Third “Organ” Symphony is still popular), five piano concertos (the Second is regularly performed), three violin concertos, one concerto for the cello, and several operas, one of which, Samson and Dalilah is still staged quite often. We can “compare and contrast” it with Rigoletto: here’s Dalilah’s aria, performed by Maria Callas in 1961, the same Callas as we heard in Tutte le feste. By then her voice was not the same; still, it’s a lovely performance, and so is the music. Georges Prêtre conducts The French National Radio Orchestra.

One of the greatest pianists of his generation, Evgeny Kissin was born on October 10th of 1971 in Moscow. He entered the Gnessin Music School at the age of 6. His first, and, amazingly, only teacher was Anna Kantor. He was 10 when he publicly played his first piano concerto (Mozart’s Twentieth); at the age of 12 he played Chopin’s First and Second concertos at the Great Hall of Moscow Conservatory. In 1988 he famously played Tchaikovsky’s First with Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic. He made his American debut in 1990, a year later he moved to New York. In the subsequent years he also lived in London and Paris, and, since marrying his childhood friend Karina Arzumanova, he moved to Prague. Here he plays Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No.2 in G Minor Op.16. Vladimir Ashkenazy conducts the Philharmonia Orchestra.Permalink

The Eighth Symphony was begun immediately after the completion of the Seventh. Its manuscript, which escaped the fate of that of its predecessor, is dated October 1812, meaning it was completed in a roughly four-month span. This makes it an exception to Beethoven’s usual method of composing, since his symphonies were usually sketched during the summer months, then worked out and put into full score during the winter in Vienna.

The Eighth Symphony was begun immediately after the completion of the Seventh. Its manuscript, which escaped the fate of that of its predecessor, is dated October 1812, meaning it was completed in a roughly four-month span. This makes it an exception to Beethoven’s usual method of composing, since his symphonies were usually sketched during the summer months, then worked out and put into full score during the winter in Vienna.

October 2, 2017. Beethoven Symphony No. 8. This week we’re publishing Joseph DuBose’s article on Symphony no. 8 in F major by Ludwig van Beethoven. And again, as with all other symphonies, the problem is in selecting a performance to illustrate the article: there are too many great ones. We decided on the 1978 recording made by Herbert von Karajan with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. You can listen to it here. The 1st movement is Allegro vivace e con brio (0:01), the 2nd, Allegretto scherzando starts at 9:21, the 3rd, Tempo di menuetto -- at 13:18, and the 4th, Allegro vivace -- at 19:16. ♫

What is truly remarkable of the work is its humorous disposition considering the events that were then taking place in Beethoven’s life. In this manner, it is like the ebullient Second that so completely and effortlessly masked the inner torment that found its outlet in the famous Heiligenstadt Testament. Besides his increasing deafness, Beethoven’s health was already becoming problematic by this point in his life. Yet, of further grief to the composer was a quarrel with his brother Johann. Johann had been living with a woman named Therese Obermeyer, whom Beethoven absolutely loathed and disparagingly nicknamed “Queen of the Night.” Beethoven set out with the singular purpose of putting an end to the relationship. For what reason other than his disdain for Obermeyer is not known, but his actions certainly give credit to Goethe’s description of Beethoven as “an entirely uncontrolled person.” The confrontation between the two brothers was in all probability a mighty din. To Beethoven’s chagrin, Johann emerged the victor when he married Therese Obermeyer on November 8th. Yet, despite this family feud, Beethoven enjoyed pleasant accommodations at his brother’s house, and the surrounding landscape provided him with ample scenery for his many romps through nature. Progress on the Eighth Symphony was unhindered, though some of its passages, no doubt, did not escape Beethoven’s furious temper at this time. (Continue reading here).Permalink

September 25, 2017. Rameau and Shostakovich. It is rather unfortunate that Jean-Philippe Rameau, the great French composer, and Dmitry Shostakovich, one of the most important Soviet composers, were born on the same day, September 25th, one in 1683, another almost two and a half centuries later, in 1906. So different were the societies into which they were born, the cultures, the prevailing musical styles that it’s almost impossible to write about them in one post. The only thing that their lives had in common is that both lived in absolutist countries: Rameau, under the benign regimes of Louis XIV and his great-grandson, Lois XV, Shostakovich – under the murderous one of Stalin.

