Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

February 12, 2018. Four solid talents. Three early-music composers were born this week: Francesco Cavalli, one of the pioneers of opera, on February 14th of 1602; Michael Praetorius, an immensely prolific German composer of the Protestant church music, most likely on February 15th of 1571; and Arcangelo Corelli, on February 17th of 1653. It so happens that we wrote about all three of them last year. Four lesser composer were also born this week -- Fernando Sor, Alexander Dargomyzhsky, Georges Auric and Henri Vieuxtemps. Fernando Sor, a Catalan guitarist and composer, was born on February 13th of 1778 in Barcelona. He moved around Europe quite a bit, first living in Paris, then in London, and then moving to Moscow, where he stayed for four years. He returned to Paris and lived there for the rest of his life (he died in 1839). Sor was considered the foremost guitar virtuoso of his time; even though he wrote music in many genres, he is known today for his guitar compositions. Here’s one of his most popular pieces, Variations on a Theme by Mozart. It’s performed by the Spanish guitarist Rafael Serrallet.

Alexander Dargomyzhsky, born on February 14th of 1813, was an interesting Russian composer who lived in the period between Mikhail Glinka and the generation of the Mighty Five. Dargomyzhsky met Glinka at the age of 22; they became friends, played piano four hands and studied scores together. Encouraged by Glinka, he wrote an opera, Esmeralda, which had to wait its premier for eight years and then disappeared from the stage. Disappointed, Dargomyzhsky went to Europe – Brussels, Berlin, Paris, Vienna – where he met many major composers and musicians. After two years of travels he returned to Russia to start working on the opera Rusalka. That one also had to wait – it was premiered only in 1856. His best-known opera, The Stone Guest, was left unfinished; it was completed by César Cui and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Dargomyzhsky wrote a number of lovely songs; here’s one of them, Molitva (The prayer) and here’s another, V tverdi nebesnoy (In heavenly firmament). Both are sung by the soprano Galina Vishnevskaya, accompanied on the piano by her famous husband, the cellist Mstislav Rostropovich. The recording was made in 1991 when Vishnevskaya was 65 and beyond her prime. Even if her voice isn’t as solid as it was at her prime, the phrasing is beautiful.

friends, played piano four hands and studied scores together. Encouraged by Glinka, he wrote an opera, Esmeralda, which had to wait its premier for eight years and then disappeared from the stage. Disappointed, Dargomyzhsky went to Europe – Brussels, Berlin, Paris, Vienna – where he met many major composers and musicians. After two years of travels he returned to Russia to start working on the opera Rusalka. That one also had to wait – it was premiered only in 1856. His best-known opera, The Stone Guest, was left unfinished; it was completed by César Cui and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Dargomyzhsky wrote a number of lovely songs; here’s one of them, Molitva (The prayer) and here’s another, V tverdi nebesnoy (In heavenly firmament). Both are sung by the soprano Galina Vishnevskaya, accompanied on the piano by her famous husband, the cellist Mstislav Rostropovich. The recording was made in 1991 when Vishnevskaya was 65 and beyond her prime. Even if her voice isn’t as solid as it was at her prime, the phrasing is beautiful.

Two Francophone composers were also born this week, Henri Vieuxtemps and Georges Auric: Vieuxtemp, a Belgian, on February 17th of 1820 and Auric, a Frenchman, on February 15th of 1899. Vieuxtemp was one of the best violinists of his time; Robert Schumann, who met him when 13-year-old Vieuxtemp toured Germany, compared him to Paganini (Paganini himself was impressed with the young virtuoso). Vieuxtemp spent five years in Russia at the court of Nicolas I and practically laid the foundation of the Russian school of violin playing. He composed seven violin concertos; here is the first movement, Allegro non troppo. of his concerto no. 5. In this 1961 recording, Jascha Heifetz is playing with the New Symphony Orchestra of London, Malcom Sargent conducting.

