Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

March 26, 2018. Richter and Haydn. Last week we started writing about the pianist Sviatoslav Richter, and made it all the way to 1941, when Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union. Richter, 26 years old, joined many other musicians who continued to perform during the war, often on the front line. In January 1943 he premiered Prokofiev’s Piano Sonata no. 7, one of the three so-called “War Sonatas” (sonatas sixth through eighth). Richter already new Prokofiev: they met over Prokofiev’s Sonata no. 6..jpg) Premiered by the composer, the sonata became part of Richter’s repertoire; he played it on his first “official” Moscow concert in 1940. And even though he didn’t premier Prokofiev’s Eighth (Emil Gilels did), he played it at the Third All-Union competition in 1945, which Richter won (Victor Merzhanov shared the first prize with him). Here’s a live recording of Prokofiev’s Piano Sonata no. 7 from 1958.

Premiered by the composer, the sonata became part of Richter’s repertoire; he played it on his first “official” Moscow concert in 1940. And even though he didn’t premier Prokofiev’s Eighth (Emil Gilels did), he played it at the Third All-Union competition in 1945, which Richter won (Victor Merzhanov shared the first prize with him). Here’s a live recording of Prokofiev’s Piano Sonata no. 7 from 1958.

In 1943 Richter met Nina Dorliak, a fine opera and chamber singer. Nina was born into a prominent family: her father was a deputy to the Czar’s finance minister; her mother in her youth was a lady-in-waiting to dowager Empress Maria, later she became a well-known singer herself. Considering such legacy, it’s a miracle that Nina was not arrested during the Great Purge. Dorliak and Richter became good friends and played many concerts together. In 1945 Richter, most likely a closeted homosexual (he never talked about it), proposed to Nina. They married in 1945 and stayed together to the end of his life.

After the war, Richter, by then one of the most popular young pianists, extensively toured the Soviet Union and the countries of the Eastern bloc, but not in the West. Part of the “problem” was his parents (his German father was executed at the beginning of the war, his mother moved to Germany), partly because of his connections to the artists out of favor with the State, such as Prokofiev, who, from 1948 on was repeatedly criticized as “formalist,” as well as the poet Boris Pasternak. All of this changed with Khrushchev’s “thaw,” when Richter was allowed to go on a tour of the US. He played his first American concert on October 15th of 1960 in Chicago (Brahms’s Second Piano Concerto with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Erich Leinsdorf). On October 19th he played a massive concert in Carnegie Hall: five Beethoven sonatas, including the Appassionata (no. 23); two Etudes from Chopin’s op. 10, a Schubert’s Impromptu (D 899, no. 4) and Robert Schumann’s Fantasiestücke, opus 12, no. 2. He played another concert several days later, this one consisting of Prokofiev’s piece: piano sonatas nos. 6 and 8, and smaller pieces. Two more concerts followed: Haydn's Sonata No. 50 in C Major, Schumann and Debussy in one, and Schumann, Chopin, Ravel and Scriabin in another. He continued the tour through the end of the year, visiting Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago again, and the West coast. In December he played Carnegie Hall two more times. Altogether, he played more than 60 different pieces, including five different piano concertos: Tchaikovsky’s First, Brahms’s Second, Beethoven’s First, Liszt’s Second, and Dvořák’s. It’s difficult to think of another pianist with such a breadth of repertoire.

Franz Joseph Haydn was born on March 31st of 1732. Richter played many of his pianos sonatas (and also the piano concerto). Here’s Haydn’s Piano Sonata in C major, Hob.XVI:35. It was recorded in 1967.Permalink

