Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

January 1, 2018. Happy New Year! Best wishes to all our listeners in 2018 and lots of good music! While we cannot think of any classical composition written specifically to celebrate theNew Year, its arrival is clearly associated with fireworks, and what could be better fireworks music than George Frideric Handel’s Music for the Royal Fireworks? The occasion for which Handel composed his famous suite was quite different (the end of the War of the Austrian Succession) but we don’t mind. Herer is it, gloriously performed by the Academy of St. Martin in the Field under the direction of Neville Marriner.

music! While we cannot think of any classical composition written specifically to celebrate theNew Year, its arrival is clearly associated with fireworks, and what could be better fireworks music than George Frideric Handel’s Music for the Royal Fireworks? The occasion for which Handel composed his famous suite was quite different (the end of the War of the Austrian Succession) but we don’t mind. Herer is it, gloriously performed by the Academy of St. Martin in the Field under the direction of Neville Marriner.

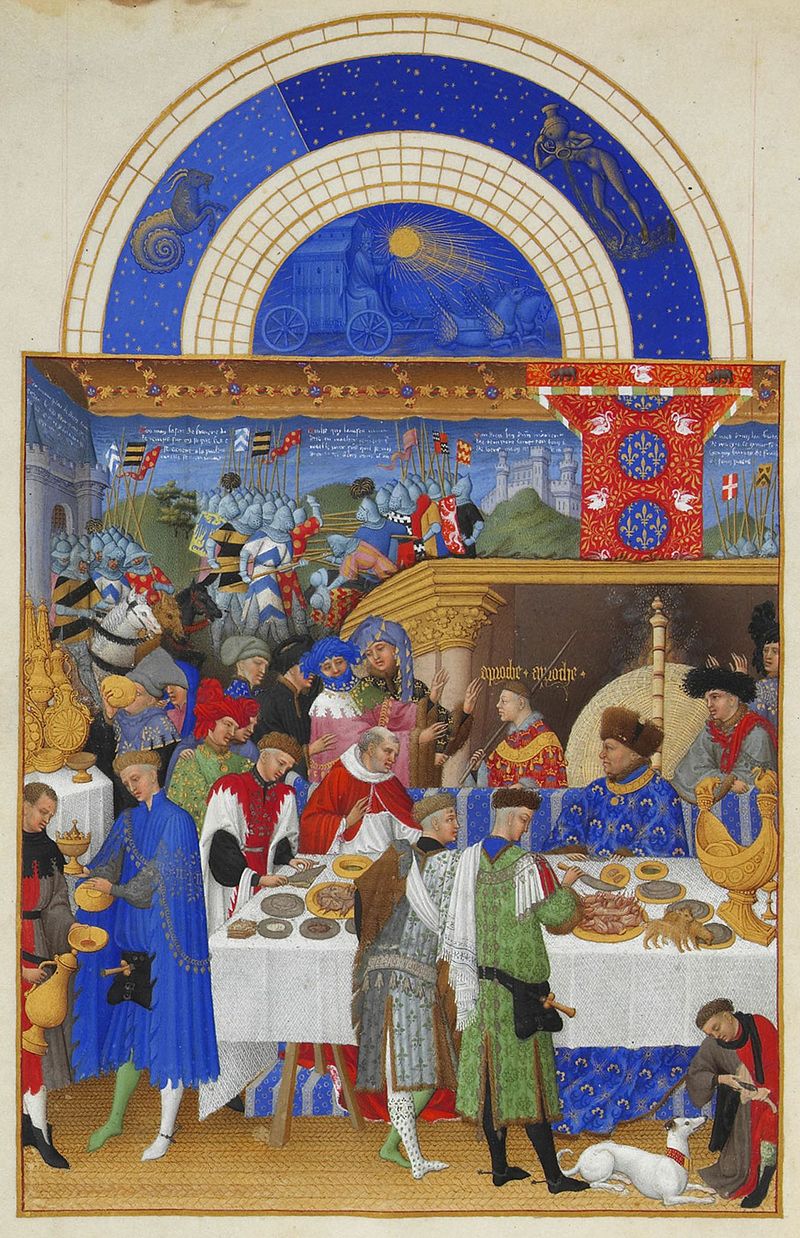

The picture to the left is January, from the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, an illuminated manuscript created by the Limbourgh Brothers at the beginning of the 15th century. The members of the Duke’s household are exchanging New Years’ gifts.Permalink