composers, were born on the same day, September 25th, one in 1683, another almost two and a half centuries later, in 1906. So different were the societies into which they were born, the cultures, the prevailing musical styles that it’s almost impossible to write about them in one post. The only thing that their lives had in common is that both lived in absolutist countries: Rameau, under the benign regimes of Louis XIV and his great-grandson, Lois XV, Shostakovich – under the murderous one of Stalin.

We know surprisingly little about Rameau’s first 40 years. He was born in Dijon. His father was an organist and gave Jean-Philippe music lessons, starting at an early age. Jean-Philippe studied at the Jesuit Collège des Godrans in Dijon. After finishing school, he went on a short trip to Italy, and stayed in Milan. In 1702, he was appointed a music master at the Cathedral of Notre Dame des Doms in Avignon and stayed there for four years. After that, he worked in several provincial towns, before returning to Dijon in 1709 to take his father’s position as the organist at Notre Dame. He eventually moved to Clermont to work as an organist there. We know that during those years he was already composing, most likely motets, but nothing significant has survived.

In 1722 Rameau moved to Paris, the only place in centralized France where a musician could build a significant career. As a composer, he was practically unknown. His first step was to publish Traité de l'harmonie, a work on music theory, which was soon followed by the Nouveau système de musique théorique, another theoretical work that made him famous not only in France, but in England as well. He continued to compose but mostly for the harpsichord, although he was already interested in writing operas (circumstances wouldn’t allow for that to happen till 1733). In the meantime, he was earning his living by teaching. In 1732, he convinced the playwright Simon-Joseph Pellegrin to create a libretto for him. Based on Racine’s Phèdre, it was called Hippolyte et Aricie. The opera premiered on October 1st of 1733 in the theatre of Palais-Royal. André Campra, a major opera composer of the time, said, upon listening to Hippolyte: “There is enough music in this opera to make ten of them; this man will eclipse us all.” At the time, Rameau was 50 and at the beginning of his real career, as a tremendously productive opera composer. Working almost exclusively in that genre, he wrote 32 operas. One of the most successful was Dardanus, but not till Rameau rewrote almost half of it: the first edition was premiered in 1739 and was criticized for a weak libretto; the second, the one that is being staged these days, was created five years later, in 1744. Here’s a suite based on Dardanus. Tafelmusic orchestra is conducted by Jeanne Lamon. And here, to give the impression of the vocal part, is the aria Lieux funestes from the 4th act of the opera. The Scottish tenor Paul Agnew is Dardanus; Antony Walker conducts the Orchestra of the Antipodes.

Even though we have little space left, we can’t not mention Dmitry Shostakovich. In his symphonies, Shostakovich felt obligated to toe the line of Socialist Realism; with his phenomenal ear, he picked up the style and the melodies that, he hoped, would embody Soviet realities and please the Party cultural inquisitors. In most cases it worked, in some he was severely criticized. The smaller form, quartets, for example, were not so visible, and here Shostakovich could allow himself to be less political. Here’s one, Quartet no. 3 in F Major, op. 73. It’s performed by the Fitzwilliam String Quartet.Permalink