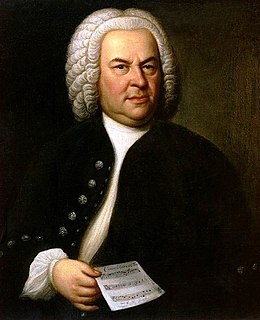

March 19, 2018. Bach and Richter. In two days we’ll celebrate Johann Sebastian Bach’s 333rd birthday. We’ve written about Bach’s early years in Leipzig (here and here), the years that were dedicated to his work as the Kantor at Tomasschule, the school of the St. Thomas church, wherehe also served as the choir director. All along Bach was the music director of two other important churches in the city, St. Nicholas church (Nikolaikirche) and Paulinerkirche, the University church. His duties included writing music for Sunday services, and in the early Leipzig years he produced an astonishing number of cantatas, more than 300 altogether, of which 200 plus are extant. He also wrote several Passions, of which the St. John’s and St. Matthew survive. By the year 1729 the accumulated volume of compositions was such that he could allow himself to either perform the old music, or reuse pre-existing material, creating what is called “parody” cantatas. (The old and rather unusual musical term “parody,” or imitation, has nothing to do with humor. “Parody mass,” for example, was one of the major types of Renaissance mass where the composer used – and acknowledged – the borrowed material. The intellectual property rules were very vague in those days). By the year 1729, Bach’s creative forces shifted away from church music to secular music. One impetus was Collegium Musicum, of which Bach was appointed the director in 1729. Collegium Musicum was created by Telemann in 1702 as an association of professional musicians and students for the purpose of producing regular public concerts. During the winter the concerts were given at Café Zimmermann, one of the largest coffee houses in Leipzig (the building was constructed in 1715; it was destroyed during the Allied air raid in 1943). Bach’s Coffee Cantata, BWV 211, was probably premiered at Zimmermann’s. Several of Bach’s keyboard and violin concertos were written for Collegium Musicum. It’s quite likely that Wilhelm Friedemann and Carl Philipp Emanuel, two of Bach’s sons, performed with the Collegium. Bach also continued writing keyboard pieces. Those were published in four books called Clavier-Übung, or keyboard exercise. The first volume, published in 1731, contained six partitas for harpsichord, the second, in 1735 – two pieces, the Italian Concerto BWV 971 and Overture in the French style, BWV 831. You can hear the Italian Concerto here, and the Overture – here. Both are performed by Sviatoslav Richter; the recordings were made in 1991, when Richter was 76.

important churches in the city, St. Nicholas church (Nikolaikirche) and Paulinerkirche, the University church. His duties included writing music for Sunday services, and in the early Leipzig years he produced an astonishing number of cantatas, more than 300 altogether, of which 200 plus are extant. He also wrote several Passions, of which the St. John’s and St. Matthew survive. By the year 1729 the accumulated volume of compositions was such that he could allow himself to either perform the old music, or reuse pre-existing material, creating what is called “parody” cantatas. (The old and rather unusual musical term “parody,” or imitation, has nothing to do with humor. “Parody mass,” for example, was one of the major types of Renaissance mass where the composer used – and acknowledged – the borrowed material. The intellectual property rules were very vague in those days). By the year 1729, Bach’s creative forces shifted away from church music to secular music. One impetus was Collegium Musicum, of which Bach was appointed the director in 1729. Collegium Musicum was created by Telemann in 1702 as an association of professional musicians and students for the purpose of producing regular public concerts. During the winter the concerts were given at Café Zimmermann, one of the largest coffee houses in Leipzig (the building was constructed in 1715; it was destroyed during the Allied air raid in 1943). Bach’s Coffee Cantata, BWV 211, was probably premiered at Zimmermann’s. Several of Bach’s keyboard and violin concertos were written for Collegium Musicum. It’s quite likely that Wilhelm Friedemann and Carl Philipp Emanuel, two of Bach’s sons, performed with the Collegium. Bach also continued writing keyboard pieces. Those were published in four books called Clavier-Übung, or keyboard exercise. The first volume, published in 1731, contained six partitas for harpsichord, the second, in 1735 – two pieces, the Italian Concerto BWV 971 and Overture in the French style, BWV 831. You can hear the Italian Concerto here, and the Overture – here. Both are performed by Sviatoslav Richter; the recordings were made in 1991, when Richter was 76.