December 25, 2017. Merry Christmas! As we’ve done in the past several years, we celebrate this wonderful holiday by playing sections from Johann Sebastian Bach’s masterpiece, the Christmas Oratorio. Last year we played the complete Part II, so now we’ll turn to Part III. The Oratorio was written in 1734; in it Bach reused some of the music from Cantatas BWV 213, 214 and 215, which he wrote during the previous year. Thus, the Christmas Oratorio opens with the chorus Herrscher des Himmels, erhöre das Lallen (Ruler of Heaven, hear the sound of laughter), which is taken directly from the chorus Blühet, ihr Linden in Sachsen, wie Zedern! (Bloom, you linden trees in Saxony, like cedars!) in the Cantata BWV 214. Nonetheless, there’s so much new music that the Oratorio clearly could be considered an independent piece of music. The theme of the third part of the Oratorio is Adoration of the Shepherds. As usual, it’s the Evangelist who tells the story: the angels visit the shepherds to reveal to them that a heavenly event has taken place in Bethlehem; the shepherds then embark on a journey; in Bethlehem, they find Mary, Joseph and the Child lying in the manger; they recognize the Child as the one they were told about; they spread the word about the Child: people wonder, only Mary understands the real meaning of it all; the shepherds depart, glorifying and praising the Lord. The Third part of the Oratorio was premiered on December 27th of 1734 at the Leipzig’s St. Nicholas church. We’ll hear it in the performance by the English Baroque Soloists under the direction of John Eliot Gardiner.Permalink

turn to Part III. The Oratorio was written in 1734; in it Bach reused some of the music from Cantatas BWV 213, 214 and 215, which he wrote during the previous year. Thus, the Christmas Oratorio opens with the chorus Herrscher des Himmels, erhöre das Lallen (Ruler of Heaven, hear the sound of laughter), which is taken directly from the chorus Blühet, ihr Linden in Sachsen, wie Zedern! (Bloom, you linden trees in Saxony, like cedars!) in the Cantata BWV 214. Nonetheless, there’s so much new music that the Oratorio clearly could be considered an independent piece of music. The theme of the third part of the Oratorio is Adoration of the Shepherds. As usual, it’s the Evangelist who tells the story: the angels visit the shepherds to reveal to them that a heavenly event has taken place in Bethlehem; the shepherds then embark on a journey; in Bethlehem, they find Mary, Joseph and the Child lying in the manger; they recognize the Child as the one they were told about; they spread the word about the Child: people wonder, only Mary understands the real meaning of it all; the shepherds depart, glorifying and praising the Lord. The Third part of the Oratorio was premiered on December 27th of 1734 at the Leipzig’s St. Nicholas church. We’ll hear it in the performance by the English Baroque Soloists under the direction of John Eliot Gardiner.Permalink

The great Flemish composer Orlando di Lasso (or Orlande di Lassus, as his name is sometimes spelled) was born around 1532 in Mons, county of Hainaut in what is now Belgium. At the age of twelve he followed Ferrante Gonzaga to Mantua, then spent some time in Milan and Naples before settling in Rome. In 1556, already famous as a composer, he was invited to Munich by Albrecht V, Duke of Bavaria, who, eager to compete with Italian courts, was hiring musicians from different countries. Orlando stayed in the employ of Dukes for the rest of his life. Soon after his arrival in Bavaria, Orlando presented the Duke Albrecht with a set of 12 motets, which he titled Prophetiae Sibyllarum ("Sibylline Prophecies"). The author of the texts is unknown, but all of the “prophecies” foretell the coming of Christ. Here are two of the motets, Sibylla Europæa and Sibylla Erythræa, both beautifully performed by the ensemble De Labyrintho, Walter Testolin conducting.