September 18, 2017. Čiurlionis. Here’s a composer whom we’ve managed to overlook all these years: Mikalojus Čiurlionis. He’s celebrated in Lithuania the way Smetana and Dvořák are celebrated in the Czech Republic – as a national composer. But he was more than that, he was also a very interesting painter. Čiurlionis was born onSeptember 22nd of 1875 in the south of Lithuania, in a village of Senoji Varėna which was then part of the Russian Empire. Though Lithuanian by nationality, the family’s language was Polish, as was customary with the educated Lithuanians of that time (the upper-class Russians used to speak better French than Russian). The triad of cultures, Lithuanian, Polish and Russian was to influence Čiurlionis’s life and creative development. When Mikalojus was two, the family moved to Druskininkai, a pretty spa town on the river Neman. There his father worked as a church organist. Musically talented, Mikalojus started playing piano by ear at the age of four and could fluently read music at seven. In 1889, he was sent to a music school in the town of Plungė. The school was established by Prince Michał Ogiński, a Polish nobleman and diplomat, who served as a Senator to Czar Alexander I of Russia. Ogiński was also an amateur composer, the author of the so-called Oginski Polonaise, very popular in Russian and Poland. On a scholarship Mikalojus was sent to the Warsaw Conservatory, where he studied for five years, from 1894 to 1899. Čiurlionis started seriously composing around 1900. He briefly studied at the Leipzig Conservatory, but by 1902 was back in Warsaw. It was there that he started painting and two years later entered the newly-established Warsaw School of Fine Arts.

with the educated Lithuanians of that time (the upper-class Russians used to speak better French than Russian). The triad of cultures, Lithuanian, Polish and Russian was to influence Čiurlionis’s life and creative development. When Mikalojus was two, the family moved to Druskininkai, a pretty spa town on the river Neman. There his father worked as a church organist. Musically talented, Mikalojus started playing piano by ear at the age of four and could fluently read music at seven. In 1889, he was sent to a music school in the town of Plungė. The school was established by Prince Michał Ogiński, a Polish nobleman and diplomat, who served as a Senator to Czar Alexander I of Russia. Ogiński was also an amateur composer, the author of the so-called Oginski Polonaise, very popular in Russian and Poland. On a scholarship Mikalojus was sent to the Warsaw Conservatory, where he studied for five years, from 1894 to 1899. Čiurlionis started seriously composing around 1900. He briefly studied at the Leipzig Conservatory, but by 1902 was back in Warsaw. It was there that he started painting and two years later entered the newly-established Warsaw School of Fine Arts.

In 1905, he traveled to the Caucuses and was enthralled by the landscape and the local. 1905 was the year of the Revolution in Russia. Even though in the end it didn’t amount to much, it stirred up national movements in countries on the periphery of the Russian Empire. Čiurlionis returned to Lithuania in 1907, settled in Vilnius and became very active in the arts movement, both visual and musical. He organized the first Lithuanian Arts exhibition, and also became very interested in Lithuanian songs and folk music, like Bartók and Kodály in Hungary. Till that time his knowledge of the Lithuanian language was limited, Polish being his native tongue, but he met a young woman, Sofija Kymantaitė, who agreed to teach him_-_1905.jpg) Lithuanian. Soon she became his wife. This was a time of great creative activity, as he was painting and composing music at a great pace. In 1908 Čiurlionis went to St. Petersburg, where he became involved with the painters of the Mir Iskusstva. His music was performed in the leading salons of the Russian capital, while his art was displayed by the Union of Russian Artists. Unfortunately, by the end of 1909, even as his career was on an upswing and he was feted by the major artists and musicians, he descended into a severe depression. He returned to Druskininkai and then was moved to a sanatorium outside of Warsaw. In April of 1911, while there, he caught a cold, developed pneumonia and died on April 10th. He was 35.

Lithuanian. Soon she became his wife. This was a time of great creative activity, as he was painting and composing music at a great pace. In 1908 Čiurlionis went to St. Petersburg, where he became involved with the painters of the Mir Iskusstva. His music was performed in the leading salons of the Russian capital, while his art was displayed by the Union of Russian Artists. Unfortunately, by the end of 1909, even as his career was on an upswing and he was feted by the major artists and musicians, he descended into a severe depression. He returned to Druskininkai and then was moved to a sanatorium outside of Warsaw. In April of 1911, while there, he caught a cold, developed pneumonia and died on April 10th. He was 35.