One of the greatest pianists of the 20th century, Sviatoslav Richter was born on March 20th of 1915 in Zhitomir, Ukraine. His father, Teofil Richter, was a pianist and a German expat, his mother was Russian. The family moved to Odessa in 1921. Even though Teofil taught at the Conservatory, little Sviatoslav studied music mostly on his own. At the age of 15 he started working at the local opera as a rehearsal pianist. Without any further formal education, he auditioned for Heinrich Neuhaus at the Moscow Conservatory in 1937. Neuhaus, who had the strongest class in all of the Conservatory (Emil Gilels and Radu Lupu were his students), accepted him immediately. Richter’s studies didn’t last long, though: he wouldn’t attend the non-music classes, was kicked out after several months and returned to Odessa. Neuhaus, who considered his pupil a genius, insisted that he return. Richter was re-admitted but got his official diploma only in 1947. That didn’t stop him from playing concerts: in 1940 he premiered Prokofiev’s Sixth Piano sonata, then played his first Moscow concert with the orchestra. As Germany attacked Russia in 1941, Sviatoslav’s life, as that of every other Soviet citizen, changed forever. His father, as so many Russian Germans, was arrested and later executed. His mother disappeared and was presumed dead; only many years later would Sviatoslav find out that she eventually made it to Germany. To be continued next week. Permalink

March 12, 2018. Malipiero and more. Hugo Wolf, a tremendously talented Austrian composer who died tragically young in a syphilis-induced delirium, was born on March 13th of 1860. Last your we dedicated an entry to him, so here are two of his songs. First, Schlafendes Jesuskind (Sleeping Baby Jesus) from the cycle Mörike-Lieder is sung by the French baritone Gérard Souzay with Dalton Baldwin at the piano. Then, Nachtzaube (Night magic), from Eichendorff Lieder. It’s performed by Elisabeth Schwarzkopf and Gerald Moore.

Georg Philipp Telemann, born on March 14th of 1681 was, in many ways, Wolf’s direct opposite. He lived a long life (86 years), wrote an immense number of pieces (1700 cantatas, numerous oratorios, more than 50 operas and a large number of instrumental suites, concertos and sonatas). He was in good health for most of his life, had many children, and clearly didn’t suffer from depression, as Wolf did all his life. The challenge with Telemann is to find the great works (and he wrote some wonderful music) among his immense, and sometimes mediocre, output. La Changeante, Telemann’s Overture for Strings in G minor (TWV 55:g2) seems to fit the bill well. Here it’s performed by Collegium Instrumentale Brugense, Patrick Peire conducting.

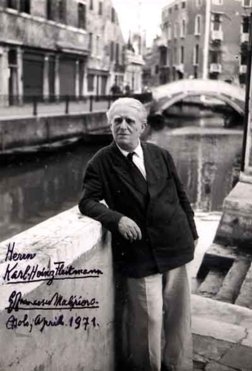

We’ve never written about the 20th century Italian composer, Gian Francesco Malipiero. Malipiero was born on March 18th of 1882 in Venice. His grandfather was an opera composer, his father – a pianist and conductor. Malipiero’s childhood was troubled. His parents divorced, and he spent several years with his father, traveling to Trieste, Berlin and Vienna, where he attended the conservatory. At the age of 17 he left his father and returned to Venice, to his mother’s home. He immersed himself in the newly discovered music of Frescobaldi and Monteverdi; he later considered it an important part of his musical education. In 1913 he went to Paris, where, in addition to all the requisite Frenchmen, he met Alfredo Casella, who became his friend for life. It was Casella who recommended Malipiero attend the premiere of The Rite of Spring; Stravinsky’s music made a big impression on Malipiero. He moved to Rome in 1917, when in the course of WWI, Austrian forces threatened Venice. There he continued his collaboration with Casella, first at the Società Italiana di Musica Moderna, then, in 1923, when they founded the Corporazione delle Nuove Musiche. Reorganization of Italian music was one of Mussilini’s favorite projects, and for a while Malipiero won his favor: he had at least three personal audiences with the dictator. This all ended in 1934, when Malipiero’s opera La favola del figlio cambiato was condemned by the official press. Malipiero tried to get back on Mussolini’s good side and dedicated his next opera, Giulio Cesare, to him, but that didn’t help: Malipiero’s request for an audience was rejected. In 1922 Malipiero bought a house in Asolo, a pretty hilltop town not far from Venice, and lived there for the rest of his life. In 1940 he became a professor at the Venice Liceo Musicale (Conservatory). One of his students there was Luigi Nono. It was through Malipiero that Nono met Bruno Maderna. In addition to teaching, Malipiero edited the complete works of Claudio Monteverdi. He died on August 1st of 1973.