The great Flemish composer Orlando di Lasso (or Orlande di Lassus, as his name is sometimes spelled) was born around 1532 in Mons, county of Hainaut in what is now Belgium. At the age of twelve he followed Ferrante Gonzaga to Mantua, then spent some time in Milan and Naples before settling in Rome. In 1556, already famous as a composer, he was invited to Munich by Albrecht V, Duke of Bavaria, who, eager to compete with Italian courts, was hiring musicians from different countries. Orlando stayed in the employ of Dukes for the rest of his life. Soon after his arrival in Bavaria, Orlando presented the Duke Albrecht with a set of 12 motets, which he titled Prophetiae Sibyllarum ("Sibylline Prophecies"). The author of the texts is unknown, but all of the “prophecies” foretell the coming of Christ. Here are two of the motets, Sibylla Europæa and Sibylla Erythræa, both beautifully performed by the ensemble De Labyrintho, Walter Testolin conducting.

December 18, 2017. Christmas is coming soon, and this gives us a chance to celebrate several Renaissance composers. We usually look for special events to mention them throughout the year, since there are no dates associated with their birthday. What could be a better occasion than Christmas, as all of them wrote church music, and much of it music for Christmas services.

One of the key texts and corresponding chants of the Catholic Christmas liturgy is O Magnum Mysterium (O great mystery), which is sung on Christmas Matins. Many Renaissance composers wrote motets on this text, one of them Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, the quintessential polyphonist of the Hight Renaissance. Palestrina was one of the few Italians working in Rome: most of the famous composers of that time were either Flemish or Spanish (that would change in just one generation and Italians would reign supreme for years to come). Palestrina was born around 1525 in the town of the same name. In 1551 Pope Julius III appointed him maestro di cappella at Cappella Giulia, one of the two key choirs at the Vatican, another being the Sistine Chapel choir). From that point on Palestrina moved from one important position to another. O Magnum Mysterium, Palestrina’s six-voice motet, was published in 1569. It’s sung here by the King's College Choir, Cambridge, Sir Philip Ledge conducting.

Tomás Luis de Victoria also wrote an O Magnum Mysterium motet. Victoria, a Spaniard, is often considered one of the three great High Renaissance composers, together with Palestrina and Lasso. He was born in a small town of Sanchidrián in the province of Ávila in 1548. He went to Rome in 1565 and may have studied with Palestrina. His sublime Mysterium can be heard here, in the performance by the Oxford Camerata under the direction of Jeremy Summerly.

We want to mention another rendition of O Magnum Mysterium, this one by a Venetian, Giovanni Gabrieli. Gabrieli, born around 1554 in Venice, and in his twenties, went to Munich to study with Lasso and stayed there for some years. Here’s his version of O Magnum Mysterium, performed by The Choir of King's College and The Philip Jones Brass Ensemble.

The Adoration of the Kings (1510-1515), above, was painted by Jan Gossaert, who, like Orlando di Lasso, was Flemish and also born in the French-speaking county of Hinaut.Permalink