Georges Auricwas one of the Les Six. He was born in Lodève, in the south of France. He collaborated with Jean Cocteau for many years, writing music to Cocteau’s ballet librettos and films. Here’s his fun Trio for oboe, clarinet and bassoon, performed by the Arundo-Donax Ensemble.Permalink

February 5, 2018. Berg and two pianists. Alban Berg, one of the most influential composers of the 20th century, was born on February 9th of 1885. A year ago, we posted a detailed entry about him, so this time we’ll just play some of his music. Berg wrote the Lyric Suite in 1925/26 using the 12-tone technique following his teacher, Arnold Schoenberg’s theories, and dedicated it to Alexander von Zemlinsky. Here is the first movement of the Suite, Allegretto gioviale, and here – the second, Andante amoroso, lyrical indeed, despite its 12-tone origin. They are performed by the Alban Berg Quartett.

technique following his teacher, Arnold Schoenberg’s theories, and dedicated it to Alexander von Zemlinsky. Here is the first movement of the Suite, Allegretto gioviale, and here – the second, Andante amoroso, lyrical indeed, despite its 12-tone origin. They are performed by the Alban Berg Quartett.

As no other significant composers were born this week (unless you’re fond of the music of Gretry), we’ll turn to the instrumentalists. A week ago was the birthday of Arthur Rubinstein, one of the greatest pianists of the 20th century. Rubinstein life is legendary, both musically and socially; he dominated the music scene for more than 80 years. A small blurb would never do it justice, so we’ll have to start today and continue at a later date. Rubinstein was born on January 28th of 1887 in Łódź, in the part of Poland that back then belonged to the Russian Empire. His Jewish parents owned a small textile factory. Rubinstein was a child prodigy if ever there was one: at the age of three he was taken to Berlin to play for Joseph Joachim, the famous violinist and Brahms’s collaborator, who listen to him and declared that the boy may become a great musician. He played his first concert in Łódź at the age of seven, and made his Berlin debut in 1900, playing Mozart’s Piano concerto no. 23, Saint-Saëns’s Piano concerto no. 2 and pieces by Schumann and Chopin (Joahim conducted the orchestra). He started playing regular concerts in Poland and Germany, and in 1904 moved to Paris. There, he became friends with many musicians: the violinist Jacques Thibaud, composers Maurice Ravel, Paul Dukas and another Pole, Karol Szymanowski. Two years later, in 1906, he made his American debut at the Carnegie Hall, playing with the Philadelphia orchestra. (He would play his last Carnegie Hall concert 70 years later, at the age of 89). At that time, Rubinstein was leading a very active social life, he was spending much time chasing women (although some would say that they were chasing him) and not studying enough. He didn’t have a regular piano teacher; many of his concerts were carried by his natural talent and enthusiasm but were under-prepared. The New York critics noticed it and his Carnegie Hall debut received rather mixed reviews. By 1908 he was back in Berlin having big financial problems and desperate. He even attempted suicide, half-heartedly it seems. That was a cathartic event, as he was, in his own words, “reborn.” In 1912 Rubinstein made his London debut and settled in Chelsey. He became friends with two American expats, Muriel and Paul Draper, whose Chelsea salon was a center of London music life. There he met Igor Stravinsky, Pierre Monteux, Pablo Casals and many other musicians. He stayed in London during the Great War; very much anti-German by then, he played his last concert in Germany in 1914.

Rubinstein had a very large repertoire and is known as probably the best interpreter ever of the music of Chopin. It’s a revelation to listen to his interpretations of the same piece recorded during the different phases of his career. Here’s Chopin’s Nocturne Op.9 No.2 in it’s perfect simplicity. The recording was made in 1965, when Rubinstein was 78.

Another pianist was born this week and we’d like to at least mention him (we’ll write about him at another date). Claudio Arrau, also one of the greatest, was born in Chillán, Chile, on February 6th of 1903.Permalink

January 29, 2018. From Palestrina to Nono. This week covers an incredible 450 year span of European classical music, from Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, whose first compositions were published in 1554 to Luigi Nono, who died in 1990 and composed till his very last years. Franz Schubert and Felix Mendelssohn were also born this week, Schubert on January 31st of 1797, and Mendelssohn – on February 3rd of 1809. We’ve written about both many times and of course will come back to them in the future.