and he spent several years with his father, traveling to Trieste, Berlin and Vienna, where he attended the conservatory. At the age of 17 he left his father and returned to Venice, to his mother’s home. He immersed himself in the newly discovered music of Frescobaldi and Monteverdi; he later considered it an important part of his musical education. In 1913 he went to Paris, where, in addition to all the requisite Frenchmen, he met Alfredo Casella, who became his friend for life. It was Casella who recommended Malipiero attend the premiere of The Rite of Spring; Stravinsky’s music made a big impression on Malipiero. He moved to Rome in 1917, when in the course of WWI, Austrian forces threatened Venice. There he continued his collaboration with Casella, first at the Società Italiana di Musica Moderna, then, in 1923, when they founded the Corporazione delle Nuove Musiche. Reorganization of Italian music was one of Mussilini’s favorite projects, and for a while Malipiero won his favor: he had at least three personal audiences with the dictator. This all ended in 1934, when Malipiero’s opera La favola del figlio cambiato was condemned by the official press. Malipiero tried to get back on Mussolini’s good side and dedicated his next opera, Giulio Cesare, to him, but that didn’t help: Malipiero’s request for an audience was rejected. In 1922 Malipiero bought a house in Asolo, a pretty hilltop town not far from Venice, and lived there for the rest of his life. In 1940 he became a professor at the Venice Liceo Musicale (Conservatory). One of his students there was Luigi Nono. It was through Malipiero that Nono met Bruno Maderna. In addition to teaching, Malipiero edited the complete works of Claudio Monteverdi. He died on August 1st of 1973.

Here’s Malipiero’s Quartet no.1 Rispetti e strambotti, from 1920. It’s performed by the Orpheus String Quartet.Permalink

March 5, 2018. From Gesualdo to Barber. This is another abundant week: Carlo Gesualdo, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, Josef Mysliveček, Pablo de Sarasate, Maurice RavelHeitor Villa-Lobos, Arthur Honegger and Samuel Barber all were born between March 5th and March 10th. Plus, Dame Kiri Te Kanawa, the wonderful soprano from New Zealand, was also born this week, on March 6th of 1944. Of this group, Ravel remains the most popular: by some counts, he is one of the most popular (not to be confused with the greatest) classical composers of all time. While it’s impossible not to love Ravel, our personal favorite is Gesualdo, Prince of Genosa, and not because of the incredible life story of this melancholic murderer and composer of genius, which was portrayed by dozens of poets and writers, from Torquato Tasso to Anatole France. Gesualdo appeals on a purely musical level; he’s one of the most interesting composers of the late Renaissance. The astonishing chromaticism of his madrigals sounds fresh even today. Listen, for example, to Moro, lasso, al mio duolo as performed by the Diller Consort.

A brief note on Mysliveček’s relations with the Mozarts. He met Leopold and Wolfgang in Bologna in 1770 (Wolfgang was 14, and was on one of the trips Leopold organized to demonstrate his brilliant virtuosity as a harpsichordist). Mysliveček became good friends with both, and Wolfgang was especially taken with the Czech’s “fire, spirit and life,” as he put it in one of his letters. The friendship lasted for eight years and fell apart when Mysliveček couldn’t deliver on a promise to arrange a commission for Mozart from the Teatro San Carlo. Mysliveček influenced some of Mozart’s early compositions, for example his opera Mitridate, re di Ponto.Permalink