December 11, 2017. Beethoven. Whatever deity was distributing musical birthdays throughout the year did a very poor job. There are meager weeks, and then there are periods like this one, in the middle of December: we’ve already missed the anniversaries of Jean Sibelius, Cesar Franck and Olivier Messiaen, all born during the last several days (and these are the foremost composers, there are more), while this week three more big ones are coming: that of Hector Berlioz, who was born on December 11th of 1803, Elliott Carter, the American modernist, born on the same day in 1908, and the talented Hungarian composer ZóltanKodaly, whose birthday is December 16th of 1882. We’ll skip all of them until a later date. All of it because December 16th is the birthday of Ludwig van Beethoven and that we cannot miss. Some years ago, we started a survey of Beethoven’s life through his music, pretty much arbitrarily picking his piano sonatas and symphonies, even though we may have as well followed the development of his genius though his quartets or piano trios – and we still might. For the time being, though, we’ll return to his piano sonatas. The last one we disucssed was the Sonata no. 7, op. 10, no. 3, written in 1798, when Beethoven was 27 years old. The next sonata, the famous no. 8, op. 13, known as Pathétique, was written the same year (the title Pathétique was given by the publisher, not the composer himself, but Beethoven liked it and that’s what the sonata was called ever since). Up to then, Beethoven was better known as a pianist rather than a composer (Václav Tomášek, a Czech composer and music teacher, who also heard Mozart, the supreme virtuoso of his time, play, considered Beethoven the greatest performer of all time). Beethoven’s predecessors, Haydn and Mozart, each wrote many wonderful piano sonatas, but Beethoven’s no. 8 was clearly different. Even though written in a traditional classical sonata form and clearly inspired by Mozart’s great piano sonata K. 457, Beethoven’s use of the themes and dynamics, the juxtaposition of different sections, his sense of the dramatic were all absolutely original, and recognizably Beethovenian. The sonata was dedicated to Beethoven’s friend and benefactor Prince Karl von Lichnowsky, who some years earlier played the same role for Mozart. It became immediately popular, establishing Beethoven as a leading composer. Here it is, in a 1959 recording made by the great Soviet pianist Sviatoslav Richter.

more), while this week three more big ones are coming: that of Hector Berlioz, who was born on December 11th of 1803, Elliott Carter, the American modernist, born on the same day in 1908, and the talented Hungarian composer ZóltanKodaly, whose birthday is December 16th of 1882. We’ll skip all of them until a later date. All of it because December 16th is the birthday of Ludwig van Beethoven and that we cannot miss. Some years ago, we started a survey of Beethoven’s life through his music, pretty much arbitrarily picking his piano sonatas and symphonies, even though we may have as well followed the development of his genius though his quartets or piano trios – and we still might. For the time being, though, we’ll return to his piano sonatas. The last one we disucssed was the Sonata no. 7, op. 10, no. 3, written in 1798, when Beethoven was 27 years old. The next sonata, the famous no. 8, op. 13, known as Pathétique, was written the same year (the title Pathétique was given by the publisher, not the composer himself, but Beethoven liked it and that’s what the sonata was called ever since). Up to then, Beethoven was better known as a pianist rather than a composer (Václav Tomášek, a Czech composer and music teacher, who also heard Mozart, the supreme virtuoso of his time, play, considered Beethoven the greatest performer of all time). Beethoven’s predecessors, Haydn and Mozart, each wrote many wonderful piano sonatas, but Beethoven’s no. 8 was clearly different. Even though written in a traditional classical sonata form and clearly inspired by Mozart’s great piano sonata K. 457, Beethoven’s use of the themes and dynamics, the juxtaposition of different sections, his sense of the dramatic were all absolutely original, and recognizably Beethovenian. The sonata was dedicated to Beethoven’s friend and benefactor Prince Karl von Lichnowsky, who some years earlier played the same role for Mozart. It became immediately popular, establishing Beethoven as a leading composer. Here it is, in a 1959 recording made by the great Soviet pianist Sviatoslav Richter.

The next sonata, no. 9 op. 14, no. 1, was written in the same 1798. The description often attached to this sonata is “modest.” And indeed, it doesn’t have the dramatic developments of its predecessor, it’s themes are not as expansive. Still, it’s recognizably Beethoven, couldn’t be mistaken for anything else. In 1801 Beethoven arranged the sonata for a quartet. It doesn’t have a number, 34, from the Hess catalogue. We’ll hear the original piano version here: the pianist Richard Goode is performing Beethoven’s Sonata no. 9 in E Major.