We celebrate Palestrina this week even though we don’t know for sure what year he was born: letters and records from Palestrina’s life suggest that he was born sometime between February 3, 1525 and February 2, 1526 but these February dates provide us with a good excuse to commemorate the great Italian composer this week. Palestrina’s life is rather well documented; we know that he started his training at the great basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, that he was later appointed to the Capella Giulia at Saint Peter and sometime later to the more prestigious Cappella Sistina. In 1561 he succeeded Orlando di Lasso as maestro di cappella at San Giovanni in Laterano. Funds were lacking, and the capella never reached the level sought by Palestrina; in 1566 he quit. After serving for several years at his alma mater, Santa Maria Maggiore, and then, for a brief period, at the employ of Cardinal Ipolitto d’Este, at the Villa d’Este in Tivoli, he eventually returned to the Vatican’s Capella Giulia and stayed there till the end of his life. His fame grew across Italy and Europe; he was considered “the very first musician in the world” by a person close to Alfonso II d'Este - the Duke of Ferrara, who would know, since theDuke’s court was a major center of cultural life of Italy. Palestrina died in 1594 in Rome. He was widely published during his lifetime and admired by the popes for whom he worked, and other patrons of art: Philipp II of Spain, the Gonzagas and d’Este. Palestrina left a huge legacy: 104 masses, more than 300 motets, 140 secular madrigals and more. We have several of his works in our library but here’s other example, a motet Dies sanctificatus.

letters and records from Palestrina’s life suggest that he was born sometime between February 3, 1525 and February 2, 1526 but these February dates provide us with a good excuse to commemorate the great Italian composer this week. Palestrina’s life is rather well documented; we know that he started his training at the great basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, that he was later appointed to the Capella Giulia at Saint Peter and sometime later to the more prestigious Cappella Sistina. In 1561 he succeeded Orlando di Lasso as maestro di cappella at San Giovanni in Laterano. Funds were lacking, and the capella never reached the level sought by Palestrina; in 1566 he quit. After serving for several years at his alma mater, Santa Maria Maggiore, and then, for a brief period, at the employ of Cardinal Ipolitto d’Este, at the Villa d’Este in Tivoli, he eventually returned to the Vatican’s Capella Giulia and stayed there till the end of his life. His fame grew across Italy and Europe; he was considered “the very first musician in the world” by a person close to Alfonso II d'Este - the Duke of Ferrara, who would know, since theDuke’s court was a major center of cultural life of Italy. Palestrina died in 1594 in Rome. He was widely published during his lifetime and admired by the popes for whom he worked, and other patrons of art: Philipp II of Spain, the Gonzagas and d’Este. Palestrina left a huge legacy: 104 masses, more than 300 motets, 140 secular madrigals and more. We have several of his works in our library but here’s other example, a motet Dies sanctificatus.

Almost half a millennium later, another Italian became famous as one of the most forward-looking composers of his generation. Luigi Nono’s music may sound as difficult as some of Palestrina’s masses, our ear being so used to the melodic tonality of the intervening centuries, but most music lovers would agree that it’s very interesting. Nono was born in Venice on January 29th of 1924. At the Venice Conservatory he studied with the noted composer Gian Francesco Malipiero. After graduation, Nono became friends with Bruno Maderna, a leading modernist composer of his generation. In 1950, Nono’s work, a 12-tone piece, was presented in Darmstadt, the mecca of the avant-garde. Soon after, Nono became a leading figure at Darmstadt, together with Maderna, Stockhausen and Boulez. It’s interesting to note that composers of both the 16th and the 20th century struggled with almost identical problems. In the 16th, the Catholic church was on the verge of banning polyphony masses because Cardinals deemed they made sacred texts incomprehensible. It’s thought that Palestrina "saved" the polyphony with his Missa Papae Marcelli, which demonstrated that a mass can be both, polyphonic and understandable. In the 20th century, Luigi Nono was accused by Stockhausen of the same - that words in Nono’s piece (Stockhausen was talking about Il canto sospeso) were impossible to understand, which, in Stockhausen’s opinion, made the whole idea of using texts absurd. That was a serious accusation, as Nono selected the texts from a poignant collection of arewell letters that captured Resistance fighters wrote before being executed by the Nazis. Nono strenuously objected but it seems Stockhausen was correct. You can judge for yourself. Il canto sospeso is a difficult piece but worth the effort. It’s here, SWR Symphonieorchester is conducted by Peter Rundel.Permalink

January 22, 2018. Mozart in Vienna, early years. s birthday is this week – he was born on January 27th in 1756. Last year we wrote about his life and music during the period around 1781, when the 25-year-old Mozart finally left Salzburg and settled in Vienna. He first stayed at Singerstrasse 7, not far from Stephansplatz. Later in 1781 he moved in with the family of the Webers. Mozart met the Webers in 1777, while they still lived in Mannheim. The Webers had four daughters, Aloysia, Josepha, Constanze and Sofie. Both Aloysia and Josepha were fine singers; some years later Josepha would premier the role of the Queen of Night in The Magic Flute. Mozart promptly fell in love with Aloysia, but had to leave Mannheim after a short stay as his father Leopold wanted him to go to Paris. Several months later Mozart met Aloysia again, this time in Munich, where she was singing at the Court Theater. Unfortunately, by then Aloysia’s feeling had changed, she even pretended not to recognize Mozart. According to Georg Nikolaus von Nissen, Mozart’s biographer and the husband of Mozart’s widow, Constanze, Mozart’s reaction was swift: he sat at the piano and sung, “The one who doesn’t want me could kiss my ass” (Mozart wasn’t shy of using scatological terms).