February 16, 2018. Another rich week. Chopin, Rossini, Smetana, Vivaldi – way too much for one week. Fortunately, last year we wrote about the first three, so we’ll just play a bit of Chopin’s music. Just two days ago we came across a live video of a Chopin recital given by the Georgian pianist Eliso Virsaladze. Ms. Virsaladze, who is 75 years old, started with the Polonaise-fantaisie op. 61, then played the massive Piano sonata no. 3. In the second half it was several nocturnes, valses and one Etude, no. 3, op. 10. She even played an encore, a Mazurka, Op. 30, no. 4. It was a long program even for a young pianist and the performance, if maybe not technical perfect (she clearly got tired by the end), was very satisfying. Eliso’s first teacher was her grandmother, Anastasia Virsaladze, a pupil of the famous Anna Yesipova (Yesipova, a very influential teacher at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, also taught Sergei Prokofiev and Maria Yudina; she was the second wife of Theodor Leschetizky, who helped Anton Rubinstein in founding the St. Petersburg Conservatory). In 1966 Eliso moved to Moscow to study with Heinrich Neuhaus and Yakov Zak. Eliso took the third prize in the Second Tchaikovsky competition (1962) and won the Schumann competition in Zwickau four years later. Schumann was one of her favorite composers; at the time, Sviatoslav Richter said that she was the best contemporary interpreter of Schumann’s music. She also played a lot of Chopin. Here are 12 Etudes op. 10 in a studio recording made in 1974. We first wanted to select one etude but decided that playing all of them together is so much better – and it’s just 29 minutes of great music. Antonio Vivaldi was born on March 4th of 1678, so this week marks his 340th birthday anniversary. He’s famous for the hugely overplayed and overused Four Seasons, but, in addition to a lot of second-rate pieces (he wrote an enormous number of concertos, more than 500 of them, mostly for string instruments, and 46 operas) he also wrote some wonderful but rarely performed music. His operas, for example, are just being “discovered,” many of them thanks to the wonderful Cecilia Bartoli. Clearly, Bach thought very highly of Vivaldi, as he took 10 of his violin concertos and transcribed them to either the harpsichord or the organ. Vivaldi seems to have created a unique musical genre he called Introduzioni, or introductory motets, which were intended to be performed before a larger choral composition, such as Gloria or Miserere. Vivaldi wrote eight such introduzioni. One of them is called Filiae Maestae Jerusalem (Mournful daughters of Jerusalem); it was intended to precede a Miserere, now lost. This particular introduzioni consists of three movements: a recitative (listening to it, one is reminded of recitatives in Bach’s Passions), a beautiful Aria, followed by another, shorter recitative. Here it is, performed by the French countertenor Gérard Lesne and the ensemble he founded, Il Seminario musicale.Permalink

started with the Polonaise-fantaisie op. 61, then played the massive Piano sonata no. 3. In the second half it was several nocturnes, valses and one Etude, no. 3, op. 10. She even played an encore, a Mazurka, Op. 30, no. 4. It was a long program even for a young pianist and the performance, if maybe not technical perfect (she clearly got tired by the end), was very satisfying. Eliso’s first teacher was her grandmother, Anastasia Virsaladze, a pupil of the famous Anna Yesipova (Yesipova, a very influential teacher at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, also taught Sergei Prokofiev and Maria Yudina; she was the second wife of Theodor Leschetizky, who helped Anton Rubinstein in founding the St. Petersburg Conservatory). In 1966 Eliso moved to Moscow to study with Heinrich Neuhaus and Yakov Zak. Eliso took the third prize in the Second Tchaikovsky competition (1962) and won the Schumann competition in Zwickau four years later. Schumann was one of her favorite composers; at the time, Sviatoslav Richter said that she was the best contemporary interpreter of Schumann’s music. She also played a lot of Chopin. Here are 12 Etudes op. 10 in a studio recording made in 1974. We first wanted to select one etude but decided that playing all of them together is so much better – and it’s just 29 minutes of great music. Antonio Vivaldi was born on March 4th of 1678, so this week marks his 340th birthday anniversary. He’s famous for the hugely overplayed and overused Four Seasons, but, in addition to a lot of second-rate pieces (he wrote an enormous number of concertos, more than 500 of them, mostly for string instruments, and 46 operas) he also wrote some wonderful but rarely performed music. His operas, for example, are just being “discovered,” many of them thanks to the wonderful Cecilia Bartoli. Clearly, Bach thought very highly of Vivaldi, as he took 10 of his violin concertos and transcribed them to either the harpsichord or the organ. Vivaldi seems to have created a unique musical genre he called Introduzioni, or introductory motets, which were intended to be performed before a larger choral composition, such as Gloria or Miserere. Vivaldi wrote eight such introduzioni. One of them is called Filiae Maestae Jerusalem (Mournful daughters of Jerusalem); it was intended to precede a Miserere, now lost. This particular introduzioni consists of three movements: a recitative (listening to it, one is reminded of recitatives in Bach’s Passions), a beautiful Aria, followed by another, shorter recitative. Here it is, performed by the French countertenor Gérard Lesne and the ensemble he founded, Il Seminario musicale.Permalink