The second composition in op. 14, also written in 1798, is Sonata no. 10. Like the previous sonata, it’s dedicated to Baroness Josefa von Braun, at the time one of Beethoven’s patrons (her husband, Baron Peter von Braun, an industrialist, managed the Viennese court theaters). This sonata, like the no. 9, is not very ambitious, it could rather be called lyrical and exquisite – descriptions not often applied to Beethoven’s sonatas. Also, one can hear Haydn, still an influence. Here it is performed by the American pianist Stephen Kovacevich.Permalink

December 4, 2017. Three opera composers. The last couple of weeks we’ve dedicated our entries to single composers, first Penderecki and then Hindemith. In doing so, we missed several notable anniversaries, so we’ll try to catch up with them this week. Jean-Baptiste Lully, a miller’s son, was born on November 28th of 1632 in Florence. He was 14 when chevalier de Guise, who was visiting Italy at the time, noticed him there during Mardi Gras and brought him to France – not for his musical talents, but so that his niece, la Grande Mademoiselle, could talk to somebody in Italian. From these unusual beginnings, Lully developed into one of the greatest French composers of all time and the founder of the French opera. We’ve written about him extensively (for example, here or here), so we’ll just play some of his music. Lully composed Persée on the libretto of his frequent collaborator, Philippe Quinault. in 1682. Lully called Persée “tragédie lyrique” – opera genre he invented about 10 years earlier. We’ll hear the short Ouverture here (Christophe Rousset conducts the ensemble Les Talens Lyriques) and an excerpt from Act II (here). Cyril Auvity is Persée. Marie Lenormand – Andromède in an Opera Atelier production.

to France – not for his musical talents, but so that his niece, la Grande Mademoiselle, could talk to somebody in Italian. From these unusual beginnings, Lully developed into one of the greatest French composers of all time and the founder of the French opera. We’ve written about him extensively (for example, here or here), so we’ll just play some of his music. Lully composed Persée on the libretto of his frequent collaborator, Philippe Quinault. in 1682. Lully called Persée “tragédie lyrique” – opera genre he invented about 10 years earlier. We’ll hear the short Ouverture here (Christophe Rousset conducts the ensemble Les Talens Lyriques) and an excerpt from Act II (here). Cyril Auvity is Persée. Marie Lenormand – Andromède in an Opera Atelier production.

Lully wasn’t the only opera composer born around this time: two more Italians were, and they were “real” Italians, as Lully took French citizenship in 1661. Gaetano Donizetti’s birthday is November 29th of 1797. Donizetti came from the city of Bergamo, its beautiful older section called Upper City, Città Alta, famous for its architecture and musical tradition. Donizetti, together with Rossini and the younger Bellini, was one of the master composers of bel canto. Donizetti, who lived just 50 years (he died insane of syphilis), wrote almost 70 operas, but only few of them belong to the standard repertory these days: his masterpiece, Lucia di Lammermoor, Anna Bolena, L'elisir d'amore, Roberto Devereux, Maria Stuarta, and two comic operas, L'elisir d'amore and Don Pasquale. Here’s the Judgement Scene, the finale of Act I from Anna Bolena. Maria Callas, the tenor Gianni Raimoni and the bass Nicola Rossi-Lemeni in an exceptional live recording made exactly 60 years ago, in 1957 in La Scala. Gianandrea Gavazzeni is conducting the La Scala orchestra.

Another opera composer is Pietro Mascagni, who was born on December 7th of 1863. Mascagni wrote 15 operas, but is famous for just one, his very first, the marvelous Cavalleria Rusticana. If Donizetti was one of the creators of the Bel canto style, Mascagni, together with another one-opera marvel, Ruggero Leoncavallo, created the style called verismo, an Italian term that could be translated as realism, or maybe naturalism: the subjects of the verismo operas are down to earth, unheroic, like seamstresses and poets in Puccini’s La Boheme. Cavalleria Rusticana was premiered in 1890 (it’s interesting that Verdi was still to complete his last opera, Falstaff). There are more recordings of Cavalleria than practically of any other opera. There are even recordings conducted by Mascagni himself (hard to imagine, but Mascagni died on August 2nd of 1945; by then, Schoenberg was evolving his 12-tone system; Stravinsky was past his neo-classical period, and Olivier Messiaen had just written Vingt regards sur l'enfant-Jésus). Cavalleria is full of wonderful music; one of the best-known arias is Mamma, quel vino è generoso. Here it is in the 1957 recording by Franco Corelli. Arturo Basile conducts Orchestra Sinfonica di Torino della RAI.