1781, when the 25-year-old Mozart finally left Salzburg and settled in Vienna. He first stayed at Singerstrasse 7, not far from Stephansplatz. Later in 1781 he moved in with the family of the Webers. Mozart met the Webers in 1777, while they still lived in Mannheim. The Webers had four daughters, Aloysia, Josepha, Constanze and Sofie. Both Aloysia and Josepha were fine singers; some years later Josepha would premier the role of the Queen of Night in The Magic Flute. Mozart promptly fell in love with Aloysia, but had to leave Mannheim after a short stay as his father Leopold wanted him to go to Paris. Several months later Mozart met Aloysia again, this time in Munich, where she was singing at the Court Theater. Unfortunately, by then Aloysia’s feeling had changed, she even pretended not to recognize Mozart. According to Georg Nikolaus von Nissen, Mozart’s biographer and the husband of Mozart’s widow, Constanze, Mozart’s reaction was swift: he sat at the piano and sung, “The one who doesn’t want me could kiss my ass” (Mozart wasn’t shy of using scatological terms).

While living with the Webers in Vienna, Mozart fell in love with Constanze, the third daughter. They married on August 4th of 1782 (papa Leopold consented to the marriage only grudgingly). In the following years, till his death in 1791, he and Constanza moved a dozen times but all of their addresses were within the city’s central First District. The first pieces composed in Vienna were several sonatas for keyboard and violin, K 376 through K 380. The set was dedicated to Josepha Auernhammer, then 23, a pianist and Mozart’s pupil. Josepha fell in love with her teacher; at that time Mozart was still courting Constanza but there was a period in 1782 when they separated; it’s possible that Mozart’s affair with Josepha took place during that period. Here is the Violin sonata K 380, performed by Henryk Szeryng, violin, and Ingrid Haebler, piano. Mozart also wrote a lovely sonata for two pianos to be played by him and Josepha. It’s performed here by two young American pianists, Nimrod David Pfeffer and Rafael Skorka. But the main composition of Mozart’s first year in Vienna was the opera Die Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Seraglio). It premiered on July 16th, 1782 in the Vienna Burgtheater to huge success. In addition to the Burgtheater, the opera was staged by Emanuel Schikaneder, a librettist (he wrote the libretto to the Magic Flute), composer and impresario, who founded the Theater an der Wien. Even during Mozart’s time, productions of the opera were staged throughout German-speaking cities. Here’s Belmonte’s aria Konstanze, dich wiederzusehen! ... O wie ängstlich, o wie feurig!, a favorite not just with the public but with Mozart himself. In this 1965 recording the superb Fritz Wunderlich is Belmonte.Permalink