Here’s Čiurlionis’s early big symphonic work, In the Forest, written in 1900. Vladimir Fedoseyev conducts the Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra. The paining above is the tenth in his series, Creation of the World.Permalink

September 11, 2017. Hanslick. Last week when we wrote about Bruckner, we mentioned the name of Eduard Hanslick, a Viennese music critic and Bruckner’s detractor. It so happens that today is Hanslick’s birthday: he was born on September 11th of 1825. We usually write about major composers, but Hanslick was so influential as a music critic that his impact on the development and public perception of music can be compared to that of a major composer’s. Hanslick was born in Prague, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, into a German-speaking family. His father was a small and rather poor landowner; his mother was Jewish, the daughter of a well-to-do merchant; she converted to Catholicism upon marrying Hanslick senior. Richard Wagner, who would become Hanslick’s nemesis, never forgot that by blood Hanslick was half-Jewish. In Prague, Hanslick studied music with Václav Tomášek, a noted composer and teacher. He didn’t pursue his music studies but went to the University of Vienna, graduating with a degree in law. Still, music was his love; even while at the university he continued studying it and writing an occasional review. While working in different ministries, Hanslick continued writing musical criticism, first for Wiener Zeiting, the oldest newspaper in the world that is still published today, and then for another major newspaper, Die Presse, which is also still in publication. When in 1864 two former editors of Die Presse started a new newspaper, Neue freie Presse, Hanslick joined them as a music critic and remained there for the rest of his career. In 1854, Hanslick wrote a book, On the Beautiful in Music, one of the arguments of which was that “Music means itself,” that it has no “subject” and is not an expression of feelings. Unfortunately, this rather conventional notion contradicted Wagner’s ideas. Just three years earlier, Wagner had published an essay, Opera and Drama, in which he, while describing “music drama” as the synthesis of music, poetry and spectacle, also maintained that his music expresses the feelings intrinsic to poetry and drama. This made “esthetic of feelings” quite popular in the German-speaking world, and Hanslick’s refutation created a torrent of responses, both positive and negative. The book earned Hanslick a position of professor of “History and esthetics of music” at the University of Vienna, the first such position at any European university. On the other hand, Wagner took umbrage and, in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, created a character of Beckmesser, a town clerk and singer, who maliciously judges Walther’s performance, as a caricature on Hanslick. And in his essay, “Judaism in Music,” Wagner declared that Hanslick’s “Jewish style” of criticism is anti-German.

major composers, but Hanslick was so influential as a music critic that his impact on the development and public perception of music can be compared to that of a major composer’s. Hanslick was born in Prague, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, into a German-speaking family. His father was a small and rather poor landowner; his mother was Jewish, the daughter of a well-to-do merchant; she converted to Catholicism upon marrying Hanslick senior. Richard Wagner, who would become Hanslick’s nemesis, never forgot that by blood Hanslick was half-Jewish. In Prague, Hanslick studied music with Václav Tomášek, a noted composer and teacher. He didn’t pursue his music studies but went to the University of Vienna, graduating with a degree in law. Still, music was his love; even while at the university he continued studying it and writing an occasional review. While working in different ministries, Hanslick continued writing musical criticism, first for Wiener Zeiting, the oldest newspaper in the world that is still published today, and then for another major newspaper, Die Presse, which is also still in publication. When in 1864 two former editors of Die Presse started a new newspaper, Neue freie Presse, Hanslick joined them as a music critic and remained there for the rest of his career. In 1854, Hanslick wrote a book, On the Beautiful in Music, one of the arguments of which was that “Music means itself,” that it has no “subject” and is not an expression of feelings. Unfortunately, this rather conventional notion contradicted Wagner’s ideas. Just three years earlier, Wagner had published an essay, Opera and Drama, in which he, while describing “music drama” as the synthesis of music, poetry and spectacle, also maintained that his music expresses the feelings intrinsic to poetry and drama. This made “esthetic of feelings” quite popular in the German-speaking world, and Hanslick’s refutation created a torrent of responses, both positive and negative. The book earned Hanslick a position of professor of “History and esthetics of music” at the University of Vienna, the first such position at any European university. On the other hand, Wagner took umbrage and, in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, created a character of Beckmesser, a town clerk and singer, who maliciously judges Walther’s performance, as a caricature on Hanslick. And in his essay, “Judaism in Music,” Wagner declared that Hanslick’s “Jewish style” of criticism is anti-German.