We’ve written about three composers, but there are several more we’d like to note. Among them: Padre Antonio Soler, Jean Sibelius, Bohuslav Martinu, Joaquin Turina, a very interesting Soviet composer of Polish-Jewish descent, Mieczysław (or Moisey, as he was called in the Soviet Union) Weinberg, and Cesar Franck. We’ll write about them later.Permalink

November 27, 2017. Esther Walker on Paul Hindemith. A couple of weeks ago we missed Hindemith’s birthday: the German composer was born on November 16th of 1895. Most music lovers w can acknowledge his talent but many would also admit that Hindemith is not “their” composer, that he’s too distant, dry, cerebral. That’s what the Swiss pianist Esther Walker thought of Hindemith earlier in her career. As she got involved with several of Hindemith’s piano pieces, her attitude changed. Esther put her thoughts on Hidemith’s piano works into a very personal and thought-provoking essay. In it she discusses the rarely-performed Ludus tonalis (we may point to the recordings made by the two Soviet pianists and good friends, Sviatoslav Richter and Anatoly Vedernikov), the Suite “1922” and other pieces; examines the problem of conservative programming, firmly placing the blame on performers (and organizers), rather than composers or listeners; and gives us an insightful overview of Hindemith’s life. Here is an excerpt from the beginning of the essay; you can read the complete piece on Esther’s site. ♫

composer, that he’s too distant, dry, cerebral. That’s what the Swiss pianist Esther Walker thought of Hindemith earlier in her career. As she got involved with several of Hindemith’s piano pieces, her attitude changed. Esther put her thoughts on Hidemith’s piano works into a very personal and thought-provoking essay. In it she discusses the rarely-performed Ludus tonalis (we may point to the recordings made by the two Soviet pianists and good friends, Sviatoslav Richter and Anatoly Vedernikov), the Suite “1922” and other pieces; examines the problem of conservative programming, firmly placing the blame on performers (and organizers), rather than composers or listeners; and gives us an insightful overview of Hindemith’s life. Here is an excerpt from the beginning of the essay; you can read the complete piece on Esther’s site. ♫

On Piano Music of Paul Hindemith.

Like many others before me, I too, in my youth and student days, grew into an unconsciously assumed, hardened and prejudiced (pre)conception of Hindemith. But the very few encounters which I had with this composer as a young pianist – whether it was through occasionally playing one of the Kammermusiks (op. 11) or hearing an orchestral work – forced me each time to cast doubt on this picture which I had of Hindemith. But some years ago, when it happened that I had to study four of Hindemith’s works (the Suite “1922”, the Kammermusik No. 1, The Four Temperaments and the Double Bass Sonata) in a relatively short period of time, I was forced to engage with this music in a much more intensive way than before and was really able to jettison my sometimes-unconscious prejudices. My active interest in Hindemith was aroused.

Of course, there are true Hindemith specialists who devote themselves to this composer and who consequently have a deep access to his output and a profound and unprejudiced knowledge of his life and work.

Since I don’t exactly move in these specialist circles, I believe I can say that, unfortunately even today – especially in Latin countries – Hindemith’s music has the reputation, surely somewhat exaggerated, of being the product of an austere, nonsensical and emotionally-impoverished intellectuality, schoolmasterly and accordingly of little artistic worth.

Even Alfred Brendel, one of the great musical personalities of our time, who is so open, interested and intelligent, and who is able to exert a lasting influence on the next generation, refers to Hindemith in his two books Reflections on Music and Music Taken at his Word in only three passing comments, in which there is no mistaking a rather negative attitude to the composer. In an interview at the end of one of the books Hindemith is quoted in just one sentence, and to quote him so cursorily is usually dangerous, since a little later he would often contradict his pithy, sometimes provocative utterances, or at least qualify them. [Please continue reading here].Permalink