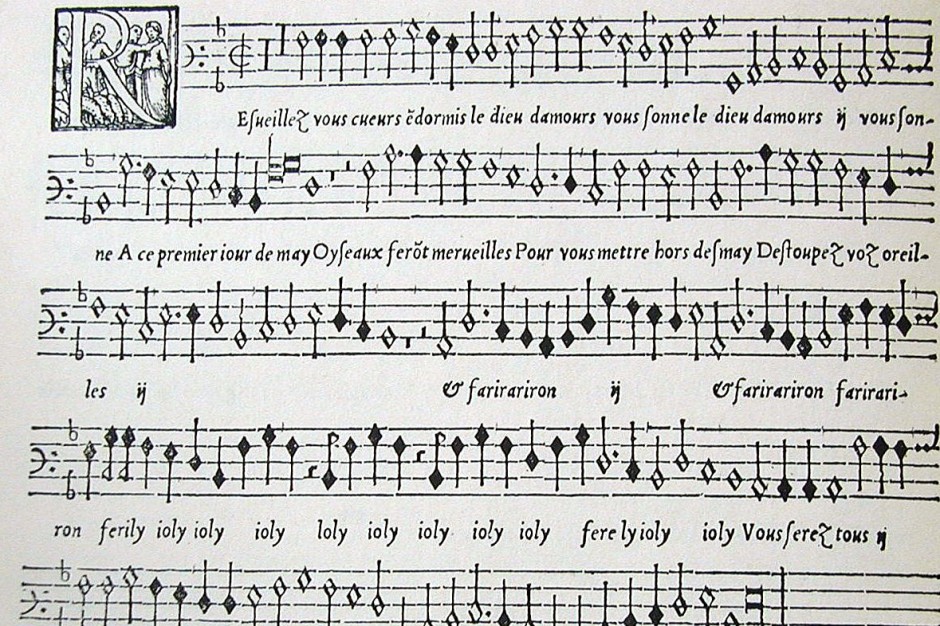

January 15, 2018. Nicolas Gombert. We have never written about Nicolas Gombert, which is quite an omission, considering that Gombert is considered to be one of the greatest Flemish composers of the generation following Josquin des Prez. Gombert was born around 1495 in southern Flanders. Some musicologists speculate that he studied with Josquin, who at that time was living in Condé-sur-l'Escaut, not far from Gombert’s presumed birthplace. Even if he wasn’t Josquin’s student, Gombert was clearly an admirer, as he wrote music to commemorate Josquin’s death. Sometime around 1526 Gombert found employment with the court of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. Charles’s lands stretched from the Netherlands and Flanders to Spain, Austria, some German states and Italy, and he traveled extensively. Gombert accompanied the emperor on his trips, being “Master of the boys” of the court chapel. As he visited different countries, his fame grew, with his music being published in many countries. Even though he was never formally appointed maître de chapelle (music director) of the court, he served as court composer. Gombert’s life changed dramatically in 1540. According to Gerolamo Cardano, a court physician, he committed a “gross indecency” against a boy in the emperor’s employ. Gombert was sentenced to the galleys and spent several years in the high seas. We don’t know how long his punishment lasted and what his conditions were like, but during that time he managed to compose several pieces. Those found their way back to the court and eventually earned Gombert the emperor’s pardon. It seems that Gombert spent the last years of his in Tournai: in 1547 he sent a letter from there to Ferrante Gonzaga, Charles’s captain (Ferrante was known as a patron of composers – some years later he would bring two great composers to his court, Orlando di Lasso and Giaches de Wert). Gombert probably died in Tournai sometime around 1560.

of the generation following Josquin des Prez. Gombert was born around 1495 in southern Flanders. Some musicologists speculate that he studied with Josquin, who at that time was living in Condé-sur-l'Escaut, not far from Gombert’s presumed birthplace. Even if he wasn’t Josquin’s student, Gombert was clearly an admirer, as he wrote music to commemorate Josquin’s death. Sometime around 1526 Gombert found employment with the court of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. Charles’s lands stretched from the Netherlands and Flanders to Spain, Austria, some German states and Italy, and he traveled extensively. Gombert accompanied the emperor on his trips, being “Master of the boys” of the court chapel. As he visited different countries, his fame grew, with his music being published in many countries. Even though he was never formally appointed maître de chapelle (music director) of the court, he served as court composer. Gombert’s life changed dramatically in 1540. According to Gerolamo Cardano, a court physician, he committed a “gross indecency” against a boy in the emperor’s employ. Gombert was sentenced to the galleys and spent several years in the high seas. We don’t know how long his punishment lasted and what his conditions were like, but during that time he managed to compose several pieces. Those found their way back to the court and eventually earned Gombert the emperor’s pardon. It seems that Gombert spent the last years of his in Tournai: in 1547 he sent a letter from there to Ferrante Gonzaga, Charles’s captain (Ferrante was known as a patron of composers – some years later he would bring two great composers to his court, Orlando di Lasso and Giaches de Wert). Gombert probably died in Tournai sometime around 1560.