While writing for Neue freie Presse, Hanslick became the leading music critic of Vienna, which itself was the foremost music center of Europe. He had rather conservative taste and wasn’t interested in music before Mozart. He felt that Beethoven had reached the pinnacle and that Schumann and Brahms were the main talents to follow him. Brahms became a close friend and Hanslick his major supporter and promoter. Hanslick tried to be objective toward Wagner’s music. He openly admired his virtuoso orchestration; he liked Tannhäuser and, surprisingly, Meistersinger, despite the “Beckmesser affair.” At the same time, he felt that the whole concept of “music drama” is detrimental to music development. Hanslick could be very cutting: “The Prelude to Tristan and Isolde reminds me of the old Italian painting of a martyr whose intestines are slowly unwound from his body on a reel.” Hanslick was also very negative toward Liszt and Bruckner, one composer who needed a lot of encouragement. These days Hanslick is remembered as a conservative who completely misunderstood the “new music” of Wagner and his followers. This is true, but we also should remember that he disliked some nativist, irrational aspects of Wagner’s (and Bruckner’s) music which the Nazis some decades later found so attractive.Permalink

September 4, 2017. Bruckner, Milhaud and more. Today is Labor Day, so we’ll be very brief. Anton Bruckner was born on this day in 1824. Nine years older than Brahms, another great symphonist, today his music sounds more daring. Bruckner had many supporters and several powerful detractors, the most influential being Eduard Hanslick, the Viennese music critic who wrote devastating reviews. Here’s one quote from his article about Bruckner’s Third Symphony: "Neither were his [Bruckner's] poetic intentions clear to us – perhaps a vision of how Beethoven's Ninth made friends with Wagner's Valkyries and ended up under horse’s hooves – nor could we grasp the purely musical coherence." These reviews were especially painful to Bruickner as he was an unusually insecure composer. All of Bruckner’s symphonies are large in scale, and so are the three masses (Bruckner was a deeply religious person and church music played a very important part in his compositional output). His motets, though, are much smaller and are a better fit for this post. Here’s one, Os Justi Meditabitur (The mouth of the righteous utters wisdom). The Monteverdi Choir is conducted by John Eliot Gardiner.

another great symphonist, today his music sounds more daring. Bruckner had many supporters and several powerful detractors, the most influential being Eduard Hanslick, the Viennese music critic who wrote devastating reviews. Here’s one quote from his article about Bruckner’s Third Symphony: "Neither were his [Bruckner's] poetic intentions clear to us – perhaps a vision of how Beethoven's Ninth made friends with Wagner's Valkyries and ended up under horse’s hooves – nor could we grasp the purely musical coherence." These reviews were especially painful to Bruickner as he was an unusually insecure composer. All of Bruckner’s symphonies are large in scale, and so are the three masses (Bruckner was a deeply religious person and church music played a very important part in his compositional output). His motets, though, are much smaller and are a better fit for this post. Here’s one, Os Justi Meditabitur (The mouth of the righteous utters wisdom). The Monteverdi Choir is conducted by John Eliot Gardiner.

Darius Milhaud, a member of Les Six, was also born on this day, in 1892 in Aix-en-Provence into a Jewish family. He traveled extensively, absorbing influences from other cultures. In 1917, he went to Brazil and found inspiration in the local folk music and traditions of the Carnaval. In 1922, he traveled to the United States where for the first time he encountered authentic jazz, which made a huge impression on him. In 1940, after the Germans occupied part of France, Milhaud fled to the US. There he found a position at Mills College in Oakland, CA. One of his favorite students was Dave Brubeck. Here is Milhaud’s whimsical Ballade for Piano and Orchestra, op.61. Vlastimil Lejsek is on the Piano. Brno Philharmonic Orchestra is conducted by Jiří Waldhans.

Johann Christian Bach, Giacomo Meyerbeer, Amy Beach and John Cage were all born this week. We’ll be less perfunctory the next time.Permalink