February 19, 2018. From Blow to Kurtág. We have a wonderful group of musicians to celebrate this week. Luigi Boccherini was born on this day in 1743 in Lucca. He studied in Rome, at the age of 14 he moved to Vienna where he played the cello at the Burgtheater, and four years later, in 1770 he moved to Madrid. There he was employed by the younger brother of the King of Spain, Infante Luis Antonio. His official title was compositore e virtuoso di camera. He lived in Spain for the rest of his life, even while holding an appointment with the Crown Prince of Prussia. Boccherini died in Madrid on May 28th of 1805. He wrote more than 100 quartets – Minuet from String Quintet in E Major, Op.11 No. 5 is probably his most famous piece of music. Here’s another of his string quartets, “La Tiranna,” in G major, Op. 44, no. 4. It’s performed by the Ensemble 415.

Luis Antonio. His official title was compositore e virtuoso di camera. He lived in Spain for the rest of his life, even while holding an appointment with the Crown Prince of Prussia. Boccherini died in Madrid on May 28th of 1805. He wrote more than 100 quartets – Minuet from String Quintet in E Major, Op.11 No. 5 is probably his most famous piece of music. Here’s another of his string quartets, “La Tiranna,” in G major, Op. 44, no. 4. It’s performed by the Ensemble 415.

Also born today but almost two centuries later, in 1926, was one of the most influential composers of the second part of the 20th century, György Kurtág. A Hungarian, he was born in the town of Lugoj, part of the Austria-Hungary that reverted to Romania after the Great War. He studied music in Timișoara (also formerly a Hungarian city) and in 1946 moved to Budapest. He became friends with another young composer, György Ligeti. In 1957 Kurtág went to Paris where he studied with Olivier Messiaen and Darius Milhaud. After the limitations of the socialist Hungary, Paris offered Kurtág access to all the modern music he wanted to hear. He listened to the Viennese, especially Webern; other influences were Stravinsky and Bartók. Had he stayed in Paris, his life would’ve been very different, but he chose to return to Hungary. There he earned money as an accompanist and voice coach. He didn’t receive international recognition as a composer till the 1980s. He could afford to retire from teaching only in 1986, and left Hungary in 1993. Since then, he has worked in Berlin, Paris, Vienna and other cities. He now lives in Bordeaux. Kurtág’s music is difficult, but as we’ve said many times when talking about contemporary composers, it’s usually worth the effort. Here’s a piece dedicated to his friend, Pierre Boulez, Petite musique solennelle en hommage à Pierre Boulez. The Lucerne Festival Academy Orchestra is conducted by Matthias Pintscher.

The English Baroque composer John Blow, the oldest in our group, was born on February 23rd of 1649. At the age of 19 he was appointed the organist at the Westminster Abbey and later assumed the same position at the Chapel Royal. In 1664 he was made Master of the Children of the Chapel. In this position he taught a generation of future composers, Jeremiah Clarke among them. Daniel Purcell, the younger brother of Henry Purcell, was also his student. Blow was very fond of Henry and even resigned as theorganist at the Westminster Abbey to allow Purcell to take his place. The two composers were good friends, and when Henry Purcell died at the age of 36 in 1965, Blow wrote an Ode on his death. Blow’s favorite musical genre was the Anthem, a form similar to a catholic motet, and usually written to a specific text. Here’s the coronation anthem for King James II, God Spake Sometimes in Visions, which Blow composed in 1695. The Choir of King's College, Cambridge and Academy of St. Martin in the Fields are conducted by David Willcocks.

The greatest in the group, George Frideric Handel, was also born this week, on February 23rd of 1685. A German, he visited London in 1710, staged his new opera, Rinaldo, to great success and moved to England permanently in 1712 to become England’s national composer. We’ve celebrated him many a time and will do so again in the future. And speaking of opera, Enrico Caruso, probably the greatest tenor of all time, was also born this week, on February 25th of 1873.Permalink