Gombert is considered one of the last Franco-Flemish composers who still worked outside of Italy. Gombert’s contemporary, Adrian Willaert, would move to Italy, and so would Orlando and practically all other significant Flemish composers. Gombert was considered a master of polyphony, and you can hear it in our samples. Here’s his motet In te Domine speravi. Paul Van Nevel conducts the Huelgas ensemble. And here – the Magnificat secundi toni, performed by the same artists.Permalink

Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli was born in Brescia, northern Italy. Though he started studying the violin (at the age of three), he switched to the piano soon after. He was accepted at the Milan Conservatory at ten and graduated at the age of 14. He was not very successful at the Ysaÿe International Festival in 1938, where he took 7th place (Emil Gilels was the winner) but a year later he won the Geneva Piano competition. There, the perfection of his playing already apparent, and he was called “the new Liszt.” In 1940 he played a sensational debut concert in Rome. During WWII he served in the Italian air force but resumed his career soon after the war’s end. He debuted in London in 1946 and in the US – in 1948. In the 1950s he stopped concertizing for a while, concentrating on teaching, and formed his own International Pianists’ Academy. Maurizio Pollini and Martha Argerich were his students. Michelangeli resumed playing concerts in 1960, even though he was known to cancel almost as many concerts as he played. Michelangeli’s repertoire was very small for a pianist of his standing, especially compared to pianists like Sviatoslav Richter, but the crystalline perfection of his playing was incomparable. Michelangeli died in Lugano on June 12th of 1995. Here’s Chopin’s Ballade no. 1 in his 1972 recording.

Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli was born in Brescia, northern Italy. Though he started studying the violin (at the age of three), he switched to the piano soon after. He was accepted at the Milan Conservatory at ten and graduated at the age of 14. He was not very successful at the Ysaÿe International Festival in 1938, where he took 7th place (Emil Gilels was the winner) but a year later he won the Geneva Piano competition. There, the perfection of his playing already apparent, and he was called “the new Liszt.” In 1940 he played a sensational debut concert in Rome. During WWII he served in the Italian air force but resumed his career soon after the war’s end. He debuted in London in 1946 and in the US – in 1948. In the 1950s he stopped concertizing for a while, concentrating on teaching, and formed his own International Pianists’ Academy. Maurizio Pollini and Martha Argerich were his students. Michelangeli resumed playing concerts in 1960, even though he was known to cancel almost as many concerts as he played. Michelangeli’s repertoire was very small for a pianist of his standing, especially compared to pianists like Sviatoslav Richter, but the crystalline perfection of his playing was incomparable. Michelangeli died in Lugano on June 12th of 1995. Here’s Chopin’s Ballade no. 1 in his 1972 recording.

January 8, 2017. Three pianists. Three great pianists of the last century were born last week, and by remarkable coincidence all three were born on the same day, January 5th: Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli in 1920, Alfred Brendel in 1931, and Maurizio Pollini – in 1942. So very different as performers (even their repertoires have little in common), all three were cerebral musicians who did not wear their hearts on the sleeve. Their playing is faithful to the score and emotions come from the composer, not the artifice.

The great Austrian pianist Alfred Brendel was born in Wiesenberg in what is now the Czech Republic. His family moved to Zagreb when Alfred was six, and then to Graz, Austria, where he studied at the local conservatory. What is quite unusual for a future virtuoso is that Brendel didn’t have formal piano classes past the age of 14 and was mostly self-taught. Neither did he have a brilliant competition career: he only participated in one, the Buzoni, and took the fourth prize. His career was built slowly, as he played concerts across Europe. His made several recordings, again starting with just a few (later he would record all of Beethoven sonatas three times, and also three times all of Beethoven concertos – with James Levine and the Chicago Symphony, with Simon Rattle and the Vienna Philharmonic, and with Bernard Haitink and London Philharmonic. He also recorded all Mozart piano pieces and most of Schubert). The breakthrough came after his London concert in the late 1960s: it was taped, and the recording companies came calling. In 1972, after living in Vienna for 20 years, Brendel moved to London; he still lives there. Brendel is a supreme interpreter of the music of Schubert, Beethoven, and late Liszt. Here’s Brendel playing Schubert Impromptu Op.90 No.1

Compared to Brendel’s, Maurizio Pollini’s path to fame was more conventional. Born in Milan (he still lives there), he went to the local conservatory, and at the age of 18 won the International Chopin Piano competition. After a shaky couple of years Pollini embarked on a performance career. His technique, interpretive precision and depth brought him great acclaim. Pollini’s repertoire is broad and unusual. On the one hand, he’s one of the greatest Chopin players of the century. At the same time, his Beethoven is superb (not many pianists can play both at the same level). Pollini is also a great champion of contemporary music: in addition to Schoenberg and Webern he plays works of Pierre Boulez, Luigi Nono, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Bruno Maderna. Here’s Pollini’s interpretation of Chopin’s Nocturne No.1 Op.9 in B Flat minor.Permalink